1. Background

Using pornography via the internet is now a common activity (1) that varies according to gender, age, relationship status, and sexual orientation (2). It is currently estimated that 25% to 30% of all data transmitted over the internet is pornography (3-7). Pornography websites are among the top 50 most visited websites worldwide (8); according to a survey by PornMD, among countries with the most Google searches for sexually explicit content, Iran ranks fourth after Pakistan, Egypt, and Vietnam in this regard (9).

Increasing access to pornography since the advent of the internet provides a new context for couples' sexual experiences. Numerous studies have been conducted on the role of pornography in the satisfaction of intimate relationships, and some findings show that pornography has a negative effect on intimate relationships and causes spousal involvement (10, 11). Various studies have reported a variety of side effects of pornography use, including high-risk sexual behaviors, sexual violence, multiple sexual partners, the possibility of contracting sexually transmitted infections, infidelity, child sexual abuse, drug use, alcohol consumption during sex, and difficulty in establishing intimate emotional relationships (3, 12-16).

Conflicting results have been reported on the relationship between women's use of pornography and their higher sexual satisfaction (17, 18). It seems that women who feel guilty about pornography use have less sexual desire in romantic relationships with their husbands (19). Also, the results of studies on the relationship between female sexual desire and pornography use have been contradictory (20, 21).

Marital satisfaction is an important factor in predicting the continuity of a couple's relationship. In Iranian couples, women are less satisfied with marriage than men (22). Marital satisfaction of Iranian women was related to sexual satisfaction, sexual pleasure, social support, and religious attitudes (23-26). The rate of Iranian women’s pornography use has been reported to be between 17.4% and 35% and has rarely been studied (27, 28). Pornography use may be associated with increased marital separation (29, 30).

Knowledge regarding the effect of pornography use on women's sexual desire and marital satisfaction in romantic relationships is rare and controversial.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to compare sexual desire and marital satisfaction in 2 groups of married women with and without a history of pornography use in Rafsanjan city, Iran, in 2020.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Setting

Iran is located in Southwest Asia and is divided into 31 provinces. The city of Rafsanjan is located in the northwest of Kerman Province in central Iran. According to the 2016 census, the population of Rafsanjan city is estimated at 31 1214 individuals, of whom 14 8491 are women. The official religion of Iran is Shiite Islam, and 99.59% of the people of this country are Muslims (31). According to Islam, watching others’ naked bodies and images has always been considered sinful and forbidden (32). According to the law in Iran, any development, receiving, ownership, and keeping of visual and auditory pornography products are criminalized with the approach of absolute prohibition (33). It seems that using pornography among Iranian youth is becoming a common behavior, although there is no evidence in this regard.

This descriptive study was conducted in Rafsanjan city, Iran, in 2020. The target population of this study includes women with children covered by comprehensive health centers in Rafsanjan. A group of women who were similar in terms of marriage age (date of marriage in 2012 ± 3) were selected and registered in the study.

Inclusion criteria were being Iranian, signing the consent form, being married, having no known history of psychological disorders, having no acute problems in interpersonal relationships with a spouse, having no children under 6 months, having access to smartphones, and having no use of psychiatric drugs and narcotics. The rationale for eliminating women with children under 6 months was the possible effect of pregnancy hormones on sexual desire occurring 6 months after childbirth. Participation in this study was completely voluntary, and all participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Based on a pilot study of 20 people, the required sample size was determined to be 240 people in total. Easy sampling was performed in 3 of the 8 urban centers located in the city center, which was relatively similar in terms of cultural and social status. The Ethics Committee of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences approved this study (code: IR.RUMS.REC.1398.212). Then, a letter of introduction was received from the Vice Chancellor for Research of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, and the sampling was performed after obtaining permission from the head of health centers and coordination with the family health unit.

First, researchers obtained all telephone numbers of eligible women from the family unit of each comprehensive health center. These telephone numbers have already been registered in the Iranian integrated health system (known as the SIB system). Second, the first author, during a 40-day period, contacted all women one by one via telephone calls and invited them to participate in the project. During this period, the first author called 783 women, introduced herself, and explained the aim of the research. Then, she invited them to receive the research link and complete the online questionnaire. Of the 783 invited women, 514 accepted to receive the link and 284 completed the questionnaires. Of the 284 completed questionnaires, 30 were omitted due to not meeting the eligibility criteria and 254 were analyzed.

To maintain privacy, participants were also assured that responses would be gathered anonymously. It was also possible for the participants to express any problem in the questionnaire with the researcher through WhatsApp.

Data collection tools included a demographic characteristics form, Enrich Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire (EMSQ), Hurlbert Index of Sexual Desire (HISD), and pornography questionnaire.

3.2. Research Instruments

3.2.1. Enrich Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire

The Enrich Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire was developed by Olson in 1989 and consists of 115 questions (34). The brief form of this questionnaire contains 47 questions and 9 subscales, including personality issues, marital communication, conflict resolution, financial management, leisure activities, sexual relation, marriage and children, family and friends, and religious orientation (30, 35-39). Larsen and Olson reported the reliability of this questionnaire using Cronbach α at 0.92, as did Hedayati Dana and Saberi in the context of Iran at 0.93 (34, 40). In this study, a 47-item form was used, and reliability was calculated using Cronbach α coefficient of 0.945.

3.2.2. Hurlbert Index of Sexual Desire

Hurlbert Index of Sexual Desire was developed by Hulbert and has been used in various studies worldwide. This questionnaire consists of 25 items that measure women’s sexual desire. This questionnaire has no sub-components, and the total number is 100 on a 5-point Likert scale. Hulbert obtained the reliability of the HISD at 0.86 through the test-retest method. The internal consistency coefficients of the HISD using 2 Cronbach α methods were 0.89, and Yousefi et al validated the instrument in the Iranian context (41, 42). In the present study, reliability was calculated using Cronbach α coefficient of 0.929.

3.2.3. Pornography Questionnaire

The Pornography Questionnaire (SPQ) developed by Jafarzadeh Fadaki and Amani contains 17 questions about the use of different forms of pornography and the quality of pornography use. Each question is scored on a 5-point Likert scale: Never, rarely, sometimes, often, and usually. Participants were divided into 2 groups with and without a history of pornography use based on factor questions 2, 5, and 7 of the pornography questionnaire. These 3 factor questions are as follows: (2) how much do you watch sexual movies and photographs on your cell phone?; (5) how much do you watch sexual video clips on your cell phone?; (7) how frequently do you watch sexual movies on your cell phone or other devices? If the answer to at least 2 of these 3 questions were “never," the participants were considered “without a history of pornography use." The Cronbach α coefficient was 0.75 for this questionnaire (30). In the present study, reliability was calculated using the Cronbach α coefficient of 0.911.

Data were collected by the researcher using SPSS version 21 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA), and the accuracy of data entry into the software was checked. Statistical analysis was performed after coding reverse questions. Independent 2-sample t test, chi-square, and multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) were used to analyze the data. P values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

Of the 254 participants, 94 (37%) had a history of pornography use and 160 (63%) had no history of pornography use. The results of the chi-square test showed that in demographic and social variables, there was no statistical difference between the 2 groups with and without a history of pornography use (Table 1).

| Women with a History of Pornography Use | Women with No History of Pornography Use | Total | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of education | 0.508 | |||

| High school and less | 27 (28.7) | 49 (30.6) | 76 (29.9) | |

| Master | 56 (59.6) | 85 (53.1) | 141 (55.5) | |

| Postgraduate | 11 (11.7) | 26 (16.3) | 37 (14.6) | |

| History of psychiatric visit | 0.283 | |||

| Yes | 5 (5.3) | 13 (8.1) | 18 (7.1) | |

| No | 89 (94.7) | 147 (91.9) | 236 (92.9) | |

| Job status | 0.97 | |||

| Housewife | 67 (71.3) | 116 (72.5) | 183 (72) | |

| Self-employment | 9 (9.6) | 14 (8.1) | 23 (9.1) | |

| Clerk | 18 (19.1) | 30 (18.8) | 48 (18.9) | |

| Quality of the couple’s relationship | 0.36 | |||

| Weak and moderate | 27 (28.7) | 41 (25.6) | 68 (26.8) | |

| Good | 67 (71.3) | 119 (74.4) | 186 (73.2) | |

| Marriage type | 0.877 | |||

| My family’s choice and my agreement | 54 (57.4) | 97 (60.6) | 151 (59.4) | |

| My choice and my family’s agreement | 34 (36.2) | 53 (33.1) | 87 (34.3) | |

| The conflict between me and my family | 6 (6.4) | 10 (6.3) | 16 (6.3) | |

| Habitation after marriage | 0.604 | |||

| With family | 10 (10.6) | 26 (13.8) | 32 (12.6) | |

| Independent | 84 (89.4) | 138 (86.3) | 222 (87.4) | |

| Total | 94 (100) | 160 (100) | 254 (100) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

b Pearson chi-square.

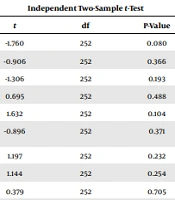

The mean age of women with and without a history of pornography use was 31.45 and 32.26 years, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of age, number of children, duration of marriage, and religiosity. Also, there was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in the mean score of sexual desire, marital satisfaction, and subscales of marital satisfaction, including personality issues, marital relationship, conflict resolution, leisure activities, sexual relationship, marriage and children, family and friends, and religious orientation, between both groups. There was a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups only in the mean of the financial management sub-component (P = 0.046; Table 2).

| Variables | Women with a History of Pornography Use (n = 94) | Women with No History of Pornography Use (n = 160) | Independent 2-Sample t Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | P Value | |||

| Religiosity | 1.74 ± 7.45 | 2.07 ± 7.89 | -1.760 | 252 | 0.080 |

| Number of children | 0.4 ± 1.80 | 0.38 ± 1.84 | -0.906 | 252 | 0.366 |

| Age (y) | 4.84 ± 31.45 | 4.73 ± 32.26 | -1.306 | 252 | 0.193 |

| Number of years of marriage | 3.59 ± 9.37 | 3.66 ± 9.04 | 0.695 | 252 | 0.488 |

| The total score of sexual desire | 18.06 ± 62.18 | 16.55 ± 58.55 | 1.632 | 252 | 0.104 |

| The total score of marital satisfaction | 28.23 ± 160.05 | 30.56 ± 163.51 | -0.896 | 252 | 0.371 |

| Personality issues | 5.63 ± 20.61 | 5.53 ± 19.75 | 1.197 | 252 | 0.232 |

| Marital communication | 5.48 ± 20.61 | 5.92 ± 19.75 | 1.144 | 252 | 0.254 |

| Conflict resolution | 4.31 ± 16.04 | 4.68 ± 15.82 | 0.379 | 252 | 0.705 |

| Financial management | 3.92 ± 19.32 | 4.43 ± 18.21 | 2.005 | 252 | 0.046 |

| Leisure activities | 2.40 ± 16.23 | 2.58 ± 16.01 | 0.679 | 252 | 0.498 |

| Sexual relationship | 3.79 ± 17.91 | 3.97 ± 17.42 | 0.977 | 252 | 0.329 |

| Marriage and children | 3.59 ± 17.55 | 3.87 ± 16.76 | 1.627 | 252 | 0.105 |

| Family and friends | 3.53 ± 17.09 | 4.13 ± 17.16 | -0.152 | 252 | 0.879 |

| Religious orientation | 3.71 ± 19.67 | 3.88 ± 19.63 | 0.078 | 252 | 0.937 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise indicated.

Controlling the effect of the variables of “education level, job status, quality of couple relationship, type of marriage, habitation after marriage, and age" via analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) showed a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in sexual desire, but not in marital satisfaction (Table 3).

| Variables | Total Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Squares | Statistics F | P Value | Squared Eta | Test Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual desire | 4.131 | 0.043 | 0.167 | 0.526 | |||

| Group | 1107.399 | 1 | 1107.399 | ||||

| Error | 64871.103 | 242 | 268.062 | ||||

| Total | 985805.000 | 254 | |||||

| Marital satisfaction | 0.372 | 0.543 | 0.101 | 0.193 | |||

| Group | 203.752 | 1 | 203.752 | ||||

| Error | 132674.937 | 242 | 548.244 | ||||

| Total | 6908389.000 | 254 |

Multivariate analysis of covariance was applied to compare the mean score of the components of marital satisfaction of women with and without pornography use while adjusted for “education level, job status, quality of couple relationship, type of marriage, habitation after marriage, and age."

The Box M test indicated the equality of covariance matrices in the 2 groups (P = 0.39). The Levene test also showed equality of error variances across the 2 groups (P > 0.05). The Shapiro-Wilk test revealed the normality of numeric variables in both groups (P > 0.05). The results of Pillai trace, Wilks Lambda, Hotelling trace, and Roy largest root tests on the difference between the 2 groups in the 9 components of marital satisfaction are significant (P = 0.041). This means that the 2 groups have statistically significant differences with each other in at least one of the 9 components of marital satisfaction.

Multivariate analysis of covariance showed a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups with and without a history of pornography use in the “mean score of the financial management component" (P = 0.037) but not in other components of marital satisfaction (Table 4).

| Variables | Total Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Squares | Statistics F | P Value | Squared Eta | Test Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality issues | 1.455 | 0.0229 | 0.060 | 0.225 | |||

| Group | 45.862 | 1 | 45.862 | ||||

| Error | 665.7625 | 242 | 31.511 | ||||

| Total | 110611.000 | 254 | |||||

| Marital communication | 1.168 | 0.281 | 0.050 | 0.190 | |||

| Group | 39.297 | 1 | 39.297 | ||||

| Error | 583.8138 | 242 | 33.631 | ||||

| Total | 110689.000 | 254 | |||||

| Conflict resolution | 0.157 | 0.692 | 0.010 | 0.068 | |||

| Group | 3.284 | 1 | 3.284 | ||||

| Error | 5055.428 | 242 | 20.890 | ||||

| Total | 69439.000 | 254 | |||||

| Financial management | 4.383 | 0.037 | 0.108 | 0.550 | |||

| Group | 78.884 | 1 | 78.884 | ||||

| Error | 4355.844 | 242 | 17.999 | ||||

| Total | 92700.000 | 254 | |||||

| Leisure activities | 1.821 | 0.178 | 0.070 | 0.269 | |||

| Group | 9.917 | 1 | 9.917 | ||||

| Error | 1317.662 | 242 | 5.445 | ||||

| Total | 67388.000 | 254 | |||||

| Sexual relationship | 0.779 | 0.378 | 0.030 | 0.142 | |||

| Group | 12.158 | 1 | 12.158 | ||||

| Error | 3778.589 | 242 | 15.614 | ||||

| Total | 82559.000 | 254 | |||||

| Marriage and children | 2.891 | 0.090 | 0.070 | 0.395 | |||

| Group | 41.277 | 1 | 41.277 | ||||

| Error | 3455.427 | 242 | 14.279 | ||||

| Total | 77467.000 | 254 | |||||

| Family and friends | 0.006 | 0.937 | 0.009 | 0.051 | |||

| Group | 0.100 | 1 | 0.100 | ||||

| Error | 3804.425 | 242 | 15.721 | ||||

| Total | 78438.000 | 254 | |||||

| Religious orientation | 0.057 | 0.812 | 0.006 | 0560.056 | |||

| Group | 0.838 | 1 | 0.838 | ||||

| Error | 3583.693 | 242 | 14.809 | ||||

| Total | 101708.000 | 254 |

The results of testing skewness and kurtosis of variables showed the normality of variables (Table 5).

| Women with a History of Pornography Use (n = 94) | Women Without a History of Pornography Use (n = 160) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skewness | Kurtosis | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Total satisfaction score | -0.209 | -0.559 | -0.011 | -0.764 |

| Total desire score | -0.566 | -0.057 | -0.364 | -0.297 |

| Personality issues | -0.260 | -0.730 | -0.047 | -0.791 |

| Marital communication | -0.334 | -0.512 | -0.215 | -0.937 |

| Conflict resolution | -0.161 | -0.289 | -0.155 | -0.944 |

| Financial management | -0.489 | -0.256 | -0.450 | -0.359 |

| Pleasure activities | 0.131 | -0.008 | -0.151 | -0.252 |

| Sexual relation | -0.167 | -0.618 | -0.318 | -0.252 |

| Marriage children | -0.027 | -0.474 | 0.160 | -0.625 |

| Family and friends | -0.051 | -0.574 | -0.093 | -0.342 |

| Religious orientation | -0.568 | -0.052 | -0.581 | -0.351 |

5. Discussion

The results of the present study showed that 37% of the subjects had a history of pornography use, while 63% did not. Although in other studies, the use of pornographic products was higher among young adults (30 - 40 years old) (11, 43, 44), in our study, the difference in pornography use in various age groups was not significant; this was consistent with Perry and Schleifer's study (29). In the present study, there was no statistically significant relationship between demographic characteristics of education level, quality of couple relationship, and years of marriage with pornography use, which does not correspond to the results of other studies (11, 43, 45, 46). It seems that the young and, to some extent, heterogenic target population in the present study did not reveal the difference between the 2 groups of pornography users and nonusers.

The results of the present study showed that the mean score of religiosity in women without a history of pornography use was slightly higher than the other group. However, this difference between the 2 groups was not significant. Perry and Schleifer's study also showed no significant association between different acts of religiosity (attending religious services and views on the Bible) and pornography use in women (29). However, other studies showed that people with a history of pornography use reported low religiosity, and non-religious people reported higher use (11, 21, 45). In the present study, all participants were Muslim, and the mean score of religiosity in women with a history of pornography use was 7.45/10. It seems that the level of religiosity might not predict the usage of pornography in our population. This finding could interpret with the unique context of Iran, rapid modernization, and extended popularity and accessibility of the internet and smartphones along with governmental interference in religious affairs and law restrictions for pornography use.

According to Bennett et al, the use of pornography by religious people is associated with feelings of guilt, and there is a possibility of harm resulting from this feeling of guilt in religious people (19). It should be studied how and how much these religious women might be harmed by pornography use in the Iranian context.

The present study showed that the mean score of sexual desire was statistically significantly higher in women with a history of pornography use than in women without a history of pornography use. Various studies showed that women's use of pornography is significantly associated with higher sexual desire (21, 43, 44). While the study of Bennett et al showed that pornography use was not significantly associated with the sexual desire of the partner (19). Ashton et al showed that pornography could both enhance and disrupt sexual pleasure (47). Recent studies have suggested that the expected effects of pornography may actually decrease as the pornography increases (15, 48). Nevertheless, it is not clear whether pornography use is more common in women with higher sexual desire or if increased sexual desire in women is a by-product of pornography use.

Marital satisfaction is a major and complex aspect of a marital relationship that does not arise spontaneously and requires the efforts of couples, which has a positive and significant relationship with sexual desire in couples (49, 50). The present study showed that the mean score of marital satisfaction was lower in women with a history of pornography use than in women without a history of pornography use, though this difference was not significant. Contrary to the results of the present study, Jafarzadeh Fadaki and Amani's study showed a negative and significant relationship between marital satisfaction and pornography use in students, and with increased marital satisfaction, pornography use decreased (30). Perry and Schleifer's study also showed that those who viewed more pornography reported lower levels of marital satisfaction than those who viewed pornography less or never (29). Decreased marital satisfaction may be associated with less sexual intimacy, leading women to use more pornography. On the contrary, we can conclude that pornography use may help women to gain some knowledge about their sexual needs, and if those needs are not answered by their partner, it might lead to less sexual connection and marital satisfaction.

The results of the present study showed that after controlling the effect of the variables of education level, job status, quality of couple relationship, type of marriage, habitation after marriage, and age, among the 9 components of marital satisfaction, only the mean score of the financial management component was significantly higher in the pornography use group compared with the nonuser group. Regarding the sub-components of conflict resolution, leisure activities, marriage and children, family and friends, and financial management, our results are consistent with Jafarzadeh Fadaki and Amani's study; however, regarding the other sub-components, it is inconsistent (30).

The present study provides valuable information about the prevalence of pornography use in the Iranian women population in Rafsanjan city. This target population is unique and trapped among rapid modernization and strong and rooted traditions and religious rules. These women are mostly educated and have extended access to the internet in a context with tight marital bounds enforced by religion and culture. These unique properties could explain the novelty of the results: Women’s pornography use without any predictors. We encountered a number of limitations in conducting this study. Of the 783 women invited, 284 participated in the study. This low response rate was absolutely expected regarding tight marital bounds, patriarchal context, and topic sensitivity in the context of Iran. Regarding validity, like other studies on sexuality, we were concerned about the accuracy of information entered in the questionnaires. We had a telephone conversation with the women and guaranteed confidentiality. Finally, social media was employed to complete the information instead of a paper questionnaire.

5.1. Conclusions

Health care professionals need to know the relationship between pornography use and women’s sexual features. The results of the present study showed that marital satisfaction was not related to women’s pornography use. After removing the effect of demographic variables, there is a positive and significant relationship between sexual desire and pornography. More studies are required to reveal the relationship between pornography use on the sexual features of women and their partners.