1. Background

Methamphetamine is the most common illicit amphetamine-type stimulant (ATS) used globally (1). Based on the estimates, methamphetamine use disorder caused more than 800,000 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) in 2016 (2). The adverse events of methamphetamine use are attributable not only to direct biological effects but also to psychological effects such as violent behavior or suicide (3), more susceptibility to injury (4), committing a crime, and recidivism (5, 6). These adverse events cause a higher mortality rate among those with problematic use of or dependence on methamphetamine than the general population (7).

In Iran, ATS use was rare before 2005 (8). According to the latest national household survey on the prevalence psychiatric disorders in the general adult population in 2011, nearly 0.5% have used ATS, and 0.4% met the criteria for ATS use disorder (9). However, the only available information about an increase in methamphetamine use has been reported in patients of methadone maintenance therapy (10).

Despite the increasing prevalence of ATS use, little is known about the course of methamphetamine use, use disorder, and the incidence of adverse events in Iran. Regarding people who use methamphetamine (PWUM), previous follow-up studies have primarily been conducted on treatment-seeking patients in developed countries (11-13).

2. Objectives

The Iranian Mental Health Survey (IranMHS) (14) provided reliable data at the national level on substance use and use disorder. After six years, we followed the identified cases and aimed to investigate their current pattern of substance use, the incidence of adverse events, and service utilization. The result of this project on opioid and cannabis use has been described elsewhere (15, 16), and here, we discussed the findings on those who use methamphetamine.

3. Materials and Methods

This study is a descriptive 6-year follow-up evaluation of a case series of PWUM. A total of 7886 adults aged 15 - 64 years (response rate = 85.7%) were recruited with a probabilistic sampling of Iranian households in IranMHS in 2011. The assessment of substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders was performed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) version 2.1 (9, 14).

Participants who used methamphetamine more than five times in the past year, positively responded to the screening question of the CIDI interview, and provided permission for future contacts to be considered eligible. Eligible participants were contacted via telephone. The failed telephone contacts were followed by sending an invitation letter.

To verify the vital status of the participants, family members were inquired about the incident, the date, and the reason for death. Two registries from the National Organization for Civil Registration and the Ministry of Health’s death registry were also searched. We used several identification indicators to ensure participants’ identity.

For the follow-up study, a 48-item questionnaire was designed to evaluate current sociodemographic status, substance use in the last 12 months, and major adverse events since the index interview. The adverse events included suicide attempts, incarceration, homelessness, traffic accidents, violent behavior, non-fatal overdose, and unemployment (for baseline employed participants). Violent behavior, traffic accidents, and non-fatal overdose were considered serious if they resulted in admission to the emergency department or led to judicial involvement.

More details about IranMHS have been described elsewhere (9, 14). The current study was led by core investigators of IranMHS who had access to the participants’ identity information. The protocol of this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1396.3303).

4. Results

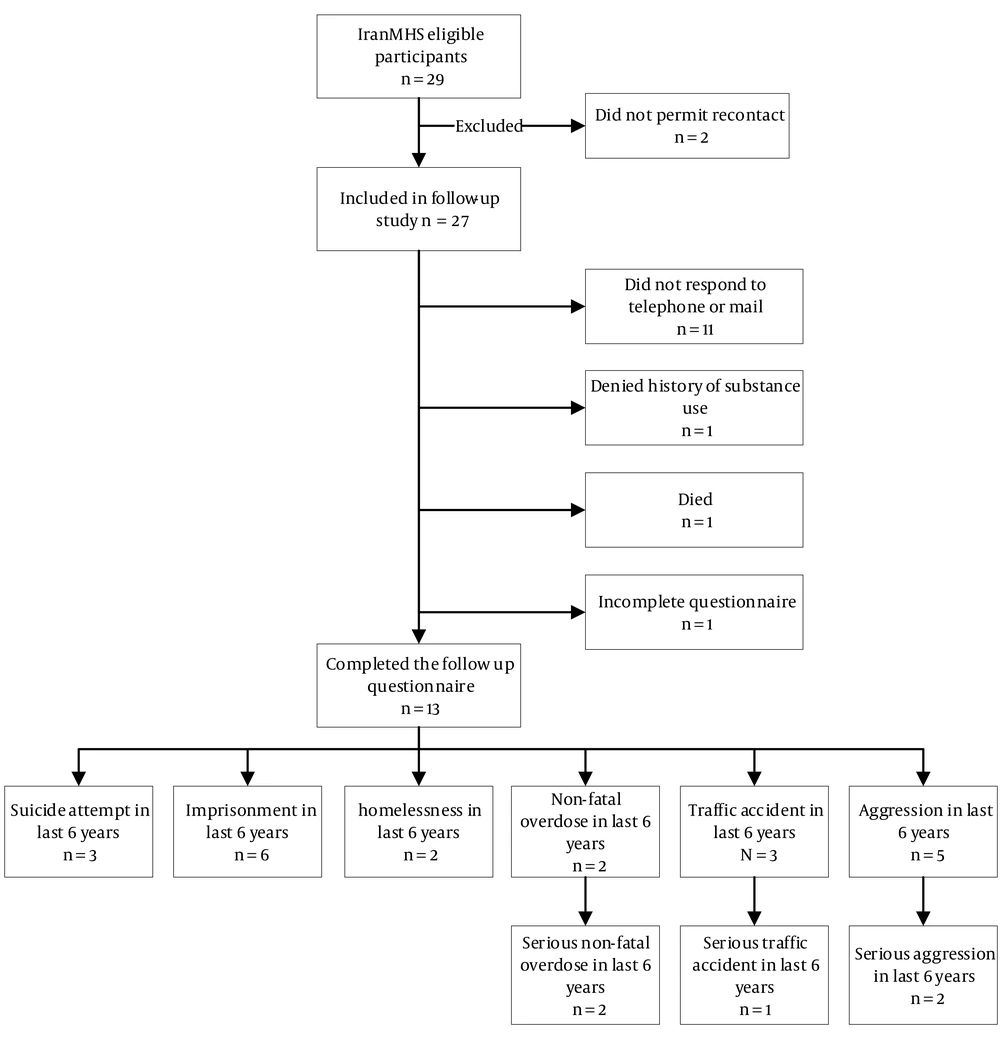

Among 29 eligible participants, 2 did not permit future contact. Of the 27 remaining participants, 14 were successfully contacted by the research team, but 1 was excluded due to an incomplete interview (Figure 1). Among 13 non-respondents, 1 was deceased, 11 did not respond to telephone contact or mail, and 1 denied a history of methamphetamine use. The average follow-up time was 6.58 years (SD = 0.30).

Table 1 summarizes the findings of 14 cases. All subjects were male. The age range was 19 - 44 at baseline (mean = 28.6, SD = 8.3). Eight had comorbid psychiatric disorders. The diagnosis was a mood disorder in 6, anxiety disorder in 2, and primary psychotic disorder in 1 participant. Ten fulfilled the criteria for methamphetamine use disorder at baseline. Nine were diagnosed with multiple use disorders. The most common frequency of methamphetamine use was 3 - 4 days per week (N = 7) and daily/almost daily (N = 3) at baseline.

| Respondents | Age (y) | Education | Province | Rural/Urban | Marital Status | SES | Employment Status | Use Disorder a | Service Used b | Psychiatric Comorbidities a | Frequency of Methamphetamine Use a | Major Outcomes in the Past 6 Years b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | I | I | I | I | F | I | I | F | I | F | I | I | F | F | |

| 1 | 19 | High school | Fars | Urban | Single | Single | Middle | Student | Unemployed | Methamphetamine, opioid, cannabis, hallucinogen, inhalants | MMT (without supervision), detoxification, camp, refer to pharmacy c, NA | Primary psychotic disorder | 3 - 4 days per week | Abstinence d | Suicide attempt, severe overdose e, violent behavior |

| 2 | 21 | High school | Kurdistan | Rural | Single | Single | Low | Student | Unemployed | Opioid | None | Mood disorder | Almost daily | Abstinence | Incarceration |

| 3 | 21 | Middle school | Isfahan | Urban | Single | Single | Middle | Employed | Employed | Opioid, alcohol | Camp, NA | Mood disorder | 3 - 4 days per week | Abstinence | None |

| 4 | 22 | High school | Isfahan | Urban | Single | Married | Middle | Unemployed | Employed | Methamphetamine, opioid, cannabis, cocaine, other | MMT, Camp, refer to a pharmacy, NA | None | Almost daily | Abstinence | Traffic accident |

| 5 | 22 | High school | Tehran | Urban | Single | Married | High | Employed | Employed | Methamphetamine, cannabis | None | None | 1 - 3 days per month | Abstinence | Suicide attempt, severe overdose |

| 6 | 23 | Middle school | Qazvin | Urban | Single | Married | Middle | Unemployed | Employed | Methamphetamine, opioid, cannabis | MMT, Camp, NA | Anxiety disorder | 1 - 2 days per week | Abstinence | Incarceration, severe violent behavior |

| 7 | 24 | High school | Yazd | Urban | Single | Married | High | Employed | Employed | Methamphetamine | None | Mood disorder | 3 - 4 days per week | 1 - 3 days per month | Incarceration, homelessness |

| 8 | 25 | University | Markazi | Urban | Married | Divorced | Middle | Employed | Employed | Methamphetamine, opioid, cannabis, cocaine, other | MMT | Mood disorder | 3 - 4 days per week | 1 - 3 days per month | Traffic accident, incarceration, violent behavior, homelessness |

| 9 | 32 | High school | Qazvin | Rural | Separated | Married | Low | Employed | Employed | Methamphetamine, opioid | NA | Mood disorder | 3 - 4 days per week | Almost every day | Incarceration, violent behavior |

| 10 | 35 | Elementary | Golestan | Rural | Married | Married | Low | Unemployed | Unemployed | Methamphetamine, cannabis, opioid | None | Anxiety disorder | 1 - 2 days per week | Abstinence c | None |

| 11 | 35 | University | Tehran | Urban | Single | Single | High | Unemployed | Employed | Methamphetamine | None | None | 3 - 4 days per week | Abstinence | None |

| 12 | 38 | Elementary | Hamedan | Rural | Married | Married | Middle | Employed | Unemployed | Opioid | MMT, NA | None | Less than once a month | Abstinence | Traffic accident, incarceration, suicide attempt, severe violent behavior f |

| 13 | 39 | Elementary | East Azarbayjan | Rural | Married | Married | Middle | Employed | Unemployed | Methamphetamine, opioid, alcohol | Camp, NA | None | 3 - 4 days per week | Abstinence | None |

| Death | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 44 g | High school | Tehran | Urban | Separated | - | Middle | Unemployed | - | None | - | Mood disorder | Almost daily | - | Death |

Abbreviations: I, Iran Mental Health Survey; F, follow-up 2017-2018; SES, socioeconomic status; NA, narcotics anonymous; MMT, methadone maintenance treatment.

a The highest frequency used in the past year.

b In the past 6 years.

c Without the physician’s prescription

d Abstinence for at least 1 year

e Referred for treatment

f Injured victim was referred for treatment or judiciary involvement of the perpetrator.

g Age at death

At the 6-year follow-up and from a total of 29 individuals, we recorded 1 death (Figure 1). The death occurred two months after the baseline survey, with an unknown cause. Ten of 13 interviewed individuals reported being abstinent, and 2 reduced their frequency of methamphetamine use. Six individuals experienced incarceration, 5 had episodes of violent behavior (2 serious violence), 3 attempted suicides, 3 had traffic accidents (1 serious injury), 2 had a serious non-fatal overdose, 2 experienced homelessness, and 2 became unemployed.

Of the 10 individuals with methamphetamine use disorder at baseline, 6 received treatment for substance use disorder at least once during the 6-year follow-up, all of whom were diagnosed with opioid use disorder as well. None received specific health care treatment for stimulant use disorder. The most common service was participation in Narcotics Anonymous self-help groups (N = 5), followed by receiving methadone maintenance treatment (N = 4) and admission to mid-term residential treatment centers (camps; N = 4).

5. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to follow PWUM from the general population in Iran. Several studies have investigated the associated consequences of methamphetamine and other amphetamines in different countries. A recent systematic review concluded that use of amphetamines is associated with higher odds of psychosis, depression, violence, and suicidality (3). Consistently, data from an Australian cohort study showed that people who use drugs had an odds ratio (OR) of 8.2 to commit a violent crime in months in which they use methamphetamine (5). Another systematic review that included data from 23 cohort studies found that people with different amphetamines use disorders (including methamphetamine) are experiencing significantly higher all-cause mortality rates with a pooled crude mortality rate of 1.1 per 100 person-years (7). Similarly, the result of a meta-analysis of 8 studies showed that the use of amphetamines would result in a 5.6-fold increase in the chance of having a fatal road accident (17).

We recorded one death among 29 eligible individuals. Other studies have reported higher mortality rates in PWUM compared to the general population; a higher odds of mortality (6.8 folds) for PWUM was estimated in a systematic review (7). Follow-up studies in a large case dimension are needed to determine the odds of mortality among PWUM in Iran.

In our study, more than two-thirds of participants experienced at least 1 adverse event, of which more than half reported facing 2 or more adverse events. Violence and incarceration were the most common adverse events in our sample. A systematic review reported that violent behavior could be up to 2.2 times higher in PWUM and 6.2 times higher in those with methamphetamine use disorder compared to the general population (3). Other studies have concluded that violent and non-violent crimes and recidivism are more prevalent in PWUM compared to the general population (5, 6).

Suicide attempts, overdoses, and traffic accidents reported in our sample. According to available evidence, these events contribute to higher rates of injuries seen in PWUM (4). A systematic review estimated that any use of methamphetamine was associated with a 3.6-fold increase in the risk of committing suicide (3). Another study reported an increased odds of 6.2 for traffic accidents that resulted in injury in PWUM (17). These findings suggest that incorporating injury-prevention programs in substance use treatment packages is necessary.

With only 1 exception, all our participants reported abstinence or decreased frequency of methamphetamine use. Although other published studies have observed the same decreasing pattern, the reported abstinence rates in these studies are lower than our sample. A systematic review published in 2010 reported an estimated annual remission rate of approximately 17% for those with methamphetamine use disorder (13). A more recent 5-year follow-up study that recruited PWUM with and without use disorder from the general population reported a 20% 1-year abstinence (12). We did not confirm the reported abstinence with urine tests; this may have caused an under-reporting of continuing drug use in our study.

Among individuals with methamphetamine use disorder, slightly over half received at least one substance use treatment service. All subjects who received treatment services had comorbid opioid use disorder. No one received specific health care services for methamphetamine use. This pattern is the same as the baseline study (9). Although the overall proportion of subjects receiving any substance use treatment is comparable with developed countries (18), not utilizing specific services for methamphetamine use disorder is noteworthy. Several packages of cognitive-behavioral treatment for stimulant use disorder have been introduced in the country, and planned to expand their integration into the services provided by outpatient drug treatment centers; however, the coverage is still low.

Psychiatric comorbidity was frequent in our sample. More than half of the participants were diagnosed with a mood disorder, which is a high rate compared to the general population (19). Similarly, a recently published systematic review reported that any use of methamphetamine is associated with an OR of 1.6 for depression (3). However, these results are only temporal associations, and causality should be addressed with further prospective research.

This study has some limitations, including a descriptive design, small sample size, and inevitable drop-out rate, which make it difficult to draw general conclusions. Moreover, the female subgroup of PWUM was absent in our sample. Also, the high concurrence of other substance use disorders makes it difficult to determine to what extent the observed events are associated solely with methamphetamine use.

In summary, we presented the 6-year follow-up outcomes of PWUM recruited from the general population. Our sample experienced a high rate of adverse events. No individual with methamphetamine use disorder received specific health care treatment. Future prospective studies on a representative sample of people who use only methamphetamine are needed to determine the causality and the effect size of methamphetamine use on the occurrence of adverse events.