1. Context

The transition from childhood to adolescence is marked by biological, psychological, and social changes. This growth stage is characterized by experimentation, exploration, and risk-taking (1). In this stage, individuals start to complete their sexual development (2). However, sexual development does not occur in a vacuum, and the social context and interpersonal relationships significantly influence how individuals develop their sexuality (3). In some social contexts, the prerequisite of healthy psychological growth is to postpone sexual activities until marriage (4). Nevertheless, this expectation does not practically oblige people to act like that. Much research shows that individuals begin to have sexual relationships at an early age (5), bringing about many potential risks for them (6). Individuals have their first sexual intercourse at this stage and are exposed to many sexually transmitted diseases (5).

Knowing the cause of such behaviors is essential to protect individuals from potential risks. To make an appropriate decision on the causes and prevention methods of high-risk sexual behaviors, therapists and researchers need to weigh the existing literature. One of the methods of weighing the existing literature is to do a systematic review. Therapists who want to be up-to-date in their field consider systematic reviews as the starting point of their clinical guidelines (7). Therefore, the importance of systematic review and meta-analysis is growing increasingly. Policy-makers and practitioners need practical recommendations to plan efficiently. Considering the extent of this field, we need studies that present suggestions beyond simple advice. The present paper contributes to this field from different aspects. First, it conducts a comprehensive and up-to-date evaluation of the causes of high-risk sexual behaviors and then tries to answer some questions: What are the risk factors for performing high-risk sexual behaviors? What are protective factors? What kind of training was conducted to take care of people?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Selection

The present paper deals with the systematic review of protective and risk factors of high-risk sexual behaviors. The PRISMA protocol suggested by (7) was used to review the published articles. The studies were identified in several ways: Looking for studies published in recent years, searching for the keywords of high-risk sexual behaviors, including sex education, comprehensive sex education, sexual, psychological development, and abstinence, and searching for articles presented in scientific conferences. Most of these searches were done in the databases SAGE, Wiley, Science Direct, Taylor & Francis Group, SID, and Google Scholar.

2.2. Data Extraction

Among the studies published from 2000 to 2021 on high-risk sexual behaviors, the ones with participants under 25 years of age were selected. If a participant's age was more than 25, they were excluded to avoid distorting the findings. For this reason, studies on adulthood were excluded. High-risk behaviors like dangerous driving or physical injuries were defined as violent behaviors, and the related papers were excluded from the study. Papers on violent acts associated with carrying weapons and physical violence were also eliminated. Intrapsychic behaviors were considered personality problems, and the data were also excluded. The researchers used articles published in Persian and English because using studies published in other languages would have led to translation complications. Studies investigating high-risk behaviors caused by specific disorders, such as hypersexual desire, were also eliminated.

The researchers did not consider any geographic restriction. The data were extracted using a standard form that examined the characteristics of each study as sample size, age range, country, research design, moderating variables, confidence interval, beta coefficient, and standard error. In cases of similar articles, the one with a larger effect size, a larger sample, or more than two variables was selected. Two reviewers independently reviewed these items. The relevance of the articles and the decision to do the final review process were confirmed by the agreement between the evaluators (k = 0.77). In cases of any disagreement, they consulted another author.

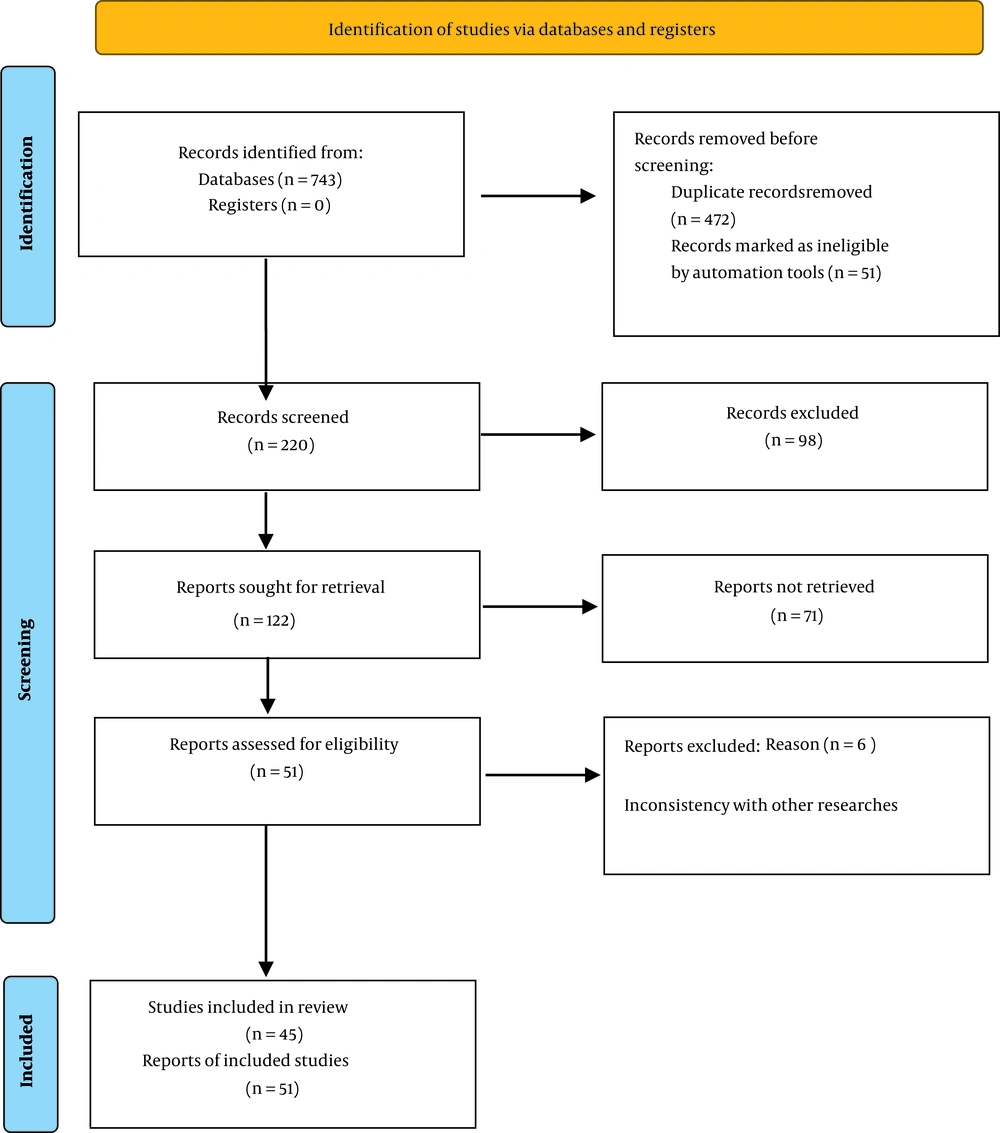

The screening process included two stages. At first, the abstracts and titles of the articles were screened by studying the research literature. At this stage, 743 titles were identified. The author assessed all studies and excluded duplicates and completely irrelevant studies. Hence, the researchers eliminated 472 studies, and 51 were identified as duplicates by the EndNote software. Subsequently, the two authors independently reviewed the remaining studies. Then, the text of the articles was examined. Several criteria were considered for the eligibility of studies. First, the article should have addressed risky sexual behaviors. Second, the research should have addressed young people under 25. After reading the text of the articles, 220 articles remained. Ninety-eight articles were excluded from the review due to not meeting the standards. Also, 71 other studies were excluded due to low quality. Six other ones were excluded due to inconsistency with other studies.

Accordingly, a total of 45 articles were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). Six articles dealt with both protective and risky behaviors. That is why they are repeated in both tables. Since there is a risk of bias in the systematic review at the study and outcome levels, two independent coders coded the articles to reduce the bias risk. The final articles were approved by the third coder (supervisor). Since the researchers may spontaneously refer to some findings and ignore some, they discussed the findings with each other to assess the accuracy of the estimates.

3. Results

After reviewing the papers published since 2000, 45 articles were analyzed. The studies of Rogers et al. (8), Castro (9), Manlove et al. (10), Aspie et al. (11), Holder et al. (12), and Dittus and Jaccard (13) addressed both risk factors and protective factors, so they are reported in both tables. The number of studies mentioned in the tables is 51, which is reduced to 45 by deducting the six studies repeated above. These papers identified and investigated the high-risk factors in 25 articles with a sample size of 67,783 (Table 1) and protective factors in 26 articles with a sample size of 72,487 (Table 2).

| Main Factors | Secondary Factors | References |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Watching pornographic videos | Efrati & Amichai-Hamburger (14) |

| Being the victim of sexual abuse | Tang et al. (15) | |

| Online sexual activities | Efrati & Gola (16) | |

| Sexual curiosity | Ševčíková et al. (17) | |

| Negative sexual self-concept | Lacelle et al. (18) | |

| Low self-esteem | Lacelle et al. (18) | |

| Reduction of risk perception during intercourse | Castro (9) | |

| Perception of anonymity in online sexual activities | Efrati & Gola (16) | |

| Alcohol consumption | Stoner et al. (19) | |

| Loneliness | Bothe et al. (20) | |

| Emotional problems | Howard & Wang (21) | |

| Sensitivity to rejection | Woerner et al. (22) | |

| Family | Father's use of drugs, alcohol, and cigarettes | DelPriore et al. (23) |

| Weak family foundation | Steele et al. (24), Rezazadeh et al. (25), Ahmadi et al. (26) | |

| Divorce of parents | Steele et al. (24) | |

| Living with a single parent | Steele et al.(24), Aspy et al. (11), Dittus & Jaccard (13), Rezazadeh et al. (25) | |

| Parents' extramarital affairs | Steele et al. (24) | |

| Parental violence | Neppl et al. (27), Rezazadeh et al. (25) | |

| Conflict between parents | Fomby et al. (28) | |

| Mother's remarriage | Beck et al. (29) | |

| Domestic abuse | van Roode et al. (30) | |

| Childhood abuse | Negriff et al. (31) | |

| Romantic dates of single mothers | Steele et al. (24), Fomby et al. (28) | |

| Social | Lack of proper education | Rogers et al. (8) |

| Escape from social exclusion | Woerner et al. (22), Iffland et al. (32) | |

| inefficient social support | Mazzaferro et al. (33) | |

| Peers who have experienced risky sexual behavior | Roberts et al. (34) | |

| Inadequate and inappropriate social ties | Efrati & Amichai-Hamburger (14) | |

| Spiritual | Weak religious beliefs | Holder et al. (12) |

| Failure to adhere to religious values | Manlove et al. (10) |

| Main Factors | Secondary Factors | References |

|---|---|---|

| Individual | Participation in productive economic activities | Darteh et al. (35) |

| Health literacy | Darteh et al. (35) | |

| Saying no to sexual requests | Aspy et al. (11) | |

| Family | Caregiving role of parents | Haglund & Fehring (36), Longmore et al. (37) |

| Living with both parents | Aspy et al. (11) | |

| Feeling close to parents | Longmore et al. (37) | |

| Disapproval of sexual relations by the family | Dittus & Jaccard (13) | |

| High levels of parental supervision combined with supportive and loving interactions | Lansford et al. (38) | |

| Informing parents about the location of children | de Graaf et al. (39), de Graaf et al. (40) | |

| Parental support and knowledge of sexual issues and safe sexual behaviors | Coakley et al. (41), de Graaf et al. (39), de Graaf et al. (40) | |

| Authoritative parenting | Landor et al. (42), Simons et al. (43) | |

| High-quality parent-child relationship | Rogers et al. (8) | |

| Effective and adequate communication with parents | Holman & Kellas (44) | |

| Effective education about sexual risks by parents | Evans et al. (45) | |

| Parents talking to children about sex | Holman & Kellas (44), Evans et al. (45), Aspy et al. (11) | |

| Family-based education | Murry et al. (46) | |

| Social | Educational and preventive programs | Castro (9), Lindberg & Maddow-Zimet (47) |

| Sex education in school | Kim et al. (48) | |

| Educational interventions based on knowledge enhancement | Ma et al. (49), Basta et al. (50) | |

| Education without the feeling of fear and shame | Hoefer & Hoefer (4), Ssebunya et al. (51) | |

| Spiritual | Participation in religious activities | Holder et al. (12) |

| Being in an appropriate environment | Manlove et al. (10) | |

| Religious attitudes | Haglund & Fehring (36) | |

| Parents' religiosity | Landor et al. (42) |

3.1. Individuals Factors

Watching pornographic films (14), being a victim of sexual abuse (15), online sexual activities (16), sexual curiosity (17), negative sexual self-concept (18), low self-esteem (18), reduction of risk perception during sexual intercourse (9), the perception of anonymity in online sexual activities (16), alcohol consumption (19), loneliness (20), emotional problems (21), and sensitivity to rejection (22) were identified as risk factors. On the other hand, being active and participating in productive economic activities (35), saying no to sexual requests (11), and health literacy (35) were considered protective factors.

3.2. Family Factors

Using drugs and alcohol by fathers (23), weak family foundation (25), parents' divorce (25), living with a single parent (11, 13), parents' extramarital affairs (25), parents' violence (27), conflict between parents (28), mother's remarriage (29), abuse in the family (30), childhood misbehavior (31), and romantic dating of single parents (25, 28) put people at the risk of engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors. On the other hand, parental caring role (36, 37), living with both parents (11), feeling close to parents (37), parental disapproval of sexual relations (13), high level of parental supervision along with supportive communications (38), parents' awareness about children's location (39), support and knowledge of parents about sexual issues and safe sexual behaviors (39, 41), authoritative parenting (42, 43), quality of parent-child relationship (8), effective and sufficient communication between parents (44), effective education of sexual risks (25, 26), parent-child conversation about sex (11, 26, 44), and family-based education (46) were effective actions in protecting children against high-risk sexual behaviors.

3.3. Social Factors

Lack of proper education (8), escape from exclusion (22, 32), inefficient social support (33), having friends with experience of risky sexual behavior (34), and insufficient and inappropriate social ties (14) make people susceptible to high-risk sexual behaviors. However, educational and protective programs (9, 47), sex education in school (48), educational interventions based on increasing knowledge (49, 50), and education without the feeling guilt and shame (4, 51) protect people from risky sexual behavior.

3.4. Spiritual Factors

Weak religious beliefs (12) and non-adherence to religious values (10) form the basis for the occurrence of risky sexual behaviors. However, participation in religious activities (10), having strong faith (10), religious attitudes (24, 36), and faithful parents (42) protect people from danger.

4. Discussion

This systematic review is a comprehensive and up-to-date assessment of the causes of high-risk behaviors and protective factors against them. To do the assessment, we identified 743 papers published from 2000 to 2021. After investigating the titles, abstracts, and standards based on the systematic review format suggested by Moher et al., 45 articles remained for the final analysis (7). The results were categorized into individual, family, social, and spiritual categories.

Individual factors have been defined, measured, and operationalized differently in different papers among the most critical protective and risky factors. For example, Castro (9) focused on reducing risk perception during the relationship. However, Woerner et al. focused on the sensitivity to rejection (22). In any case, regardless of the definition and measurement of individual variables, they affect the occurrence of high-risk sexual behaviors (16, 20). Considering the sensitivity to rejection, contexts peers are involved in seem to worsen the issue. Such situations make people vulnerable to high-risk behaviors by provoking emotional and physiological reactions (22). Although some studies associate this rejection with emotionally and physically invalidating experiences in childhood (9), others state that it is the result of the lack of sexual assertiveness (11).

Identity issues and engaging in risky sexual behaviors were the common findings of all studies. However, the studies merely focused on emotional and physiological reactions and did not suggest any recommendations about how a person should deal with social rejection, and emotional issues as an individual component have enough scientific and research evidence. This can be considered a significant growth factor in people's growth process. This factor was also defined, measured, and operationalized with different methods in different studies. For example, some studies defined emotional invalidation as sexual abuse in childhood (18). Some defined it as negligence (15), and others defined it as physical violence (27). These developmental experiences could include the divorce of parents in childhood, which was mentioned in few studies (25). These studies focused on negative childhood experiences' role in regulating emotions. However, nothing was mentioned about how this emotional regulation prevents a person from risky behaviors.

Sexual curiosity was also considered an essential factor. At the beginning of the activation of sexual desire, people generally look for those sexual relationships that require no obvious commitment. First, they use online and offline channels for sexual activities and prepare themselves for physical intercourse. Digital channels create a safe margin to satisfy their curiosity and access to sexual stimuli, leading them to perform physical sexual behaviors. Individuals start with a tentative sexual image of themselves and then move on to real relationships. In this regard, some research reveals that when individuals start sexual curiosity at an early age, they seek more sexual excitement when they get older (17). Studies do not provide anything about the situations in which sexual curiosity is considered inappropriate or normal or the age at which it is normal. But it seems that to channel this curiosity toward natural age-appropriate behaviors, we need more research to make a better decision.

The reduction of risk perception during intercourse has also been reported as a risk factor in studies. The study by Castro showed that among 1,452 university students, 87% experienced vaginal penetration, and 20% experienced anal intercourse. In addition, in both cases, reluctance to use preventive measures and drug and alcohol consumption were also observed. A significant majority of these people had experienced cases of sexually transmitted infections and sexual problems. Such infections were investigated in different studies. Some researchers examined people's blood in a laboratory, and others used questionnaires (9). Castro used a university laboratory and found that some of these people were unaware of their infection and that it could be transmitted to others. However, the studies did not say anything about the reason for students' risky behavior and reluctance to use preventive measures, despite being educated and informed. Another study stated that being employed and participating in productive economic activities is an essential barrier against risky sexual behaviors (35). Nevertheless, we still need more research to conclude in this area. Studies must also consider other factors because being active in society can facilitate communication and access to sexual partners. The studies do not present information about which jobs act as obstacles, whether people voluntarily delay this action, or whether this issue is one of their job requirements.

Another critical factor was low self-esteem and negative sexual self-concept. In this regard, Lacelle et al. showed that low self-esteem and inappropriate sexual self-concept are among the causes of high-risk sexual behaviors (18). Studies revealed that low self-esteem causes emotional problems in people and leads to loneliness (20). Loneliness makes people vulnerable and susceptible to risky sexual behavior. If we consider emotional problems and loneliness as the result of low self-esteem and inappropriate sexual self-concept, then it is likely that these people engage in online sexual activities or alcohol consumption (16, 19). Again, no specific suggestion was given on how to deal with loneliness. However, in the studies that pointed to the protective role of individual factors, the role of health literacy was emphasized. For example, in Darteh et al, health literacy was considered a protective factor (35). Also, Aspy al. mentioned that "saying no," as one of the components of health literacy, can protect people from such behaviors (11). However, there is no consensus on whether assertiveness causes people to say no or whether their personality traits make them assertive. In any case, more studies are needed to decide on this field.

Family factors are also considered both protective and risky factors in the occurrence of high-risk sexual behaviors. In the studies, a strong family foundation was a powerful shield against risky sexual behaviors. However, there were many differences in the methods of measurement and definition. Inconsistencies were also observed in the quality of measurements. Regarding the sub-components of the family foundation, it seems that parent-child dialogue in a safe environment positively affects managing risky sexual behaviors. This is a significant factor not seen in dysfunctional families (25). When family members perceive high levels of family bonding, the effect of parental monitoring on sexual behaviors increases because children better accept such parental monitoring. This can be part of an authoritative parenting strategy. Therefore, studies consider the relationship between parents and children as an essential care factor in preventing high-risk behaviors (11). Supportive behaviors provided by parents create a sense of belonging and positively impact children's sexual relationships. Of course, the research emphasizes improving communication and sexual assertiveness skills in the family because early, and multiple sexual experiences become the basis for later adulthood behaviors (9).

Regarding the optimal family foundation, studies reveal similar results. Dysfunctional families were considered one of the essential factors in high-risk sexual behaviors. For example, living with a single parent and single-parent dating are essential factors in the occurrence of high-risk sexual behaviors (25). As mentioned before, there is little supervision over children's behavior in such families, and they hardly accept it, especially when they see parents dating. On the other hand, excessive parental control can also lead to the risk of sexual behaviors. Although research findings showed that risky sexual behaviors are related to the parent-child relationship, this issue is not considered in dysfunctional families (23, 28). In such families, there is no agreement on child-rearing and parenting issues. Studies have thoroughly investigated this issue and provided strong evidence.

Social factors can also be important in the occurrence and prevention of high-risk sexual behaviors. For example, lack of proper education, inefficient social support, and having friends with risky sexual behavior was regarded as social factors. Even though these social factors make people vulnerable to risky sexual behavior, social protective factors emphasize sex education and health literacy. We can define health literacy as the degree to which individuals can obtain, process, and understand basic health information needed to make appropriate health decisions (35). Therefore, access to education and health literacy is considered one of the critical protective factors. Studies in this field emphasize such access in the family, school, and society. Programs considering the relationship between families and teenage members reported that parents' actions had a positive effect. For example, in an educational program aimed at youth development and educating parents about positive parenting methods, effective communication and active participation in sex education were proven to have positive impacts (32). Other programs used role-playing strategies to strengthen parent-child social and sexual communication. Spending time with peers who are responsible and sociable can have a positive effect on sexual relationships. However, studies did not mention how we can access proper education, and it seems we face limitations in obtaining this information. In any case, changes in school policy and interactive classroom education can lead to managing these behaviors. However, we need interventional research in this field because cultural sensitivities are essential to this factor.

Finally, the spiritual factor is an important protective factor. Studies reported that being in contexts that do not support religious beliefs is a risk factor. However, people who were faithful or those whose parents had religious beliefs were reported to be safe from sexually risky behaviors. Studies used several methods in defining religion, which naturally affected measuring religious attitudes. However, research reported that religion is a decisive factor in preventing risky sexual behaviors (24, 36, 42, 45).

To sum up, it seems that the factors investigated in the studies interact with each other. Therefore, the joint actions of families, schools, and society can effectively deal with such behaviors. These steps should be made to protect future generations as a social resource. But to achieve this, we must first become more knowledgeable in this area and be aware of the problems and cultural sensitivities in treatment and prevention strategies. Furthermore, it is critical to realize that these behaviors evolve naturally as children grow, and on the other hand, young people are becoming more independent and experienced. Therefore, looking at all age groupings over time is essential to understand their contexts, circumstances, communication needs, and care requirements.