1. Background

Tramadol is a synthetic analog of codeine that comes in various forms, the most popular of which is the oral form (1, 2). This medication relieves moderate to severe pain caused by chronic and incurable diseases, including cancers (3-6). This drug is commonly abused due to its analgesic and euphoric effects and has earned a special place among people. It is sometimes used with other drugs to enhance or replace their effects (5, 7). Tramadol consumption is also common in Iran. A study on the Iranian population showed that pooled estimates of the last 12-month use of tramadol were 4.9% and 0.8% among males and females, respectively (8). The opioid effects of tramadol are caused by interaction with µ receptors, which results in serotonin and norepinephrine effects (9, 10). Although this drug may cause dizziness, imbalance, sleep disturbance, abdominal pain, skin rash, and visual disturbances, drug dependence and seizure are its most severe side effects (1, 9, 11). The incidence of seizures in tramadol abusers is unknown, but various studies have reported that it ranges between 3 and 10% and is more common in young men (4, 12). The most common type of seizure seen in tramadol users is a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, which can be very long and frequent, causing irreversible side effects (6, 9, 12-14). These clinical symptoms, such as electroencephalography, are linked to electrophysiological changes (15, 16).

2. Objectives

Considering the above and the limitations of the electroencephalogram findings, this study investigated the frequency of seizures caused by tramadol abuse and electroencephalogram (EEG) findings in patients with seizures admitted to the Shafa Hospital in Kerman City.

3. Patients and Methods

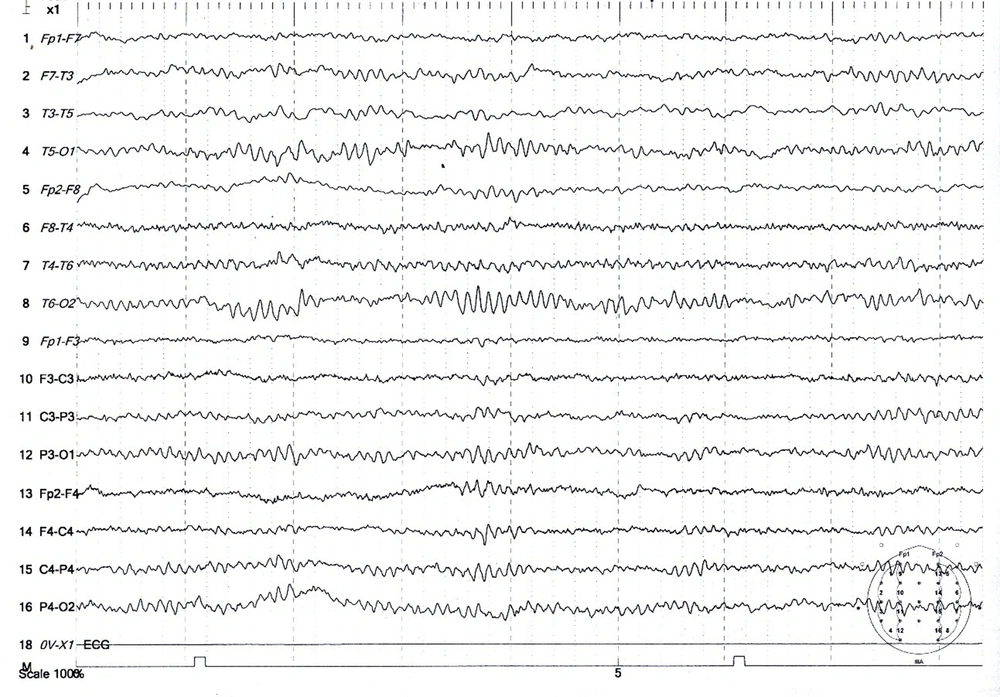

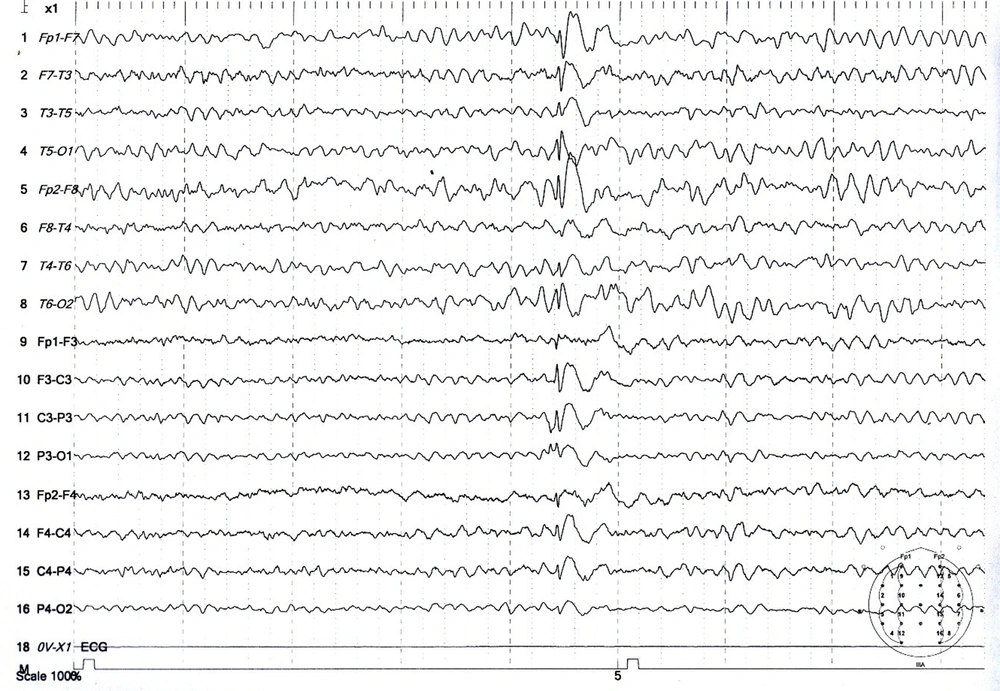

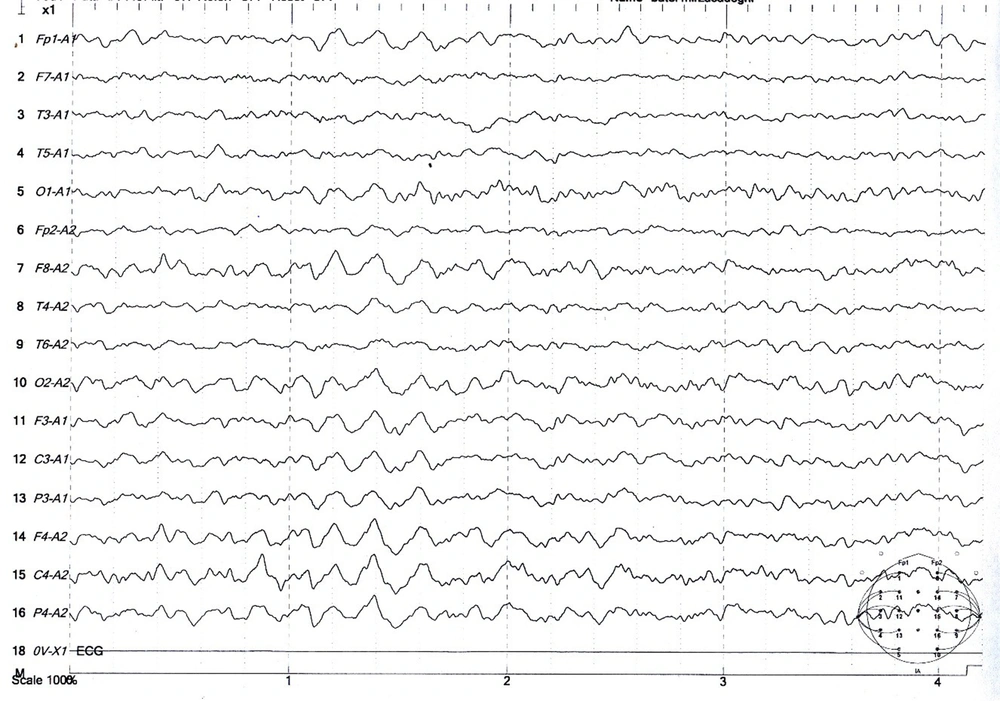

The population was patients with tonic-clonic seizures admitted to the Shafa Hospital in Kerman City from April 2017 to March 2017. At admission, all patients had a full medical history taken. In addition to the systemic and neurological examinations, metabolic evaluations were performed, and the patients underwent a contrast-free brain CT scan in case of normality of these evaluations. Patients with signs of a disorder in any of the above evaluations were excluded. Also, patients with a history of medication and drug abuse other than tramadol or underlying diseases such as epilepsy, trauma, or alcohol consumption were excluded. Then, for each patient, a checklist of information was completed, including age, gender, marital status, education, occupation, history of seizures associated with tramadol consumption, tramadol dose, tramadol duration, the interval between tramadol consumption and seizures, and the number of seizures. Electroencephalogram was performed between the third and fifth day using a Negarandishegan 3520 electroencephalography. All EEGs were done in an awake state for 20 minutes with at least one monopolar assembly and four bipolar assemblies. A single-blind person interpreted the EEGs. This study was approved by the University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee under the code IR.KMU.AH.REC.1398.203, and patient information was kept confidential. SPSS 20 was used to analyze the data obtained from this study. Mean, standard deviation, and percentage were used for descriptive data, while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for analytical data. The significance level was 0.05 (Figures 1 - 3).

4. Results

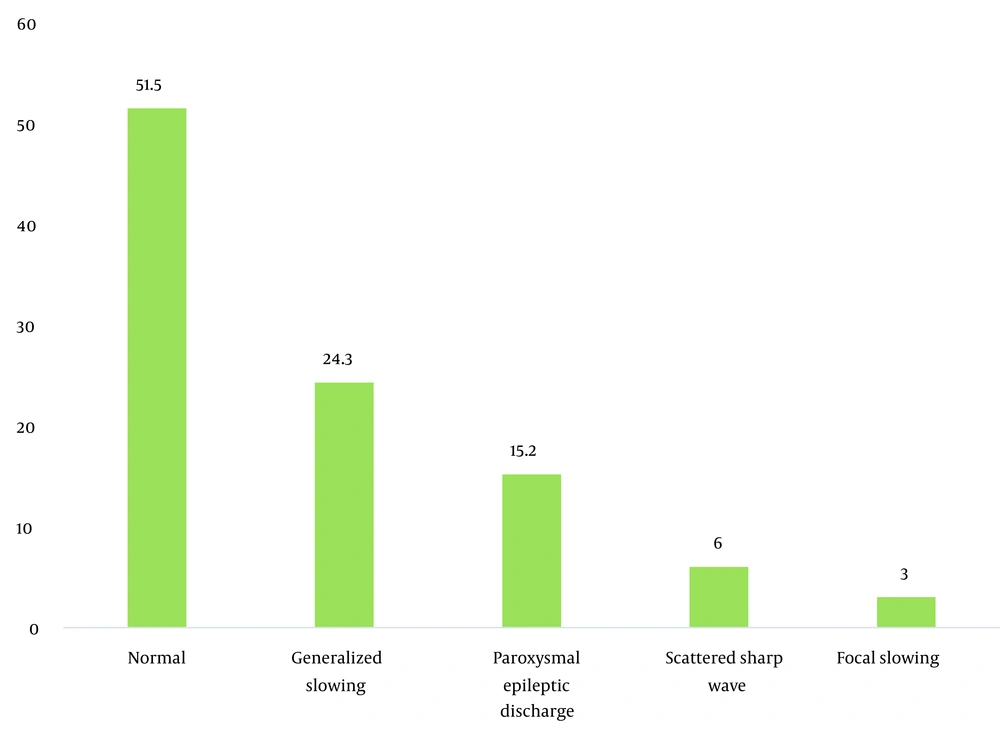

During the study period, 356 patients with seizures were admitted to the Shafa Hospital. The initial diagnosis showed that 12.9% (46) of the patients had tramadol abuse seizures. Among them, 33 patients (9.3%) with tramadol abuse seizures followed the study protocol completely, and 13 patients were excluded because they showed abnormality in the neurological examination, metabolic evaluation, or non-contrast CT scan. The age range was 17 to 55 years, with a mean age of 29.96 ± 9.93 years. The majority of the patients (72.7%) were male. The characteristics of the patients studied are shown in Table 1. The average tramadol dosage was 111.73 mg with a standard deviation of 71.43, the average duration of consumption was 11.75 months with a standard deviation of 6.29, the average time interval between consumption and seizures was 11.45 hours with a standard deviation of 7.25, and the average number of seizures was 2.31 times with a standard deviation of 1.40. A total of 24 patients (72.8%) had a single seizure. In this study, seven patients (21.21%) had seizures between 1 to 7 days of tramadol abuse, and 26 patients (78.78%) had seizures less than 24 hours after consumption. Also, 48.5% of the patients had an abnormality in the electroencephalogram. The mean dosage of tramadol in patients with abnormal EEG (143.0 69 ± 22.69 mg) was significantly higher than in patients with normal EEG (84.37 ± 10.91 mg) (P = 0.02). Furthermore, changes in the electroencephalogram were related to the duration of tramadol consumption (P = 0.002) and the time interval between tramadol consumption and the occurrence of seizures (P = 0.001). The frequency of EEG changes in patients with an initial diagnosis of tramadol abuse seizures is shown in Table 2. The most observed abnormality was diffuse slowing (24.2%). In the case of focal slowing, a brain MRI was performed with the epilepsy protocol, which revealed no anatomical lesion (Figure 4).

| Variable | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 24 (72.7) |

| Female | 9 (27.3) |

| Age (y) | |

| ≤ 40 | 27 (84.5) |

| > 40 | 5 (15.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 18 (54.5) |

| Married | 15 (45.5) |

| Education | |

| Literate | 27 (84.8) |

| Illiterate | 5 (15.2) |

| History of seizure due to tramadol abuse | 6 (18.2) |

| Electroencephalogram abnormality | 16 (48.5) |

Demographic Data of Patients with Tramadol Abuse Seizures

| Electroencephalogram | Mean ± SD | P |

|---|---|---|

| Tramadol dosage (mg) | 0.02 | |

| Normal | 84.37 ± 10.91 | |

| Abnormal | 143.00 ± 22.96 | |

| Duration of tramadol usage (y) | 0.002 | |

| Normal | 3.12 ± 0.93 | |

| Abnormal | 21.53 ± 5.02 | |

| Time of seizure | 0.001 | |

| Normal | 6.11 ± 1.02 | |

| Abnormal | 17.12 ± 2.94 | |

| Number of seizures | 0.27 | |

| Normal | 2.56 ± 1.43 | |

| Abnormal | 2.06 ± 0.67 |

Comparison Means of Tramadol Abuse Features Based on Electroencephalogram Findings

5. Discussion

This study evaluated the frequency of patients with seizures due to tramadol abuse and EEG findings. According to our findings, approximately 10% of patients had tramadol abuse seizures. This finding is similar to those of other studies. For example, in Egypt, Shamloul et al. found that 7% of patients had tramadol abuse seizures (12). In a cross-sectional study conducted in Tehran, 14.5% of tramadol overdose patients had seizures (9). Studies in the United States reported 52.5% of tramadol overdoses (17). Tramadol consumption appears to be associated with a 41% increased risk of seizure (18). In a review article, Nakhaee et al. found that the seizure event rate was 3% in therapeutic dosages of tramadol, 38% in tramadol poisoning, and 37% in tramadol abusers (5). According to the findings of another systematic review study published in Iran in 2020, the overall estimate of seizure in tramadol poisoning was 34.6% (8). These statistical differences are primarily due to differences in the sample population, although other factors, such as race, might be important. For example, research has shown that tramadol-induced seizure was more common among Asians (17). Most consumers in this study were under 40 years of age, similar to other studies (4, 12), although some studies have shown that tramadol consumption is not related to age (17). This finding heightens concerns about young people’s involvement in our society. Our findings also revealed that seizures were more common in men than in women. This finding can be found in most studies (5, 9, 12, 19, 20). Regardless of physiological differences between sexes, differences in the amount or duration of consumption between sexes may influence the occurrence of this finding, as some studies show that seizures are directly related to tramadol dosage (5, 14). At the same time, studies show that the frequency of seizures is not dosage-dependent (9, 19, 21). Consumption and the occurrence of seizures were found to be higher in educated patients in this study. We did not have a study to compare, but this finding indicates that people with an academic education are also afflicted by this problem. In this study, married people were almost as involved as single people, indicating the extent of social harms related to tramadol abuse and that marriage could not protect against this high-risk behavior. This study found that approximately 18% of the participants had a history of tramadol-related seizures, which is higher than that in previous studies (18). This finding suggests that patients with primary seizures do not receive adequate follow-up or education about tramadol and its recurring side effects. In addition, 72.8% of the patients in this study had single seizures, similar to other studies (18). In the study conducted by Farajidana et al., 89.2% had a single seizure, 9.1% had a double seizure, and only 1.7% had a seizure more than twice (13). In another study in Iran, only 7% had recurrent seizures (22). In our study, 78.78% of the patients experienced seizures less than 24 hours after consumption, which is consistent with most studies, indicating a peak time for seizures (8). The mechanism of seizure in tramadol abusers is not fully understood, but this drug produces seizure through inhibition of nitric oxide, serotonin reuptake, and inhibitory effects on GABA receptors (2, 18, 22-24). In this study, more than half of the cases had EEG abnormalities, although epileptic waves were seen in only about 20% of the patients. There have been few studies on EEG changes in tramadol users. In a cross-sectional study, 87.5% of subjects had normal inter-ictal EEG (12). Another cross-sectional study discovered that 43% of tramadol customers had EEG changes on the first day, but the abnormality was only 3.5% a week later in the control EEG (25). Our findings revealed that abnormalities in the EEG were affected by dosage, duration of consumption, and the time interval between consumption and the occurrence of seizures. Although we did not have a comparable human article, animal studies show that tramadol can cause seizures at all doses (26). Our study also had some limitations. First, other types of seizures were not evaluated, although, according to the published articles, most seizures caused by tramadol are generalized tonic-clonic (12). Second, patients in this study only had one EEG. Repetition of EEG can provide a more accurate assessment of the electrophysiology of the changes.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study found that approximately 10% of patients had tramadol abuse seizures, with young men being at a higher risk. Electroencephalogram abnormalities in more than half of people indicate the importance of electrophysiological changes.