1. Background

Over the last twenty years, the use of technology has been more widespread, particularly among adolescents using digital media for education, communication, and entertainment (1). According to the statistics, adolescents use technology for > 7.5 hours per day, and they spend 25% of the same time to use multiple media simultaneously (2). Today, most adolescents possess computers and cell phones, with their positive and detrimental consequences (3-5). These tools has recently raised a new type of violence, called “cyberbullying”, thereby arousing concerns among many parents, teachers, and mental health authorities as it can threaten adolescents’ mental and physical health (6). On the other hand, given that adolescence is a period of gaining experiences in social relationships, oppression and oppression acceptance can predict individuals’ role in adulthood and the professional and social environment (7).

Cyberbullying is a term describing aggressive or intentional harassment by a person or a group over time, which can be exhibited in the form of physical, verbal, and communicative behaviors (8). Most definitions of cyberbullying have been modeled from traditional bullying (9). Individuals’ perceived roles in the traditional forms of bullying also apply to cyberbullying by including terms such as sinister persons, victim, and witness (10). Cyberbullying has even increased the severity of bullying due to its potentially unlimited audience, hidden nature of bully, and its uncontrollability. Moreover, cyberbullying face no limitation in space and time and target individuals in their private home environment at any daytime (9). Such bullying may be accompanies with sending humiliating, threatening, and annoying messages, images, and videos (11).

Recent studies have revealed that about 20% - 40% of individuals have experienced cyberbullying at least once in their adolescence (12), and that cyber harassment can arouse depression and anxiety in 68% of people (13). Experiencing cyberbullying is a dangerous motive for future misconduct, including drug abuse, delinquency, and suicidal ideation. This is, while decreasing antisocial behaviors in minors is one of the priorities of social policies. Only 10% of studies addressing such issues have been conducted in low-income and middle-income countries (14). Jaghoory et al. (15) described cyberbullying among Iranian teenagers to be common. In Razjouyan et al.’s study (10), 32% of the participants were victims, 27% were bullied, and a majority of the victims were female.

However, given the novelty of this phenomenon, few studies have dealt with the profiles of intruders and victims of cyberbullying among Iranian adolescents. As the adolescents’ increasing use of telecommunication tools is associated with cyberbullying, the prevalence of this phenomenon and its contributing factors should be examined to prevent further detrimental consequences.

2. Objectives

The study aimed to examine the prevalence of experiencing exposure to cyberbullying among adolescents in Tehran and test the hypothesis indicating that the experience of cyberbullying is correlated with some characteristics of the respondents.

3. Materials and Methods

We in collaboration with Tehran Education Organization, conducted a cross-sectional study on four randomly-selected high schools (two girls’ high schools and two boys’ high schools) in District 17, Tehran, Iran. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code: 8823101026). The samples were selected from each school using the simple random sampling method (n = 288). In boys’ schools, five out of nine classes were selected with a mean frequency of 27 students, and in girls’ schools, five out of 10 classes were selected with a mean frequency of 30 students.

The study instrument directly interpreted the findings of a previous study entitled “Investigating the phenomenon of bullying via new communication and information technologies in high schools in Tehran and its relationship with emotional intelligence” (16). The questions addressed three domains: (A) The experience of being cyberbullied, the cyberbullying method, sinister persons, frequency of harassment, and disclosing experience; (B) the experience of making attempts at cyberbullying, the bullying method, the frequency of harassment, and victims; and (C) close friends’ exposure to cyberbullying, supportive measures, feelings about a friend’s experiencing cyberbullying, and a general attitude towards cyberbullying as harmful. Six experts confirmed the content validity of the questionnaire using content validity index (CVI = 0.96). Test-retest technique was adopted to check the questionnaire reliability. To this end, the questionnaire was distributed among 15 students to be completed, and after a two-week interval, it was completed once more by the same students. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were 0.85 for the experience of being cyberbullied, 0.80 for the experience of attempts at cyberbullying, and 0.70 for close friends’ exposure to cyberbullying.

The questionnaires were distributed among the selected students aged 13 - 18 years. First, the participants were ensured that the collected data would be kept confidential and that the findings would be published anonymously. The other provisions of the Helsinki Regulations were also considered.

Data were analyzed with SPSS software, and frequency and percentage were used for descriptive analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the normal distribution of the quantitative data. To describe the relationship between demographic variables and the respondents’ experience of being bullied and bullying, the chi-square test was used for the nominal variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare age. In this study, P < 0.05 was set as the significance level.

4. Results

The participants’ age ranged from 13 to 18 years, with the mean age of 15 years. Among the participants, 136 persons (47.9%) were male, and 150 persons (52.1%) were female; 135 persons (46.87%) were studying in primary high schools, and 153 individuals (53.12%) were studying in secondary high schools. Of the individuals selected from the secondary high school students, 62 persons (45.3%) were studying mathematics, and 75 persons (54.7%) were studying the experimental sciences. The findings showed that 90 (33%), 100 (37%), and 82 (3%) individuals spent < 5 hours, between 5 - 15 hours, and > 15 hours per week on the Internet and mobile phones. One hundred forty-one respondents (49%) also believed that cyberbullying was harmful. Table 1 provides information on the respondents’ experience about being cyberbullied, attempts at cyberbullying, and their close friends’ exposure to cyberbullying.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| A) Cyberbullied | |

| Yes | 89 (30.90) |

| No | 199 (69.10) |

| Cyberbullying method | |

| Internet (websites or social media) | 59 (66.29) |

| Telephone (messages or calls) | 30 (33.71) |

| Sinister person | |

| Other students | 23 (25.84) |

| Individuals out of school | 21 (23.60) |

| Strangers | 45 (50.56) |

| Frequency of harassments | |

| Weekly | 22 (25.00) |

| Monthly | 66 (75.00) |

| Disclosing experience | |

| Yes | 42 (47.73) |

| No | 46 (52.27) |

| B) Attempt at cyberbullying | |

| Yes | 85 (29.82) |

| No | 201 (70.53) |

| Bulling methods | |

| Internet (websites or social media) | 62 (72.94) |

| Telephone (messages or calls) | 23 (27.06) |

| Frequency of harassments | |

| Weekly | 38 (44.70) |

| Monthly | 47 (55.29) |

| Victim | |

| Inside the school | 16 (18.82) |

| Outside the school | 69 (81.18) |

| C) Friends’ exposure to cyberbullying | |

| Yes | 117 (40.62) |

| No | 171 (59.38) |

| Supportive measures for a friend being cyberbullied | |

| No action | 61 (54.5) |

| Dealing with a sinister person | 21 (18.92) |

| Empathy with friends | 17 (15.31) |

| Informing a parent or a teacher | 13 (11.71) |

| Feelings about a friend’s experiences of cyberbullying | |

| Worried | 51 (50.00) |

| Indifferent | 31 (30.39) |

| Interested | 20 (19.61) |

Of the respondents, 89 cases (30.90%) had the experience of being cyberbullied, most of whom were bullied via the Internet (66%). The harassment was mainly imposed by strangers (50%) and monthly (75%). Most of the bullied samples (52%) refused to disclose their experience.

As presented in Table 1, 85 respondents (29.82%) reported their attempts to bully others online. Most cases of harassments are via the Internet (73%) and are repeated monthly (55%). In these harassments, 70% of the victims are of the opposite gender and from out of school (48 out of 69 victims).

Table 1 also shows that 117 persons (41%) have close friends with the experience of being cyberbullied and are mainly passive about the event (54%). However, their friends’ exposure to cyberbullying made most of the participants (50%) worried. This is while some of the participants felt indifferent (30.39%) or interested (19.61%).

Regarding the participants’ general attitude towards cyberbullying, 141 persons (49%) confirmed that it was harmful, 97 cases (33.7%) stated no idea, and 48 individuals (16.7%) denied the harmfulness of cyberbullying.

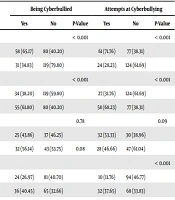

Table 2 presents the relationship between the respondents’ demographic variables and their experience of attempts at cyberbullying and being cyberbullied. Accordingly, the two variables ‘female gender’ and ‘secondary high school education’ significantly increase the likelihood of experiencing attempts at bullying and being bullied (P < 0.001). Moreover, there is a significant relationship between increased time to use virtual tools per week and aging with attempts at bullying (P < 0.001). Furthermore, a significant relationship is also observed between being bullied and attempts at bullying (P < 0.001). Forty-three persons (50.6%) with the history of making attempts at bullying had the experience of being bullied.

| Variables | Being Cyberbullied | Attempts at Cyberbullying | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P-Value | Yes | No | P-Value | |

| Gender | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Female | 58 (65.17) | 80 (40.20) | 61 (71.76) | 77 (38.31) | ||

| Male | 31 (34.83) | 119 (79.80) | 24 (28.23) | 124 (61.69) | ||

| High school | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Primary | 34 (38.20) | 119 (59.80) | 27 (31.76) | 124 (61.69) | ||

| Secondary | 55 (61.80) | 80 (40.20) | 58 (68.23) | 77 (38.31) | ||

| Field | 0.78 | 0.09 | ||||

| Mathematical | 25 (43.86) | 37 (46.25) | 32 (53.33) | 30 (38.96) | ||

| Experimental | 32 (56.14) | 43 (53.75) | 0.08 | 28 (46.66) | 47 (61.04) | |

| Time to use virtual tools per week, h | < 0.001 | |||||

| < 5 | 24 (26.97) | 81 (40.70) | 10 (11.76) | 94 (46.77) | ||

| 5 - 15 | 36 (40.45) | 65 (32.66) | 32 (37.65) | 68 (33.83) | ||

| > 15 | 29 (32.58) | 53 (26.63) | 39 (45.88) | 43 (21.39) | ||

| Median of age, y | 16 | 15 | 0.052 | 16 | 15 | < 0.001 |

In response to the respondents’ feelings about their friend’s experience of being cyberbullied, a majority of female respondents (n = 24; 66%) felt worried, 7 persons (19.4%) found it interesting, and 5 individuals (13.9%) were indifferent. Among the male respondents, 31 persons (40.8%) felt worried, 29 cases (38.5%) were indifferent, and 16 individuals (21.1%) were interested. In this regard, the difference between the two gender groups was significant (P = 0.017).

In response to the reactions to their friend’s experience of being cyberbullied, a majority of female participants (n = 17; 47.2%) adopted no measure, 11 persons (30.6%) expressed empathy with their friends, 6 cases (16.7%) tried to deal with the sinister person, and 2 individuals (5.6%) informed their parents or teachers. Regarding the reactions of the male respondents, 44 persons (57.9%) adopted no measure, 15 individuals (19.7%) tried to deal with the sinister person, 11 cases (14.5%) informed their parents or teachers, and only 6 persons (7.9%) expressed empathy with their friends. In this regard, there was a significant difference between the two gender groups as well (P = 0.014).

5. Discussion

With an increase in adolescents’ access to telecommunications devices, the likelihood of cyberbullying have also enhanced; hence, the present study was to investigate the prevalence of cyberbullying among Iranian adolescents and detect its contributing factors.

According to the findings of the present study, 30.90% of the participants experienced cyberbullying. In Lee and Shin’s study (17), bullies (6.3%), victims (14.6%), and both bullies and victims (13.1%) were Korean adolescents with an experience of cyberbullying. Calmaestra et al. (18) found out that one out of four adolescents in Ecuador and one out of five adolescents in Spain are involved in cyberbullying. To justify the inconsistencies in these studies, we can mention that there were differences among the tools and samples. In support of this finding, Brochado et al. (19) stated that the estimated prevalence of cyberbullying is affected by the research method.

Further findings indicated that the bullied students are often avoided disclosing their experiences due to the feelings of embarrassment and weakness, being concerned with not worrying their parents, and fear of being deprived of communication (20). In a study by Rad on Romanian adolescents, the main predictor of continued cyberbullying was silence in response to the bully’s behaviors (21). Moreover, female gender and education in the secondary high school significantly increased the likelihood of experiencing harassment (P < 0.001). In other studies, researchers have reported similar findings regarding the higher prevalence of cyberbullying in females (22, 23). To justify its higher likelihood among girls, the oft-obedient and passive behavior of this group in dealing with harassment can be regarded, which encourages the sinister person to bully others (24). However, since using technological tools for students’ academic progress is now quite common and inevitable, the high prevalence of harassments necessitates the principled training of students, especially girls, to make them familiar with the appropriate use of tools and harassment cases. Appropriate culture nurturing is also necessary to break the culture of silence among the victims of harassments.

In this study, 29.82%% of the participants used to bully others online. In Yilmaz’s study (25), 6.4 % of the samples were bullies. This difference could be due to the respondents’ attitudes towards the benefits and harms of confessing to bullying. However, motives such as fun, revenge, stress relief, personal distress, power, attention seeking, and suffering from the others’ happiness can encourage the bullies to harm others (26).

Our study suggested that most cases of cyberbullying were monthly addressing individuals outside the school and of the opposite gender. Hoff and Mitchell (27) described its relationship with the opposite gender as one of the most important and common factors affecting the likelihood of cyberbullying. Cyberbullying is likely to be exacerbated in an Islamic society due to the secrecy of the relations between the two genders. Moreover, female gender, secondary high school education, age, and duration of using telecommunications tools significantly affected bullying (P < 0.001). Previous studies have confirmed that the excessive and unwarranted use of these tools, especially the Internet, can pave the way for cyberbullying (28). Young and Govender found a similar finding regarding the effect of age on adolescent students’ higher tendency to cyberbullying (29). Due to the declining power of parental and teacher supervision over older students, self-centeredness is highly noticeable in this group. Accordingly, their internal deterrent power must be strengthened (30). This is, while girls’ tendency towards covert behaviors to harass others has attracted researchers’ attention (31). As Ortega-Barón et al. (32) mentioned, males’ attitudes towards violating social norms are more pleasant, and they are more involved in direct violent behaviors in the school environment than females. The virtual platform is highly suitable for such harassments because of the unidentified bullying identities, and that there is no victim response, and the likelihood of punishment is lower.

Furthermore, the experience of being bullied was significantly associated with the experience of bullying (P < 0.001). Several studies have acknowledged the role of bullying-victimization among students (33, 34). In Bae’s study (35), exposure to high-risk online content was positively associated with cyberbullying. Cyberbullying was significantly less reported among students considering cyberbullying as dangerous and illegal (35).

The findings revealed that 41% of the participants had some abused friends and often reacted passively (54%). However, their being informed of their friends’ being bullied made most of the participants (50%) worried. In line with this finding, Shemesh’s study on adolescents aged 9 - 18 years revealed that more than 64% of the samples witnessed cyberbullying, and only 44% of witnesses helped the victims actively (36). In a study by Pepler, adolescents reported that the witnesses of cyberbullying experience different emotions, from discomfort and anger to moral dilemmas and justification. According to the findings, females with abused friends were significantly more worried than males, while males found bullying their friends more interesting (P = 0.017). In response to their friends’ bullying and violence, females were significantly more likely to empathize than males, and the males showed a higher tendency to be more passive (P = 0.014). In a similar vein, Baker claimed that females have more supportive attitudes toward victims than males, and that they tend to make the victim feel comfortable and provide him/her with some advice (37).

Regarding the general attitudes towards cyberbullying, only 49% of the respondents confirmed this phenomenon as harmful. Accordingly, there is an urgent need for promoting individuals’ awareness and information about the types of cyberbullying and its harmfulness and developing an educational program for adolescents to learn how to deal with this phenomenon.

The present study had some limitations, including some respondents’’ failure to understand the questions, their uncertainty about information confidentiality, or distorted facts. The researchers spared their efforts to eliminate such shortcomings during the questionnaire completion phase.

5.1. Conclusions

Cyberbullying is common phenomenon among Iranian adolescents. Unlike the general belief, the use of the Internet was no different among the abused adolescents; however, it was more frequently used by the abusive students. Unfortunately, the abused adolescents may choose this behavioral pattern to protect themselves and harass other peers. According to the study findings, the authorities are recommended to implement appropriate educational programs to increase adolescents’ awareness of cyberbullying and culturalization to exploit new communication tools at the school and community levels.