1. Background

The spread of child sexual abuse material (CSAM) has become a significant problem in the 21st century. Despite increased public awareness and the efforts of governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), alarming statistics on CSAM persist. Online sexual solicitation (OSS) of children occurs when an adult stranger uses the Internet to access, interact with, and establish relationships with children, aiming to engage them in sexual conversations or actions, either online or offline. Online sexual solicitation can involve a variety of sexually explicit acts, whether desired or undesired by the child, such as initiating sexual conversations (e.g., cybersex, describing sexual acts, and exchanging sexual information), sharing pornographic images, arranging offline meetings, and engaging in sexual acts (1). Westlake has suggested that online sexual abuse encompasses images, videos, and texts depicting babies, children, and young people in sexual situations, as well as material portraying severe sexual assault.

The Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), a UK-based NGO, identified more than 153000 new web pages containing child sexual abuse images in 2020, marking a 16% increase compared to 2019 (2). Additionally, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has been a significant factor in the rising rates of online sexual abuse of children. The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) reported in 2021 that the pandemic had led to a 106% increase in online sexual abuse cases reported to the police in March 2021 compared to the same month the previous year. In Germany, national administrative data revealed that in 2016 there were 5687 cases of online distribution, purchase, possession, and production of sexually abusive content. By 2021, this figure had increased six-fold, reaching 39171 cases (3).

Moreover, there is a prevailing assumption that online abuse is a less severe form of child sexual abuse, which contributes to a limited understanding of its seriousness among professionals. This underestimation often results in a lack of urgency in addressing online abuse (4). Victims of online sexual abuse frequently report receiving less support from caregivers and limited legal protection. In some cases, victims are blamed for their experiences, and offenders receive more lenient sentences from the judicial system (4).

Numerous surveys and meta-analyses examining sexually abused individuals using various methods and samples have concluded that victims experience a wide range of medical, psychological, and behavioral disorders (5). These include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sexual dysfunction, high-risk sexual behaviors, suicidal tendencies, re-victimization, substance misuse, fear, anxiety, poor self-esteem, and interpersonal difficulties (5). However, the impact of sexual abuse varies among victims, influenced by factors such as the nature of the abuse, the victim’s perception of the abuse, past life experiences, and the level of support provided after the abuse. These factors can significantly affect the victim's reaction and the long-term impact of the abuse (6). Ventus et al. (7) suggested that some children exposed to sexual abuse might not exhibit any psychological reaction.

In addition to the above cases, conducting this research is important and necessary because the topic of online sexual abuse has not received much attention in contemporary Iranian society. On one hand, social norms are often influenced by culture, and on the other hand, the increasing prevalence of online sexual activities highlights the need to recognize and identify various social norms related to online sexual abuse among children and youth. This issue is particularly urgent given its growing significance.

Overall, it can be argued that children who experience sexual abuse may suffer from a wide range of consequences and injuries. However, none of the symptoms observed are exclusive to victims of sexual abuse. As a result, child sexual abuse should be considered a general, non-specific risk factor for psychopathology. Research has not yet clarified whether the same applies to victims of online sexual abuse. Given the significant national and international consequences of online child abuse, it is imperative to conduct more extensive studies on this phenomenon, focusing specifically on prevention strategies.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to analyze the experiences, underlying factors, consequences, and preventive strategies of online sexual abuse from the perspective of subject-matter experts.

3. Materials and Methods

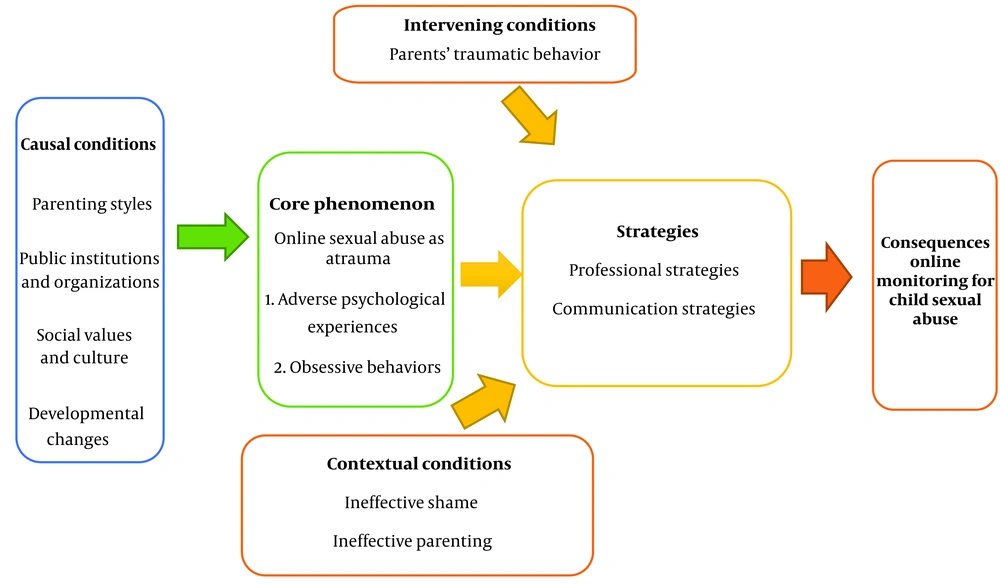

This qualitative study employed a grounded theory approach to investigate experts' experiences regarding online child sexual abuse (Figure 1) (8).

Participants were selected from among specialists in the field of sexual education in 2023. A total of 15 experts were chosen through purposive sampling until theoretical saturation was reached. Eligibility criteria included holding at least a master’s degree, possessing expertise in sexual education, and having experience working with children and adolescents who have been sexually abused. Data were collected through in-depth, semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions such as:

- “What is the scope of online child sexual abuse?”

- “What are the most important consequences of online child sexual abuse?”

- “What are the most important strategies to prevent online child sexual abuse?”

Before each interview, participants were briefed on the study’s objectives, and interviews were recorded with their consent. Each interview lasted between 45 and 60 minutes, with a total interview time of 1,051 minutes. The interviews were conducted from April 2023 to November 2023 over an 11-month period. All interviews were conducted in person and face-to-face at the Omid Counseling Center, affiliated with the education sector in Birjand, the capital of South Khorasan province.

The content of the interviews was transcribed into text files for subsequent analysis. The data were analyzed using Corbin and Strauss’s grounded theory approach (8). Underlying themes related to the phenomenon were extracted from the participants’ statements and categorized through open, axial, and selective coding. Open coding (conceptualization) was performed based on the research variables, interview questions, and participants' responses. To refine and group the obtained categories (grouping sentences with similar meanings), axial coding was applied. Finally, selective coding, which involves integrating categories and their relationships, was conducted to create a paradigm model.

The rigor of the data analysis was established in three steps. First, the interview transcripts were reviewed and confirmed by the participants (member checking). Second, the extracted themes were assessed and validated by comparing them with the raw interview data. Third, the interview content was coded by subject-matter experts (peer checking), achieving an inter-rater agreement of over 85%. The findings were further reviewed and validated by a panel of experts, who assessed the face validity of the proposed model in terms of relevance, coherence, and clarity of the statements. Finally, the extracted themes and categories were reviewed and revised by an expert in the fields of sexual education and sexology. The study protocol was approved under the code of ethics IR.IAU.TNB.REC.1402.036.

4. Results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants (experts) in this study. As can be seen, out of 15 participants, 7 (46.7%) were female and 8 (53.3%) were male. In addition, most of the participants (66.66%) held a Ph.D. degree, 3 participants (25%) had a master’s degree, and 1 participant (8.4%) was board-certified. Moreover, 4 participants were in the age group of 40 to 45 years, 3 were in the age group of 30 to 35 years, 4 were in the age group of 35 to 40 years, and 4 participants were in the age group of 50 to 55 years. Additionally, all the participants in this study were married.

| Row | Gender | Education | Age (y) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | Board-certified in child and adolescent psychiatry | 45 |

| 2 | Male | Ph.D. in clinical psychology | 42 |

| 3 | Female | MA in counseling | 39 |

| 4 | Female | MA in clinical psychology | 47 |

| 5 | Female | Ph.D. in counseling | 49 |

| 6 | Male | Ph.D. in educational psychology | 52 |

| 7 | Female | Ph.D. in counseling | 41 |

| 8 | Male | Ph.D. in sociology | 53 |

| 9 | Male | MSc. in software | 37 |

| 10 | Female | Ph.D. in educational psychology | 38 |

| 11 | Male | Ph.D. in educational sciences | 42 |

| 12 | Male | Ph.D. in counseling | 51 |

| 13 | Female | MA in clinical psychology | 38 |

| 14 | Male | Ph.D. in counseling | 42 |

| 15 | Male | Ph.D. in psychology | 51 |

The analysis of the data revealed four main categories (causal factors, intervening factors, underlying factors, consequences, and preventive strategies), 10 axial codes, and 41 open codes, as displayed in Table 2.

| Open Codes | Axial Codes | Selective Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Asking for photos and videos | Exposure to unsafe contact | Easy access to high-risk cyberspace |

| Sex chatting | ||

| Sex through video calls | ||

| Displaying children's photos by parents | ||

| Contacting with a fake profile | ||

| Non-updated textbooks | Unsupervised content production | Failure to understand the potential risks of cyberspace |

| Free access to VPNs | ||

| Ads on websites and channels | ||

| Free access to pornographic content | ||

| Online courses | Parents’ involvement with their personal concerns | |

| Parents' preoccupation with financial issues | ||

| Parents’ excessive use of social networks | ||

| Family shame about expressing sexual issues | Hidden shame and fear of expressing sexual issues | Immaturity in social interactions |

| Concealment of sexual abuse | ||

| The taboo of sexual issues in the community | ||

| The refusal of the educational system to teach sexual issues | ||

| Family conflicts | Ineffective parent/child interactions | |

| Parenting styles | ||

| Early exposure to cyberspace | ||

| Physical punishment | ||

| Occurrence of sexual disorders | Paving the way for the occurrence of psycho-social harms | Harms of unsupervised cyberspace |

| Occurrence of anxiety, depression, and worry | ||

| Academic failure | ||

| Damage to self-esteem | ||

| Suicide | ||

| Seeking approval from virtual people | Early sexual awakening | |

| Satisfying sexual curiosity | ||

| Masturbation | ||

| Sexual education | Raising parental awareness | Awareness and clarification as the keys to finding preventive support |

| Teaching physiological changes | ||

| Education through games and demonstrations | ||

| Teaching the psychological mechanisms of puberty | ||

| Responding to sexual curiosities | ||

| Interacting and talking with children | Educating parents | |

| Child supervision | ||

| Physical and emotional support from parents | ||

| Establishing a good relationship with children | ||

| Setting restrictions and rules in the family | ||

| Supervision by the school counselor | Seeking professional counseling support | |

| Referral to psychotherapy and counseling centers | ||

| Holding sex education workshops in kindergartens and schools |

4.1. Easy Access to Dangerous Cyberspace

4.1.1. Exposure to Unsafe Contacts

Sending sexual images: “I had a client who lived in the northern part of the country, and someone had asked her to send private photos and even videos on Instagram, to which she agreed” (Participant #1).

Communication with children and adolescents using fake profiles and identities: “I had a client who was in a relationship with a boy who pretended to be a girl by posting a girl’s profile. After sending voicemails in a girl’s voice, he was able to deceive the boy and asked him to send photos of his private parts” (Participant #15).

Sex chatting: “After a long time, I checked my daughter’s phone and saw that she had exchanged many messages with her friend, which I was ashamed to read, and all of them were about sexual issues” (Participant #3).

Sex through video calls: “I had a client who had met a boy in cyberspace, and he had asked the girl to send him sexual pictures of herself; otherwise, he would end the relationship. She sent him the photos because of her dependence, and the relationship continued to the extent that he asked the girl to perform some sexual acts online” (Participant #11).

Display of children's photos by parents: “Sometimes we create a separate page for our child on social platforms and post their photos and good behavior on that page, using the child’s language. There are also bloggers who share their own childhood photos on social platforms, and these bloggers are called ‘half-online children’” (Participant #3).

4.2. Failure to Understand the Potential Risks of Cyberspace

4.2.1. Unsupervised Content Production

Worldwide, schools and textbooks are among the richest and most reliable sources of transferring knowledge to students. However, in our country, nobody pays attention to these issues” (Participant #13).

- Free access to VPNs: “I just remembered that after the Iranian government filtered some social and online media, people began using VPNs more frequently. Unfortunately, this has made it easier for children to access websites with sexually explicit and pornographic content” (Participant #1).

- Free access to various networks and websites, including pornographic sites: “Yes, we’ve had many cases, especially on Instagram and even Rubika. Unfortunately, there are channels and pages that publish immoral content, making it accessible to uninformed teenagers and children” (Participant #6).

4.2.2. Parents’ Involvement with Their Personal Concerns

- COVID-19 and online education: “During the COVID-19 pandemic, children attended online courses through educational platforms. This gave them access to numerous websites with sexually explicit content, and their parents were unaware of what was happening” (Participant #7).

- Parents' preoccupation with financial issues: “Many parents are preoccupied with financial issues and often work two shifts due to high inflation and the dire economic situation in Iran. These parents lack the time and energy to focus on their children, leaving them to spend their time on mobile phones” (Participant #6).

4.3. Immaturity in Social Interactions

4.3.1. Hidden Shame and Fear of Expressing Sexual Issues

“Due to feelings of shame and modesty, many parents in Iran avoid discussing sexual issues with their children. Additionally, there is no sex education provided within Iranian families” (Participant #9).

- Concealment of sexual abuse: “The parents of a child knew that their child had been sexually abused, but they chose not to disclose it out of fear of being disgraced. Later, they shared their experience during a meeting with us” (Participant #8).

- Refusal of the educational system to teach sexual issues: “Since children and adolescents don’t receive education on sexual issues, they often try to learn about these topics from their peers. Unfortunately, this usually leads to misinformation and increases the likelihood of their exposure to sexually explicit content” (Participant #3).

4.3.2. Ineffective Parent-Child Interactions

- Parental conflicts: “I had a client who mentioned that his parents had a heated argument over an old issue and even threatened to divorce. This teenager turned to his mobile phone for comfort, which led to watching porn videos and eventually becoming addicted to them” (Participant #1).

- Parenting styles: “One of my clients shared that because his parents did not monitor his internet usage, he joined a Telegram group introduced by a classmate late one night. For the first time, he was exposed to sex chats and online porn videos. He said that if his parents had supervised him more closely, he might never have joined such groups” (Participant #12).

The use of online social media and networks by children and adolescents, regardless of their age group, and early exposure to unsafe cyberspace: “Just like computer games that are designed based on children’s age groups, it would be much better if there were specific rules for the use of websites by children and teenagers, along with some age requirements for owning a personal mobile phone” (Participant #9).

Punishment and deprivation: “One of my clients, a teenage boy, told me that after he had watched porn for the first time purely out of curiosity, his father found out and treated him badly, even beating him with a belt. He felt terrible, and from then on, he became more curious to see more porn and sought it out again. Of course, this is how he [the client] interpreted the story” (Participant #10).

4.4. Harms of Unsupervised Cyberspace

4.4.1. Paving the Way for the Occurrence of Psycho-Social Harms

- Occurrence of sexual disorders: “One of the clients said that whenever she is ready to have sex, her husband refuses and masturbates with some special tools. The husband also says that he has become accustomed to it. He has been watching porn movies since he was a child, and now he would also like to watch porn movies online” (Participant #2).

- Occurrence of anxiety, depression, and PTSD: “Exposure to inappropriate sexual content can cause a person to suffer from stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD” (Participant #6).

- Academic failure: “Traumas caused by online sexual abuse usually lead to anxiety, behavioral and psychological problems, sleep disorders, and academic failure” (Participant #14).

- Poor self-esteem: “I had a client whose sexual videos were released by her boyfriend. She said that whenever she walks down the street, she thinks that everyone is looking at her or talking about her porn videos, and she feels very bad” (Participant #11).

- Suicide attempts: “I had a client who stated that she lived in a strict and prejudiced family atmosphere. She was threatened by her boyfriend that he would release her private photos in family groups. Thus, she decided to commit suicide and end her life before her father and brothers could do it” (Participant #15).

4.4.2. Early Sexual Awakening

- Seeking approval from virtual people: “Many children and teenagers are looking to gain more likes or approval from others on social and online platforms” (Participant #14).

- Satisfying curiosity: “Well, children don’t know anything either, and this makes them use social online platforms and networks to learn the things that we didn’t teach them. Out of curiosity, they may end up on websites with sexual content to learn about sexual issues” (Participant #3).

- Addiction to masturbation: “One of my clients was a boy who had been brainwashed because of his relationship with a girl, and he was constantly involved in masturbation, sex chat, and video calls” (Participant #13).

4.5. Awareness and Clarification as the Keys to Finding Preventive Support

4.5.1. Raising Parents’ Awareness About Sexual Issues and Physiological Changes in Children and Adolescents

“Making families and parents aware of children’s physiological changes should be taken into consideration” (Participant #9).

- Teaching the psychological mechanisms of puberty and children’s sexual curiosities: “Like other countries in the world, Iranian parents should receive training on the psychological mechanisms involved in puberty, as these may cause some problems for children” (Participant #7).

4.5.2. Educating Parents

- Establishing a good relationship with children: “Establishing a safe relationship between the child and the parents is a very effective factor in preventing online sexual abuse. Raising parents’ awareness of how to use social media and the internet can also be effective” (Participant #15).

4.5.3. Physical and Emotional Support from Parents

- Parental awareness of children’s needs: “Good parents should understand that they need to spend adequate time getting to know their children and adolescents and addressing their various needs. In addition to fulfilling their physical and nutritional needs, parents should also be aware of their children’s psychological needs and their tolerance levels” (Participant #4).

4.5.4. Child Supervision

- Lack of supervision: “One of my clients mentioned that they have no control over their children, and their daughter is always in her private room with no interaction from them” (Participant #1).

4.5.5. Setting Restrictions and Rules

- Absence of family rules: “Sometimes, parents have no control over their children, and there are no rules in the family. As a result, children do whatever they wish, which may lead them to sexual abuse” (Participant #5).

4.5.6. Seeking Professional Consulting Support

- Supervision by the school counselor: “School officials and counselors have little control over children’s issues and problems, and many matters related to child sexual abuse go unnoticed” (Participant #10).

- Referral to psychotherapy and counseling centers: “Some students who have experienced sexual abuse should be referred to counseling and psychotherapy centers to receive specialized clinical services” (Participant #1).

- Holding sex education workshops in kindergartens and schools: “Preschool children should receive training about their bodies and private parts. They should also be taught who is allowed to touch their body parts and who is not” (Participant #14).

5. Discussion

The present study examined the experiences, underlying factors, consequences, harms, and strategies to prevent online child sexual abuse from the perspective of experts in the field. The findings indicated that online child sexual abuse includes requesting photos and videos, engaging in sex chatting, conducting sexual activities through video calls, displaying children’s photos by parents, and contacting children using fake profiles. Similarly, Nova et al. (9) demonstrated that criminals can take screenshots, save photos and videos, and later use them for online sexual abuse, particularly of private nature, in chats. Moreover, Arfini et al. (10) found that most internet criminals conceal their real identities during interactions with children and teenagers by using fake profiles, which are harder to trace.

The present study also explored the factors underlying online child sexual abuse, and the findings indicated that non-updated textbooks, free access to VPNs, advertisements on websites and channels, unrestricted access to pornographic content, online courses, parents' preoccupation with financial issues, parents' excessive use of social networks, family shame regarding the expression of sexual issues, the concealment of sexual abuse, the taboo surrounding sexual issues in the community, the refusal of the educational system to teach sexual issues, family conflicts, parenting styles, early exposure to cyberspace, and physical punishment can all contribute to online child sexual abuse. Similarly, Warren (11) showed that due to social taboos and rejecting parenting styles, most victims avoid disclosing sexual incidents to their parents. Children are exposed to online sexual abuse for several reasons, including insufficient parenting support, inadequate legal protection (12), and a lack of knowledge about safe internet usage. Emery et al. (13) also found that children who were neglected by their parents had 11.2 times the likelihood of being sexually abused offline and were 3.5 times more likely to be exposed to online sexual abuse. Furthermore, Jonsson et al. (14) identified a strong relationship between factors such as low self-confidence, poor relationships with parents, substance abuse, psychological difficulties, the desire to engage in risky behaviors online, and exposure to online sexual abuse.

Another contributing factor identified was the easy access of children to VPNs, which allows them to access websites from all over the world. As a result, it appears that internet service providers should impose filters to block access to websites containing CSAM and other harmful content. Steel et al. (15) suggested that parents should be encouraged to install parental controls on their children's devices, such as smartphones and laptops, to limit access to inappropriate online content. These controls can be used to block websites containing sexual and harmful content and to monitor children's online activities for better supervision. The findings of the present study also indicated that online education during the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to online child sexual abuse. During the pandemic, internet usage increased by 50% in several European countries (16). Harris et al. (17) also showed that in the first six months after the quarantine in England, there was a 17% increase in online sexual crimes against children.

The present study also examined the consequences and harms of online child sexual abuse, including the occurrence of sexual disorders, anxiety, depression, worry, poor self-esteem, academic failure, suicide, seeking approval from virtual people, satisfying sexual curiosity, and masturbation. Various studies have addressed the harms and consequences of online sexual abuse. For example, Pedersen et al. (18) found that mental health problems, low self-confidence, and conflicting relationships with parents are associated with risky online behaviors and sexual abuse. Hailes et al. (19) also reported that children involved in online sexual harassment experience varying degrees of anxiety, depression, and PTSD. Turner et al. (20) suggested that online child sexual abuse leads participants to feel empty and helpless. Academic failure was another consequence of online child sexual abuse. Keeley and Little (21) showed that when children aged 11 to 16 are restricted from spending too much time on their mobile phones, their academic performance improves.

The present study also highlighted that satisfying curiosity was one of the factors contributing to online child sexual abuse. Soldino and Andrés-Pueyo (22) found that adolescent developmental characteristics, such as curiosity about sex, a willingness to take risks, and the initiation of sexual experiences, can increase adolescents' vulnerability to online sexual abuse. Moreover, in many cases, children who have been sexually abused engage in risky sexual behaviors during adolescence. They may have multiple sexual partners, engage in sexual exchange, and even seek primary sexual experiences, which increases their vulnerability to sexually transmitted diseases (23).

Finally, the present study addressed preventive strategies for online child sexual abuse, and the findings highlighted the role of education in its prevention. Moreover, sexual education, teaching physiological changes, education through games and demonstrations, teaching the psychological mechanisms of puberty, addressing children's sexual curiosities, interacting and communicating with children, monitoring children, providing physical and emotional support from parents, establishing a good relationship with children, setting restrictions and rules within the family, supervision by school counselors, referring sexually abused children to psychotherapy and counseling centers, and holding sex education workshops in kindergartens and schools have all been shown to be effective in preventing online child sexual abuse.

Furthermore, prevention programs should focus on websites that contain adult content. Such content should be restricted based on age verification requirements to prevent children from accessing sexually offensive material. For example, users should be required to provide proof of age. A study by the European Commission (EC) found that age verification requirements are effective in reducing children's exposure to inappropriate online content (24). Carr et al. (5) stated that law enforcement agencies should require local telecommunications and information technology providers to block and report websites that regulate child pornography, limit children's access using specific URLs, track website addresses and IPs, and block access to websites that distribute pornographic content.

In addition, education in schools and kindergartens appears to be a key factor in preventing online child sexual abuse. Organizing school-based programs can also increase children's awareness of the risks of online sexual abuse through age-appropriate activities and programs.

A study conducted by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) in the United Kingdom found that school-based educational programs were effective in increasing awareness of online safety among children and adolescents, as well as in reducing the risk of online sexual abuse (25). Additionally, the formation of a sexual harassment prevention committee in every educational institution and school, including a school counselor and psychologist, can help raise awareness of online sexual harassment. Furthermore, workshops and training courses can be held for teachers, parents, and local communities to educate them about online child sexual abuse and its prevention. A study conducted by the IWF showed that training programs for parents and teachers are effective in reducing the risk of online sexual abuse among children (26).

The findings from the present study emphasized the importance of education and awareness-raising for both parents and children. In this regard, public awareness campaigns can be launched through various media platforms, such as television, radio, and print media, to reach a wider audience and educate them about online sexual abuse and how to prevent it. A study by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) found that public awareness campaigns were effective in raising awareness of online sexual abuse and encouraging victims to participate in such campaigns (27). The researchers suggested that, to prevent child sexual abuse, it is essential to educate both children and parents about social sites and networks. Children who are exposed to the risk of online sexual abuse should be supported by their parents and receive psychological guidance and treatment (28).

A UNICEF report (29) indicated that children engaged in various online activities require more advanced internet skills. However, children in low-income countries such as Bangladesh often lack opportunities to acquire adequate knowledge of digital technologies. Moreover, Bangladeshi parents themselves lack sufficient knowledge about the safe use of the internet and are unaware of how children are being exploited through online platforms, making it difficult for them to protect their children. Although several parental control software tools are available, parents are not adequately trained to use them.

Overall, studies have shown that when parents discover that their children are at risk of online sexual exploitation, they may experience a range of emotions, such as anger, intense stress, fear, and blame. Psychologists suggest that anger and blame can have adverse consequences. In such situations, parents should reassure their children by offering help, support, and encouragement, assuring them that they will be protected and that no one can harm them. Building digital resilience is another key approach to combating online child sexual abuse. Parents, and even teachers, should work to enhance children's ability to recognize risks and help reduce the potential for online sexual abuse (25).

However, in line with the findings of the present study, to prevent online child sexual abuse, internet literacy programs should be implemented for primary and high school children. Such programs empower children with the knowledge to use the internet more safely (30).

Additionally, given the legal gaps that have contributed to the rise of online child sexual exploitation, preventive and up-to-date laws should be enacted to address this emerging issue. Support and psychological interventions should also be planned and implemented for affected children. Moreover, relevant organizations and institutions need to launch programs and campaigns using both social media and traditional platforms to raise children’s awareness of online sexual abuse. These awareness-raising programs should be tailored to the age requirements of children, be of high quality, and be delivered on safe internet platforms.

The results of this research indicate that an unsafe and unsupervised cyberspace can pose a serious threat to children’s online sexual abuse. The findings can help in developing knowledge and media literacy, as well as in securing the virtual space and content of social networks for children and teenagers. Additionally, the preventive measures suggested by experts and stakeholders in this field—including educating parents, educators, children, and teenagers about the potential dangers of online sexual abuse—could lead to changes in social and educational policies, as well as the adoption of relevant laws. However, the results of this research have limitations in terms of generalizability due to the abstract nature of the concepts in qualitative research, as well as the geographical area, social conditions, and the limited number of participants.