1. Background

Suicide is one of the most serious public health concerns worldwide (1-4). Globally, about 800 000 individuals die annually from suicide. In addition, there are more than 20 attempts per suicide (5). The individual shows suicidal behavior in the social environment when psychological pressures are beyond a person’s tolerance (6). Suicide is defined as suicidal thinking, concentrating, and planning for suicide (7). According to the Centers for Disease Control and the National Center for Health Statistics reports 2019, suicide is the second leading cause of death in individuals aged 15-24 years (2). Suicide is of great importance due to its negative consequences for families and economic costs for society (1).

Mental disorders (e.g., emotional ones), demographic variables (e.g., male gender and older age), socio-psychological variables (e.g., decreased hope and social isolation), and certain cultures and characteristics (e.g., self-criticism and perfectionism) are considered risk factors for suicidal ideation (8). Impulsivity as an unstable personality trait (9) is another risk factor that can potentially cause suicide attempts (2, 10). Impulsivity is defined as quick and unplanned actions to respond to internal or external stimuli, regardless of consequences for oneself or others (11), and categorized as an impulsive behavior or impulsive action and cognition impulsivity (12).

A review of the literature shows that impulsive individuals might be more at risk of suicide (2, 12, 13). The results of the study by McMahon et al. indicated that childhood impulsivity independently increases the risk of suicide and self-harm in adulthood (14). In a systematic review and meta-analysis, McHugh et al. showed that impulsive behaviors are positively correlated with self-harm and suicidal behaviors (15).

Researchers identified a number of protective factors psychologically supporting individuals, encouraging them to live, and therefore reducing the likelihood of suicide (15). The empirical evidence suggests that integrated self-knowledge, introduced as a kind of self-knowledge in positive psychology (11), might help reduce the tendency toward committing suicide and mental health problems (11), and research on it, as a component of mental health, promises the promotion of understanding psychological well-being among cultures (11).

Self-knowledge consists of two experiential and reflective aspects. The integration of experiential and reflective aspects of self constitutes integrative self-knowledge (16). In other words, integrative self-knowledge points to individuals’ striving to integrate their past, present, and future experiences for better adjustment and self-empowerment (12).

Some researchers believe that personal differences in self-knowledge are related to mental and physical well-being and can control and regulate behaviors, emotions, and understanding of personal problems and reduce anxiety and unpleasant thoughts (10). Valikhani et al. and Ghorbani et al. showed that individuals with limited self-knowledge are less flexible in controlling their thoughts and emotions, ignore their psychological and physical reactions to stressful events, and, as a result, cannot make the necessary modifications. In addition, individuals with high self-awareness tend to be self-integrative and combine negative and positive beliefs that automatically reduce cognitive distortions of the environment and create an accurate and fact-based imagination of self (17, 32). The study by Shariat et al. showed that individuals with integrative self-knowledge are optimistic and resilient in communication and interaction with others and have no depression and unreasonable self-criticism (18)

In addition, previous studies showed a positive relationship between self-knowledge and psychological protective factors, such as self-compassion, mindfulness, psychological well-being, self-esteem, constructive thinking, more consistent assessment of emotions (12), and a negative relationship between self-knowledge with anxiety and perceived stress (17), rumination, and suppression of emotions (13, 14, 19). Therefore, it is expected that the rate of self-criticism and other psychological damage associated with it, including suicide, decreases with the increase of integrative self-knowledge (19). In addition, the effect of integrative self-knowledge on adaptation and self-regulation and their role in the occurrence of behavior (including health-promoting ones) also raise attention to this psychological variable as a possible protective factor against suicide (20).

Since studies on suicide included different groups and employed various measurement methods (1), and due to a reducing the suicide rate by 10% in Iran (14), it is necessary to comprehend knowledge of risk factors as warning signs and protective factors for suicide to prevent suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts in Zahedan, Iran, which also has a special cultural, social, and religious context.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to determine the relationship between impulsivity and integrative self-knowledge and the tendency toward suicide among the adult population of Zahedan, Iran.

3. Materials and Methods

The present descriptive-correlational study was performed on 422 adults aged 20 years and older in Zahedan. The sample was estimated using Cochran's formula, and the error rate (d) was 5% of the sample size of 422 individuals (384 subjects, the number of samples according to Cochran's formula and 10% equivalent (38 people because the questionnaires may not be returned or not answered or Be distorted), selected by the cluster sampling method. This study was conducted based on census statistics, and 422 individuals aged 20 years and older were selected. Based on the five regions of Zahedan municipality, two neighborhoods were selected from each region, and by attending different neighborhoods of Zahedan city, about 40 individuals aged 20 years and above were selected from both male and female subjects. The questionnaires were administered to the study subjects. The inclusion criteria were having a high school education at the minimum, being between 20 and 50 years old, and signing the written consent form to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included a history of diagnosis of mental illness in the past two years and a history of substance abuse.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan Branch (ethics code: IR.IAU.ZAH.REC.1399.002).

A total of 422 individuals from 10 neighborhoods in Zahedan participated in the research by referring to the homes of individuals who were satisfied.

To observe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) prevention and control guidelines, the questionnaires were completed electronically, and those not interested in electronic ways were provided with face masks, gloves, and pens. The subjects were informed about voluntary participation in the research and their right to withdraw from the study at any stage. The data were collected using the Beck scale for suicidal ideation , Barrat impulsiveness (21) and integrative self-knowledge scales (Ghorbani et al., 2008) (22).

Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSSI) is a 19-item self-assessment tool. Using Cronbach's alpha method, the coefficients were 0.87 to 0.97, and using the test-retest method, the reliability of the test was 0.54. Additionally, the validity of the scale using Cronbach's alpha method is equal to 0.95.

Barat Impulsivity Scale can measure cognitive, motor, and unplanned impulsivity and is a self-report tool that examines the personality and behavioral components of impulsivity. Barratt obtained a reliability of about 0.81 for the total score (21). Ekhtiari et al. used this questionnaire in two groups of healthy individuals and consumers (23). In the group of healthy individuals, Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.48, 0.63, 0.79, and 0.83 for the subscale, respectively. They reported programmatic, motor, cognitive, and total scores.

The Cohesive Self-Knowledge Scale was developed by Ghorbani et al. in 2008. This scale has three subscales: Reflective self-knowledge, empirical self-knowledge, and cohesive self-knowledge (22). In JaliliRad's research, to verify the validity of the retest coefficient has been reported as 0.75 (P ≤ 0.001) (24). The reliability of this scale in a group of 230 students of the University of Tehran, Iran, was as follows:

Cronbach's alpha coefficient for experienced self-knowledge and reflective self-knowledge was 0.90 and 0.84, respectively. The correlation between the two aspects was equal to r = 0.74 (20).

Pearson correlation coefficient and regression analysis were utilized to analyze the data at the descriptive level (frequency and percentage), and Pearson correlation and regression analysis were used to examine the research question at the inferential level. Moreover, SPSS software (version 26) was used.

4. Results

According to the results shown in Table 1, the study participants were within the age range of 20 years and older, with a mean age of 29.40 ± 9.36 years. Due to dropouts, the final sample size decreased to 380. The majority of respondents belonged to the age group of 17-34 years. The majority of subjects (55.8%) were employed and had a middle socioeconomic level (47.6%).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | |

| 20 - 34 | 281 (66.9) |

| 35 - 52 | 108 (25.59) |

| 53 - 70 | 33 (07.51) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 254 (60.47) |

| Female | 166 (39.33) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 255 (61.8) |

| Married | 167 (38.2) |

| Level of education | |

| Below high school diploma | 50 (13.2) |

| High school diploma | 174 (45.8) |

| Associate degree | 62 (9.7) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 117 (26.3) |

| Master’s degree | 19 (4.5) |

| Occupational status | |

| Employed | 232 (54.97) |

| Jobless | 190 (45.03) |

| Socioeconomic class | |

| Upper | 132 (31.28) |

| Middle | 223 (52.85) |

| Lower | 67 (15.87) |

| Total | 420 (100) |

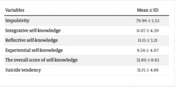

The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the study variables are shown in Table 2. According to the results shown in Table 2, reflective self-knowledge had the highest mean among the self-knowledge subscales. The overall mean was 79.96 ± 5.52 for impulsivity and 3.15 ± 4.88 for suicidal tendency.

| Variables | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Impulsivity | 79.96 ± 5.52 |

| Integrative self-knowledge | 11.07 ± 4.30 |

| Reflective self-knowledge | 11.15 ± 3.21 |

| Experiential self-knowledge | 9.56 ± 4.07 |

| The overall score of self-knowledge | 31.80 ± 8.83 |

| Suicide tendency | 31.15 ± 4.88 |

To investigate the relationship between variables and suicidal ideation, the results of the Pearson correlation coefficient showed that impulsivity (P ≤ 0.001, r = 0.18) had a direct and significant relationship with suicidal ideation at a 99% confidence interval. Furthermore, the dimensions of integrative self-knowledge, including reflective (P ≤ 0.001, r = -0.11), experiential (P ≤ 0.001, r = -0.29), integrative (P ≤ 0.001, r = -0.31), and the overall score of integrative self-knowledge (P ≤ 0.001, r = -0.25), had a significant and inverse relationship with suicidal ideation at 99% confidence interval (CI) (Table 3).

| Variables | Tendency to Suicide | |

|---|---|---|

| Sig | r | |

| Impulsivity | 0.18 | 0.001 |

| Reflective self-knowledge | -0.11 | 0.01 |

| Experiential self-knowledge | -0.29 | 0.001 |

| Integrative self-knowledge | -0.31 | 0.001 |

| The overall score of self-knowledge | -0.25 | 0.001 |

Table 4 shows the results of linear regression analysis to predict suicidal ideation based on impulsivity. The results of linear regression analysis showed that the impulsivity variable could explain 0.03% of the suicidal ideation variance. Therefore, impulsivity was a direct and significant predictor for suicidal tendency (P = 0.001, Beta = 0.18) (Table 4).

| Predictive Variable | Correlation | Correlation Coefficient | Adjusted R-Squared | β | t | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulsivity | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 3.56 | 12.69 | 0.001 |

Table 5 shows the prediction of suicidal ideation based on integrative self-knowledge and impulsivity. In predicting the tendency toward suicidal ideation based on integrative self-knowledge, the results of stepwise regression analysis showed that in the first step, the integrative self-knowledge was entered into the equation and could explain 0.09% of suicidal ideation variance, and in the second step, integrative self-knowledge entered the equation with impulsivity and could explain 11% of suicide tendency. Therefore, integrative self-knowledge (P = 0.001, β = 0.29) and impulsivity (P = 0.004, β = -0.10) had a significant and inverse relationship with suicidal ideation scores and were significant and inverse predictors of suicidal ideation (Table 5).

| Step | Predictive Variable | Correlation | Correlation Coefficient | Adjusted R-Squared | β | t | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Integrative self-knowledge | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.09 | -0.31 | -6.51 | 42.43 | 0.001 |

| 2nd | Integrative self-knowledge | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.10 | -0.29 | -5.74 | 23.37 | 0.001 |

| Impulsivity | 0.10 | -2.76 | 23.37 | 0.004 |

Table 6 shows the prediction of suicidal ideation based on reflective self-knowledge and impulsivity. In predicting the tendency toward suicidal ideation based on reflective self-knowledge, the results of regression analysis showed that in the very first step, the impulsivity variable could explain 0.03% of the suicidal ideation variance. Therefore, impulsivity was a direct and significant predictor for suicidal tendency (P = 0.001, Beta = 0.18). and reflective self-knowledge were removed from the regression equation and were not strong predictors for the regression equation (Table 6).

| Predictive Variable | Correlation | Correlation Coefficient | Adjusted R-Squared | β | t | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulsivity | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 3.56 | 12.69 | 0.001 |

Table 7 shows the prediction of suicidal ideation based on experiential self-knowledge and impulsivity. In predicting the tendency toward suicidal ideation based on experiential self-knowledge, the results of stepwise regression analysis showed that in the first step, the experiential self-knowledge was entered into the equation and could explain 0.08% of suicidal ideation variance, and in the second step, experiential self-knowledge and impulsivity could explain 0.09 % of suicide tendency. Therefore, experiential self-knowledge ( P = 0.001, β =- 0.29) and impulsivity (P = 0.002, β = -0.11) had a significant and inverse relationship with suicidal ideation scores and were a significant and inverse predictor of suicidal ideation and independent variables could explain changes in a dependent variable ( Table 7).

| Step | Predictive Variable | Correlation | Correlation Coefficient | Adjusted R-Squared | β | t | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Experiential self-knowledge | 0.29 | 0.08 | 0.08 | -0.29 | -6.007 | 36.07 | 0.001 |

| 2nd | Experiential self-knowledge | 0.31 | 0.09 | 0.09 | -0.26 | -5.28 | 20.74 | 0.001 |

| Impulsivity | -0.11 | -2.23 | 20.74 | 0.002 |

5. Discussion

Factors affecting suicide as a global phenomenon are diverse and complex (4). The present study, with the aim of expanding the understanding of these factors, showed that impulsivity had a positive and significant relationship with suicidal ideation and was its positive and significant predictor. Shelef et al. observed that individuals with high impulsivity have more tendency toward suicide, and the prevalence of suicide was significantly higher among them than individuals without impulsivity (25). Beckman et al. also reported that young individuals with more efforts to commit suicide and self-harm showed more impulsive behaviors (26). These findings are consistent with the present study results and those of Auerbach et al., Vargas-Medrano et al., Liu et al., Pereira et al. and Shelef, et al., in which the impulsive behavior was reported as a risk factor for suicide (2, 3, 10, 12, 25)

In explaining these findings, it can be said that impulsivity, as a behavioral structure, includes a wide range of behaviors that are often considered maladaptive behaviors with the following characteristics: Lower sensitivity to negative consequences, hastily behaviors, and unplanned thoughtless actions against stimuli, which can be a turning point in many social problems, psychological disorders, and low quality of life (4, 12, 15, 27). In addition, getting rid of negative outcomes and achieving short-term benefits over long-term ones leads to impulsive behavior; therefore, impulsivity (negative urgency) might increase vulnerability to inconsistent behaviors, such as self-harm and suicide (28). Although many studies indicated that suicide is an impulsive behavior, the meta-analysis by Guptaet and Pandey suggested another alternative in the perspective of the relationship between impulsivity and suicidal behavior (29) They believed that individuals with high impulsivity often commit suicide, attributed to their increased suicidal ideation. Suicide ideation is achieved through negative and painful experiences, higher in individuals with higher impulsivity (12). Hadzic et al. believed that experiencing these behaviors and related pain can reduce the fear of death and increase the risk of suicide. Likewise, impulsivity is a major predictor of involvement and experience of non-fatal self-harm (30).

Hadzic et al. emphasized that impulsivity, as a distant risk factor for suicidal ideation, leads to negative behaviors and is associated with the fluctuation of passive suicidal ideation (30). In the studies by Wang et al. and Ghorbani et al. et al. only in a moderating role and in combination with hopelessness and depression variables, impulsivity had a higher predictive power for suicidal thoughts (31, 32).

The present study findings showed that the dimensions and the overall score of integrative self-knowledge had an inverse and significant relationship with suicidal tendency, and integrative and experiential self-knowledge were the inverse and significant predictors of suicidal ideation. The inverse relationship between integrative self-knowledge and suicide attempts was also observed in other studies. The study by Christman examined the protective nature of some resilient psychological factors, including a sense of integration into Indian American and Native Alaskan adult populations, experiencing the highest suicide rates among all ethnic groups in the United States, and showed that integrative self-knowledge predicts helplessness and suicide (33). In a study by Drum et al. integrative self-knowledge had an inverse relationship with suicidal ideation and thoughts, and it was a good predictor for suicidal thoughts and ideation in students (34). A review study by Prasad Gupta and Pandey showed a significant and inverse relationship between integrative self-knowledge as a potential for adaptation to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (29).

In explaining these findings, it can be said that integrative self-knowledge indicates the individual’s view of life and capacity to respond to stressful events and is a way to understand the relationship with the world, which includes three main components of controllability (life is somewhat predictable and understandable), manageability (there are enough resources for personal desires), and meaningfulness (life is meaningful and logic and problems are worth the energy investment) (19, 28). Additionally, a part of the result of the present study showed that reflective self-knowledge alone did not predict suicidal tendencies. These findings, inconsistent with those of the previous information, reinforced the idea that self-knowledge is a complex and multifactorial concept consisting of various personality and behavioral aspects (12).

This finding can be due to the fact that in self-knowledge, a person analyzes his/her experiences through advanced and complex cognitive actions and achieves more complex mental plans that facilitate her adaptation.

Self-knowledge provides immediate input from individual experiences, which is necessary to face challenges and achieve goals and prevents uncontrolled responses. On the other hand, reflective self-knowledge is the cognitive processing of information related to the past. These two types of self-knowledge are closely related (27).

In the face of difficult and challenging situations that require attention to oneself, in the present, among the dimensions of self-knowledge, experiential self-knowledge is more important. In this situation, relying on reflective self-knowledge can lead to a habitual response in which the person has little connection with reality. Therefore, it is less important (35).

Despite the clinical significance of the findings, this study is limited to the self-reported response of individuals; therefore, caution should be exercised in generalizing its results (36). Other limitations of the present study include the use of questionnaires to collect information and the fact that methods such as interviews were not used in data collection. It is suggested that educational workshops be implemented to strengthen and improve self-knowledge and emotional regulation strategies. Additionally, multivariate comparative studies on a normal population and clinical examples are suggested to further differentiate each relationship and implement other risk factors to identify moderating factors and assess suicidal ideation as passive and active thoughts (including on-purpose or planning).

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of the present study are consistent with the theory that impulsivity and integrative self-knowledge are associated with suicidal ideation. Since suicide is potentially preventable (3), a complete understanding of the relationship between protective and risk factors, as a potential way to identify high-risk individuals, can lead to making practical policies for prevention and intervention at both individual and population levels.