1. Context

Adoption is the voluntary acceptance of a child of other parents as one's child, usually with a legal confirmation. Adoption, whether formal or informal, has always been a method of ensuring the survival of children whose parents are unwilling or unable to care for them (1). An adoptive family can provide a supportive environment for recovering from physical and psychological injuries and reversing some developmental deficits (2). However, adoption can also profoundly affect child development. Adopted people have a higher lifetime prevalence of psychological distress or mental disorders. This higher risk of psychiatric problems in this population may be explained by the conjugation of both genetic and environmental factors (3).

On the other hand, suicide behaviors include the spectrum from a death wish to self-harm and completed suicide (4). The rates of self-injurious acts with an apparent death intention, suicide attempts, and total suicides are often used as the best indicators of mental problems in the population due to the difficulty of quantifying other direct indicators of collective psychological distress (5).

From a genetic perspective, parents of children and adolescents who are given up for adoption more frequently meet the criteria for mental disorders, substance use and dependence, and antisocial personality disorders, which means that their children are more vulnerable to meet the criteria for mental disorders (6). Instead, from an environmental perspective, the adoption situation can represent a chronic stressor, and per se produce a negative impact on psychological development (7). This chronic stressor can be called adoption stigma-discrimination, not only of the person in an adoption situation but also of the whole family group (8).

The institutions in charge of processing adoptions in most countries try to ensure that adoptive parents have the best possible characteristics and conditions, with the probable intention of not re-victimizing or causing more significant harm to people who are already in vulnerable circumstances. This situation often delays the adoption processes and causes the probability of more considerable emotional damage to occur in minors, which, in turn, can increase the risk of suicide behavior (9). Contrariwise, it should not be forgotten that being in a condition of adoption makes a difference that favors discriminatory treatment by different members of society and creates an adverse environment for the adopted child (10). Something similar to the theory of disability happens here, in the sense that it is the society that constructs the discriminatory condition and the subsequent repercussions on the mental health of adopted children (10, 11). In summary, adoptees often present psychiatric morbidity and social disadvantage, and these variables are independent risk factors for suicide attempts among young people (3, 4).

Some systematic reviews or meta-analyses have been carried out to summarize the association between the adoption situation and outcomes in intelligence quotient (9, 10), cognitive functioning (12, 13), social functioning (14), school performance (15, 16), behavioral problems (14-17), psychological adjustment (13-15, 18), and mental health (14, 15, 18-21). However, no meta-analysis consolidates the information about the specific association between the adoption situation and suicide attempt.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to estimate the association between adoption situation and suicide attempts through the systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies.

3. Methods

A meta-analysis of primary studies was done. The review included only studies that compared the outcome of suicide attempts in adopted and non-adopted adolescents and adults.

3.1. Searching for Relevant Studies

A logical strategy based on specific descriptors in Spanish, English, and Portuguese was used in combination with the Boolean operators (AND, OR). The search was performed on PubMed, Scopus, Virtual Health Library, ProQuest, EBSCOhost, PsycArticles, BioMed Central, and Sage Journal. The search results in the grey literature were omitted. The descriptors were "adoption", "adopt*", "adopted child", "foster child" "youth in adoption*", "suicide*", "case-control study", "case-control", "cohort studies", and "cohort*".

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The authors included articles from January 2000 to December 2018 in English, Portuguese, and Spanish. Searching for meta-analyses solely included papers in Portuguese and Spanish. It also considered case-control and cohort studies on both national and international adoption. We excluded cross-sectional studies and case reports.

3.3. Data Extraction

The titles of the studies were initially examined. Subsequently, two authors independently reviewed the abstracts, and finally, the selection of the articles was completed after reading the methods and results sections. The quality of the studies was evaluated with an instrument for critical appraisal of scientific articles (22). This tool adequately summarized the STROBE criteria for observational studies (23).

3.4. Synthesizing Data and Bias Controlling

Data synthesis was conducted using RevMan 5 (24). When a primary outcome study reported multiple measures at different points in time, the newest measure was taken because of looking for a long-term consequence. The Odds Ratio (OR) and a 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated for case-control studies and the relative risk (RR) and 95% CI for cohort studies.

3.5. Assessment of Heterogeneity

There is a condition for the meta-analysis that the group of trials is sufficiently homogenous in terms of participants and outcomes. The variability among studies is termed heterogeneity, and it can arise from methodological diversity (e.g., age when adopted). Heterogeneity (tau) was evaluated using I2; the values > 50% were classified as elevated. When heterogeneity is low, the fixed-effects model is indicated; by contrast, the random-effects model is preferred if elevated heterogeneity is observed (25).

4. Results

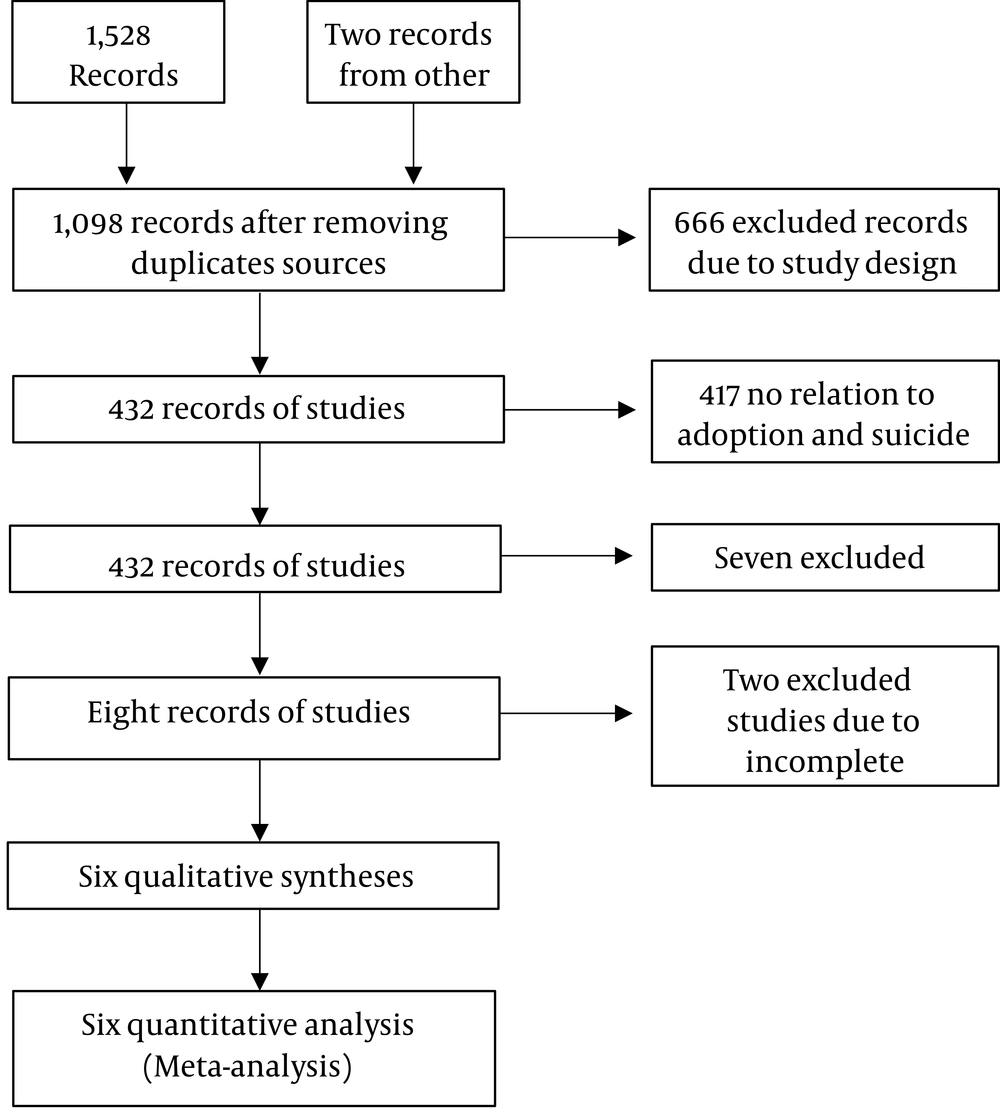

Eight articles met the inclusion criteria. Two papers were excluded due to insufficient information; one allowed the calculation of the association a (3), and the other included the time variable in the analysis without giving details of the number of cases presented (Figure 1) (26).

Of the remaining six studies, three studies used case-control designs (27-29) and the remaining three were cohort studies (30-32). Case-control studies computed 69 suicide attempts in 1,216 adopted people compared to 436 attempts among 20,555 non-adopted people (OR = 2.30, 95% CI 1.24 - 4.28). A random model was used due to the high heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 61%). More details are found in Table 1.

Cohort studies assessed a total of 536 suicide attempts among 36,965 people in adoption compared to 15,112 attempts amidst 3,118,069 non-adopted people (RR = 2.99, 95% CI 2.54 - 3.53). A random model was preferred because of the high heterogeneity (I2 = 73%). More information is seen in Table 2.

5. Discussion

This meta-analysis shows that adopters may have a higher chance of suicide attempts than non-adopters. This observation is consistent with other studies that found that people in adoption had two to three times more risk of total suicide than non-adopted people (33). This finding agrees with other systematic reviews or meta-analyses, which found poorer outcomes for adoptees than persons from the general population on indicators of intelligence quotient, cognitive functioning, social adjustment, school achievement, behavioral troubles, psychological problems, and psychiatric diagnoses (12-21).

The adoption situation is configured as a risk for suicide behaviors because it brings together different factors that increase the possibility of psychological suffering, including behavioral problems, adoption stigma-discrimination, substance use, and depressive disorders in biological parents (1). Besides, the adoption situation should represent a long-term life stressor with physiological and psychological repercussions that can undermine the general health of adopted people (8).

Moreover, the stigma-discrimination process is an additional negative stressor for adoptees, and it can play a determining role in the negative impact on the mental health of adopted children (8). Being outside the line assumed as "normal" is a starting point that places these children in a condition of vulnerability and adds to the initial vulnerability; the difficulty that people have in understanding and assuming differences is known (3). Alternatively, making an analogy from the theories of disability, institutions, and people builds adverse conditions for adopted children (10, 11). Furthermore, this negative differentiation and these limitations are more decisive, which can cause more considerable damage to the mental health of adopted children and, therefore, increase the risk of suicide attempt (4).

To summarize, the adoption situation brings together disadvantaged cultural, socioeconomic, and biological differences that are all related to suicide behaviors. The high prevalence of psychiatric disorders combined with severe psychosocial circumstances plays an essential role in the frequency of suicide attempts among adoptees (1, 3, 4). Suicide prevention programs must consider the adoption background as a crucial variable to control (1, 4).

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

The current meta-analysis suggests a statistically significant relationship between adoption situation and suicide attempts. However, this review has several limitations; it is necessary to interpret the findings with caution since it analyzed observational studies that had more varied populations than randomized clinical trials (34). Also, a small number of investigations were reviewed, and high heterogeneity was observed. Case-control studies were only conducted in the United States and cohort studies exclusively in Sweden. Moreover, the grey literature was excluded (34, 35).

In conclusion, the adoption can increase suicide attempts. It predicts at least two times more cases of suicide attempts among adopted people than in the general population. More investigations are needed to deepen the knowledge on this topic. Furthermore, it is necessary to bear in mind the adoption situation when designing programs for the specific prevention of suicide behaviors.