1. Background

Rapid technological developments have greatly lifted people’s access to the Internet (1). The increase in the use of the Internet and the widespread use of mobile phone applications have also made social media more popular (2). People often visit social media for entertainment and social activities such as gaming, socializing, communicating, and sharing images (3). Online applications such as social media allow people to expand activities such as interacting with others, safeguarding relationships, and forming interest groups (4). Although there is optimism about the facilitative power of new technologies, these technologies may cause people to lose the balance between the real and virtual worlds. Internet-based technologies have become an integrated part of and made our lives easier via various programs or applications (5). Meanwhile, studies have shown that the uncontrolled and excessive use of social media is associated with addiction (6). For this reason, many researchers have considered the excessive use of social media as a behavioral addiction (2, 4). The Internet facilitates individuals’ lives, for example, by expanding social communication and obtaining and sharing information, but its addictive and pathological use can adversely affect people’s physical and mental health, as well as their familial and social life, especially among adolescents (7). The excessive use of social media affects users’ feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, gradually causing them to spend more time on social media. Therefore, when these people are disconnected from these media, they are likely to experience unpleasant feelings (2). Due to adolescents’ interest in cyberspace, they tend to use the Internet and social media more frequently (8), raising concerns about the adverse impacts of this environment on their health and behavioral development (9). Keles et al. (10) stated that 92% of adolescents are actively engaged with social media.

Adolescents usually seek more independence and freedom, but due to their vulnerabilities in this period, parents tend to adopt a more controlling strategy and supervise them more frequently, occasionally leading to parent-adolescent conflict (11). Parent-adolescent conflict is one of the factors contributing to the emergence of emotional and behavioral problems (12). Adolescents’ tendency to browse social networks and find friends there can make them develop a dependence on the Internet (13), leading them to stay online more than usual, worrying their parents (14). For this reason, some studies have focused on the relationship between social media addiction and familial conflicts. Many studies have highlighted that the quality of the parent-adolescent relationship is closely related to the frequency of social media use by adolescents, and parent-adolescent conflict can make adolescents spend more time in the conflict-free environment of social media instead of spending time with their family members (15-17).

According to researchers, parents, as the first social source influencing children, can play an important role in protecting adolescents from developing social media addiction (18). Perceived parental psychological control is one of the family-related factors directly associated with social media addiction (19). Intense parental psychological control negatively affects children’s sense of independence, identity, and competence, causing them painful experiences such as insecurity and feelings of being ignored and isolated (20). In such situations, children tend to look for alternatives, including cyberspace, to mitigate their bad feelings or avoid adversities (21). Many studies have emphasized that psychological control and extremely intrusive and authoritarian parenting styles are positively correlated with children’s social media addiction (17). Besides, parental psychological control can trigger the problematic use of cyberspace among adolescents (22).

2. Objectives

Considering the role of parent-adolescent relationships and parental psychological control in adolescents’ tendency towards high-risk behaviors, the present study addresses the predictive value of parent-adolescent conflict and parental psychological control by analyzing two groups of adolescents (i.e., with and without social media addiction).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Setting and Population

This descriptive-correlational study was conducted using discriminant analysis to explore social media addiction among 13-18-year-old female adolescents in Ahvaz city in 2022. This population was selected for this research due to the fact that adolescents tend to frequently use cyberspace, which was even exaggerated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research sample population included 682 adolescents, who were selected using voluntary sampling and divided into two groups based on the presence (n = 103) or absence (n = 103 out of 579 adolescents) of social media addiction. Then, discriminant analysis was conducted with equal groups based on the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale at a cut-off score of 24 (i.e., scores higher than 24 to identify people with social media addiction) (21). Due to the unavailability of the population variance, Krejcie and Morgan’s table was used to select the sample size as a method suggested when the population variance is not available. Meyers et al. recommended the smallest sample size for each group to be between 10 and 20 cases per predictor (20, 23).

Inclusion criteria were willingness to participate in the research, parenting at least one 13-18-year-old child, and living in the city of Ahvaz. The data were collected online after preparing an electronic version of the instruments, and respective links were posted on different online social media and networks for parents of children studying in elementary schools. Volunteers were then asked to click on the link and answer the questions. Ethical considerations were observed, including ensuring voluntary participation, respecting respondents’ privacy, and keeping their information confidential.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale

The Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale was adapted from the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale developed by Andreassen et al. (24). This 9-item instrument measures 6 main characteristics of addiction (salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, and relapse). The items on this tool are scored using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very rare) to 5 (often). Luo et al. (4) introduced a score of 24 as a suitable cut-off point to identify people with social media addiction. In the present study, the reliability of this scale was confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77.

3.2.2. Parent-Adolescent Conflict Scale-Short Form

This scale was developed by Prinz et al. (25). Originally, it had 75 items to measure the perception of adolescents on the degree of conflict with their parents. In this study, the 20-item short form of the scale was used, consisting of two separate versions for the father and the mother to measure the severity of their conflict with adolescents. The items are answered by expressing either agreement (1) or disagreement (2). In the present study, the reliability of this scale was confirmed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.92 (for conflict with the mother) and 0.91 (for conflict with the father).

3.2.3. Psychological Control Scale

This scale was developed by Barber (26) to measure the level of parental psychological control perceived by adolescents. This scale contains 16 items, 8 of which measure the father’s psychological control, and the other 8 items assess the mother’s psychological control. This scale measures parental behaviors that hinder adolescents’ autonomy, self-expression, and independence, including constraining verbal expressions, pressuring the child to submit, invalidating feelings, personal attacks on the child, guilt induction, and love withdrawal. The items on the scale are scored on a 3-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not like her/him) to 3 (a lot like her/him). In the present study, the reliability of this scale was confirmed based on Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical methods were conducted in SPSS 25 software using descriptive statistics, correlation coefficients, and discriminant analysis.

4. Results

The means of age of participants with and without social media addiction were 15.18 ± 1.66 and 15.09 ± 1.63 years, respectively. The mean scores of maternal conflict, paternal conflict, and parental psychological control were significantly different between the two groups of adolescents (i.e., with and without social media addiction), with higher scores gained by adolescents with social media addiction (Table 1).

| Predictor Variables | Mean ± SD | Correlation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group with SMA | Group Without SMA | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1. Conflict with the mother | 5.61 ± 5.47 | 2.32 ± 3.27 | 1 | ||

| 2. Conflict with the father | 6.53 ± 5.50 | 2.27 ± 3.40 | 0.46 | 1 | |

| 3. Parental psychological control | 29.56 ± 6.94 | 23.33 ± 5.45 | 0.65 | 0.63 | 1 |

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Between the Studied Variables

Wilks’ lambda (WL = 0.76) and a high chi-square value (χ2 = 108.67), which were statistically significant (P < 0.001), indicated that the functions (i.e., conflict with the mother, conflict with the father, and parental psychological control) had good discriminant power to explain the variance of the criterion variable (i.e., social media addiction) and could differentiate adolescents with and without social media addiction (Table 2).

| Indicators | Number of Functions | Eigenvalue | Variance (%) | Canonical Correlation | Eta Square | Wilks Lambda | Chi-square | df | Significance of the Discriminant Function | Data Centroid | Accuracy in Predicting Group Membership | Kappa Coefficient | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | No SMA | |||||||||||||

| Values | 1 | 0.30 | 100 | 0.48 | 0.23 | 0.76 | 108.67 | 3 | 0.001 | 0.551 | -0.551 | 72.8% | 0.45 | 0.001 |

The Results of Conventional Discriminant Function

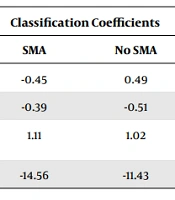

According to the standard coefficients, parental psychological control, with a standard coefficient of β = 0.52, had more power in differentiating between adolescents with and without social media addiction, followed by paternal conflict (with a coefficient of β = 0.47). Maternal conflict had lower predictive power than the two former variables, with a coefficient of β = 0.19. The predictive direction of all three variables was positive (Table 3).

| Predictor Variables | Standard Coefficients | Non-standard Coefficients | Structural Coefficients | Classification Coefficients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | No SMA | ||||

| Conflict with the mother | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.90 | -0.45 | 0.49 |

| Conflict with the father | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.84 | -0.39 | -0.51 |

| Parental psychological disorder | 0.52 | 0.08 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 1.02 |

| Constant | -2.84 | -14.56 | -11.43 | ||

Standard, Non-standard, Structural, and Classification Coefficients

The results of the mean equality test were statistically significant (P < 0.001) for the two groups based on Wilks’ lambda coefficient (WL = 0.88, 0.82, and 0.80), F-value (F = 55.05, 89.09, and 102.49) (Table 4).

| Scales | Wilks’ Lambda | F-Value | df1 | df2 | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conflict with the mother | 0.88 | 55.05 | 1 | 410 | 0.01 |

| Conflict with the father | 0.82 | 89.09 | 1 | 410 | 0.01 |

| Parental psychological disorder | 0.80 | 102.49 | 1 | 410 | 0.01 |

The Mean Equality Test for Adolescents with and Without Social Media Addiction

Given the small Wilks’ lambda value and the statistically significant level (P < 0.001), the functions of conflict with the mother, conflict with the father, and parental psychological control were significantly able to explain social media addiction as the dependent variable and differentiate between adolescents with or without social media addiction (Table 5).

| Indicators | Number of Functions | Eigenvalue | Variance (%) | Canonical Correlation | Wilks Lambda | Chi-square | df | Significance of the Discriminant Function | Non-standard Coefficient | Constant | Kappa Value | Sig. | Data Centroid | Accuracy in Predicting Group Membership | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA | No SMA | ||||||||||||||

| Conflict with the mother | 1 | 0.13 | 100 | 0.34 | 0.88 | 51.29 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.22 | -0.88 | 0.29 | 0.001 | 0.366 | -0.366 | 64.6% |

| Conflict with the father | 1 | 0.21 | 100 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 80.52 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.21 | -0.96 | 0.35 | 0.001 | 0.465 | -0.465 | 67.5% |

| Parental psychological disorder | 1 | 0.25 | 100 | 0.44 | 0.80 | 91.30 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.16 | -4.23 | 0.39 | 0.001 | 0.499 | -0.499 | 69.7% |

The Results of Discriminant Analysis

5. Discussion

The present study investigated whether parent-adolescent conflict and parental psychological control could predict adolescents’ social media addiction. The results indicated that parent-adolescent conflict, including maternal and paternal conflict, could reliably predict adolescents’ social media addiction and differentiate between adolescents with and without social media addiction, supporting previous studies on this topic (12, 15-17, 27). The presence of conflict and problems in the family provides more motivation for adolescents to use social media, which may lead to addiction. Usually, adolescents have difficulty expressing their emotions, leading them to feel alone and, therefore, turn toward the Internet and social media to escape from the real world. Among the reasons encouraging adolescents to excessively use the Internet are enthusiasm for browsing social networks, finding friends, seeking entertainment, and relieving stress (28). Abnormal family functioning is one of the factors contributing to adolescent-parent conflict.

Conflict between parents may cause adolescents to be engaged in these conflicts and baffle them as they do not know whether to support the father or the mother (9). The adolescent hates this situation and thus resorts to the excessive use of social media to get rid of this unpleasant situation. A review of the literature shows that during familial conundrums, the time spent on social media by adolescents increases, and as a result, they are more likely to develop social media addiction (29). Parental conflict and the lack of parental support for adolescents make them use interactive experiences and seek social support online, and unfortunately, the excessive use of the Internet by adolescents usually aggravates their conflict with parents, making social media addiction more difficult to resolve (9). Parent-adolescent conflict can dispirit the relationship between these two sides, and as a result, the adolescent avoids establishing a relationship with their parents. Consequently, the adolescent seeks alternatives to communicate with, including friends and peers, to fill this gap. In this situation, communication often takes place online through social media, where adolescents spend a lot of time communicating with their friends and finding more friends to interact with. They usually do not run into conflict in these media, where they will gain the acceptance that is sometimes withheld from their parents.

The findings of this study also indicated parental psychological control can predict adolescents’ social media addiction and distinguish between adolescents with or without social media addiction, as confirmed in previous studies (5, 19, 22, 30). A direct path is visible between parental psychological control and all technology-related addictions (e.g., the Internet, games, smartphones, and social networks) (30). Parental psychological control interferes with the fulfillment of the adolescent’s independence needs, and the higher the level of this control, the higher the level of parent-adolescent conflict, making them avoid each other. Under such conditions, adolescents use social media to escape from parental control and gain more independence and psychological freedom.

5.1. Conclusions

The present study showed that parent-adolescent conflict and parental psychological control could plausibly predict adolescents’ social media addiction and differentiate between adolescents with or without social media addiction. These findings can expand our understanding of adolescents’ social media addiction. An adolescent’s conflict with his/her parents and parental psychological control can destabilize the relationship between them, encouraging the adolescent to replace the relationship with social media through compensatory behaviors. Accordingly, the more intense the conflict with parents and their psychological control, the higher the possibility of social media addiction among adolescents. The findings of this study showed that systematic interventions and changing family interaction patterns could be effective strategies for preventing and treating cyberspace addiction among adolescents. The use of a non-random sampling method can be one of the limitations of this study. Besides, the economic status and the education level of parents can be among the factors influencing our results. Therefore, it is suggested to control or investigate these variables in future studies. Accordingly, similar studies can be conducted in other age groups and boys to assess the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, social media addiction can be assessed using other techniques, such as interviews.