1. Background

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an infection that attacks the immune system, especially white blood cells, called CD4 cells. HIV destroys these CD4 cells and weakens an individual’s immunity against infections, such as tuberculosis and some cancer types (1).

On the other hand, acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a definition of surveillance based on the symptoms, signs, infections, and cancers associated with immune deficiency resulting from HIV infection (2).

At the end of 2019, the number of people (at all ages) living with HIV (PLHIV) worldwide was estimated to be 38.0 million people [31,600,000 - 44,500,000], 68.7% of whom live in Africa, 10% in South-East Asia, 9.2% in the Americas, 6.6% in Europe, 5.01% in the Western Pacific, and 1.05% in the Eastern Mediterranean (3).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the estimated number of HIV-infected cases in Iran was 59,000 [33 000 - 130 000] in 2019. The infection rate is lower than 1% in the general population of Iran and over 5% in high-risk groups (stage of the concentrated epidemic) (4).

Based on the report of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Iran, by March 20, 2019, a total of 39,545 people have been diagnosed, recorded, and reported, including 82% male and 18% female, and 50% of cases registered are in the age group of 20 - 35 years. The causes of HIV infection among all the cases registered in the country since 1986 are as follows: sharing injecting equipment among injection drug users (IDUs) (60.8%), high-risk sexual behavior (21.6%), and mother-to-child transmission (1.6%), respectively. The transmission route remains unknown in 15.7% of this group. However, the pattern of transmission route and the infection rate of females and males have changed in recent years so that females account for 31% and males for 69% of all cases diagnosed and reported in the first twelve months of this year (2020). In addition, the possible routes of transmission have been reported to be the injecting drug use (31%), high-risk sexual behavior (48.6%), mother-to-child transmission (3%), and unknown (17.4%), and no new infected case has been documented through the blood transfusion (5).

HIV infection affects all aspects of life, including mental, physical, social, and spiritual. It can also cause fear of living with the infection. This infection can cause loss of social, economic, employment, and housing status. Therefore, PLHIV are very vulnerable and need psychological support from their family and community (6, 7). Living with a chronic infection, such as HIV/AIDS, in addition to its physical effects, is associated with numerous psychological problems, such as poverty, social stigma, depression, and social isolation, and those associated with stress and depression (8, 9).

Evidence suggests that effective HIV/AIDS information interventions have the potential to modify people’s manners and decrease the spread of this infection. Nevertheless, one of the main pillars of effective HIV interventions is a thoughtful manner from PLHIV (10, 11).

While some studies are conducted on a social support network, stigma, quality of life, and familial problems among PLHIV in Iran (12-19), more investigations are needed on different aspects of their living experience.

The contributing factors include poor access to medical care, fear, shame because of stigmatization, and lack of social support resulting in the isolation of people who share their status.

2. Objectives

This qualitative study investigated the experiences of PLHIV in Jahrom County, south of Iran.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Study Design

This is a qualitative study based on the facts and perspectives of individuals (15). Qualitative studies are used to gain a rich understanding of a phenomenon as being and are understood and experienced by individuals (20). In this study, qualitative research with a phenomenological descriptive approach was used to examine the individuals’ perception and understanding of HIV infection.

The data were collected through in-depth and semi-structured interviews (face to face). All interviews were recorded, and after the interview, field notes were made.

The length of each interview was 30 to 60 minutes depending on the content of the topic and the conditions of each participant, and different factors, such as time, willingness, endurance, and ability of the individual. Twenty-one participants who were referred to the Jahrom Counseling Center for Behavioral Diseases participated in this study. They were selected via the purposive sampling technique according to theoretical saturation. Saturation has attained widespread acceptance as a methodological principle in qualitative research (21, 22).

The inclusion criteria were HIV-infected males and females being able to communicate and willing to participate in the study. The patients were required to be geographically located inside the area under the coverage of Jahrom Counseling Center for Behavioral Diseases. Patients who were not willing to participate in the study were excluded.

The interviews were conducted in a consulting room with a quiet and private atmosphere at the time the participant felt comfortable. The interviewer was one of the psychologists with more than ten years of experience in the field of counseling with behavioral diseases, who before the study was trained about the objectives of the study. The interview guide questions were based on the purpose of the study and assessed the following issues: how they were infected, how they felt when they were affected, receiving family and social support, the difference in behavior facing an HIV-infected person compared with other patients, and hope for the future.

3.2. Data Analysis

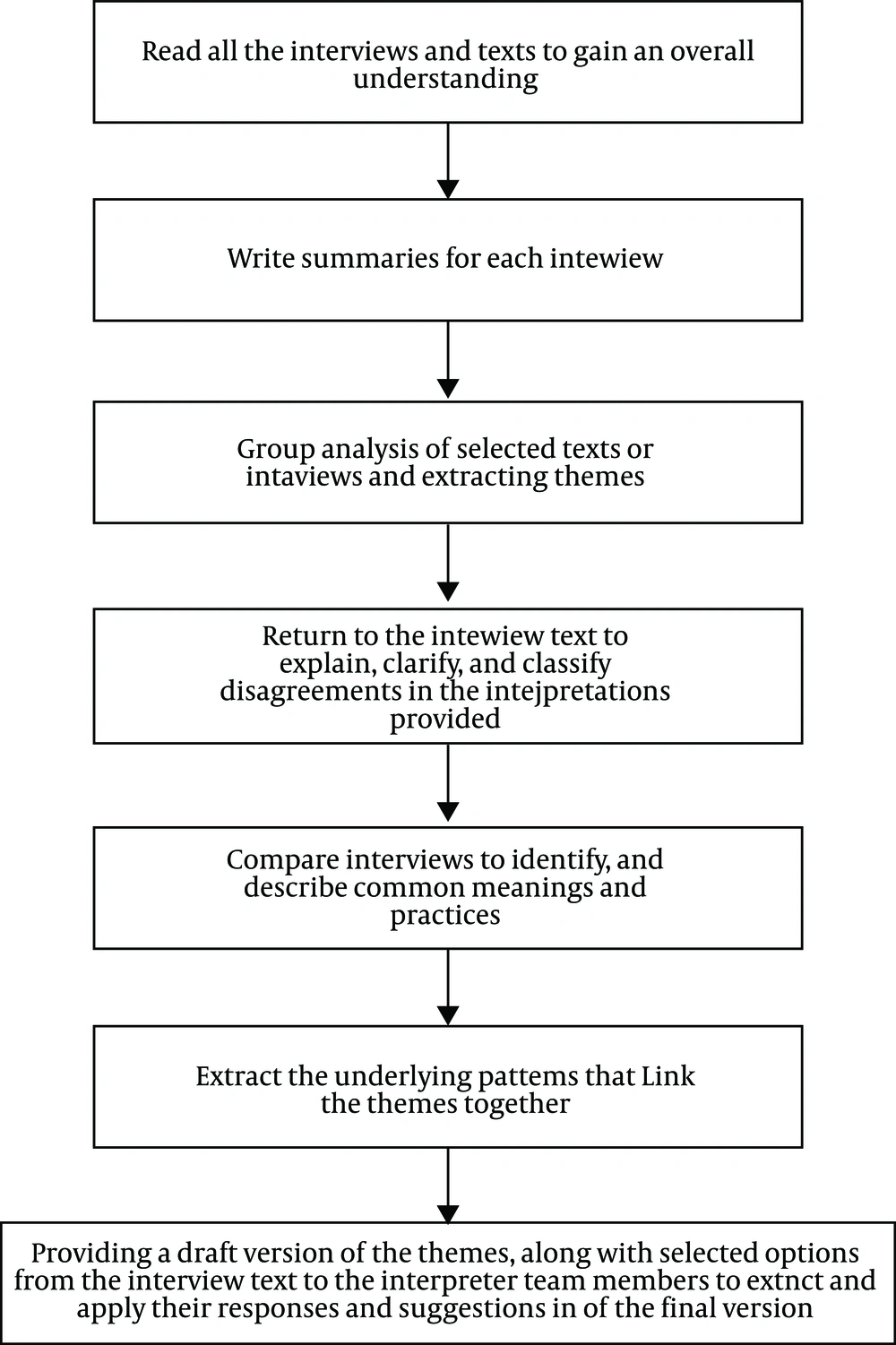

Data were analyzed using the Diekelmann method (23). This is a seven-step process based on Heidegger’s phenomenology with a team nature (Figure 1). To validate the results, the Lincoln and Guba scale (24) was considered, including credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability. To this end, this study focused on long-term conflicts, ongoing observations, expert control of the codes and categories, diverse sampling by age and cultural background, and detailed reporting of details and stages of the study. The three data coders (one principal investigator and two co-investigators) coded the data. Codes and interviews were submitted and approved by qualified experts in the field. Participants were used to validating the interpretation of the data.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

At first, the aims and methods of the research were explained to the participants, and then informed consent forms were completed and signed by them. They were made sure of the complete confidentiality of their given information. The place and time of the interview were determined by the participants. The principles of "no harm" and "confidentiality" were followed. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jahrom University of Medical Sciences (ethics code ID IR.jums.REC.1395.085).

4. Results

A total of 10 (47.62%) males and 11 (52.38%) females with a mean age of 38.81 ± 7.76 years ranging from 28 to 58 years were enrolled (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 10 |

| Female | 11 |

| Educational level | |

| College | 2 |

| Diploma | 4 |

| High school and elementary | 15 |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 11 |

| Single and never married | 9 |

| Divorced | 1 |

The analysis of interview data and notes resulted in the four key themes: emotional and psychological disturbances, stigma, supportive environment and vision, and looking to the future (Table 2).

| Overarching Category | Theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| Lived Experiences | Emotional and psychological disturbances | Fear |

| Depression | ||

| Feeling victimized | ||

| Stigma | The fear of being exposed | |

| False judgment | ||

| Discrimination | ||

| Supportive environment | Family support | |

| Social support | ||

| Vision and looking to the future | Hopelessness about the future | |

| The importance of the children’s future | ||

| Hope for the future and finding a cure |

4.1. Emotional and Psychological Disturbances

One of the themes of the participants’ statements is the emotional and psychological disturbance, which includes three sub-themes of fear, depression, and feeling victimized.

4.1.1. Fear

Most interviewees expressed their fears and worries after detecting their illnesses, most notably the fear of death, the fear of being rejected by others, the fear of the uncertain future awaiting them, and the fear of their children’s future.

When diagnosed with the infection, a 36-year-old single man stated:

“I was very scared, worried about dying, what day I was going, my family was rejected, I failed.”

A 43-year-old single woman said:

“I was worried about my life, and if anyone proposes to live and marry me, I cannot explain to my fiancé the disease, and I have to reject the proposal for marriage. Now I have a suitor, but I can’t tell them I am infected with HIV”.

Five participants (all female) stressed fears and worries about their children and what their fate would be if they die. They were also worried if their children are infected.

“I was very upset. I thought I was going to die, and my son and daughter would be alone”.

“My nerves shattered when I got sick. I’m afraid of dying and worried about my children. I wonder what would happen to my children”.

4.1.2. Depression

In general, PLHIV has physical, psychological, and social problems that are related to each other. When people are diagnosed with the disease, their mental health problems usually increase. The most common psychological feeling among PLHIV is depression.

A married 34-year-old woman said:

“I was so upset and crying all day long. I felt my life was over. The day I found out I was sick and went home, I didn’t talk to anyone. My sister and brother noticed that my behavior changed. But I dodged it and ran away. I wanted to be alone”.

A 28-year-old single woman said:

“I was feeling so sad. I was very angry and crying. I was full of life. I even thought of committing suicide. I felt that my life was over and had no purpose”.

4.1.3. Feeling Victimized

This theme often exists among participating women who were infected through their partner. They consider themselves as the victims of the wrong action of their partners. They call themselves victims because they were victims of the infidelity of a partner who did not inform them about their status.

A 32-year-old woman described her experience as follows:

“I got sick through my husband, who was addicted and infected. I was contacted by the counseling center, and they raised the issue. When I found out that he was infected, I looked at him with an anger. I was tested positive. My nerves shattered. Worst of all, I was pregnant. This bothered me. A baby had to be born sick. He, too, was an innocent victim of my husband”.

A 43-year-old woman stated:

“I got HIV through my husband. My family recommended me to get tested after finding out about my husband’s illness. I never forgive him, and I always curse him. He is to blame. I innocently fell victim to his wrongdoing. In the first year, I found out I divorced him”.

4.2. Stigma

Stigma includes three sub-themes of the fear of being exposed, false judgment, and discrimination.

4.2.1. The Fear of Being Exposed

The most important aspect and the component of social stigma associated with AIDS was to conceal it. This secrecy is the result of fear of prejudice and unfair judgments.

Non-disclosure and secrecy occur at both family and community levels; however, at the family level, the amount of secrecy is lower than in the community because at least one family member is aware of the individual’s illness.

A married 34-year-old woman said:

“I only disclosed my disease to two of my sisters. First, I talked to them about HIV. And after a few days I told them I am diagnosed too”.

A 49-year-old married man said:

“I disclosed my disease to my family regularly. First, I told them that I have blood cancer. Then I got to know the behavioral counseling center. I suggested my wife to run a test, and she found out”.

A 28-year-old single woman said:

“Only my sister knows about my disease. My parents never know about my case. I have no intention of talking to them about my case because they might think that it’s too dangerous”.

4.2.2. False Judgment

A 36-year-old married woman said:

“I’m very upset. If anyone finds out that I have the disease, the first question that anyone may raise is how I was infected. If I replied that I was infected through my husband, they wouldn’t believe it”.

A 31-year-old married man said:

“Anyone who wants to give an example of bad people says, ‘do you have AIDS’? So, I could not behave properly as some people keep away from me, and they did not even shake a hand with me. During new year’s celebration, everyone rubs together. But when they get to me. They did not kiss me and did not shake hands with me. "

4.2.3. Discrimination

In response to the question, how do you think of people’s attitude towards AIDS compared with other diseases?, many interviewees emphasized the discrimination that excludes other people from society.

A 50-year-old single man said:

“Even the nurses at the hospital did not have right knowledge of the disease. I remember that one of the nurses told me to be careful that others do not to get sick. It was surprising that they did not use the same glass that I had used to drink. To me, they were not educated properly, and they had little knowledge”.

A 43-year-old married woman said:

“We were dissatisfied with the staff in the hospital because they misbehaved. Their behavior towards HIV-infected patients is very different from that of other patients. They respect others, and they treat us like a murderer or perhaps worse”.

A married 35-year-old woman said:

“For my parturition when I went to the hospital, the clinical staff treated me very badly. They didn’t even look me in the eyes. If the staff find out that someone has the disease, they would treat him differently. The staff just think of sexual transmission of disease and did bias judgment before taking an action”.

4.3. Supportive Environment

4.3.1. Family Support

Many participants have talked about their illness with their family, and most have been supported by other family members. Therefore, the first source of support that patients received was from their families.

A 42-year-old single man said:

“I told my family with the help of the health center staff. They had no special reaction and behaved normally. As if something positive has happened”.

A 31-year-old married man said:

“My family was present when I received the results of the test. My father, mother, and wife were with me, and they were crying. My mother hugs me and kisses me every day”.

A married 34-year-old woman said:

“My wife did not treat me badly, and she was kind to me. She said you were neither the first nor the last. You also got unintentionally infected.”

A 28-year-old single woman said:

“My sister’s behavior wasn’t too bad. But she still keeps me away. For example, she doesn’t join me at dinner”.

4.3.2. Social Support

Another source of support was from friends and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), but almost all of them preferred not to talk about their problems with friends, and most of the interviewees have used supports from the community and public services.

A 38-year-old married man said:

“I have never disclosed my case to my friends. I think I will continue not to disclose it. My rational is that my friends cannot help me except to bother me with their eye contact. I remember that when I go to the health center, every time I get stressed out as one of my friends won’t even see me”.

A 32-year-old married man said:

“I prefer not to talk to my friends about my case, my hometown is a small city, everybody knows each other, and as soon as this secret is revealed, we are fingerprinted in the city. I have decided not to tell my friends, even if they can help me the best”.

A Single 28-year-old woman said:

“I used community, health, psychological and social services. But I have not referred to other institutions. The staff at the Counseling Center for Behavioral Diseases gave me great hope, helped me to get back into the community. I was very pleased with their support”.s

One patient said:

The counseling staff at the Counseling Center for Behavioral Diseases tried to calm me down so that I could accept my disease, but I was unhappy with the clinical and physician staff”.

4.4. Vision and Looking to the Future

This theme includes three sub-themes of hopelessness for the future, the future importance of children, and hope for the future and finds a cure.

4.4.1. Hopelessness About the Future

A 31-year-old married man said:

“The future is not predictable for me. I don’t know what is going on. Will I survive?”

A 36-year-old married woman said:

“I see no future for which I have a vision. Do we have a life to think about the future?”

4.4.2. The Importance of the Children’s Future

“…I would like to see my son as bridegroom. I am trying to have a good future for them. I hope my illness does not stop my children to develop” …

4.4.3. Hope for the Future and Finding a Cure

A 49-year-old married man said:

“Science is advancing, and we can hope for both a healthy life and an end to the whole disease”.

A 58-year-old married woman said:

“I hope I find a cure and I am healed. I always keep track of the news about this disease. I’m sure there is good news for us”.

A 38-year-old married man said:

“God willing, a treatment will be discovered, and we will be saved”.

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to evaluate the life experiences of HIV-positive patients. Through investigating the experiences that the interviewees mentioned about their lives with HIV/AIDS, we extracted four main themes: emotional and psychological disturbances, stigma, supportive environment, and patients’ perspective of the future.

The emotional and psychological disturbances theme shows that besides the physical aspect as the most dealt-with issue in society, AIDS has emotional and psychological aspects. Because of insufficient knowledge and awareness about HIV/AIDS, people in the community are more concerned with its physical dimension. Meanwhile, we found that in addition to the physical dimension, this infection has psychological dimensions that affect the patients.

The results showed that after the diagnosis of the infection, a major change in the way of life is experienced, which can cause psychological stress. The problems that patients face and affect their lifestyle is emotional and psychological disturbances, like the fear of death, the fear of being rejected by others, the fear of the uncertain future that awaits them, and the fear of the future awaiting their children (25-27).

In addition, depression is the most common psychological problem that almost all the researchers have mentioned about AIDS, which is the most important emotional and psychological complication of the disease (28-31). The results of this study showed that the patients had a sudden psychological shock when they were aware of their illnesses, affecting their lives leading to a depressive phase.

Another finding of this study regarding emotional and psychological disturbances was the feeling of being victimized. This feeling was more prevalent in women who were infected by their husbands, and they saw themselves as victims of their husbands’ mistakes and aberrations. They claimed that they did not make anything wrong to get the disease, and what annoys them is that other people in the community will not have a similar view, which results in making a false judgment about others.

The findings of this study regarding the theme of stigma indicated three concepts of fear of being exposed, false judgment, and discrimination. The stigma of HIV infection is undoubtedly the most prominent problem in these patients, as it is related to the reactions of the different strata of society, in which the individual lives, and most importantly it is closely linked to emotional and psychological disorders (16).

Seyed Alinaghi et al. (14) evaluated the stigma among PLWHA in six cities in Iran and showed that 62.2% of patients experienced external stigma (such as exclusion from family activities and social gatherings and being verbally insulted, harassed, or threatened), and 98.62% reported internal stigma (such as deciding not to attend social gatherings, not to get married, not to have sex, not to have children, stop working, withdrawal from education or training, etc.).

Another concept related to discrimination is that patients believe that hospital staff treats them differently than other patients. They complained about the lack of knowledge of hospital staff about the ways by which AIDS is transmitted. Lakshmi, in a study on the effect of lived experiences on HIV positive patients’ quality of life, reported stigma among health care workers in private hospitals (32).

The results of this study showed that secrecy and fear of disclosing the disease occur at both family and community levels, albeit much less at the family level, as many interviewees reported at least one member of their own family. This has had the most positive outcome for them, particularly if family members had knowledge about the infection, the patient would be supported and referred to appropriate treatment centers.

Supportive services and strategies are the other positive results of the experiences of the patients interviewed and have had a great positive impact on their lives. The results further showed that the first source of support is the family members. A large number of patients have shared information on their illness with their family members and have benefited from supports received from them. As a result, the family is the most important and almost the first source of patient support (32).

The other source of support that patients receive is the support from the Counseling Center for Behavioral Diseases. They reported that this is the only support center that provides them with limited medical, counseling, and psychological services. Regarding health, they did not receive services from other staff in other organizations.

The other results of this study showed that patients’ perspectives on their future are summarized in three parts: anxiety and fear about their future, worrying about children’s future and hoping for the future, and finding definitive treatment for the disease.

The findings of this study are in line with the results of Mohammadpour et al. (33). In their research, they showed that patients, on the one hand, had a fear of death, and on the other hand, had hope for healing, salvation, and life. In this research, some patients were directly afraid of death and they were worried about their children in the future. In a study on the experiences of PLHIV, Basanti and Mazaleni (34) reported sadness and worry of patients as a result of their deteriorating health, the grave prognosis, and the fate of their children.

The strengths of this study provided insight into the’ lived experiences with HIV/AIDS and expanded the understanding of living with HIV/AIDS as a minority population.

One of the limitations of this study was that participants were selected from those referred to Jahrom Counseling Center for Behavioral Diseases, Iran. Therefore, the results may be different from other patients who do not refer to these centers and cannot be generalized to all people of Iran due to a very diverse range of cultural, social, and religious backgrounds of the people in the country.

5.1. Conclusions

Despite the significant progress in the field of HIV/AIDS in recent years and considering the fact that it is now a manageable and chronic condition, the participants explained the fear of death, the fear of rejection, the fear of the future for themselves, and their children, depression, social stigma, and feeling victimized. The use of these terms was associated with its intolerance and the negative reactions of the community. In particular, the attitude of clinical staff towards AIDS should be changed by improving the education and designing a new curriculum on treatment and dealing with HIV cases because this was the most recurrent item that the patients complained about. Besides, developing educational programs for the public can greatly increase public awareness of HIV, change the attitudes and beliefs about HIV, and improve the behavior of others in dealing with PLHIV. This change of attitude creates social support and facilitates the acceptance of the infection for PLHIV. The need for improvement of social support, education, and counseling should be considered regarding HIV-infected individuals.