1. Background

Recently, there has been a reduction in the worldwide rate of suicide (1); however, suicide trends continue to rise in several countries (2). The suicidal behaviors with increasing committed suicide imply serious mental health challenges (2). It is estimated that suicide is the fourth leading cause of death for those aged 15 - 29 years, according to the World Health Organization (3). Furthermore, in 2020, nearly 46,000 individuals died from suicide in the United States (4).

Suicidal theories have been developed to determine critical factors for suicidal behavior (5-15). The traditional approach to suicide is considered suicidal ideation and suicide attempts as unitary constructs. Social isolation, hopelessness, shame, psychache, and escape from frustrating self-awareness are characterized as predictors of suicidal behaviors (5-12). In contrast to traditional theories, the ideation-to-action framework suggests that suicidal ideation and suicide attempts are separate phenomena with different explanations. Joiner’s interpersonal theory of suicide, as the first theory based on the ideation-to-action framework (13), was a significant advance in suicide studies. According to interpersonal needs theory, a low level of belongingness and a high level of burdensomeness can lead to a tendency for suicidal ideation, and a high acquired capability facilitates suicidal attempts (13, 16).

Another critical theory based on this framework is the integrated motivational-volitional (IMV) model (17, 18). Pre-motivational phase, motivational phase, and volitional phase are the three phases of suicidal behavior formation based on the IMV model. The pre-motivational phase consists of background agents (e.g., diathesis and environment) and triggering events (e.g., relationship crisis) in a biosocial background of suicide. The motivational phase suggests that an individual’s intention to commit suicide is identified by feelings of entrapment, and feelings of defeat/humiliation are indicators of entrapment. Finally, suicide attempts occur in the volitional phase. Stage-specific moderators (i.e., factors that facilitate or impede movement between stages) determine progression from defeat/humiliation to entrapment (i.e., threat-to-self moderators), entrapment to suicidal ideation (i.e., motivational moderators), and suicidal intent to suicidal behavior (i.e., volitional moderators) (14, 19).

Threat-to-self moderators and motivational moderators have a significant role in the IMV model (19). Based on O’Connor and Kirtly, coping skills have been suggested as threat-to-self moderators (19). Although suicide risk is poorly studied in coping skills, there have been some promising findings (17). There is evidence that maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies (e.g., self-blame, other-blame, focus on thought/rumination, and catastrophizing) are associated with suicidal ideation (20). Despite the aforementioned finding, no study has been conducted on how these strategies might lead to the development of suicide intentions according to the IMV model. Therefore, as part of the current study, we set out to clarify how maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies contribute to suicidal ideation formation.

Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are the main causes of suicidal ideation formation (13, 15). Consistent with this finding, these constructs are included as motivational moderators between entrapment and suicidal ideation in the present study.

Although the previous findings of structural tests according to the IMV model are promising (21), they have not included the interactions between latent variables. By using the interaction of latent variables, it was possible to estimate relationship values closer to their actual values (18).

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aimed to test the motivational phase of the IMV model using structural equation modeling (SEM) by exploring the interaction of latent variables. Motivational phase validation in Iran could contribute to improved assessment tools and therapeutic interventions for suicidal ideation among Iranian clinicians.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

In order to test the study model, 405 individuals (68.6% female) with a mean age of 22.7 years (standard deviation: 3.97; range: 17 - 55) completed the study questionnaires. Regarding marital status, the sample was mainly single (84%). The remaining participants were in a relationship (8.1%), married (7.4%), and divorced (0.5%).

Furthermore, 35.1% of the participants reported some psychological problems in the past, and 28.4% stated a history of psychological problems in their family. Regarding the history of self-harm, 14.6% reported self-injurious behaviors. Finally, 5.7% of the participants reported a history of suicidal attempts, and 53% endorsed that they had suicidal ideation.

3.2. Measurements

The Gilbert and Allan Defeat Scale: Is a 16-item that assesses feelings of defeat within the past week. Participants’ responses to each item are scored based on a 5-point Likert (0 = never to 4 = always/all the time). The high scores are correlated with a high level of depression. Gilbert and Allan have demonstrated that the defeat scale has good to excellent psychometric properties (22). The internal consistency of the Persian version was obtained at 0.91 (23).

The Entrapment Questionnaire: Is a 16-item scale created by Gilbert and Allan in 1998. This scale assesses the feeling of entrapment through external entrapment (the first 10 items) and internal entrapment (the last 6 items). Respondents are asked to reveal on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all like me to 4 = extremely like me) how much they are experiencing each statement. According to Gilbert and Allan’s study, Cronbach’s alpha values in the student group for the internal entrapment subscale and external entrapment subscale were obtained at 0.93 and 0.88, respectively (22). The internal consistency of the Persian version was excellent (α = 92) (24).

The Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI): Was created by Beck et al. in 1979. The BSSI includes 19 items and three factors. This scale has five screening items; if the participant’s score in these items is above 0, he/she must complete the entire scale. Each item is scored from 0 to 2. Therefore, the possible range of the total score is 0-38. Beck et al. showed that the BSSI has good psychometric properties (25). The present study used the Persian version of the BSSI, and Cronbach’s alpha for this version was high (α > 0.8) (26).

Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire-short (CERQ-short): Is a self-report, 18-item questionnaire designed by Garnefski and Kraaij in 2006. The aim of CERQ-short is to assess the nine cognitive emotion regulation strategies (i.e., positive refocusing, planning, positive reappraisal, putting into perspective, acceptance, self-blame, other-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing). The CERQ-short measures these strategies on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = never to 5 = almost in the specific subscale. Each subscale includes two items of all 18 items. The highest score of each subscale indicates the more a strategy is used. The reliability and validity were supported (27). The current study utilized the Persian version of the CERQ-short, and the internal consistency of subscales was reported within the range of 0.73 - 0.90 (28).

Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-15 (INQ-15): Is a part of Joiner’s interpersonal needs theory (13), were assessed using a 15-item version of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ-15). The INQ-15 was created to measure the feeling of burden to others (i.e., burdensomeness) and the feeling of connectedness to others (i.e., belongingness). Respondents indicate the degree of these feelings on a 7-point Likert scale (29, 30). The INQ-15 demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, and confirmatory factor analyses showed that this version of the questionnaire has the maximum consistent model fit (30, 31). The present study used the Persian version of the INQ-15, and internal consistency for belongingness and burdensomeness was reported as 0.90 and 0.85, respectively (32).

3.3. Procedure

The study procedure was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Vice-Chancellor in Research Affairs, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The study participants were recruited via social media posting on Telegram and Instagram. Additionally, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences advertised the study on its online platforms. The participants were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary and signed a written consent form. Afterward, the participants completed the study questionnaires online via a web link.

3.4. Data Analysis

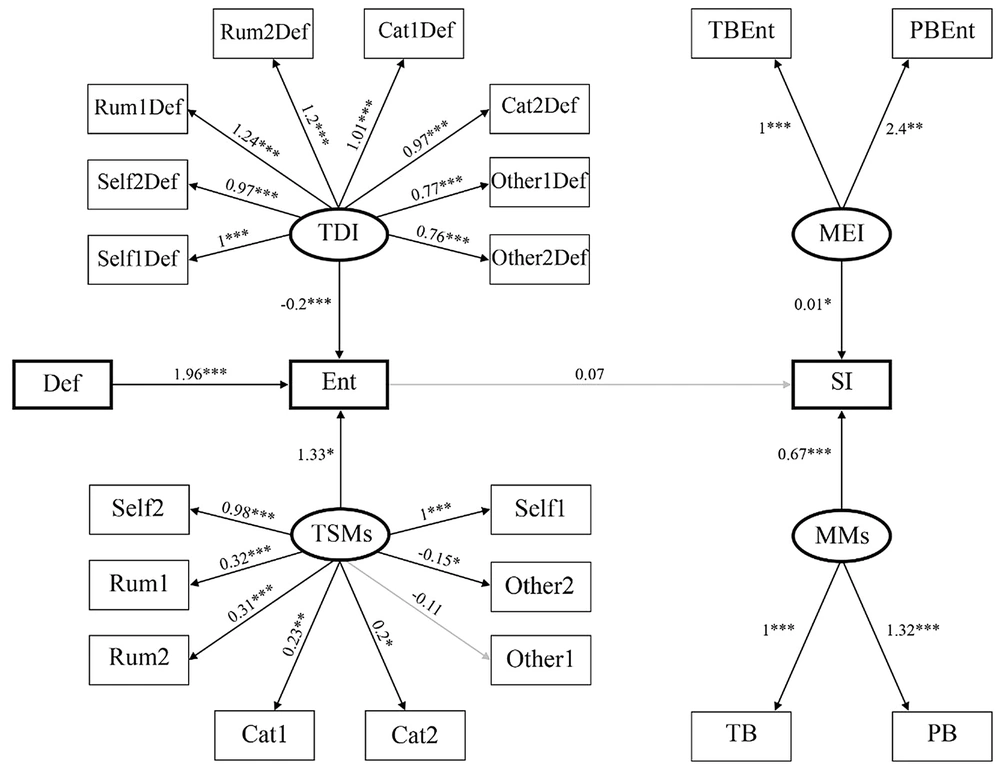

First, we searched for missing data and figured out that there was no missing data. Then, the distribution of variables was checked for deviation from normality, and it was demonstrated that the variables deviated from normality. Therefore, the maximum likelihood with robust standard errors (MLR) estimator was used instead of the popular maximum likelihood to estimate model parameters. The MLR estimator is a good choice when data distributions are not normal, and the sample size is relatively small. Correlations between the variables were also scrutinized to be proper for SEM. Then, SEM was implemented to assess the hypothesized relationships as mentioned in the IMV model. Additionally, the present study explored the effects of treat-to-self moderators and defeat interaction on entrapment and motivational moderators and entrapment interaction on suicidal ideation (Figure 1) (18). All analyses were performed in R environment version 4.1.3 and mainly using the lavaan package (33, 34).

Structural path coefficients of integrated motivational-volitional model. Abbreviations: Def, defeat; Ent, entrapment; SI, suicidal ideation; TSMs, threat-to-self moderators; MMs, motivational moderators; TDI, threat-to-self moderators and defeat interaction; MEI, motivational moderators and entrapment interaction; Self1, item 1 of self-blame; Self2, item 2 of self-blame; Rum1, item 1 of rumination; Rum2, item 2 of rumination; Cat1, item 1 of catastrophizing; Cat2, item 2 of catastrophizing; Other1, item 1 of other-blame; Other2, item 2 of other-blame; TB, burdensomeness; PB, belongingness; Self1.Def, item 1 of self-blame and defeat interaction; Self2.Def, item 2 of self-blame and defeat interaction; Rum1.Def, item 1 of rumination and defeat interaction; Rum2.Def, item 2 of rumination and defeat interaction; Cat1.Def, item 1 of catastrophizing and defeat interaction; Cat2.Def, item 2 of catastrophizing and defeat interaction; Other1.Def, item 1 of other-blame and defeat interaction; Other2.Def, item 2 of other-blame and defeat interaction; TB.Ent, burdensomeness and entrapment interaction; PB.Ent, belongingness and entrapment interaction. Note: All coefficients are non-standard.

The chi-square goodness of fit test, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucke-Lewis index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) as recommended by Kline were used to assess model fit (35). A chi-square test significance value greater than 0.05 shows preliminary support for the hypothesized model. The RMSEA less than 0.06 and upper confidence interval not greater than 0.10 indicate adequate fit. The CFI and TLI greater than 0.95 indicate a good fit. An SRMR less than 0.08 is considered an acceptable fit (36).

4. Results

Table 1 shows the correlations between variables and other descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation. Cronbach’s alpha was also reported for the variables that were used as manifests in the model, either as a scale or subscale.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Mean ± SD | Α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Def | – | 41.92 ± 8.21 | 0.79 | |||||||||||

| 2. Ent | 0.73 ** | – | 17.64 ± 16.46 | 0.96 | ||||||||||

| 3. SI | 0.66 ** | 0.69 ** | – | 4.79 ± 6.30 | 0.86 | |||||||||

| 4. Self1 | 0.05 | 0.13* | 0.02 | – | 3.24 ± 1.11 | - | ||||||||

| 5. Self2 | 0.1 * | 0.16 ** | 0.05 | 0.87 ** | – | 3.06 ± 1.11 | - | |||||||

| 6. Rum1 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.31 ** | 0.28 ** | – | 3.88 ± 0.99 | - | ||||||

| 7. Rum2 | 0.24 ** | 0.3 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.59 ** | – | 3.60 ± 1.09 | - | |||||

| 8. Cat1 | 0.31 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.2 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.39 ** | – | 2.93 ± 1.13 | - | ||||

| 9. Cat2 | 0.36 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.12 * | 0.15 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.44 ** | 0.76 ** | – | 2.73 ± 1.19 | - | |||

| 10. Other1 | 0.24 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.18 ** | -0.13 * | -0.09 * | -0.04 | 0.15 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.36 ** | – | 2.35 ± 1.01 | - | ||

| 11. Other2 | 0.21 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.17 ** | -0.17 ** | -0.14 ** | -0.06 | 0.16 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.82 ** | – | 2.34 ± 1.02 | - | |

| 12. TB | 0.5 ** | 0.6 ** | 0.58 ** | 0.07 | 0.11 * | -0.03 | 0.13 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.24 ** | – | 12.25 ± 8.63 | 0.94 |

| 13. PB | 0.53 ** | 0.6 ** | 0.54 ** | -0.01 | 0.05 | -0.01 | 0.13 ** | 0.2 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.5 ** | 29.51 ± 11.78 | 0.88 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; Def, defeat; Ent, entrapment; SI, suicidal ideation; Self1, item 1 of self-blame; Self2, item 2 of self-blame; Rum1, item 1 of rumination; Rum2, item 2 of rumination; Cat1, item 1 of catastrophizing; Cat2, item 2 of catastrophizing; Other1, item 1 of other-blame; Other2, item 2 of other-blame; TB, burdensomeness; PB, belongingness.

a Statistical significance: * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Using the statistics mentioned earlier, the overall model’s fit was checked. The chi-square test showed a significant value (χ2 (223) = 2916.26, P < 0.001), which indicated that the overall fit of the model was poor. Consistent with this finding, the poorly fitted model was also confirmed by other fit indices (CFI = 0.610, TLI = 0.558, SRMR = 0.264, RMSEA = 0.173 (95% CI: 0.168 - 0.177)). According to the findings of this study, the model accounted for 61% and 70% of variances in suicidal ideation and entrapment, respectively.

Local fit indexes, including standard regression parameters and standard factor loadings, are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

| Β | SE | Z | P | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||||

| Ent | ~ | Def | 0.803 | 0.015 | 52.528 | < 0.001 | 0.773 | 0.832 |

| Ent | ~ | TSMs | 0.069 | 0.033 | 2.073 | 0.038 | 0.004 | 0.134 |

| Ent | ~ | TDI | -0.238 | 0.049 | -4.867 | < 0.001 | -0.334 | -0.142 |

| SI | ~ | Ent | 0.237 | 0.19 | 1.246 | 0.213 | -0.136 | 0.61 |

| SI | ~ | MMs | 0.738 | 0.092 | 7.992 | < 0.001 | 0.557 | 0.919 |

| SI | ~ | MEI | 0.255 | 0.087 | 2.917 | 0.004 | 0.084 | 0.426 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; Def, defeat; Ent, entrapment; SI, suicidal ideation; TSMs, threat-to-self moderators; MMs, motivational moderators; TDI, threat-to-self moderators and defeat interaction; MEI, motivational moderators and entrapment interaction.

| Β | SE | Z | P | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | |||||||

| TSMs | =~ | Self1 | 0.936 | 0.021 | 43.887 | < 0.001 | 0.895 | 0.978 |

| TSMs | =~ | Self2 | 0.921 | 0.02 | 45.829 | < 0.001 | 0.882 | 0.96 |

| TSMs | =~ | Rum1 | 0.334 | 0.054 | 6.168 | < 0.001 | 0.228 | 0.441 |

| TSMs | =~ | Rum2 | 0.299 | 0.061 | 4.921 | < 0.001 | 0.18 | 0.418 |

| TSMs | =~ | Cat1 | 0.208 | 0.068 | 3.039 | 0.002 | 0.074 | 0.342 |

| TSMs | =~ | Cat2 | 0.171 | 0.07 | 2.443 | 0.015 | 0.034 | 0.309 |

| TSMs | =~ | Other1 | -0.109 | 0.073 | -1.497 | 0.134 | -0.252 | 0.034 |

| TSMs | =~ | Other2 | -0.158 | 0.074 | -2.141 | 0.032 | -0.302 | -0.013 |

| MMs | =~ | TB | 0.715 | 0.042 | 17.232 | < 0.001 | 0.634 | 0.797 |

| MMs | =~ | PB | 0.692 | 0.033 | 21.006 | < 0.001 | 0.627 | 0.756 |

| TDI | =~ | Self1.Def | 0.937 | 0.017 | 55.481 | < 0.001 | 0.904 | 0.97 |

| TDI | =~ | Self2.Def | 0.939 | 0.016 | 57.793 | < 0.001 | 0.907 | 0.971 |

| TDI | =~ | Rum1.Def | 0.971 | 0.007 | 140.514 | < 0.001 | 0.958 | 0.985 |

| TDI | =~ | Rum2.Def | 0.978 | 0.004 | 231.676 | < 0.001 | 0.97 | 0.987 |

| TDI | =~ | Cat1.Def | 0.96 | 0.007 | 129.027 | < 0.001 | 0.946 | 0.975 |

| TDI | =~ | Cat2.Def | 0.949 | 0.008 | 112.155 | < 0.001 | 0.932 | 0.965 |

| TDI | =~ | Other1.Def | 0.922 | 0.012 | 77.685 | < 0.001 | 0.898 | 0.945 |

| TDI | =~ | Other2.Def | 0.916 | 0.012 | 75.756 | < 0.001 | 0.892 | 0.94 |

| MEI | =~ | TB.Ent | 0.84 | 0.04 | 20.988 | < 0.001 | 0.761 | 0.918 |

| MEI | =~ | PB.Ent | 0.97 | 0.041 | 23.909 | < 0.001 | 0.89 | 1.049 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; TSMs, threat-to-self moderators; MMs, motivational moderators; TDI, threat-to-self moderators and defeat interaction; MEI, motivational moderators and entrapment interaction; Self1, item 1 of self-blame; Self2, item 2 of self-blame; Rum1, item 1 of rumination; Rum2, item 2 of rumination; Cat1, item 1 of catastrophizing; Cat2, item 2 of catastrophizing; Other1, item 1 of other-blame; Other2, item 2 of other-blame; TB, burdensomeness; PB, belongingness; Self1.Def, item 1 of self-blame and defeat interaction; Self2.Def, item 2 of self-blame and defeat interaction; Rum1.Def, item 1 of rumination and defeat interaction; Rum2.Def, item 2 of rumination and defeat interaction; Cat1.Def, item 1 of catastrophizing and defeat interaction; Cat2.Def, item 2 of catastrophizing and defeat interaction; Other1.Def, item 1 of other-blame and defeat interaction; Other2.Def, item 2 of other-blame and defeat interaction; TB.Ent, burdensomeness and entrapment interaction; PB.Ent, belongingness and entrapment interaction.

The effects of all regressors of entrapment were significant (P < 0.05). The primary effects of defeat and threat-to-self moderators were positively related to entrapment; nevertheless, the primary effect of threat-to-self moderators and defeat interaction was negatively related to entrapment. Furthermore, motivational moderators and motivational moderators and entrapment interaction were significant predictors of suicidal ideation (P < 0.05). However, entrapment did not reach the conventional significance value (P < 0.05). Two interaction terms showed relatively moderate effects. The most effective variable to predict suicidal ideation as the ultimate endogenous variable in the model (Figure 1) was the motivational moderator’s factors, and their effect size was moderate-high.

5. Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the motivational phase of the IMV model using SEM with the interaction of latent variables. Overall, the obtained results indicated that the model was a poor fit for the data. However, the model explained the considerable amount of variance between entrapment and suicidal ideation; nevertheless, the findings demonstrated that the pathway between entrapment and suicidal ideation was not statistically significant.

Furthermore, the results of the interaction between the suicidal ideation predictors showed that the interaction between defeat and threat-to-self moderators had a negatively significant effect on the relationship between defeat and entrapment. Additionally, the interaction between entrapment and motivational moderators had a positively significant effect on the relationship between entrapment and suicidal ideation. Previous studies have shown that exploring the interaction of latent variables results in more study power and less biased estimation (18, 37). The main result of the interaction between the suicidal ideation predictors was the predictive role of entrapment and motivational moderators in suicidal ideation. In the following, we discuss the probable explanation for this finding.

In line with previous studies, this study found a significant relationship between defeat and entrapment. It has been shown that defeat and entrapment are associated with several psychopathological symptoms (22, 38, 39). The appraisal of defeat and a sense of entrapment are the main components of the cry of pain theory. This theory conceptualizes suicide as a behavioral response to a frustrated and painful situation. Defeat, no escape, and no rescue are three elements of the behavioral response. Due to the appraisal of defeat, individuals might experience more entrapment and decrease the escape level (12). In the current study, the presence of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies contributes to a sense of entrapment. These strategies, for example, rumination, serve as tunnel cognition or cognitive deconstruction (40) in a way that the individual cannot see the way to escape from the defeated situation, and the feeling of entrapment emerges (19).

The current study’s results unexpectedly demonstrated that there was no significant relationship between entrapment and suicidal ideation. In other words, entrapment cannot mediate between defeat and suicidal ideation. This finding is consistent with the findings of Ng et al. (41) and Taylor et al. (42). Nevertheless, according to the cry of pain theory (12) and the IMV model (19), the violation of entrapment’s centrality in the formation of suicidal intent is a controversial finding. The small sample size and the low level of suicidal desire (53%) in the total sample could be two explanations for this finding.

In addition, O’Conner and Portzky have suggested that entrapment can be a cultural, gender-sensitive, and age-sensitive concept (43). In this regard, the present study also suggests that entrapment might be a situation-sensitive concept or temporary condition. Consequently, although the individuals report a feeling of entrapment, they remain optimistic and hopeful that a way out will appear and reject suicidal ideation as a solution (42). To this finding and based on the moderating effect of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies between defeat and entrapment, probably the severity and frequency of using these strategies could also be an important factor in the relationship between entrapment and suicidal ideation. Optimistic views about the future and hopefulness are associated with further adaptive strategies (26).

Another important result of the current study was the significant relationship between motivational moderators (i.e., thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) and suicidal ideation. This finding is consistent with the main idea of interpersonal needs theory. Based on Joiner’s theory, a lack of social connectedness is remarkable in forming a desire for death (13, 16). According to this theory, other risk factors (e.g., hopelessness, shame, and psychache) might influence suicidal ideation by increasing feelings of thwarted belongingness or perceived burdensomeness or a combination of the two (16). Furthermore, Durkheim has suggested that social isolation is a significant factor in the development of suicidal ideation (11).

Additionally, the interaction of entrapment and motivational moderators was a prominent predictor of suicidal ideation. Therefore, the interactive effect of entrapment and lack of social connectedness is the important proximal predictor of suicidal ideation. Probably, in such a situation, optimistic views about a solution will be ruined, and the interaction between a sense of entrapment and loneliness results in suicidal intent. In addition, as noted above, entrapment and social factors are significant elements in contemporary suicidal theories. Therefore, the predictive effect of the interaction of these elements is consistent with present knowledge about suicide.

The results of the current study should be considered in light of some limitations. Firstly, all of the results are cross-sectional. Longitudinal data will be beneficial for searching the causality. Secondly, the assessment of suicidal ideation was conducted by self-reporting questionnaires. Future studies should employ methods other than self-reporting, such as interviews. Thirdly, the cry of pain theory (12) and the IMV model (19) include humiliation as a predictor of entrapment. In this study, only the role of defeat was explored. Therefore, investigating the role of humiliation besides defeat is an important direction for future studies. Fourthly, considering the prevalence of suicide attempts in the general population (44), investigating the pre-motivational factors and volitional moderators according to exploring the interaction of latent variables method is necessary. Fifthly, probably other theories based on the ideation-to-action framework, such as interpersonal needs theory (13) and three-step theory (15), can better explain suicidal ideation in the Iranian population. Therefore, our understanding of suicidality in this population can be improved by assessing suicidal ideation according to these theories. Finally, generalizability is limited since all the participants of the study were students. Consequently, it would be helpful to replicate the results in a different population.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present study was designed to investigate the motivational phase of the IMV model using SEM by the interaction of latent variables. The findings suggest that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are the most effective predictors of suicidal ideation in the Iranian population. To the best of our knowledge, the current study was the first study according to the ideation-to-action theories of suicidality by exploring the interaction of latent variables. Hopefully, this study will encourage further studies in this area.