1. Background

In recent years, substance abuse disorders have become one of the most public health problems globally, and methamphetamine is the second most used illicit drug in the world, after cannabis (1). Abusing methamphetamine is associated with cognitive deficits (2) and affective problems (3, 4). Patients with chronic diseases experience high psychological problems and negative emotions such as anxiety and depression (4, 5). Addiction is a chronic disease, and individuals who use methamphetamine chronically show difficulties in emotion regulation. Studies highlight that methamphetamine use is associated with mood dysregulation, depression, and anxiety (6), possibly contributing to interpersonal behavioral problems and low quality of life (3, 7).

Emotion regulation refers to actions that influence individuals’ emotional responses during emotional processing that increases the risk of substance use (8, 9). Various studies have revealed affective dysregulation, mood problems, and depression in methamphetamine abusers (10). Methamphetamine abusers experience high levels of depression, anxiety, aggression, hostility, and irritability (11). Emotion dysregulation and affective problems are intensified by irregular daily activities, including sleep disturbance (12). Emotional problems are also related to the craving to use (13). It can increase the likelihood of slipping and relapse in drug abusers. Therefore, it is necessary to moderate emotional dysregulation as a major obstacle to treatment maintenance, treatment outcomes, and recovery in methamphetamine abusers.

In addition to emotional problems, methamphetamine is a highly addictive substance develope cognitive deficits, executive dysfunction, and abnormality in brain structures (14). In a study, methamphetamine users performed poorer than healthy people in all the components of executive functions such as working memory, attention, cognitive control, and decision-making (2). Methamphetamine abusers experience moderate impairment in most cognitive domains, including attention, executive functions, language/verbal fluency, visual memory, and working memory, although deficiencies in impulsivity/reward processing, inhibitory response, and social cognition are more prominent (15). The long-term use of methamphetamine is associated with deficits in cognitive functioning, including decision-making, response inhibition, planning, working memory, and attention (16). Methamphetamine abuse/dependence brings about difficulties in all cognitive aspects such as reaction time, attention/working memory, executive functions, learning, memory, motor skills, language, and speed of information processing (15). Besides, methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) causes cognitive deficits and more importantly, impairments in executive functions (15). Other studies demonstrated that although executive functions may be increased by the avoidance of using methamphetamine, they are not completely removed (17), and abstinent individuals experience persistent neurocognitive deficits (18). Cognitive deficits may predate the start of drug use in abstinence individuals (19). Thus, intervention programs seem to be necessary for improving executive functions, especially response inhibition and impulsivity, in methamphetamine-dependent people.

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy (IPSRT) improves people’s mood and sleep quality by reducing irregularity related to lifestyle (20). Developed by Ellen Frank for the treatment of bipolar disorder, IPSRT leads to stable mood and emotion regulation and increases the periods of wellness by reducing interpersonal problems and regulating circadian rhythms (21). Due to the severity of mood and emotional fluctuations in methamphetamine abusers, as well as serious problems in the rhythm of sleep and wakefulness making daily activities difficult which in this respect is comparable to people with bipolar disorder, therefore, considering the effectiveness of IPSRT in improving the mood and daily lifestyle of people with bipolar disorder (22), we expected that it is an effective treatment for modulating emotion dysregulation in people with methamphetamine abuse.

Executive dysfunction in methamphetamine abusers is related to a low level of treatment maintenance and treatment outcomes (23). On the other hand, other cognitive dysfunctions and impairments in inhibitory control are related to higher drop-out rates in continuing treatment (24) and relapses in methamphetamine abusers. Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy (CRT) that includes the practice of cognitive tasks involving memory, problem-solving, response inhibition, perception, and discrimination skills (16) is one way to enhance executive functions. In recent years, technological advancements allow using computer-based Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy to improve neurocognitive deficits in patients. Bickel demonstrated that the training of computerized memory tasks modified impulsivity and delayed discounting among stimulant abusers (25).

Despite the evidence of emotional dysregulation and cognitive deficits in methamphetamine abusers and a strong association between cognitive and emotional deficits and treatment outcomes, only a few studies have investigated the efficacy of IPSRT and CRT in methamphetamine abusers. Therefore, in this study, we added CRT to IPSRT and investigated its efficacy in executive functions and emotion dysregulation in methamphetamine Abusers.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to answer the following question: Is adding Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy (CRT) as an adjunct treatment to Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy (IPSRT) more effective than IPSRT alone in reducing emotion dysregulation and improving executive function in methamphetamine abusers during the early abstinence phase?

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Participants

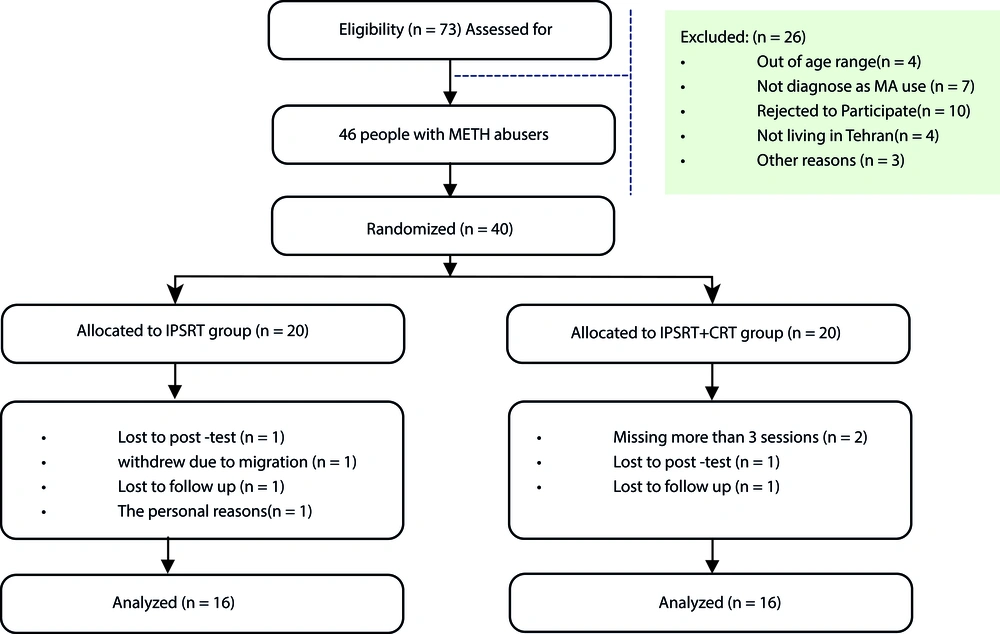

Forty participants who fulfilled the DSM-V (diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition) criteria for methamphetamine use disorder were selected from drug rehabilitation centers between April 2018 and September 2020 in Tehran (mean age = 28.1, SD = 5.62). Subjects were selected based on the inclusion criteria: (1) Age range of 20 - 45; (2) fulfilling the DSM-V criteria for methamphetamine use disorder; (3) at least 12 months’ history of methamphetamine use; (4) the absence of other substance-dependent disorders except for smoking; and (5) the ability to speak and write Farsi sufficiently. The exclusion criteria were (1) having a history of psychiatric (bipolar disorder, major depression, or psychoses) or neurological disorders; (2) history of a suicide attempt recently; (3) the absence of other substance-dependent disorders except for smoking; and (4) using antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs during the study. The participants were randomly assigned to the IPSRT (n = 20) or IPSRT + CRT (n = 20) groups. Four subjects from the IPSRT group and four from the IPSRT + CRT group withdrew before the study was completed. Therefore, the final analysis was conducted with 16 subjects of the IPSRT group and 16 subjects of the IPSRT + CRT group (Figure 1).

All participants were asked to complete the assessment tools at the pretest, posttest, and four-week follow-up. The IPSRT group received Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy during 12 sessions of 45 - 55 min with a frequency of two sessions per week, and the IPSRT + CRT group received both Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy and CRT including PARISA for 12 sessions (two sessions per week, 50 - 60 min sessions).

3.2. Intervention

3.2.1. Description of IPSRT

Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy (26) consisted of 12 sessions of 45-55 min in three stages: Primary, middle, and final. The first phase was presented in the first four sessions and included familiarity and gathering information about the history of addiction and methamphetamine use, knowledge of the nature of addiction, collecting information about important others and the participant’s relationship with them, expectations from the relationship, positive and negative aspects of the relationship, determining the status of circadian rhythms such as sleep/wake habits and eating, identifying irregularities in these rhythms, providing education about addiction disorder and bidirectional relationship between mood and interpersonal events, major life events such as the death of a loved one, changes in living conditions, discussion of interpersonal conflicts, role changes, interpersonal deficiencies of addicts, identifying and defining interpersonal disturbance and reviewing practical solutions to resolve these disputes and improve communication, reducing interpersonal disturbance and social isolation through social skills, and strengthening the existing relationships and helping build new ones. The middle phase was presented in the fifth to eighth sessions and included helping implement stabilization strategies for circadian rhythms, providing strategies to regulate emotions and mood, awareness of the relationship between emotion and craving, slipping, relapse, and its management, the relationship between the patient’s mood and his relationships with important people in life, and identifying interpersonal problem areas and developing procedures to resolve them. The final phase in the ninth to 12th sessions included monitoring and evaluating mood and strategies used to regulate emotional fluctuations, evaluating the strategies used to develop interpersonal relationships, predicting challenging situations in future interpersonal relationships, reviewing strategies to manage them, and discussing the possibility of craving and slipping and how to manage it after the treatment sessions.

3.2.2. Description of CRT Program

Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy included program for attentive rehabilitation for inhibition and selective attention (PARISA). The PARISA is a computer-based cognitive rehabilitation and neurocognitive education program for cognitive rehabilitation of inhibitory control (27). The PARISA protocol covers six computerized progressive tasks: Face arrangement task, box packing task, fishing task, hat choosing task, traffic sign control task, and rabbit-turtle competition. Each task has 10 levels of difficulty that could be elected based on trainee performance. These tasks can be useful to help three types of inhibitory control, including interference control, prepotent inhibition, and selective attention.

3.3. Instruments

3.3.1. Go/No-Go Task

The Go/No-Go test is one of the neurocognitive tasks most universally used for evaluating inhibitory control. Response inhibition is one of the components of executive functions, which is strongly associated with cognitive control (28). It is used to measure a participant’s ability for sustained attention and response control. For example, the Go/No-Go test needs a participant to perform certain stimuli (e.g., press a button-Go) and inhibit that action under a different set of stimuli (e.g., not press the same button-No-Go).

3.3.2. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) is a self-assessment scale designed for measuring emotion dysregulation. The original DERS includes 36 items scored on a Likert scale (1 - 5), including 1 rarely, 2 some time, 3 about half the time, 4 most of the time, and 5 almost always. The DERS-36 yields a total score on six subscales (awareness, clarity, goals, impulse, non-acceptance, and strategies), and higher scores indicate more difficulties in emotion regulation (29). A study reported the test-retest validity of 0.84 and internal consistency by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 (30).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Mixed repeated ANOVA was used to analyze the data. The time was used as the within-group factor (pre-intervention, post-intervention, follow-up) and group (IPSRT and IPSRT + CRT) as the between-subject factor. The pairwise comparisons were conducted by the Bonferroni test. The data were analyzed by statistical software SPSS version 26 and Graph Pad Prism-7.

3.5. Research Ethics

The independent ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University (code: IR.SBU.REC.1398.048) approved the present research. The study complied with the ethical principles in the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants were explained about the purpose and procedure of the study. Also, it was declared that they were free to withdraw at any time.

4. Results

The mean age (standard deviation) of all participants was 28.65 (5.69). The mean age of substance use onset was 18.77 (3.94). Regarding marital status, 22 (68.7%) participants were single, and 10 (31.3%) participants were married. In terms of Job status, 14 (43.8%) participants were unemployed, 13 (40.6%) participants had a part-time job, and five (15.6%) participants were employed. About substance use in the family, 15 (46.875) participants answered “no” and 17 (53.13%) reported a history of substance use in the family. The findings demonstrated no significant differences between the two groups in demographic variables, including gender, job status, marital status, and age, as well as substance use characteristics (Table 1).

| Variable | IPSRT (N = 16) | IPSRT + CRT (N = 15) | Statistical Analyses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 16 | 16 | |

| Female | 0 | 0 | |

| Age, y | 29.43 (6.02) | 27.87 (5.42) | t(30) = 0.77, P = 0.44 |

| Age of substance use onset, y | 18.12 (3.71) | 19.43 (3.41) | t(30) = 1.04, P = 0.31 |

| Job status | χ2(3) = 1.18, P = 0.55 | ||

| Unemployed | 6 | 8 | |

| Part time | 8 | 5 | |

| Employed | 2 | 3 | |

| Marital status | χ2(1) = 0.58, P = 0.44 | ||

| Single or divorced | 12 | 10 | |

| Married | 4 | 6 | |

| Substance use in family | χ2(1) = 1.12, P = 0.28 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 7 | |

| No | 6 | 9 | |

| Education, y | 10.18 (2.37) | 9.43 (2.67) | t(30) = 0.86, P = 0.39 |

Abbreviation: n, number of subjects.

aValues expressed as mean (SD).

bChi-square and independent t-test were used for analyzing differences between groups in demographic variables.

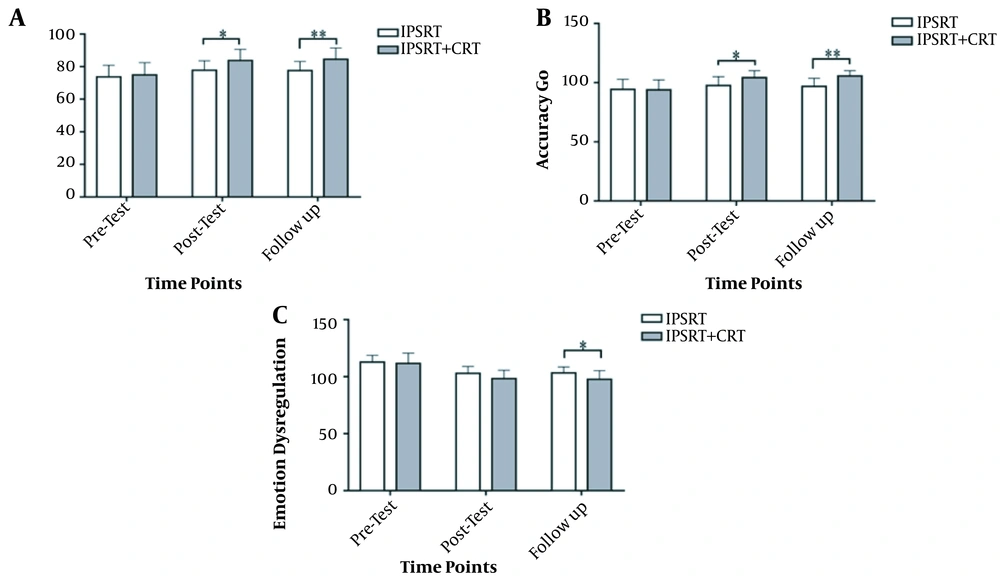

Mixed repeated ANOVA was conducted to examine the differences between the IPSRT + CRT and IPSRT groups in the components of executive function. The results showed that in all components, the main effect of the group was significant. In No-Go accuracy, the group (IPSRT + CRT vs. IPSRT) as between-subject and the assessment time (pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up) as within-subject were tested. Similarities were found between the two groups at pretest, but there were significant differences between IPSRT and IPSRT + CRT groups [F(1, 30) = 4.77, P ≤ 0.05, η2 = 0.14], between-subject by within-subject interaction effect (time*group) [F(2, 60) = 44.66, P ≤ 0.01, η2 = 0.16] and within-subject effect (time) [F(2, 60) = 40.98, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.58]. In Go Accuracy, the group (IPSRT + CRT vs. IPSRT) as between-subject and the assessment time (pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up) as within-subject were tested. There were significant differences between the IPSRT and IPSRT + CRT groups [F(1, 30) = 4.28, P ≤ 0.05, η2 = 0.13], between-subject by within-subject interaction effect (time*group) [F (1.26, 37.99) = 30.68, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = .58] and within-subject effect (time) [F(1.26, 37.99) = 84.91, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.74] (Tables 2 and 3).

| Group | Numbers | Pretest, Mean ± SD | Posttest, Mean ± SD | Follow-up, Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSRT | 16 | 94.31 ± 8.53 | 97.56 ± 7.48 | 96.75 ± 6.90 |

| IPSRT + CRT | 16 | 93.94 ± 8.33 | 104.19 ± 5.96 | 105.50 ± 4.67 |

| Total | 32 | 94.13 ± 8.30 | 100.88 ± 7.46 | 101.13 ± 7.31 |

| Group | Numbers | Pretest, Mean ± SD | Posttest, Mean ± SD | Follow-up, Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSRT | 16 | 73.44 ± 7.15 | 77.81 ± 5.85 | 77.63 ± 6.56 |

| IPSRT + CRT | 16 | 74.94 ± 7.55 | 83.78 ± 6.86 | 84.56 ± 6.91 |

| Total | 32 | 74.19 ± 7.28 | 80.81 ± 6.97 | 81.09 ± 7.51 |

aSignificant (P ≤ 0.05).

In emotion dysregulation, the group (IPSRT + CRT vs. IPSRT) as between-subject and the assessment time (pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up) as within-subject were tested. There was no significant difference between the IPSRT and IPSRT + CRT groups [F(1, 30) = 2.35, P = 0.13, η2 = 0.07], between-subject by within-subject interaction effect (time*group) [F(2, 60) = 18.06, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.38] and within-subject effect (time) [F(2, 60) = 589.41, P ≤ 0.001, η2 = 0.95]. In general, the results of between-group differences demonstrated that both IPSRT and IPSRT + CRT were effective although the combination of IPSRT with CRT was more effective (Figure 2 and Tables 4 and 5).

| Group | Numbers | Pretest, Mean ± SD | Posttest, Mean ± SD | Follow-up, Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPSRT | 16 | 112.75 ± 6.07 | 102.88 ± 6.02 | 103.25 ± 5.32 |

| IPSRT + CRT | 16 | 111.69 ± 8.98 | 98.31 ± 7.34 | 97.69 ± 7.57 |

| Total | 32 | 112.22 ± 7.56 | 100.59 ± 7.02 | 100.47 ± 7.04 |

Abbreviations: CRT, Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy; IPSRT, Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy.

| Task | Outcome Measures | Source | df | f | P | Eta | Pairwise Comparisons (Bonferroni) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Go/No-Go | No-Go accuracy | Time | 2 | 40.98 | 0.001a | 0.58 | IPSRT + CRT > IPSRT |

| Group | 1 | 4.77 | 0.037a | 0.14 | |||

| Time*group | 2 | 44.66 | 0.006a | 0.16 | |||

| Go/No-Go | Go accuracy | Time | 1.26 | 84.91 | 0.001a | 0.74 | IPSRT + CRT > IPSRT |

| Group | 1 | 4.28 | 0.047a | 0.13 | |||

| Time*group | 1.26 | 30.68 | 0.001a | 0.51 | |||

| Emotion dysregulation | Time | 2 | 589.41 | 0.001a | 0.95 | IPSRT + CRT < IPSRT | |

| Group | 1 | 2.35 | 0.136 | 0.07 | |||

| Time*group | 2 | 18.06 | 0.001a | 0.38 |

Abbreviations: CRT, Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy; IPSRT, Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy.

a Significant (P ≤ 0.05).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy (IPSRT) and adding CRT to IPSRT in reducing emotional dysregulation and improving executive function, especially inhibitory response, among methamphetamine abusers. The findings showed that the combination of IPSRT with CRT was significantly more effective than IPSRT for reducing emotion dysregulation and improving executive function in methamphetamine abusers. Studies show the effectiveness of IPSRT in improving mood and emotion regulation. For example, IPSRT reduced the depression scores in PTSD among depressed patients and people with sleep disorders (20). A study also confirmed the effectiveness of social rhythm-based therapy in decreasing depression in people with major depressive disorder (31). Other studies have revealed the efficacy of IPSRT in modulating depression and preventing recurrence in patients with bipolar disorder (26), and improving the mood symptoms in at-risk adolescents with bipolar disorder (22), all of which are compatible with the results achieved in the present study.

According to the social rhythm hypothesis of depression, daily routine disruption can lead to instability in specific biological rhythms, such as sleep, and intensify negative emotions (32). Lifestyle irregularity is one of the most complaints in methamphetamine, sometimes awake for up to 30 hours after consumption and, sleep disturbance may explain depression and low mood in METH users (33). Also, lifestyle irregularity is associated with greater health problems, depression, anxiety, and stress. Interpersonal treatment of social rhythms, by regulating daily activities and circadian rhythms such as sleep/wake cycles, has a positive impact on both depressed mood and functioning of methamphetamine abusers (32). Regulating the sleep/wake cycle reduced depression in patients with mood disorders (31). Besides, IPSRT by improving interpersonal relationships, expanding the social network, and providing social support (31) can indirectly reduce emotional fluctuations. The present study introduces a new model for treating addiction that emphasizes the importance of interpersonal relationships and biological rhythms.

The current study demonstrated that adding Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy to IPSRT enhanced neurocognitive dysfunctions in subjects with methamphetamine use disorder. The findings agree with evidence that CRT may have beneficial consequences for cognitive function in methamphetamine abusers. Previous reports demonstrated the efficacy of CRT on cognitive function in substance abusers (34, 35). Methamphetamine abusers experience cognitive deficits such as executive function, attention, social cognition, flexibility, inhibitory response (36), inhibitory response, and self-regulation (15, 16). It might break down psychological interventions (37) and executive dysfunctions, especially inhibitory control, which explain the high rate of relapse even after long-term abstinence in substance abusers (36). Cognitive rehabilitation by promoting inhibitory skills (38) can decrease the probability of relapse in substance abusers.

Emotion dysregulation and executive dysfunction are threatening problems in methamphetamine abusers that affect treatment outcomes, so we added CRT to IPSRT to improve emotion regulation and cognitive functions. The findings demonstrated that there was a considerable difference between the IPSRT and IPSRT + CRT groups in all cognitive functions and difficulties in emotion regulation, and improving cognitive function and emotion regulation continued for four weeks after the intervention in the IPSRT + CRT group.

5.1. Conclusions

This study is the first to support the effectiveness of adding Cognitive Rehabilitation therapy to Interpersonal and Social Rhythm therapy to improve executive functions and emotion regulation in people with methamphetamine use disorders. Emotion dysregulation and neurocognitive impairments not only affect the quality of life but also make the abstinence and recovery process in METH abusers more difficult. The combination of IPSRT with CRT can be considered a valuable treatment for improving neurocognitive dysfunctions and mood in substance abusers.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several restrictions that need to be considered in future studies. First, all participants in the present study were men, and it did not include women subjects, whilst the efficacy of these interventions may be different in men and women. The present study showed the durability of the intervention after four weeks, so investigating the permanence of IPSRT + CRT after three or six months can be suggested for future studies.