1. Background

According to the treatment episode data set (TEDS), about 32.4% (588,764) of admissions to substance abuse treatment facilities were women, up from 30% in 2002 (1). The majority of these women is of childbearing age, have children, and are the primary childcare provider (1-5).

Women with substance abuse disorder differ from men in their patterns of substance abuse, treatment-related behaviors, and risks for relapse (6). Studies have shown that women can develop medical and social consequences of addiction faster than their male counterparts and can be more susceptible to relapse (6-8). In addition, women with substance use disorders are more likely than their male counterparts to have coexisting psychiatric problems, low self-esteem, and extensive histories of traumatic life events (3, 9, 10), and to experience mood, anxiety, and eating disorders, as well as post-traumatic stress disorder (8).

1.1. Motivators for Recovery

Among women, personal characteristics such as desire for work and educational training, desire for stable relationships as they develop, prior successful experiences in other life areas, and confidence in the treatment process and outcome can motivate treatment retention. In addition, other factors related with the treatment characteristics can motivate women to remain in treatment: supportive therapy, a collaborative therapeutic alliance, and on-site child care and children’s services (6, 11).

For mothers, the concern for the well-being of the fetus/child and the desire to provide care for the children and maintain or recover child custody serves as a major motivation to seek treatment and maintain abstinence from substances (11-14). Moreover, raising children has been associated with improved engagement in drug abuse-related interventions (3, 8, 15). The incorporation of family members in the recovery process contributes to preventing relapse and extending time to relapse (16), providing greater potential for involvement in supportive family relationships that foster sobriety and adherence to treatment (17, 18).

1.2. Challenges for Recovery

Women with substance abuse problems experience a unique set of challenges when attempting to remain substance-free, including low self-worth, interpersonal conflicts that interfere with treatment, an inability to sever ties with the drug-using network and environment, and a lack of knowledge about relapse prevention coping skills (6, 11, 19, 20). In addition, compared to men in recovery, women tend to have a greater involvement with family, and thus have the potential for more problematic relationships with family members and substance using partners that challenge sobriety (6, 21). Family functioning indicators that can predict substance abuse relapse among women include emotional distance, lack of open communication, and lack of support from male partners (22, 23). Additionally, a factor that can challenge women’s recovery and increase the risk of relapse is that women tend to be more stigmatized and stereotyped. This may result in barriers to accessing services which can prevent or impede recovery (24).

1.3. Attitudes and Preferences for Family Involvement in Recovery

Substance abusing women prefer holistic services that allow dependent children to attend treatment with parents (11). However, little is known about the perspective of mothers in drug treatment regarding the impact and involvement of family in substance abuse recovery program interventions (25).

2. Objectives

Given the impact of drug abuse on women and their families, it is particularly important to get women’s perspectives on access to family-based interventions specifically tailored to their needs that can help them to prevent relapse and improve their health. The aim of this paper is to gain the perspectives of mothers in substance abuse treatment (or recently in treatment) regarding the following factors: (a) motivators for recovery, (b) challenges to recovery, and (c) attitudes and preferences for family involvement in recovery. This knowledge is intended to inform the development of family-based substance abuse treatment approaches for mothers in substance abuse recovery for preventing relapse and improving their health.

3. Patients and Methods

This qualitative descriptive study explored the perspectives of mothers currently or recently (up to 3 years prior) enroll in substance abuse treatment. The qualitative descriptive method was selected because it provides an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of interest by obtaining a detailed view about the meaning that participants give to their experiences (26).

3.1. Data Collection

Qualitative semi-structured in-depth interviews were selected as the primary data collection method for this study. A quantitative demographic questionnaire was used to collect participants’ socio-demographic information including age, education, and years in the U.S. The survey also collected basic information about the woman's substance treatment (in-patient or outpatient, number of treatments, and the length of the treatment) and family information (household members and caregiven arragements for children). The entire procedure, including consent, the quantitative demographic questionnaire, and the qualitative interview, took between 45 and 75 minutes. Interviews were conducted in participant’s preferred language (English or Spanish) using a conversational style. Five interviews were conducted in Spanish, and eight interviews were conducted in English. All interviews were conducted by a bilingual interviewer (English-Spanish).

3.2. Participants

Thirteen women participated in the study (n = 13). Saturation was used to determine the sample size for the qualitative component of the study, indicating that the limits of the phenomena had been covered. When saturation was reached, the in-depth interviews were discontinued (27). This study achieved saturation of data with 13 women. Eligible participants met the following inclusion criteria: (a) being a mother, (b) age 18 or older, (c) currently or recently in substance abuse treatment (up to 3 years prior), and (d) English or Spanish speaking. All of the study’s participants were treated at two community-based substance abuse treatment centers in an urban area of south Florida. These centers provide residential and outpatient substance abuse services for men and women.

The participant ages ranged from 23 to 51 years old. Most of the participants (n = 8) lived with or were planning to live with their children when they finish their treatment; three participants had grown children, and 2 participants no longer had custody of their children (Table 1).

| Sample Characteristics (n = 13) | Valuesa |

|---|---|

| Interview language | |

| English | 8 (61.5) |

| Spanish | 5 (38.5) |

| Age | 10.7 |

| Education | |

| Less than elementary school | 1 (7.7) |

| Elementary school | 5 (38.5) |

| High school | 5 (38.5) |

| College/university degree | 2 (15.3) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White Hispanic | 5 (38.5) |

| African American/Black | 3 (23.1) |

| Native American | 1 (7.7) |

| White non-Hispanic | 4 (30.7) |

| Currently in treatment (of some sort) | 10 (76.9) |

| Length of current treatment, months | 5.7 (4.3) |

| Prior treatment (before current treatment) | 8 (61.5) |

| Only formerly in treatment | 3 (23.1) |

| Current outpatient treatment | 2 (15.4) |

| Current inpatient treatment | 11 (84.6) |

| Type of treatment | |

| Illicit drug treatment | 8 (61.5) |

| Alcohol abuse treatment | 2 (15.4) |

| Prescription drug abuse treatment | 1 (7.7) |

| Alcohol and illicit drug abuse treatment | 2 (15.4) |

| Number of children | 1.38 (0.9) |

| Children 18 or younger | 9 (69.2) |

| Children over 18 | 4 (30.8) |

aValues are expressed as No. (%) except for age, length of current treatment, and number of children which are expressed as mean (SD).

3.3. Procedures

3.3.1. Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Miami. Data were stored in a locked area for research files and digital files were saved in password protected computers.

3.3.2. Recruitment

Recruitment was facilitated by the substance abuse treatment personnel (nurse manager, case manager, or psychologist) at the clinic sites. Clinical personnel contacted women who they knew had children and who were currently in or had recently attended substance abuse treatment. The clinical personnel asked the women if they would be willing to meet with a researcher about the study. The clinical personnel set up an appointment for a member of the research team to meet the study candidate. After the study team member explained the study to the participants and answered their questions, the participants who agreed to participate were asked to sign an informed consent form, and the interview was conducted immediately upon consent.

3.3.3. Recordings and Transcription

Interviews were audio recorded with participant permission. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim in Spanish or English by a transcription service that transcribed the information in the original language. The research team verified the transcriptions and discrepancies were corrected.

In-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide (Box 1). Probing questions were asked to elicit more information if participants gave limited or vague responses. All study procedures took place in a private room at the treatment center.

| Interview Guide |

|---|

| What motivated you to receive treatment and what motivates you to stay substance-free? Who were the people who motivated you and who inspired you? Who is/are the main people in your life that it’s important to you to be there for? Who are the people who are there for you? |

| What do you think are the factors in your life make it most challenging for you to stay substance-free? What are the things in your life that are demanding or stressful? Every family has difficulties and disagreements; how do difficulties or disagreements in your family affect your ability to stay substance-free? |

| How do you feel about involving your family in your recovery? Who are the people who you most want to involve? Who do you feel it is most important to involve and why? Who would you not want to involve and why? Who in your life would be interested in being involved? Are there people other than family who would be important to involve? What would be the most difficult thing about involving your family? |

| If there were a program that involved your family how would you like it to be? What types of family issues would you feel would be most helpful to you to work on? Would you like it if a counselor came to your home? Would you like it if your family accompanied you to this center? What do you know about family therapy and what is your impression? |

3.3.4. Analysis

Qualitative content analysis (inductive) was used to identify and describe the major themes and sub-themes that emerged from the interviews. This is a dynamic type of analysis that is oriented toward recognizing, coding, and categorizing patterns from text data (28, 29). Directed content analysis, a type of analysis recommended when prior research related to the phenomenon of interest can benefit from further analysis (30), was used to analyze the transcripts. In this study, we had a priori concepts about possible themes based on the research literature and on clinical experience conducting family therapy with women in recovery (31).

The coders of the current study applied predetermined subthemes and themes based on previous research findings in this field to guide the analysis of the interviews. There was a team of three bilingual coders, and each transcription was coded line by line by two of the coders in the transcription original language (Spanish or English). Following transcription and coding, all three coders met to decide on the final themes/sub-themes from the list of predetermined sub-themes and from new findings developed during the coding process. The coders discussed and resolved differences in the analysis by considering the meanings until they reached full agreement. This comparison resulted in modifications of the original sub-themes to accommodate new data that emerged from the interviews with the purpose of ensuring the best fit of the data.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 18.0 was used for descriptive analysis (e.g. mean, standard deviation, percentage) of participants’ sociodemographic information.

4. Results

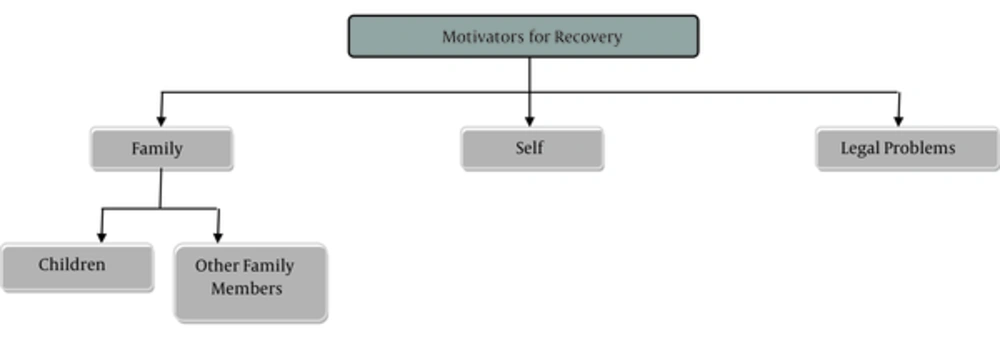

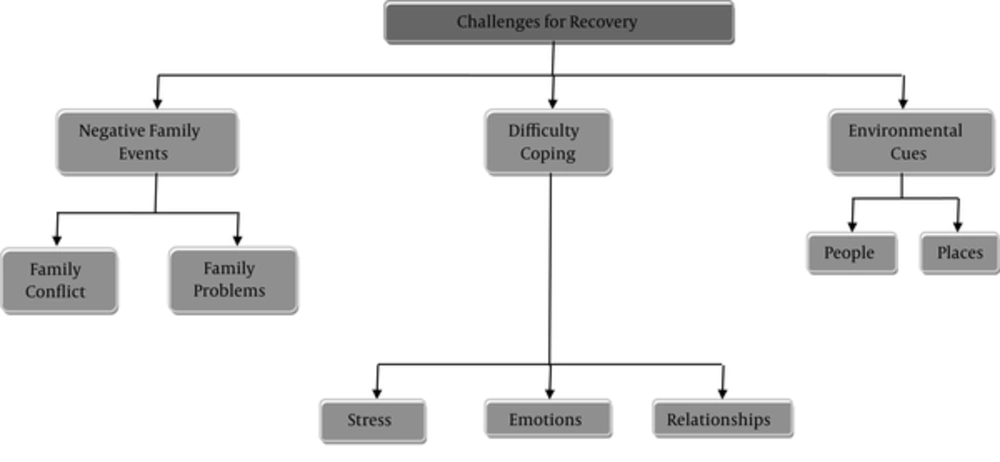

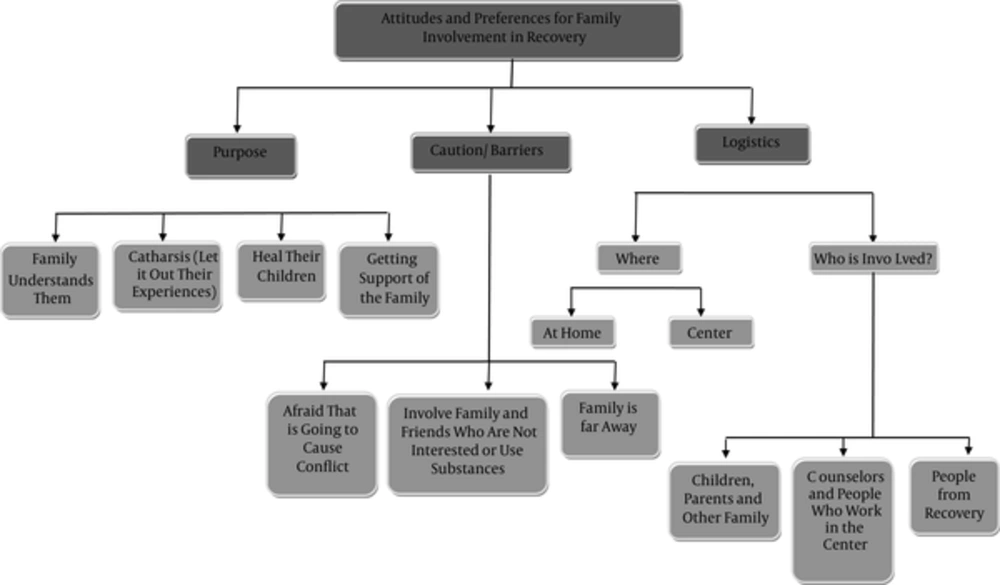

We found three major themes: (a) motivators for recovery, (b) challenges for recovery, and (c) attitudes and preferences for family involvement in recovery. Figure 1 - 3 show the sub-themes that emerged for each of the major themes. Quotations from participants about the themes are taken verbatim from the transcripts.

4.1. Motivators for Recovery

Three sub-themes emerged regarding motivators for seeking substance abuse treatment and remaining substance-free: family, self, and legal problems. Participants described how these motivators helped them to enter and sustain their recovery process.

4.1.1. Family

The first sub-theme was family. Women described their children, parents, and partners as important sources of motivation and support. Families provided participants motivation and energy to change and to be better persons. One woman said:

My children and husband agreed and they made me see that it [treatment] was necessary... I tried to do it alone and I could not do it…I had already dealt with some [programs] and I did for a while [remain substance-free] but then it did not work and then it was when my family helped me…

Children were sources of motivation for these women and provided a sense of purpose to remain substance-free. Feeling that they needed to be there for their children, women wanted to set a good example and support them. One woman made the following comment:

My son encourages me just because of the fact that I am his caregiver and I am his mother. So that was a big part of me coming here and I wanted it for my son. I want him to become a better person…

4.1.2. Self

The second sub-theme under motivation was self. Several women mentioned that receiving treatment could make them feel that they were better persons or healthier. Many women expressed that they did not want to perpetuate the suffering and the problems caused by their addiction, and they did not want to continue feeling emptiness and a lack of purpose and meaning in life. One woman said:

What makes me stay substance [free] is the pain that I have endured. Using drugs has taken me to a dark place … I didn’t have nothing to live for… and I had to come to realize, you know, I was a very sick person.

Participants often perceived treatment as an opportunity to rebuild their lives and feel healthier, thus providing them a sense of worth and achievement. One woman said:

I am almost sick and tired [of] being sick and tired or getting high, that’s what makes me substance free, I don’t want to get high anymore…

4.1.3. Legal Problems

The third sub-theme under motivation was legal problems resulting from their substance abuse associated with going to jail or losing the custody of their children. Some participants had previously experienced legal problems did not want to repeat them. One woman commented:

I wouldn’t wish jail for no one and if that doesn’t wake you up then I don’t know what will, so jail motivated me to do the right thing, do not get high.

4.2. Challenges for Recovery

Three sub-themes emerged under the theme of challenges for recovery: negative family events, difficulty coping, and environmental cues (“people and places”).

4.2.1. Negative Family Events

Participants described family conflicts (i.e., arguments with their relatives and anger with absent parents or abusive partners) and family problems (e.g., family violence, substance abuse problems of others, and sexual abuse) as barriers in the recovery process. When family conflicts were present, the relationships with other members generated emotional problems and stress, leading some women to return to using drugs and alcohol. One participant said:

Me and my mom used to be real close. And when I started using drugs, I slowly just shut down, and then we never agreed on anything, like I would never take advice from her… and so like if I got mad at her, yeah, that would trigger me, and it would trigger me in a sense to where I am either upset so I am going to go, use because I am upset…we used to get into wild arguments.

In other cases, participants described isolation and lack of family support as a hindrance to recovery. One woman shared the following thoughts:

We have always been together [with my son] and I thought that after a month [in treatment] that I was not in the house, he [my son] was coming here ... And I saw that it has been a month and he has not come to a single therapy, that made me feel bad, very bad…There are times that I have asked my mom to go to a group but she cannot go, because she works, because she is tired, or because ... If she had learned a little more of the need of a group in the recovery she would have supported me more…

4.2.2. Difficulty Coping

The second sub-theme that emerged regarding recovery challenges was difficulty coping with stress, emotions, and relationships (conflicts) with other people. If women were not able to cope, they felt overwhelmed and out of control, which triggered them to use substances. One woman explained:

I couldn’t cope with anything, bills, that [was] too much. I had my son when I was like 19 years old, and that was too much… I always kept doing things wrong over and over and over again… So it was kind of like a circle, so like I was stuck, like one of little troubles or something, like run in a little cage in a circle over and over again, I was stuck there.

4.2.3. Environmental Cues (“People and Places”)

The third sub-theme under challenges for recovery was environmental cues. Participants described that being around people or places where the use of substances was accepted or expected jeopardized their intentions to achieve sobriety and stay in treatment.

In my home I used to just get high in my room. So, I suggested to my daughter, “Listen, move everything out of that room. I don’t want to live in that room no more… It going to remind me of such darkness cause that’s all I used to do is get high.” So, that’s the place.

4.3. Attitudes and Preferences for Family Involvement in Recovery

All of the women described positive attitudes towards involving their families in their treatment and the recovery process. Sub-themes that emerged were the purpose of involving family, cautions/barriers regarding involving family, and logistical issues for involving family.

4.3.1. Purpose of Involving Family

Participants mentioned the following reasons to involve family in their treatment and recovery process: so that their family members understand them, catharsis (letting out their experiences), healing their children, and getting support from the family.

Women expressed that the opportunity to communicate during family sessions would allow the family to understand and know them better. One participant mentioned:

When I went to court my mom was there. I hugged my mom and I whispered in her ear, I said, “I would love for you to come to family therapy so you could get to know me because you don’t really know me.”

Participants mentioned that family therapy can provide a venue to express feelings and experiences to family members that they usually do not feel able to discuss. One participant mentioned explained:

It [family therapy] would help because there’s so much happening in families …You know, they say “whatever happens in the family stays in the family” but families need to be able to sit around, and talk, and communicate with each other, you know, and tell how you feel. I believe that’s how families need to do.

These women also see the incorporation of family as a healing experience for their children. Women felt that involving their children in the recovery process would positively impact their family relationships because the children can see their change and regain trust in them as mothers. One woman said:

Addiction is a disease, but I want her to know that it’s an ongoing thing, that recovery is an ongoing process …. She knows [about my addiction], she just don’t want me to turn my back on her and go out and use again. Like she told me, she wants her mother back, and it really hurts to hear your kid say that…

In relation to gaining support from their families, several times women described that they felt ashamed about their past behavior. They feel that family therapy was positive for their lives and could help them to show their families that they have changed and that family support is crucial in the recovery process. A woman said:

I just want them [family] to notice that I have done this to prove a point to them that I can change, that I can stay sober… I want her [my daughter] to know that it’s a disease… and I want her [my daughter] to be involved to know people can get help, and people can change, and I don’t want her to go down the wrong path you know, and use drugs.

4.3.2. Cautions/Barriers Regarding Involving Family

Despite unanimously positive attitudes towards family therapy, some of the women described some cautions/barriers associated with family therapy. Some women were afraid that this type of therapy would cause conflict because it would disclose secrets that they had with other family members [i.e. their addiction]. For example one explained:

I do not like to lie, but to avoid pain to my mother, do you understand? [because she] with so much wishful thought, sacrifice, so much love [raised me], it is not that I do not want to include her but I would be shameful because it would very hard for her to believe that her daughter, a good girl was a drug addict.

In other cases, women described some barriers in involving their family and friends in their recovery. Several women felt judged by some of their relatives and did not feel able to discuss their substance problems with them. In other cases, women did not want to involve people who use substances. A woman shared the following thought:

Yes, for example, my family here ... they do not accept [substance abuse problems]. In my country, you know, becoming alcoholics and drug addicts, is something very wrong, very, very, bad, very shameful…My family will not ever participate in a program, I mean, in fact they never have come here….

4.3.3. Logistical Issues for Involving Family

Women mentioned logistical aspects that were important for the family therapy. They were willing to receive family therapy in a place that was comfortable for them, which could be at either their homes or therapy centers. Some women felt that family therapy at home was convenient and they they would like to have this opportunity, so all the family can participate. One woman said:

Yeah. And if I can’t come, my family couldn’t come to them, [if] a counselor [come to us], then there would be no excuse. If they can come to us there is no excuse so that those that didn’t participate it would be for their own self-esteem and I mean of course I will have to try and get them involved but if they really choose not to get involved then I could really look at it as they are lost as we would be relying on two wonderful people or many others.

Women also talked about who they wanted to involve in the family therapy. They were willing to involve their children, parents, other family members, counselors and other people who work in the recovery centers, and people receiving treatment. Women expressed the view that a counselor or therapist could help them discuss things that were both important for them and their families and that they were unprepared to discuss or confront with their families without a mediator. One woman said:

Family therapy is definitely something I would strongly advice and advocate for, very strongly advocate because it’s definitely good to have a mediator in the middle of issues that both of us are ignorant to or either one of us are ignorant to. So family therapy A-plus

5. Discussion

The findings of this study indicated that one main motivation for recovery among mothers with substance abuse problems is their family, especially their children. The presence of the family provides a strong support system and allows for positive parent-child interactions, which reduce the risk of relapse (32). The influence of the family during the recovery process has been extensively described in the literature (6, 11). The social support of having a marital partner reduces women’s use of substances as a coping strategy (5), and it has been reported that mothers are motivated to enroll in treatment and remain without relapse when they are working toward regaining child custody and if they receive support to enhance their parenting skills (11).

Mothers with substance abuse disorders have been vilified in our society and are often deemed “unfit” to raise children by the lay public, social service providers, and health care providers (6, 33, 34). They have rarely been invited to share their views about motherhood and how it affects their recovery. While there is ample evidence of the deleterious effect on children when mothers have substance abuse disorders (35), this study illustrates that mothers who seek substance abuse treatment are devoted to their children and motivated to seek treatment as a means of better caring for their children and of setting a good example for their children.

Women faced several challenges for recovery that have been reported in other studies, such as easy access to drugs and alcohol, having family members who still use substances, and having a partner who uses drugs and alcohol (11). The results of this study can provide relevant information for the development of a treatment/intervention that reduce the barriers and the challenges experienced to remain in treatment, especially considering the fact that interventions available often fail to address women’s specific needs (36).

Mothers in this study expressed an openness to and a desire for interventions that involve their families. There is an opportunity to serve families affected by maternal drug addiction by capitalizing upon this motivation. This finding is relevant for the development of future interventions that incorporate mothers’ perspectives on their recovery process, especially considering that treatment plans specifically designed to meet women’s needs remain scarce and, in the current economic climate, are being reduced even further (37).

Even though participants described positive attitudes towards family therapy, some of them described cautions/barriers related to the possibility that family therapy could cause conflict, the lack of interest of their families, or the fact that they were far away from their families. These findings are important in the design of interventions among mothers and for providing a better perspective on how to design strategies to incorporate the family and support the women during recovery. Other studies have described similar challenges, especially in relation to lack of engagement of family members in treatment (38).

5.1. Limitations of the Study

Limitations to this study include the sample size and setting. This study targeted a subgroup of mothers in substance abuse treatment who resided in south Florida; therefore, findings cannot be transferred to all mothers in substance abuse treatment who live in the state of Florida or in the United States.

Studies that consider the perspective of women towards family therapy in south Florida were not found in the literature. The findings of this study can contribute to the development of a family-based substance abuse treatment aftercare intervention that might benefit women in substance abuse treatment. In addition, the findings can increase the awareness of the importance of the family in interventions that include women with substance abuse problems. Also, the study provides valuable information about design strategies that motivate women to abstain from using substances.

Cultural competency is crucial in the provision of services; it demonstrates to clients that the health care workers are respectful to their culture, helps to build trust, and reduces stigma (11). Future interventions with mothers in substance abuse should train health care workers, especially mental health nurses in direct contact with these mothers and their families, in cultural competency when providing care. In addition, medical education should increase the cultural component in the curricula of the health care workers, which should be included as a requirement of their continuing education. Such an approach may ensure that families to experience a trusting environment and develop a positive attitude towards therapy.