1. Background

A fundamental question in addiction tendency is which factors propel people toward substance use. Various studies found that unsafe fields of interest are a criterion for the adoption of substance use. Addicts are people with unsafe development in various areas that propel them toward substance use; the development of a tendency toward substance misuse over a person’s lifetime is considered addiction talent (1).

According to many models of substance abuse, family factors are among the main variables affecting substance use, of which the mode of upbringing of children and parenting styles are considered the most important (2). For example, rejection and overprotective (3) and neglectful parenting can predict risky behaviors and the development of psychological non-adaptive behavior, such as substance use, in adolescents (4). The process by which parental rearing of children may predispose individuals to addiction is a matter of controversy. Research that evaluates the role of intervariable mediators is throwing up some ideas. For example, several studies have investigated the relationship between parental rearing and novelty as one of the variables to be considered at the beginning of substance use. A similar amount of variance concerning temperamental traits seems to depend on non-shared environmental influences, among which parenting styles have to be taken into account (5). There is an inverse relationship between novelty seeking and parental warmth (6). A high level of novelty seeking among child abusers and rape offenders is reportedly related to maltreatment by authoritarian parents (7). Poor parental care and greater parental interference are related to high levels of novelty seeking and low harm avoidance (8). An authoritative parenting style, with its effect on sensation seeking (which is a novelty-seeking component), can play a protective role in the relationship between sensation seeking and a tendency to use marijuana and succumb to peer influence (9). Given that individuals with high novelty-seeking tendencies have difficulty in delaying gratification, they equally have difficulty in adapting to the demands of others, especially parents and peers; therefore, they are more likely to develop behavioral problems and engage in substance use (10). Several studies also confirm that novelty seeking is a predictor of externalizing behavioral problems (11). There is a direct relationship between high novelty seeking and low harm avoidance with externalizing behavioral problems (12, 13).

Further, several studies have demonstrated the relationship between externalizing behavioral problems and substance use. Behavioral problems are related to the early appearance of problems due to drug abuse (14). Korhonen et al. showed that behavioral problems and smoking can be a predictor of cocaine use (15). In a longitudinal study over three generations, it was found that externalizing behavioral problems in adolescence predict substance use in adulthood (16). On the other hand, it has been found that there is a direct relationship between parenting styles and behavioral problems. Harsh and contradictory parenting styles such as poor monitoring and permissive control were related to aggressiveness, behavioral problems, and criminality (17). There is a positive relationship between a violent upbringing and behavioral problems, and an authoritarian parenting style appears to cause resentment and externalizing problems in adolescents (18). Conversely, there is a positive correlation between maternal physical affection and children's social competence and self-control (19). Parents’ stable behavioral control is associated with lower levels of externalizing problems in adolescents (20).

Children who live in surroundings where there are conflicts, little expression of positive emotions, and no proper model of positive behavior or modeling of ways to adjust one’s emotions often fail to develop coping strategies to enable their own emotional regulation (21). Parenting can thus be responsible for adolescent psychological conditions that develop along both positive and negative paths (22, 23).

Numerous studies have reported the relationship between coping strategies and behavioral problems (24, 25). An inverse relationship is reported between a problem-solving coping style and behavioral problems in preschool children, manifesting itself in externalizing behavioral problems such as hyperactivity and attention deficit disorder and aggressive and destructive behavior (24). In another study, a negative relationship was reported between an emotion-oriented coping strategy (as an adaptive strategy) and emotional and behavioral problems (25). Studies also suggest an association between coping strategies and substance use; most researchers have emphasized the usefulness of a problem-oriented strategy as a protective factor against substance use (26, 27). The lack of adaptive coping skills and insecure attachment, especially among girls who always keep a psychological distance from others, may encourage substance use, independently and collaboratively. Therefore, effective coping strategies are considered as protective factors and ineffective coping strategies are considered as risk factors for substance use (28-30).

2. Objectives

In addition to identifying risk and protective factors, this study develops and examines a model that encompasses the variables of novelty seeking, behavioral problems, and coping strategies as mediators of parenting styles and addiction potential.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Subjects

The present study consisted of male and female students in the third grade at public high schools in Mashhad, Iran, in 2011/12.

Sampling Method: In this study, two separate samples were selected, using a multi-stage random sampling method for hypothesis testing [572 students, including 328 (57%) boys and 244 (43%) girls, mean age 17] and to assess the psychometric properties of the research questionnaires [48 students, including 22 (46%) girls and 26 (54%) boys, mean age 17].

3.2. Research Tools

In order to measure the variables, the following tools were used in this study.

1. Iranian addiction potential scale: This scale consists of 36 items, 5 lie detectors, and 2 passive and active potential factors. In this study, its reliability in assessing addiction potential was calculated at 0.70 using Cronbach’s alpha; its validity was rated at 0.39, which was significant (P = 0.006).

2. Cloninger Temperament and Character Inventory: To measure novelty seeking, a short form of the Cloninger Temperament and Character Inventory was used. Its reliability using Cronbach’s alpha in novelty seeking was computed at 0.71 and its validity at 0.33 (P = 0.005).

3. Parenting Styles Questionnaire: In order to assess parenting styles, the Baumrind Parenting Style Questionnaire was used. This questionnaire measures three parenting styles, namely permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian styles (29). In the study, its reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha) in regard to permissive, authoritative, and authoritarian styles, respectively, was 0.81, 0.75, and 0.69; also, its validity in the authoritative parenting style was measured at 0.70 (P = 0.001, significant), in the authoritarian parenting style at 0.63 (P = 0.001, significant), and in the permissive parenting style at 0.53 (P = 0.001, significant).

4. Achenbach Youth Self-report Scale: To measure behavioral problems, the Achenbach youth self-report scale was used. Its reliability using Cronbach’s alpha was found to be 0.66 to 0.85. Its validity was calculated at 0.62, 0.34, 0.50, and 0.47 (P = 0.001, significant).

5. Coping inventory for stressful situations: To assess coping strategies, the Endler and Parker coping inventory for stressful situations was used. This test consists of three styles of coping, namely problem-oriented, emotion-oriented, and avoidance-oriented (30). This questionnaire has good reliability and validity. Reliability using Cronbach’s alpha in the present study ranged from 0.78 to 0.84 and convergent validity of this scale through correlation of the questionnaire with the dimension of neuroticism and extraversion of the NEO-questionnaire was evaluated, revealing a significant relationship between problem-focused and emotion-focused coping strategy with neuroticism, at the 0.01 level (-0.34 and 0.48), respectively.

3.3. Methods of Data Analysis

Statistical methods for data analysis are: 1) descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, and correlations between variables; 2) structural equation modeling. All analyses were performed using SPSS-16 and AMOS-16 software. To determine the fitness adequacy of the proposed model with data, a combination of fitness indices including the Chi-square (χ2), the ratio df / χ2, GFI (goodness of fit index), AGFI (adjusted goodness of fit index), CFI (comparative fitness index), IFI (incremental fitness index), and TLI (Tucker-Louise index), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the normed fitness index (NFI) were used (31).

Finally, to test the indirect effects of coefficients with two mediator variables or chain mediation in the model, the Bootstrap test model was used (32). The significance of the research hypothesis was placed at the 0.05 alpha level.

4. Results

Table 1 shows that the highest percentage was recorded for fathers and mothers who graduated with a diploma (32.5), whereas the lowest percentages were recorded for those fathers who had a doctoral degree (0.5) and mothers who were illiterate (0.02).

| Mother’s Education | Father’s Education | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illiterate | Primary | Guidance | Diploma | Associate | BS | BA | Doctorial | Unknown | Illiterate | Primary | Guidance | Diploma | Associate | BS | BA | Doctorial | Unknown | |

| Number | 1 | 17 | 114 | 323 | 37 | 40 | 6 | 2 | 32 | 7 | 97 | 124 | 186 | 34 | 61 | 24 | 3 | 36 |

| Percent | 0.2 | 3 | 19.9 | 56.5 | 6.5 | 7 | 1 | 0.3 | 5.6 | 1.2 | 17 | 21.7 | 32.5 | 5.9 | 10.7 | 4.2 | 0.5 | 6.3 |

Mean and standard deviation of study variables are listed in Table 2.

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation, respectively, for subjects with authoritative parenting variables 25.97 and 6.84, authoritarian parenting style 17.93 and 7.35, permissive parenting style 18.4 and 6.60, novelty seeking 9.93 and 5.54, behavioral problems 23.25 and 11.9, problem-oriented coping strategies 57.11 and 9.74, emotion-focused coping strategy 51.55 and 10.11, avoidance-oriented coping strategy 48.78 and 10.76, and with addiction potential 48.30 and 12.06.

| Variable | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Permissive parenting | 18.04 ± 6.60 |

| Authoritarian parenting | 17.93 ± 7.35 |

| Authoritative parenting | 25.97 ± 6.84 |

| Novelty seeking | 9.93 ± 5.54 |

| Problem-oriented coping strategy | 57.11 ± 9.74 |

| Emotion-oriented coping strategy | 51.55 ± 10.11 |

| Avoidance-oriented coping strategy | 48.78 ± 10.76 |

| Behavioral problems | 23.25 ± 11.09 |

| Addiction potential | 48.30 ± 12.06 |

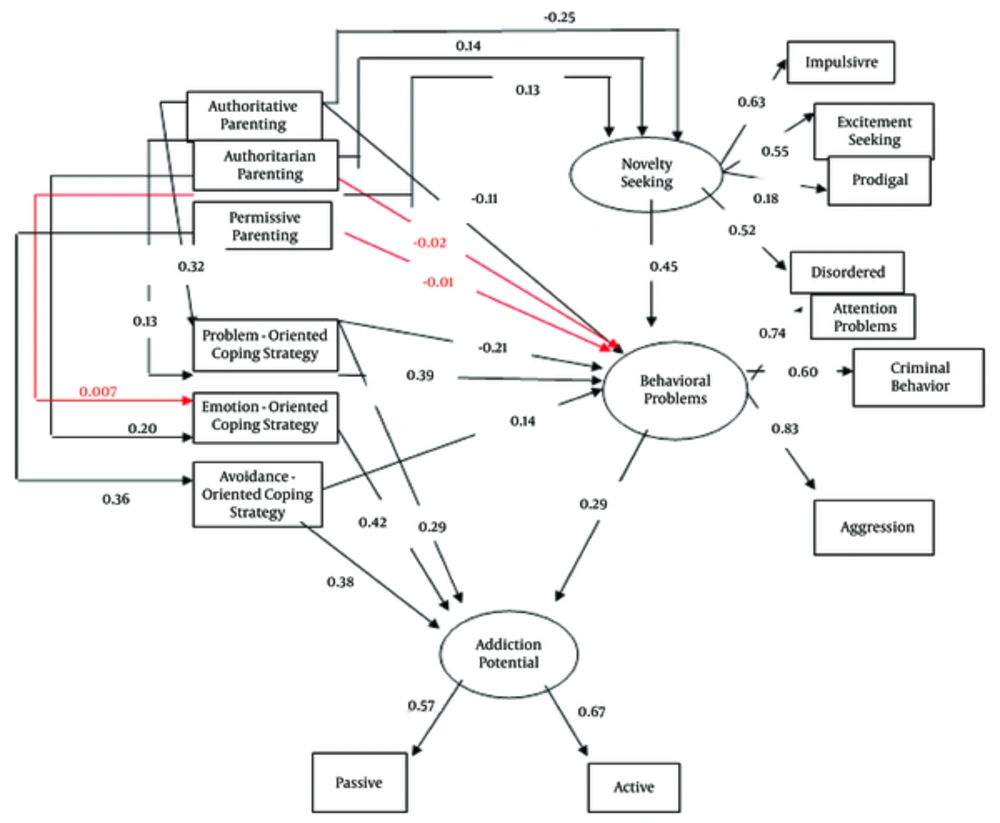

It is worth noting that the values of correlation coefficients between most of the variables in the level of 0.01 were significant. However, the relationships between authoritarian and permissive parenting style, permissive parenting style and novelty seeking, permissive parenting style and emotion-focused coping strategy, permissive parenting style and behavioral problems, authoritarian parenting style and problem-oriented coping strategies, authoritative parenting style and emotion-focused coping strategy, and problem-oriented coping strategies and emotion-focused coping strategy were not significant. The fitness indices are listed in Table 2. As can be seen, the value of indices of GFI, AGFI, NFI, CFI, IFI, and TLI is less than quorum 0.9 and relative Chi-square value is greater than quorum 3. The RMSEA value is also very high, at 0.1. These values indicate that the fitness of model is poor and needs to be modified. In order to enhance the fitness of model, three modifications were done, such that permissive parenting and avoidance-oriented coping variables errors, the variables errors of problem-oriented coping and avoidance-oriented and delinquency problems and active addiction potential were correlated with one another. In addition, the paths of authoritarian parenting style toward behavioral problems, permissive parenting style to behavioral problems, and permissive parenting style to emotion-focused coping strategy that were found to be not significant (see Figure 1) were removed from the model. After the changes, the revised model was tested. Also, fitness indices of the revised model are listed in Table 2.

Table 3 shows that indexes of fitness, including χ2 = 288.28, RMSEA = 0.07, χ2 / df = 4024, GFI = 0.93, AGFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.87, TLI = 0.84, IFI = 0.91, indicate a good fit of the modified model to the data. Thus the modified or final fitness model is acceptable. The last column of Table 3 shows the difference between the Chi-square of the proposed and the modified model (613.16 - 288.56); the difference between the degrees of freedom of the two models (74 - 68) shows a significant improvement, with Chi-square of 6.324 and the degrees of freedom of 6. As a result, the modified model is confirmed to be an improvement on the proposed model.

| Modified Model | Proposed Model | Indices |

|---|---|---|

| 288.56 | 613.16 | χ2 |

| 71 | 74 | df |

| 4.24 | 8.29 | χ2 / df |

| 0.93 | 0.87 | GFI |

| 0.90 | 0.79 | AGFI |

| 0.07 | 0.10 | RMSEA |

| 0.87 | 0.74 | NFI |

| 0.90 | 0.76 | CFI |

| 0.91 | 0.76 | IFI |

| 0.84 | 0.65 | TLI |

| 324.6 | Δχ2 |

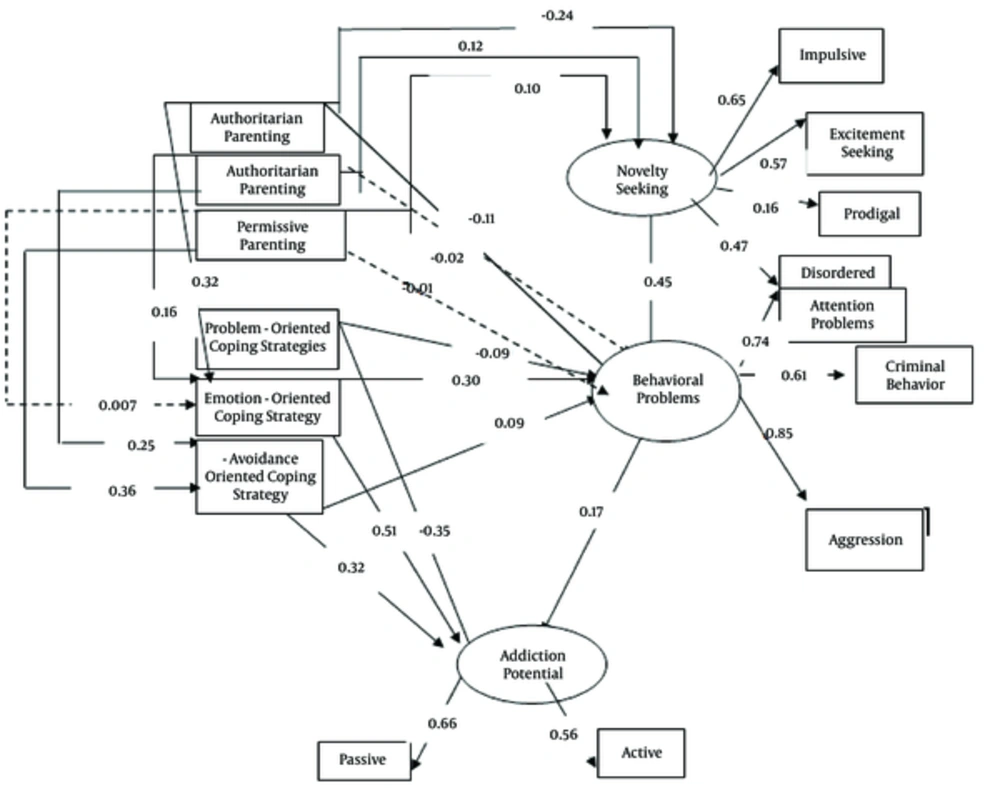

Coefficients of the modified model path related to the effect of risky and protective variables on addiction potential are illustrated in Figure 2.

As seen in Figure 2, based on standardized coefficients, all direct paths except three paths authoritarian parenting style to behavioral problems, permissive parenting style to behavioral problems, and permissive parenting style to emotion-oriented coping (continuous lines) are significant. Findings were obtained for the effect of emotion-oriented coping on drug-using potential is (P = 0.001, β = 0.51), the effect of novelty seeking on behavior problems (P = 0.001, β = 0.49), permissive parenting effect on avoidance-oriented coping (P = 0.001, β = 0.36), problem-oriented coping effect on addiction potential (P = 0.001, β = 0.35), authoritative parenting style effect on problem-oriented coping (P = 0.004, β = 0.32), avoidance-oriented coping effect on addiction potential (P = 0.001, β = 0.32), emotion-oriented coping effect on behavioral problems (P = 0.001, β = 0.30), authoritarian parenting style effect on avoidance-oriented coping (P = 0.003, β = 0.25), authoritative parenting style effect on novelty seeking (P = 0.001, β = 0.24), behavioral problems effect on addiction potential (P = 0.007, β = 0.17), authoritarian parenting style effect on emotion-oriented coping (P = 0.001, β = 0.16), authoritarian parenting style effect on novelty seeking (P = 0.01, β = 0.12), authoritative parenting style effect on behavioral problems (P = 0.01, β = 0.11), permissive parenting style effect on novelty seeking (P = 0.05, β = 0.10), problem-oriented coping effect on behavioral problems (P = 0.05, β = 0.09), avoidance-oriented coping effect on behavioral problems (P = 0.05, β = 0.09).

According to the results shown in Table 4, all indirect paths with two variables of mediator, with the exception of two paths (effect of permissive parenting on addiction potential through novelty seeking and behavioral problems, and effect of permissive parenting on addiction potential through emotion-oriented coping strategy and behavioral problems), are significant. It is worth noting that if a high level and low level of indirect effect are both positive and both negative, this means that its scope is zero and the path (direction) is significant.

| Paths | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | Percentile Bootstrap | ||

| Low | Up | ||

| From authoritative parenting to addiction potential through novelty seeking and behavioral problems | -0.17 | -0.23 | -0.10 |

| From authoritarian parenting to addiction potential through novelty seeking and behavioral problems | 0.12 | 0.066 | 0.185 |

| From permissive parenting to addiction potential through novelty seeking and behavioral problems | -0.003 | -0.069 | 0.059 |

| From authoritative parenting to addiction potential through problem-oriented coping and behavioral problems | -0.15 | -0.223 | -0.087 |

| From authoritarian parenting to addiction potential through on emotion-oriented coping and behavioral problems | 0.11 | 0.058 | 0.165 |

| From authoritarian parenting to addiction potential through avoidance-oriented coping and behavioral problems | 0.14 | 0.086 | 0.206 |

| From permissive parenting to addiction potential through emotion-oriented coping and behavioral problems | 0.018 | -0.041 | 0.079 |

| From permissive parenting to addiction potential through avoidance-oriented coping and behavioral problems | 0.09 | 0.017 | 0.09 |

aβ, indirect effect rate; low, lower level; up, Top level.

5. Discussion

This study has investigated the relationship between parenting style and addiction potential with the mediation of novelty-seeking variables, coping strategies, and behavioral problems. Overall, the findings show that authoritative parenting styles through problem-oriented coping strategies and behavioral problems, as well as novelty-seeking and behavioral problems, may be considered as protective factors against addiction potential. Authoritarian parenting styles through novelty seeking and behavioral problems, as well as through emotion-oriented coping strategies, avoidance-oriented coping strategies, and behavioral problems, are considered as risk factors for addiction potential. But a permissive parenting style only through an avoidance-oriented coping strategy and behavioral problems is a risk factor for addiction potential.

Our findings show that parenting styles have an effect on novelty seeking. The present study agrees with numerous others (11-14). In one study, hostile mothering was found to have an effect on temperament and novelty seeking among adolescents (33). Cloninger emphasized the role of environmental factors, especially parenting style, in the transformation and deformation of children’s nature into character traits (13). Similarly, our findings are consistent with the theory that sensation seeking and juvenile delinquency are associated with adolescents who have poor relationships with their parents and hence are prone to look for excitement and to have greater disinhibition traits than adolescents who have good relationships with their parents (34) Parents with an authoritative parenting style exercise strong control, discouraging autonomy in the child (35).

It seems that high novelty seeking and the inability to control impulsivity and adapt to the demands of their environment, especially parents and peers, makes young people prone to risky behavior and externalization problems (10). This finding is consistent with the interactive model of bio-social factors, which suggests that behavioral problems can be created from the direct influence of interactions between two biological risk factors, namely natural and environmental factors (36).

Further, the findings indicate that those with behavioral problems are more prone to drug use. Among the possible reasons are relationships with deviant peers and friends and the experience of many negative events, and the failure of an adaptive response to stress that leads to a decrease of negative affection and an increase of positive affection (37). Other studies have similar findings (14-16). Also, early levels of poor behavioral control foreshadow later drug use, according to models put forward by Cloninger (1988), Tarter et al. (2003), and Moffitt (1993) (38).

Parenting styles and their effect on coping strategies are one of the most important individual factors in promoting a tendency toward drug use. This finding chimes with social learning theory describing the lack of a suitable model of positive behaviors or positive emotion regulation skills, in high-conflict family environments with parent who have poor parenting styles (21), as discussed in several studies (22, 23). In fact, adolescents with parents who provide social support are more able to cope with stressful events and use active coping (problem-solving) more frequently than adolescents and young adults with authoritarian parents, because the former learn how to successfully develop active ways of coping (23). However, the findings of the present study show that a permissive parenting style does not affect an emotion-oriented coping strategy. Possible reasons for this inconsistency will be discussed at the end. The present findings regarding the direct effect of problem-oriented, emotion-oriented, and avoidance-oriented coping strategies on behavioral problems are consistent with the findings of several research studies (24, 25). Given that adolescence is a period of change and transition and is notoriously stressful, all the resources of a person are used, and adapting efficiently to this stage is a developmental predictor of subsequent suitable outcomes, such as higher levels of self-growth, higher self-esteem, lower levels of depression, and fewer behavioral problems (39). Efficient coping, such as problem-oriented coping, serves as a buffer against stress (40).

The present study showed that emotion-oriented, avoidance-oriented, and problem-oriented coping strategies affected addiction potential, as revealed also in other research (26-28, 41). Failure to effectively confront stress causes a person to feel inadequate, which in turn leads to feelings of anxiety, helplessness, and avoidance, and, according to Goleman, these different patterns of emotion such as anxiety, anger, irritability, depression, and so on can be a factor precipitating the onset of drug use (36). In contrast, an efficient coping strategy decreases the effects of stress and is considered a buffer against psychological pressure (42).

Our findings regarding the effect of authoritative parenting style on behavioral problems are consistent with those of other studies (19, 20). Parents with a strong parenting style, by having constructive communication skills, exerting positive reinforcement, and enabling monitoring and conflict resolution, provide structural reinforcement that deflects adolescents from developing behavioral problems (43). However, the present study indicates, on the contrary, that authoritarian and permissive parenting styles have no effect on behavioral problems, a finding that is inconsistent with other research (17, 18). Pursuant to these findings, in theory, in addition to the negative features of a permissive parenting style, its positive features include self-confidence and lack of inner inhibition. So, perhaps in the current study the scales are heavily tilted in favor of the positive aspects of this style (44). Authoritarian parental characteristics associated with adolescents do not always cause externalization behavioral problems, but other factors in this parenting style do have an effect on behavioral problems, including personality traits such as novelty seeking.

Of five rejected supposed relationships, four relationships are related to the permissive parenting style. Therefore, it is possible to reject the hypothesis for the following reasons. A) One is the nature of permissive parenting constructs: some researchers point out that this method is not a unified style. For example, Maccoby and Martin (1983) divided permissive parenting into two categories: spoiling parenting and rejecting and indifferent parenting (45). Perhaps this lack of consistency may explain the inconsistent findings. B) Some of the questionnaire items that measure this style are not complete reflections of it. A theory relating to the difference between control and responsiveness on the part of parents has proposed three parenting styles (46). If we consider control in a spectrum ranging from strict control at one end to poor control at the other, it is expected that the items designed to evaluate the permissive style assess poor control, but the subscale items relating to permissive parenting actually assess proper control, rather than poor control. C) Perhaps in the discourse of adolescents participating in the study, permissive parenting means that the parents reject the authoritarian practices and traditional excessive restrictions of Iranian society. To understand the truth or inaccuracy of these explanations, independent studies are needed. At the end, it should be acknowledged that a causal model fits the data properly. However, the fact that the data fits does not necessarily imply that the model is correct. There may be other models that fit the data equally well. Also, data was gathered with questionnaires, which involved self-assessment, so the students answered them according to their unique contexts and there may be bias in their responses. A further limitation is that the students were in third grade in high school, and it is impossible to generalize the results to other students in other grades. Finally, it is recommended that, in addition to repeating the present study with children of different age groups, especially younger age groups because the age of initiating substance use is falling the effects of other variables such as gender, parents’ personality, influence of peers, and economic status of the family should be investigated in future models.