1. Background

The family is the central nucleus of any society and a center of maintaining mental health, with a vital role in shaping children's personalities (1). One of the family phenomena that has been considered by researchers, sociologists, and psychologists today is domestic violence or the so-called violence of men against women in the family (2). Domestic violence is defined as violent behavior or intentional control by a person in close contact with the victim. Controlling behavior may include physical harassment, rape, emotional harassment, financial control, and social isolation of the victim, which occur in any society with any racial, social, economic, educational, or religious background (3).

Domestic violence during pregnancy is a serious problem usually hidden and undetected (4, 5). Violence during pregnancy with direct and indirect mechanisms affects the health of the mother and fetus. It leads to adverse pregnancy consequences, including increased risk of premature delivery, low-birth-weight, abortion, stillbirth, premature placental abruption, prenatal bleeding, low Apgar score, low birth weight (LBW) during pregnancy, high blood pressure, and depression during pregnancy and after childbirth (4, 6). Pregnancy can affect the prevalence of domestic violence during this period for various reasons such as decreased sexual relations, misconceptions, and unnatural feelings about pregnancy (7).

In the United States, 152,000 to 324,000 pregnant women report physical and psychological violence annually (8). Studies from India show that 26.9% of pregnant women are physically abused, 29% are psychologically abused, and 6.2% are sexually abused; 47% are abused by their husbands, and 31% by other family members (9). In a study by Moazen et al., more than half of the women had experienced domestic violence at least once in their lifetime (10). Also, Sheikhbardsiri et al. reported that the most common types of violence against women were psychological/verbal (58%), physical (29.25%), and sexual violence (10%) (11).

In Sistan and Baluchestan province and Chabahar city, according to the traditional culture and belief in male ownership of women, low level of literacy, early marriage, polygamy, early and consanguineous marriages, and the taboo of separation and divorce, violence against women is far more widespread and common than can be assumed; so violence by men against spouses or fathers and brothers against daughters and sisters is sometimes considered desirable and necessary (12).

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to determine the severity and frequency of domestic violence among pregnant women in Chabahar.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted among pregnant women referred to the comprehensive health service centers in Chabahar, Iran, in 2020. The inclusion criteria included Iranian pregnant women with good mental health (with no medical history). They were excluded from the study if they were addicted or smokers or were unwilling to continue cooperation.

Several studies have shown that the prevalence of domestic violence in different societies can vary significantly between 25% and 73% (10, 11, 13). The present study used the lowest prevalence of 25% to determine the sample size. The sample size was calculated to be 350 people considering the accuracy of 0.05 and the confidence interval of 95%. The sample size was eventually increased to 400 people to improve accuracy. A random cluster sampling method was followed in which, first, the comprehensive health service centers of Chabahar city were listed. Then, among 20 active comprehensive health service centers, 12 health service centers were randomly chosen from different areas of the city. Sampling continued from Saturday to Thursday every week for three months to collect data.

3.2. Data Collection Tool

We used the Dispute Resolution Measures Scale, introduced by the World Health Organization, as a standard instrument to assess domestic violence (14). The tool consisted of two parts. The first part consisted of five questions (job, husband's job, education, husband's education, and marriage duration). The second part consisted of 27 questions in three areas (psychological violence, physical violence, and sexual violence). Psychological violence had eight questions, physical violence had 12 questions, and sexual violence had seven questions. Each question had eight options, and the scores ranged from 0 to 7. The options' scores were as follows: "This has never happened" = 0, "It did not happen in the past year, but it has already happened" = 1, "It happened once in the last year" = 2, "It happened twice in the last year" = 3, "It happened 3-5 times in the past year" = 4, "It happened 6 - 10 times in the past year" = 5, "It happened 11 - 20 times in the past year" = 6, and "It happened more than 20 times in the past year" = 7. We summed the scores obtained in each section to determine the severity of violence in each dimension; thus, the raw numbers were obtained and used in data analysis. Then, based on the obtained score, the subjects were divided into five groups: Very mild, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe.

The present study questionnaire has been developed and validated by Khosravi et al. The validity of this questionnaire was determined using content validity by specialists. Cronbach's alpha coefficient determined its reliability on 29 participants (r = 0.9); thus, it is assimilated into Iran's social and cultural conditions (15). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha r = 0.87 was obtained.

3.3. Data Analysis

The collected data were coded and entered into the computer using SPSS version 16 software. After ensuring the accuracy of the data entry, the analysis was performed by the same software. Percentage (frequency) was used to determine the severity and frequency of domestic violence. The ANOVA test, t test and logistic regression was used to analyze the data.

4. Results

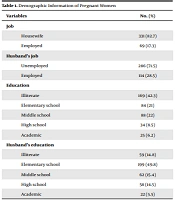

According to data, 17.3% of pregnant women were employed, and 28.5% were illiterate (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Job | |

| Housewife | 331 (82.7) |

| Employed | 69 (17.3) |

| Husband's job | |

| Unemployed | 286 (71.5) |

| Employed | 114 (28.5) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 169 (42.3) |

| Elementary school | 84 (21) |

| Middle school | 88 (22) |

| High school | 34 (8.5) |

| Academic | 25 (6.2) |

| Husband's education | |

| Illiterate | 59 (14.8) |

| Elementary school | 199 (49.8) |

| Middle school | 62 (15.4) |

| High school | 58 (14.5) |

| Academic | 22 (5.5) |

Overall, 3.5% of women experienced very mild violence during pregnancy by their husbands, 13.5% mild violence, and 83% moderate violence (Table 2).

| Violence Types | Severity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very Mild | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Very Severe | |

| Physical | 20 (5.0) | 211 (52.8) | 167 (41.7) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Psychological | 12 (3.0) | 161 (40.2) | 227 (56.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sexual | 266 (66.4) | 131 (32.8) | 3 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Total | 14 (3.5) | 54 (13.5) | 332 (83.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

The total violence mean scores in illiterate and academic pregnant women were 67.4 ± 16.1 and 60.5 ± 10.6, respectively. There was a significant relationship between pregnant women's education and the type of domestic violence (P = 0.028) (Table 3).

| Type of Violence/Education | Mean ± Standard Deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Physiological | Sexual | Total Violence | |

| Illiterate | 35.0 ± 10.1 | 23.3 ± 5.7 | 9.1 ± 5.4 | 67.4 ± 16.1 |

| Elementary school | 31.6 ± 9.2 | 22.7 ± 6.2 | 6.7 ± 4.8 | 61.1 ± 12.9 |

| Middle school | 30.6 ± 6.7 | 24.2 ± 4.9 | 8.7 ± 5.9 | 63.6 ± 9.8 |

| High school | 30.9 ± 8.4 | 22.4 ± 5.7 | 7.1 ± 4.7 | 60.4 ± 12.0 |

| Academic | 30.8 ± 8.9 | 23.4 ± 5.2 | 6.3 ± 4.1 | 60.5 ± 10.6 |

| P | 0.141 | 0.246 | 0.009 | 0.028 |

The total violence mean scores among pregnant women whose husbands had elementary and high school education were 63.7 ± 11.3 and 61.4 ± 12.2, respectively. There was a significant relationship between the type of domestic violence and the husband's education (P = 0.000) (Table 4).

| Type of Violence/Education | Mean ± Standard Deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Physiological | Sexual | Total Violence | |

| Illiterate | 34.1 ± 6.4 | 23.7 ± 5.5 | 7.1 ± 4.2 | 65.1 ± 9.3 |

| Elementary school | 32.8 ± 8.1 | 23.2 ± 5.5 | 6.6 ± 5.1 | 63.7 ± 11.3 |

| Middle school | 30.1 ± 8.6 | 22.3 ± 7.6 | 6.5 ± 5.1 | 55.8 ± 16.7 |

| High school | 27.1 ± 11.2 | 22.7 ± 5.1 | 8.5 ± 6.1 | 61.4 ± 12.2 |

| Academic | 28.6 ± 5.4 | 22.6 ± 4.2 | 5.5 ± 4.7 | 56.9 ± 7.6 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.700 | 0.087 | 0.000 |

The mean scores of total violence were 62.8 ± 12.1 and 58.6 ± 12.5 in participants with a marriage duration of fewer than five years and more than five years, respectively, and the relationship between these two variables was significant (P = 0.006) (Table 5).

| Type of Violence/Education | Mean ± Standard Deviation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Psychological | Sexual | Total Violence | |

| Fewer than 5 years | 31.7 ± 8.7 | 23.4 ± 5.7 | 7.6 ± 5.1 | 62.8 ± 12.1 |

| More than 5 years | 30.1 ± 8.4 | 21.9 ± 5.5 | 6.5 ± 5.4 | 58.6 ± 12.5 |

| P | 0.150 | 0.033 | 0.086 | 0.006 |

The ANOVA test showed the relationship between pregnant women’s and husbands’ education with various types of domestic violence. The t test also showed that there was a significant difference in the type of domestic violence based on duration of marriage. Furthermore, the logistic regression test was used to predict the role of pregnant women and husbands’ education in domestic violence. The significance level was considered P < 0.05. The predictors of domestic violence among pregnant women were the women's education, husband's education, and marriage duration. Thus, the odds of domestic violence were 4.7 times higher in illiterate pregnant women than in women with an academic education (OR = 4.7), which was statistically significant. The chance of domestic violence was 6.2 times higher in pregnant women whose husbands were illiterate than in other pregnant women (OR = 6.2) (Table 6).

| Independent Variables | ß (Regression Coefficient) | S.E. | OR (Odds Ratio) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women's education | ||||

| Academic | - | - | 1 | - |

| High school | 0.49 | 0.51 | 1.1 | 0.41 |

| Middle school | 0.53 | 0.59 | 1.7 | 0.37 |

| Elementary | 1.54 | 0.81 | 3.8 | 0.001 |

| Illiterate | 1.70 | 0.87 | 4.7 | 0.001 |

| Husband's education | ||||

| Academic | - | - | 1 | - |

| High school | -0.031 | 0.64 | 0.97 | 0.96 |

| Middle school | -0.83 | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.17 |

| Elementary | 0.53 | 0.59 | 1.7 | 0.03 |

| Illiterate | 1.8 | 0.91 | 6.2 | 0.001 |

5. Discussion

This study showed that a relatively high rate of women experienced moderate violence during pregnancy. The main reasons for men's violence against women are: Phenomenon of polygamy, early marriage, pre-arranged marriages, women's unemployment, economic dependence on husbands, low literacy, ignorance of women's legal rights. The findings of Parhizkar (16), Hajikhani et al. (17), and Jamshidimanesh et al. (18) were similar to the results of the present study. In contrast, the results of the survey by Behnam et al. (19), Bahri et al. (20), and Naghizadeh et al. (21) did not agree with the results of the present study. Differences in the prevalence of violence among women have been reported, which can be due to research methods, literacy level, sampling type, cultural differences, and the tendency of the respondents to disclose their experiences of domestic violence during pregnancy as part of their private life (19). Some studies suggest that in some cultures, pregnancy is a period in which a woman is more supported by others, including her husband, and therefore the violence rate is reduced (20). Conversely, some theories suggest that because the perpetrator is always in a position of power and control, they may feel that they have less control over the pregnant woman during pregnancy. Also, most women pay attention to their fetus during pregnancy, which makes men jealous, and this jealousy is likely to increase the risk of violence (22). The studies conducted on non-pregnant women also indicate a high prevalence of domestic violence, including the study of Derakhshanpour et al. (23), Delkhosh et al. (24), and Vaseai et al (25). It does not seem to be the case that in some cultures, pregnancy is a protective factor against domestic violence.

In the present study, psychological violence was more prevalent than other types of domestic violence among pregnant women. Psychological violence among pregnant women predisposes them to low self-esteem, depression, and anxiety (26). Women under psychological violence are 3.5 times more likely to fall into the trap of addiction than women without violence (26). According to World Bank studies, mental health problems are the significant cause of years of life lost (YLL) and account for 10.5% of disabilities. This figure is comparable to the incidence of cancer, cardiovascular and cerebral diseases (27). Given the status of women and the dominance of patriarchal culture in which the woman is a weak being, in the absence of the father, the eldest son of the family takes care of the family, and the women are entirely obedient and under the husband command after marriage. Therefore, according to social learning theory, women who have witnessed parental violence in their family or been abused by their parents are more likely to accept violence, including psychological violence from their husbands (12). Also, mental health services and programs are integrated into the health care system, and even at an environmental level of health services (health houses), health workers provide such services to the covered population. But many abused women refuse to go to such centers for fear of losing their reputation and being aware of patriarchal reactions. An essential way to prevent this social and health problem in the long term is to teach life skills, especially by emphasizing communication and education. Life skills training, increasing the level of couples' communication skills, and providing appropriate social support, especially in early life, are effective strategies for reducing the damage caused by psychological violence against pregnant women in the family. Derakhshanpour et al. (23), Bifftu et al. (28), and Sinha et al. (29) reported that the most common type of domestic violence was psychological violence, which is similar to the results of the present study.

Concerning factors related to violence, we found a significant relationship between the pregnant women's and husbands' education and total violence, and the average score of violence increased with decreasing literacy levels. Obviously, with the increase in education, the level of conflicts and disputes decreases (30). In the study of Parhizkar (16) and Behnam et al. (19), the difference between the types of domestic violence and the education of mothers participating in the study was significant, so with increasing the education of the mother, domestic violence decreased. In the study of Fekadu et al. (31), the level of education of the husband was significantly related to psychological and physical violence by the husband, so among the husbands whose level of education was middle school or less, the most reported harassment was psychological and physical, and with the increase of male literacy, its intensity decreases. Shrestha et al. (32) also showed that a high level of male education protects women from violence. This may be because educated people are more aware of the rights and status of women in the family than illiterate people. Other studies have shown that higher education among males reduces spousal violence. For example, research by Aghakhani et al. (33) confirms that a couple's low education is associated with a high percentage of spousal violence, which is similar to the present study's findings.

Other findings of the present study showed that violence was much less among pregnant women who had been married for more than five years than among pregnant women who had been married for less than five years. Behnam et al. (19) and Sadeghi et al. (34) showed similar findings. With the increase in marriage duration, violence decreased, most likely due to the rise in experience and awareness in establishing communication and how to resolve conflicts and disputes.

5.1. Conclusions

Due to the relatively high rate of moderate domestic violence, health promotion interventions such as educating men about various dimensions of violence and its negative impact on the family, creating a culture to strengthen the status and human values of women, and holding training sessions for married men can help reduce this violence during pregnancy. In addition, with increasing literacy levels, the overall score on domestic violence decreased significantly. In explaining the relationship between these variables, it may be said that higher education opens the way to prosperity for family members. By becoming aware of dealing with conflicts in close relationships, educated families downplay domestic violence and take reasonable steps when confronting external or internal barriers.

5.2. Limitations

One of the limitations of the present study was the reluctance to expose domestic violence and the inaccuracy of pregnant women in answering the questionnaire's questions, the control of which was beyond the authority of the researcher. Also, due to the lack of necessary facilities and workforce, it was impossible to investigate violence's effect on pregnancy outcomes. It is recommended to organize training classes for men during marriage and design interventional studies to compare the severity and frequency of domestic violence between the two groups.

.jpeg)