1. Background

Improving health interventions, especially for adolescents and young adults, who constitute the largest share of the population in many developing countries, has become a topic of interest for policymakers and health managers. In this regard, in addition to paying attention to the content of the health program, based on the health priorities, required improvement and reforms should be followed seriously (1, 2).

The increasing trends of youth health threats; in four general domains of drug abuse, suicide, high-risk sexual behaviors, and aggression, have become the most important priorities of both individual and public health (3, 4). The efforts of policymakers and health managers are focused on as much as possible controlling and reducing suicide trends (5, 6). Reviewing the relevant scientific evidence revealing the existing gaps by analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of the programs provides the possibility of optimal design of intervention programs and development of a roadmap for the promotion of spiritual health (1, 2).

Resulting from the review of the literature, the most important research concept in this field is the association between spirituality and youth tendency that can improve the effectiveness of intervention programs. Another important gap is the need to pay attention to the national or even local characteristics of each population, which is considered in the present study (2, 7).

Studies confirmed that the social burden of suicide is one of the most important health and social challenges that most countries are dealing with (2-4). Meanwhile, suicide is known as a major public health problem worldwide and is a major concern and problem for psychiatrists, psychologists, and other professionals who are somehow involved with the psychological health issues of young people (2, 4). This phenomenon is also considered the third major cause of death among young people (3, 4). Many factors can increase the risk of suicide among young people (4). Low quality of life and the spiritual aspect of health, especially among young people, are among the factors that can increase the risk of suicide (8). The association between well-being and suicidal tendencies has been proven among college students as an important factor (5, 7).

Despite the importance and priority of the problem, studies on the promotion and expansion of spiritual interventions in the prevention and control of suicide are scattered and limited to some sub-population groups. Most researchers confirm the simultaneous approaches to different aspects of health in improving suicidal attitudes and behavior (3, 4).

As the main considerable point, concerns of spiritual health and related interventions in societies like Iran are mostly integrated with religious values and beliefs. Due to the complexity of the nature of the problem, addressing the current situation and planning for effective and acceptable interventions are the most important concepts (9, 10).

2. Objectives

The present paper aims to provide practical suggestions for developing and promoting a national program. The aim of the applied research is to promote and expand spiritual interventions in the prevention and management of suicide by sharing the results of the study with stakeholders in the policy-making, managerial, and executive fields.

3. Materials and Methods

This is a three-phase project study, in each stage, using the results of the previous section helps to complete the information and general conclusions of the project. The implementation of this research consisted of three stages as follows:

(1) First phase: Systematic review of spiritual health interventions in the prevention and management of suicide in Iran University Students.

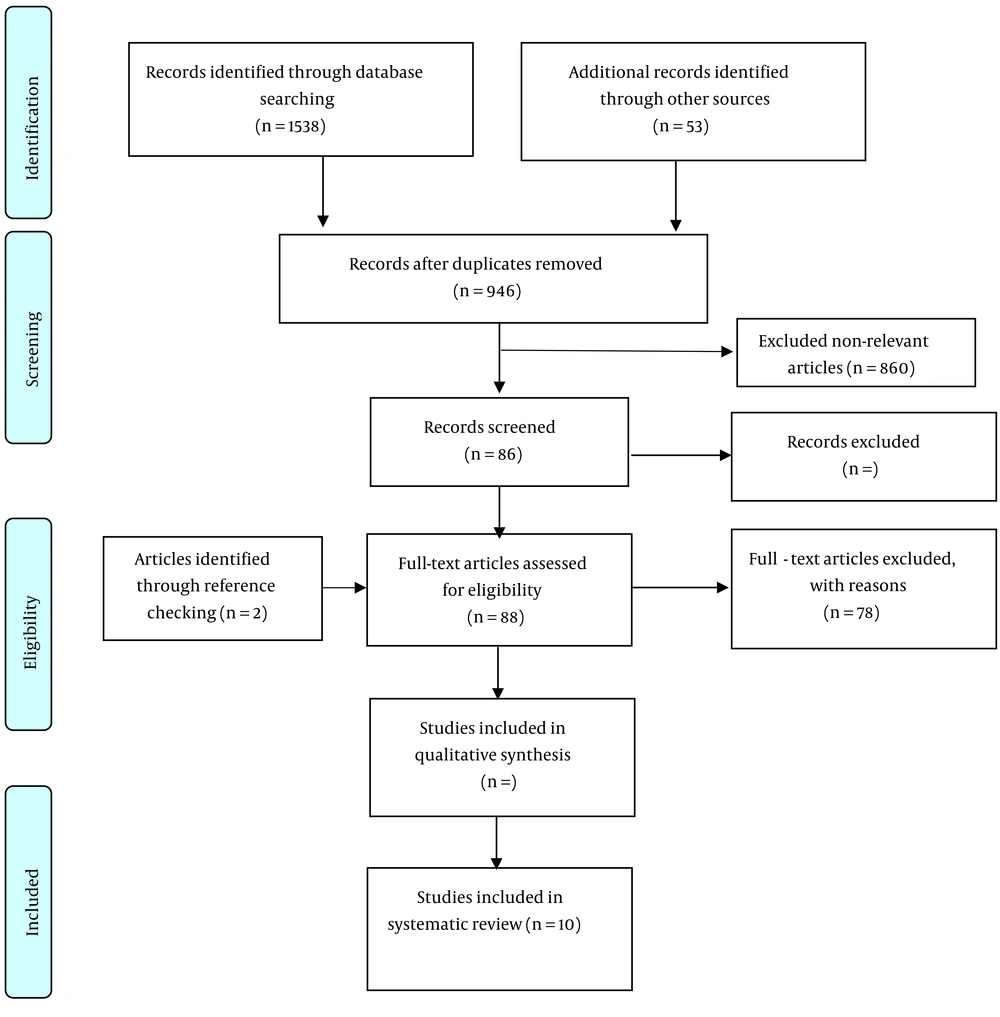

The systematic review was conducted based on the guidelines of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (11). Figure 1 shows the process of searching and refining the text regardless of the time and language of the papers, all eligible studies were included in the study. In this regard, the goal was to access studies that have somehow investigated spiritual interventions in the high-risk behaviors of university students in Iran. For this purpose, all observational and analytical studies were included. In papers with repeated citations, duplicates were removed.

3.1. Search Strategy

In order to develop a search strategy based on the English and Persian equivalent of keywords, a search framework was set up under the supervision of technical experts. Using the terms MeSH term, Emtree, and suitable keywords, without considering the restrictions on the date of conducting studies or publishing papers and without considering language restrictions, the search was performed through the main international databases of PubMed, ISI/WOS, and Scopus. PsycINFO and CINAHL data banks were also searched. In the continuation of the search, it was completed by checking the internal databases of Iran.doc, SID, and the Barekat system. In addition to electronic sources, relevant national and international congresses were also searched. The main roots of developing a search strategy based on keywords and phrases in the field of “spiritual interventions,” “health interventions,” “health programs,” “adolescents,” “young people,” “students,” and “suicide” were searched.

3.2. Study Selection

Following the running of search procedures, for better data management, the results were transferred to the EndNote software, and after reviewing and removing duplicates, the remaining findings were refined in three stages for the relevancy of titles, abstracts, and full texts.

3.3. Quality Assessment

The quality of the included papers was assessed using the STROBE checklists. The number of the 22 STROBE items was divided into three categories: (1) high quality (scored 15 - 22); (2) moderate quality (scored 8 - 15); and (3) low quality (scored 0 - 7). Disagreements were resolved through group discussion (12).

3.4. Data Extraction

After quality assessment of the remaining related papers, using a customized form, the following data were extracted: First author, year of publication, country, research design, source of the types of study population, sample size, the patient’s demographic data, and the interventions and outcomes.

3.5. Data Analysis

Data extracted and aggregated for predefined aims. According to the nature of the data, qualitative statistics were used to describe the data and for the analysis, the coding method of the study findings was used according to the type of effective factor, type of interventions, results, and consequences.

(2) Second phase: Explanation of strengths, weaknesses, challenges, and suggestions for improving interventions from the point of view of the key informants.

3.6. Study Design and Participants

In this phase of the project, using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ), a qualitative study was run (13). To address the factors affecting the consequence of spiritual interventions for the prevention of youth suicide, using the snowball method, following the determination of the initial list of key informants and stakeholders, 15 in-depth interviews were conducted based on the set goals. The sampling continued until no new categories, themes, or explanations emerged (data saturation).

3.7. Guide-Questioning

The interview guide-questioning was designed based on relevant literature and study objectives. The reliability and validity of the tools, as the value of trust and accuracy, were confirmed through a pilot study using semi-structured interviews with 2 participants.

3.8. Interviews

Data were collected through deep, semi-structured, face-to-face interviews. At the beginning of the sessions, research goals and methods were explained to the participants. Each session lasted about 45 minutes. Interviews were planned in a peaceful environment, preferably at the workplace of participants. The beginning of questions was open-ended ones based on the study objectives. The interview continued with exploratory questions and continued in each session until reaching the saturation limit in data collection, meaning that no new data will be provided by the interviewees as the sessions continue.

3.9. Data Analysis

After completing the data collection stage, the data were analyzed based on the conventional content analysis method through 4 steps: (1) transcription of the interviews, (2) deep reading of the text to understand its general content, (3) extracting the units of meaning and initial codes, and (4) classification of codes into more comprehensive categories. The findings were used along with other results of the previous stage to provide practical points (14).

(3) Third phase: Propose suitable suggestions for national spiritual interventions in suicide prevention and management: In this subsequent stage, after aggregating the results obtained from the review of related texts, studies, and documents and the points of view of key informants, a comprehensive panel of experts led to proposing practical suggestions for improving the running program or developing practical interventions (15). A session of interviews was set with 16 related key informants with dialogue and sharing conceptual insights. Discussions continued on each of the findings until reaching a consensus. The final results were determined based on the approval of the group.

3.10. Ethical Consideration

In the first phase, to access the full texts of the papers that were not available through electronic databases and to complete the required information, emails were sent to the corresponding authors. In the second and third parts of the study, the participants were informed about confidentiality, and their participation was voluntary, and they were informed about their right to withdraw from the study at any time or even during the interviews.

4. Results

In this section, the findings of the study are presented based on the steps performed in three corresponding sections.

4.1. Systematic Review

4.1.1. Study Characteristics

Based on the results of the searches, the time period of relevant studies was from 1957 to 2020 (Figure 1). Through the first stage, 1538 studies were obtained from international sources and 53 studies were from internal data banks. After removing duplicates, 946 papers entered to refining process, after three steps of refining based on the titles, abstracts and full texts, data extracted from 12 remained eligible papers (Table 1).

| No. | Citation | Data Gathering Tools | The Most Important Findings of the Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Habibi et al. (16) | Checklist created by the researcher in order to investigate the dimensions of cognitive prevalence, depression disorder and suicidal behaviors in the student | Depression (10 to 85%) and suicide (suicidal thoughts from 2.6 to 7.42% and suicide attempt rate from 5.3 to 8.1%) were among the most common mental health problems of students. |

| 2 | Hajialiani et al. (17) | Beck (1979) Suicidal thoughts questionnaire and Neff and et al. self-compassion scale (SCS) (2009). | Cognitive therapy based on mindfulness is an effective way to prevent student suicide. |

| 3 | Laghaei et al. (18) | Beck Suicidal Ideation Scale (BSI), Conner and Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RIS), Coping with Stressful Conditions Questionnaire and Beck Depression Questionnaire (BDI-13) | Resilience, problem-oriented and emotion-oriented coping strategies, and depression are among the major influencing factors on suicidal ideation. |

| 4 | Matinpour and et al. (19) | Hill's Perfectionism Questionnaires, PANAS positive and negative affect, Madzly's Obsessive-Compulsive Questionnaire and Beck's suicidal thought (BSSI) | A positive and significant relationship was obtained between perfectionism and suicidal thoughts. |

| 5 | Heshmati et al. (20) | Toronto Alexithymi (TAS)-20 Questionnaires, responsibility attitude, positive and negative affect, Yale-Brown obsessive-compulsive and Beck suicidal thoughts | Suicidal thoughts are stronger in students with obsessive tendencies. |

| 6 | Takalvi and Ghodrati (21) | Beck Suicidal Thoughts Questionnaire, Simpson Attachment Styles Questionnaire (AAI) and Rosse Love Trauma Questionnaire | Attachment styles and severity of emotional failure are predictors for the probability of students' suicidal thoughts. |

| 7 | Hashemi (22) | Depression Questionnaire, Beck suicidal thoughts, worry and rumination | Metacognitive therapy could decrease the risk of suicide attempts. |

| 8 | Masoumi and Ebrahimi (23) | Descriptive research | The components (Repression of thoughts, replacement of thoughts, and transformation of imagination into thoughts) of cognitive avoidance and emotional cognitive regulation can significantly predict suicidal thoughts. |

| 9 | Akbari et al. (24) | Family Assessment Instrument Questionnaire (FAD), Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) and Beck Suicidal thoughts Scale (BSS) | The association between the perception of the overall functioning of the family and suicidal was significant in low levels of despair. |

| 10 | Ebrahimi et al. (25) | Questionnaires of suicidal thoughts, Young's maladaptive schemas, Glasser's search for meaning and basic needs | There was a significant association between the severity of basic needs and suicide tendencies in students. |

| 11 | Ghadampour et al. (26) | Questionnaires of demographic information, psychological vulnerability, suicidal thoughts and cyber harassment | cyber harassment can be an interpersonal risk factor to increasing the suicidal thoughts. |

| 12 | Golchin et al. (27) | Qualitative group discussion guide | The categories of failure, laziness and aimlessness, forced marriages, psychological pressures, the university being “causal conditions”, economic, social pressures and family breaks as “background conditions”. |

The Main Key Points of Suicide Attempts in Iranian Students

4.1.2. Analytical Results

Based on published documents; factors related to suicide of teenagers and young people could be classified in three main categories of; demographic factors (age, gender, sexual orientation, race and ethnicity), environmental factors (lack of family or social support, history of arrest or imprisonment, poor life skills, family history of suicide, internet and social media) and psychological (mental disorders, adverse life events and history of childhood abuse, academic stress, drug and alcohol use, cyberbullying). The finding provide that people who with one or more risk factors are more likely to engage in suicidal behaviors.

Associated factors were psychiatric history or psychiatric problems, female sex, positive history of suicidal behaviour, family history of suicide, and drug dependency.

4.1.3. The Qualitative Study

4.1.3.1. Interviews and Participants

Fifteen in-depth interviews were conducted with related expert from different diciplinc. Nine participants were male and the mean age was 44.4 ± 0.41 years and their education varied from master’s degree to Ph.D. subspecialty. All the participants resided in Tehran.

4.1.3.2. Qualitative Results

Based on the analysis of the results of the qualitative phase of the study, five themes and twenty-six subthemes were extracted as follows (Table 2).

| Theme and Sub Theme | Main Code |

|---|---|

| Identify existing programs | |

| Program content | -Principles of counseling |

| -The difference between guidance and advice | |

| -Mental health | |

| -Common physical and mental problems of students | |

| -Mental health | |

| -Risky behaviors | |

| -Prevention of social damage | |

| Objectives of the program | -Promotion of spiritual health |

| -Improving social performance | |

| -Prevention of social damage | |

| Educational needs | -Factors affecting life satisfaction |

| -Common mental problems | |

| -Risk factors and their prevention | |

| -Psychological characteristics of the opposite sex | |

| -Correcting false beliefs | |

| -Commitment and responsibility in the spiritual field | |

| -Information about methods of accessing services | |

| -Correcting healthy behaviors from unhealthy ones | |

| -Effective communication skills and healthy interpersonal communication | |

| -Methods of preventing the monotony of life | |

| -Ability and focus on goals | |

| -Functional frameworks of theoretical concepts | |

| Target groups | -Students of different academic levels |

| Trustee organization | -Ministry of Health |

| -Assistant of Health, Office of Mental Health | |

| Strengths of the program | |

| Content | - |

| Continuity | - |

| Interdepartmental cooperation | - |

| Obstacles and challenges of program implementation | |

| Levels of decision makers | - Change of managers and their points of view |

| Service providers users of the service | -Time |

| -Content: Lack of appropriateness of education with target group; existence of heterogeneity in the provision of training; failure to use appropriate training methods | |

| -Location | |

| -Cost | |

| Suggestions for improving the program | -Correction of incorrect information |

| Compliance with the basic | -Maintaining the basic conditions of consulting and observing secrecy and confidentiality |

| Principles of counseling | -Considering enough time to do the training |

| Adaptation of training to the main | -Education tailored to students' conditions (culture, education, etc.) |

| -Providing face-to-face training both individually and in groups | |

| Audience | -Considering the cultural distance between the new generation and the previous generations |

| Training needs assessment | -Empowerment is the main goal of education. |

| The role of the media | -Considering the real needs of the learner |

| -The use of radio and television in preparing attractive educational programs | |

| Early education | -Starting spiritual health education from schools |

| Using technology in education | -Using appropriate educational technologies in providing consultations |

| Content update | -Designing a spiritual health education system and providing virtual education |

| Interdepartmental cooperation | -Using standard tools to evaluate existing programs |

| The role of insurance | -Updating educational content according to the needs of the new generation |

| Process ownership | -Development of public and private centers in providing education |

| -Cooperation and participation of different disciplines in providing training and preventing risky behaviors | |

| -Insurance support for spiritual health services | |

| -Providing the necessity of health education at an acceptable cost | |

| -Decision makers' sense of ownership over the process | |

| Lessons learned | |

| Undesirability of compulsory education | -It is preferable to provide individual training over group training. |

| -Importance of needs assessment of spiritual health education | |

| -The need to monitor the education process |

Main Themes, Sub Themes and Main Codes of Qualitative Study

After analyzing the interviews and necessary coding, the categories of aimlessness, fear of the future, inappropriate field of study, failure, laziness and aimlessness, forced marriages, and psychological pressures were identified as “causal conditions”; economic and social pressures and family breaks as “background conditions”; and generational gap, religious break, gender inequality, and the need for attention as “intervening factors” were extracted as the main findings.

In the category of causal conditions, all participants during the interviews emphasized descriptions of their professional experiences, their opinions, and their suggestions that led to decreasing the effects of at-risk failures, students' laziness, and psychological pressures, as well as any other factor that, through psychological pressure, removes at-risk persons from a stable situation where they can make correct decisions based on real conditions.

One of the experts in the field of mental health emphasized that “one of the main requirements for suicide prevention is the diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders, especially in people who have a history of suicide attempts.”

Family conditions and the social and cultural context in which a person was born and raised, such as childhood experiences, economic well-being, and educational and communication patterns, were discussed as a complex and interconnected whole.

4.2. Expert Panel

Following the analysis and aggregation of the results of the systematic review and qualitative study, benefiting from the participation of experts from related disciplines, an expert panel was held to draw final conclusions and extract the practical findings. The empowerment of students regarding the concepts of spiritual health was one of the main strategies that all experts emphasized to prevent suicide. The need for the diagnosis of diseases such as depression, identification of risk factors such as high stress, aimlessness and confusion, fear of the future, inappropriate field of study, previous repeated failures, forced or failed marriages, and economic and social pressures were also among the factors that were the result of aggregation. Cumulative points of view were confirmed as factors related to suicide.

5. Discussion

This is a comprehensive multi-stage study on different dimensions of suicide prevention focused on students. Benefitting from a systematic approach, all available data from the systematic review were analyzed along with the findings of the qualitative study and consolidated and finalized by the panel of experts. Young people with psychotic disorders are at high risk of suicidal behavior, and many factors can affect this situation. In line with the results of the present study, other studies also confirm that early diagnosis of young people with psychosis is critical, as early intervention has been shown to prevent suicidal acts in young people (5, 28).

Based on the paradigm of qualitative studies, although the findings of the present investigation cannot be generalized to all societies and cultures, the results of the first phase of the study emphasize the prompt need for training and serious interventions on the spiritual health of young people, similar to many other regions of the world. It seems that these groups have more or less similar educational needs in different parts of Iran. Based on the results, we provide suggestions for practical spiritual interventions to manage, reduce, and prevent suicide among students, in accordance with the needs and values of the country (29, 30).

As suicide is a multifactorial problem related to different aspects of health, identifying the relationship between these factors could be helpful in designing and implementing preventive interventions (1, 19, 27). In line with the results of the present study, findings from similar research revealed that one of the first intervention priorities is the broad empowerment of at-risk groups. Among the thematic axes of empowerment programs, paying attention to spiritual health interventions significantly increases the probability of success and effectiveness of the programs. More than emphasizing needs assessment, evidence provides that religious approaches and behaviors and life skills are important recommendations (17, 30).

According to the opinions of many participants in the study, Iran is currently facing a significant challenge between tradition and modernity, which is rooted in individual and social changes in spiritual priorities. This issue, in other studies, highlights the necessity to pay attention to the transfer and influence of Western culture and ideas to the country, changing values, behavioral patterns, conflicting values between generations, and creating different attitudes toward issues, including those related to spiritual health. Naturally, in addition to lifestyle, these factors are also effective on high-risk behaviors such as suicide attempts in young people and students (3, 8, 14).

The findings of other research also consider the harms caused by cyberspace as emerging social harms and one of the main health-threatening factors, which require comprehensive training. Table 1 shows all the studies that have investigated the key points of suicide attempts among Iranian students.

In confirmation of the findings of the present study, the lack of priority in policy making is one of the challenges of providing spiritual health services, which has been mentioned by other studies. The lack of sufficient support from planners and officials is one of the causes of challenges in providing appropriate prevention and intervention services to students. Based on the results of the studies, intervention programs like any other program need the support of the authorities. Therefore, policy makers and health planners must be convinced to support the program practically.

Cultural resistance is one of other challenge in providing spritual health services. From this point of view findings of present study are along with the other studies (27-29). This is provided that cultural resistance to religious prohibitions is a bigger challenge in providing health educations.

The lack of formal training and empowerment considered as one of the most important reasons mentioned by most of the participant. Related to the scientific sources, deside of priority and importance of problem, Iran still does not have comprehensive and formal related population based plans. For this reason, the existence of unreliable sources causes the transmission of false beliefs and false information.

One of the strengths of the present study is to pay attention to one of the most important health priorities. Also, collecting and using all relevant data based on a systematic method is one of the important achievements of this paper. At the same time, based on the nature of secondary studies, due to the use of data provided in primary studies, the accuracy of reports depends on the accuracy and precision of primary data.

The suggestions for complementary future studies are as follows: Explaining the role of variety of sectors, including mental health professionals, social justice administrators, psychologists, spiritual leaders and faith healers in community based programs.

Defining the traning needs of spiritual health of students in accordance with their specific fields; determining the role of health workers in providing the spiritual health services; assesing the role of the mass media in promoting the spiritual health in different target groups.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, empowering of students regarding the deep concepts of spiritual health plays an important role in preventing of suicide. The categories of aimlessness, fear of the future, inappropriate field of study, failure, laziness and aimlessness, forced marriages, psychological pressures, economic and social pressures as important predisposing factors should be adress in prevention and management of student suicide.