1. Background

The psychological and sociological effects of violence against women are critical concerns in women's mental health. Domestic violence is the most prevalent form of violence against women. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), violence is defined as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, and psychological harm" (1, 2). Approximately 28% of women in developed nations report experiencing physical violence by their spouses at least once in their marital life. This figure ranges from 18% to 67% in developing countries (3). In 2008, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education in Iran reported that the prevalence of domestic violence against Iranian women was approximately 65%. In Tehran, the prevalence of domestic violence against pregnant women was 60.6%, including emotional abuse (60%), physical abuse (6.14%), and sexual abuse (5.23%) (4). Furthermore, research conducted in Sistan and Baluchestan province, particularly in Zahedan, indicates that a significant majority of married women—ranging from 62.7% to 83%—have reported experiencing violence from their husbands (5, 6).

Violence against women by men encompasses multiple aspects, including physical abuse (injuring the body through hitting, assault, and battery by hand or other objects), mental abuse (threatening, humiliating, verbal abuse, and cursing), social abuse (controlling behavior and isolation), and sexual abuse (7). A wide range of women, at different stages of their lives, experience domestic violence. Pregnant women account for more than one-third of domestically abused women who seek medical attention, as they are more vulnerable to domestic violence. Therefore, they must be screened more carefully for domestic violence (8). The most significant causes of violence in the family include low family income (as the most critical cause), the environment in which the man and woman were raised, addiction and criminal records, inadequate family support for the woman, insufficient dowry, religious differences, and addiction (such as smoking) (9). Domestic violence during pregnancy poses severe risks to both the mother and the fetus, including frequent hospitalization of the mother, increased mortality rates, various complications and disabilities, unusual vaginal bleeding, urinary tract and chronic pelvic infections, stillbirth, abortion, preterm delivery, and low birth weight (10-13). Moreover, some researchers have found a positive correlation between violence against women and unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (11).

Violence against women has grave consequences. Mothers may not commit to raising their children, may give birth to babies with low birth weights, and may develop various physical and mental problems. Even if they do not self-intoxicate, they might become infertile, die during childbirth, commit suicide, or fall victim to their spouses. Violence against pregnant women not only endangers their physical and mental health, impairing their ability to perform social duties, but also, depending on ethnic values and circumstances such as divorce and separation, polygamy, and a high number of children, causes women to suffer multifaceted damaging effects. These effects can reflect on their children's IQ and job educability, impacting society as a whole (14).

2. Objectives

Additionally, among other consequences of this cultural and social health problem, there is an increase in medical care costs due to physical and mental complications arising from the woman’s experience of violence. This can also lead to a reduction in women’s social productivity. Despite the severity of this issue, little statistical information is available on these women. Due to the importance of this issue and its consequences, this study investigated the causes and consequences of violence against women in Zahedan, using data gathered from pregnant women who presented to Zahedan medical centers and OB/GYN specialists. It is essential to mention that not much research has been conducted in Zahedan on this subject, highlighting the need for such a study.

3. Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study involved pregnant women who were referred to the maternity ward of Zahedan Ali Ibn Abitaleb Hospital and were enrolled via convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Age 18 - 35 years, pregnant, married, parity ≤ 4, normal weight gain during pregnancy, and a single fetus in cephalic presentation. The exclusion criteria included a history of smoking, alcohol and narcotics consumption, miscarriage during the first trimester, a fetus with malformation, multiple pregnancy, history of preterm delivery, and repeated abortions. The sample size was calculated using the formula n = z² p (1-p)/d², with parameters set at P range of 18 - 67%, α = 0.04 and z = 1.96. This resulted in a sample size of n = 384. To account for potential missing patients, the final target was set at 400 participants for the study.

Initially, demographic information about the patients, including age, education level, and income disparities of the couples, was gathered. Subsequently, the patients completed a questionnaire assessing violence against women by their spouses. This questionnaire consists of 17 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale and is divided into categories of physical, sexual, mental-emotional, and financial violence. The validity of the questionnaire was assessed in the study by Mehri et al., which reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.86 (15).

The clinical characteristics of patients, including factors such as gravidity, parity, live births, and histories of abortion, molar pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies, premature labor, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), low birth weight, fetal death, neonatal death, and postpartum hemorrhage, were documented by obstetrics and gynecology using a researcher-designed checklist. Once data were collected from all the pregnant women, it was analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA) in accordance with the study's objectives. The demographic and clinical characteristics were examined using frequency distribution analyses. Furthermore, categorical variables were evaluated using the chi-square test. Confidence intervals were determined, with a significance level established at a P-value of 0.05.

4. Results

Four hundred pregnant women from the maternity ward of Ali Ibn Abitaleb Hospital in Zahedan, who met the inclusion criteria, were enrolled in this study via convenience sampling. They completed the questionnaires, including the demographic form. According to Table 1, among the 400 pregnant women in this study, 335 patients (83.75%) had experienced at least one aspect of domestic violence, while 65 patients (16.25%) did not have such an experience.

| Domestic Violence | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Yes | 335 (83.75) |

| No | 65 (15.25) |

| Total | 400 (100) |

Frequency Distribution of Domestic Violence Among Pregnant Women in Zahedan

According to Table 2, 243 patients (72.5%) had experienced all types of domestic violence, including physical, sexual, mental-emotional, and financial violence. Among the participants, 85.5% had experienced physical violence, 88.9% had experienced sexual violence, 77.9% had experienced mental-emotional violence, and 89% had experienced economic violence.

| Type of Abuse | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Physical | 287 (85.6) |

| Sexual | 298 (88.9) |

| Mental-emotional | 261 (77.9) |

| Financial | 300 (89.5) |

| Experience any type of violence | 243 (72.5) |

Frequency Distribution of Different Types of Abuse Among Pregnant Women in Zahedan

Table 3 shows the frequency of differences in education level among pregnant women and their spouses in relation to their experience of domestic violence. According to the chi-square findings, there was no significant difference (P = 0.59).

| Variable | Difference in Education Level | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | ||

| Domestic violence | 0.59 | |||

| Yes | 121 (36.1) | 214 (63.8) | 335 (100) | |

| No | 27 (41.5) | 38 (58.4) | 65 (100) | |

The Relationship Between Education Level Difference and Domestic Violence Among Pregnant Women in Zahedan a

Table 4 shows the frequency of differences in income among pregnant women and their spouses in relation to their experience of domestic violence, demonstrating a significant difference. In other words, women with an income different from that of their spouses experienced more domestic violence (P = 0.05).

| Variable | Income Difference | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Total | ||

| Domestic violence | 0.05 | |||

| Yes | 281 (63.8) | 54 (16.2) | 335 (100) | |

| No | 34 (52.7) | 31 (47.6) | 65 (100) | |

The Relationship Between the Couple's Income Difference and Domestic Violence Among Pregnant Women in Zahedan a

Table 5 shows that the age differences between couples and the occurrence of domestic violence failed to demonstrate a significant relationship (P = 0.27).

| Variable | Couple’s Age Difference | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 - 5 | 5 - 10 | 10 - 15 | 15 - 20 | ||

| Domestic violence | 0.27 | ||||

| Yes | 112 (33.4) | 89 (26.5) | 81 (24.1) | 53 (15.8) | |

| No | 28 (43.1) | 21 (32.3) | 14 (21.5) | 2 (3.1) | |

The Relationship Between Age Difference and Domestic Violence Among Pregnant Women in Zahedan a

Table 6 shows the frequency of pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with and without the experience of domestic violence. There was a significant relationship between domestic violence and pregnancy outcomes (P = 0.001).

| Domestic Violence | Abortion | Preterm Delivery | PROM | Low Birth Weight | Fetal Heath | Placental Abruption | Postpartum Bleeding | Neonatal Death | Maternal Mortality | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 54 | 142 | 159 | 186 | 37 | 53 | 23 | 12 | - | 0.001 |

| No | 6 | 15 | 21 | 27 | 5 | 7 | 3 | - | - | |

| Total | 60 | 157 | 180 | 213 | 42 | 60 | 26 | 12 | 0 |

The Relationship Between Domestic Violence and Pregnancy Outcomes Among Pregnant Women in Zahedan

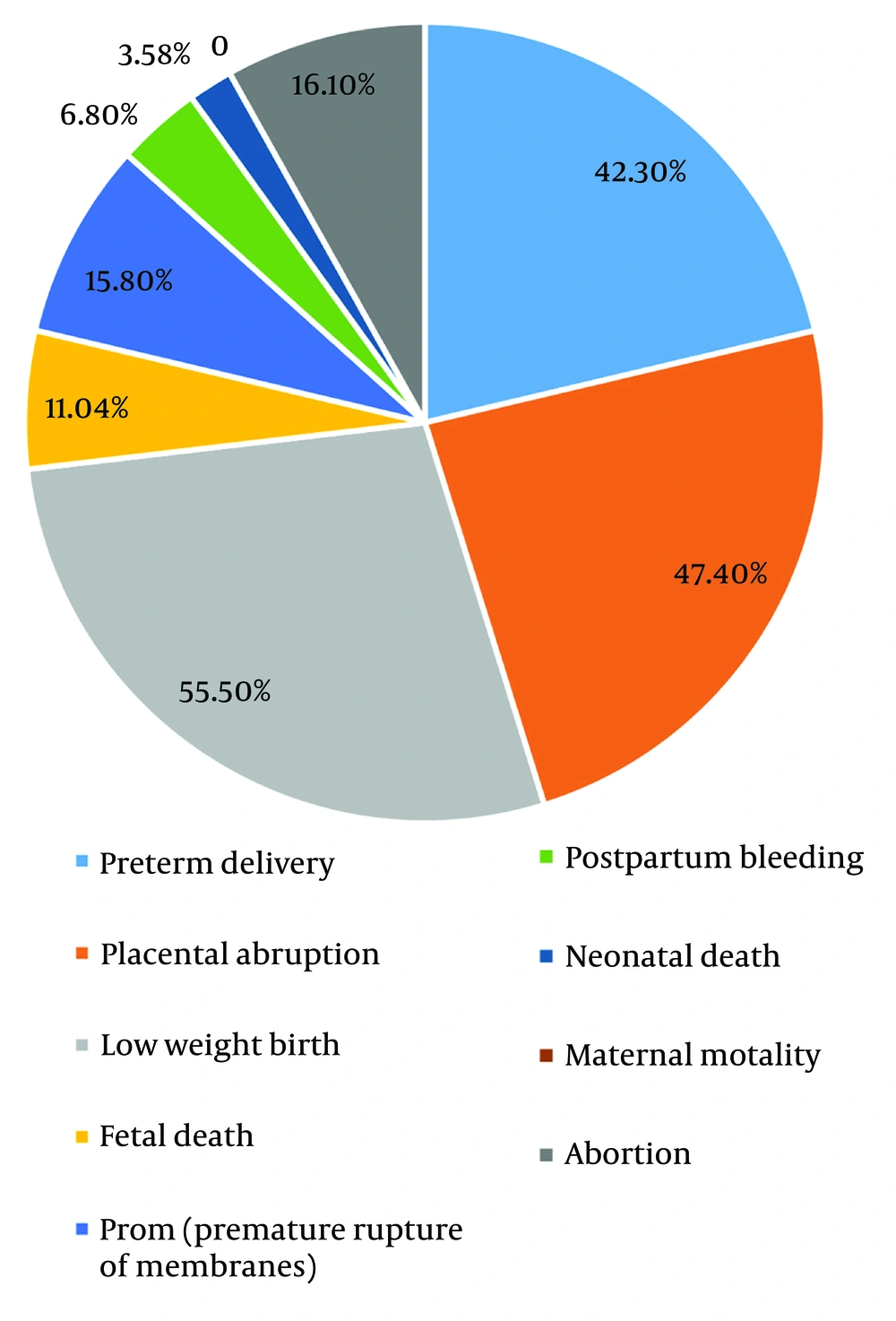

Figure 1 shows the frequency percentage of pregnancy outcomes in women experiencing domestic violence in Zahedan. The data revealed a high prevalence of maternal complications, including low birth weight affecting 55.50% of participants, PROM in 47.40% of cases, and preterm delivery occurring in 42.30% of women. Additionally, abortion rates were noted at 16.10%, while placental abruption impacted 15.80% of participants. Fetal death occurred in 11.04% of cases, and postpartum hemorrhage affected 6.80% of women. The study further indicated a neonatal mortality rate of 3.58%.

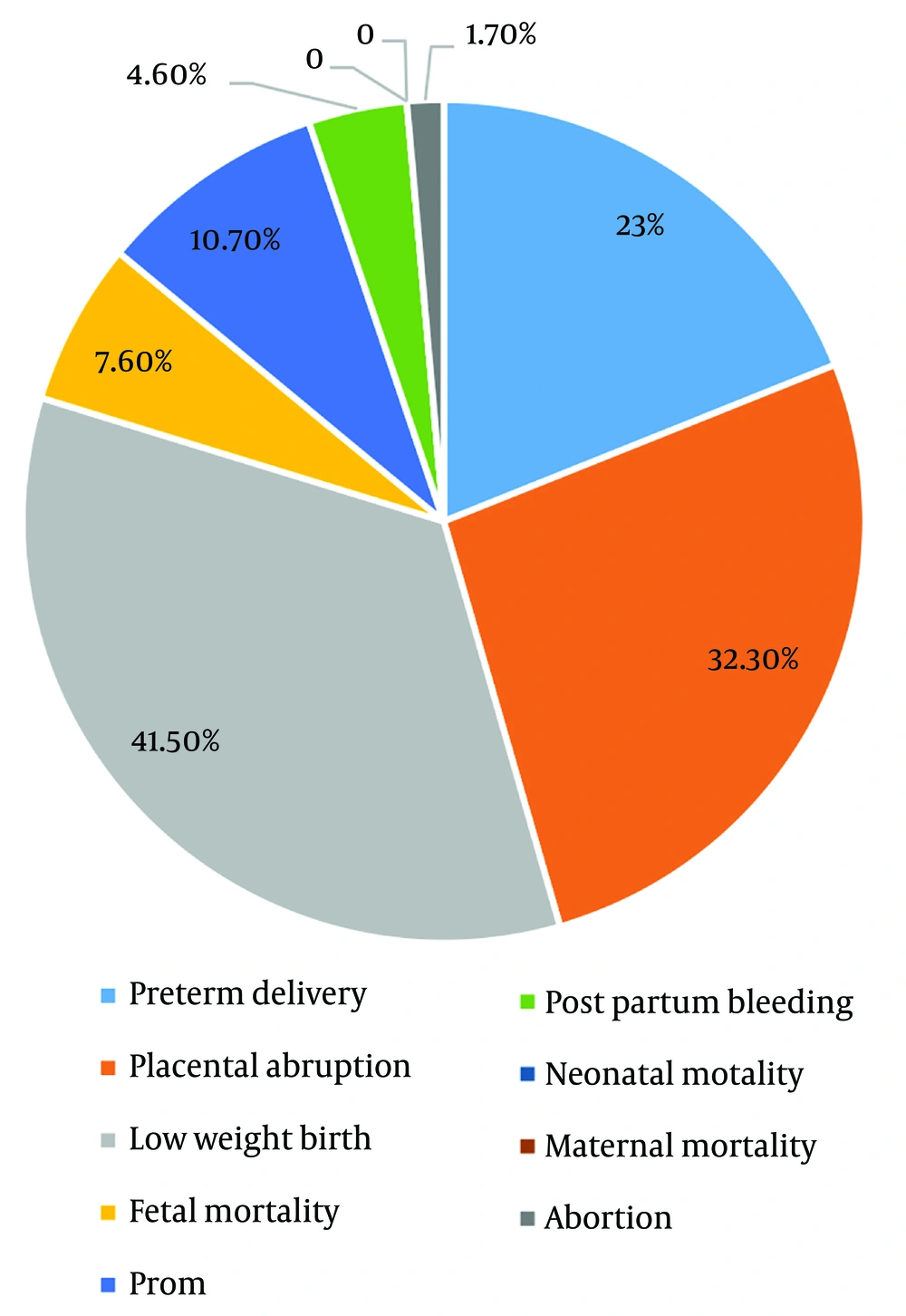

Figure 2 shows the frequency percentage of pregnancy outcomes in women without the experience of domestic violence in Zahedan. The data showed low birth weight affecting 41.50% of participants, placental abruption in 32.30% of cases, and preterm delivery occurring in 23% of women. Additionally, abortion rates were noted at 1.70%, while PROM impacted 10.70% of participants. Fetal death occurred in 7.60% of cases, and postpartum hemorrhage affected 4.60% of women.

5. Discussion

One of the concerns related to women’s mental health is the psychological and sociological effects of domestic violence against women. Domestic violence, defined by the WHO as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, and psychological harm”, is the most common form of violence against women (1, 2). Domestic violence includes any physical, sexual, emotional, and verbal abuse within the family. Women are susceptible to abuse, and this susceptibility worsens during their reproductive years (16). According to the WHO, 16% - 52% of women are exposed to sexual abuse by their spouses. Approximately 28% of women in developed countries and 67% in developing countries report being physically abused at least once (17). Domestic violence might result from misconceptions about pregnancy, the spouse’s unusual feelings toward pregnancy, and decreased sexual activity (14, 18). Recent studies show that generally, 4% - 37% of women experience violence during pregnancy, while many had not experienced violence before pregnancy (19).

Considering the importance of the subject and the consequences of violence against pregnant women, this study investigated the causes and outcomes of this violence against women in Zahedan. Data were gathered from pregnant women at Zahedan Ali Ibn Abitaleb Hospital. The findings showed that 83% had experienced domestic violence. Of these women, 72.5% had experienced all types of abuse. The most common type was economic abuse (89.5%), followed by sexual abuse (88.9%) and physical abuse (85.9%). The results suggested that there was no significant relationship between education level and age differences in marriage and domestic violence. However, there was a significant relationship between income differences in marriage and domestic violence (P = 0.05). The most common pregnancy outcomes of domestic violence were reported to be low birth weight (55.50%) and placental abruption (47.40%), indicating a significant relationship between pregnancy outcomes and domestic violence (P = 0.001).

Some findings showed a significant relationship between violence and variables such as women’s age at marriage, number of children, family’s financial status, the support of the woman by her family, and her smoking status. Domestic violence against pregnant women in all three counties was highly prevalent (20, 21). Our study showed a significant relationship between a couple’s income gap and domestic violence. However, there was no relationship between domestic violence and either age or differences in their level of education.

Mohammadi et al.’s study, titled "The Reproductive Health Status of Women with Experience of Violence in Harm Reduction Centers in Tehran, 2010", investigated the reproductive health of 69 women who had experienced at least one form of violence. The findings showed that among these women, 3.69% had experienced all three types of violence. Of the studied women, 6.86% reported emotional violence, 76% reported sexual violence, and 3.85% reported physical violence. In addition, 6.86% had a history of abortion, and 9.62% had a history of unintended pregnancy. They were also observed to have experienced sexual dysfunction and engaged in anal and oral sex (22).

Our study also showed that 83.7% of pregnant women had experienced domestic violence, among whom 72.50% had experienced all types of violence. According to the findings, 89.50% had experienced economic violence, 88.90% had experienced sexual violence, 85.90% had experienced physical violence, and 77.90% had experienced emotional violence. There is a report about the effect of domestic violence against pregnant women on their pregnancy outcomes. The results showed significant differences among total domestic violence, mental and verbal abuse, sexual abuse, and physical abuse. There was a significant relationship between verbal and mental abuse and reduced birth weight, sexual abuse and PROM, and physical abuse and abortion after the twelfth week of pregnancy (23). Our study also confirmed a significant relationship between domestic violence and pregnancy outcomes (P = 0.001).

Bacchus et al. studied 200 women at London training hospitals and reported a significant relationship between spouse abuse and abortion, sexual injury, and preterm delivery (24). Our study confirmed the relationship between domestic violence and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Additionally, Navvabi Rigi et al. highlighted a correlation between psychological and sexual violence and the occurrence of low birth weight in newborns (25), which is consistent with our findings.

Stockl et al., with a research population of 24,000 in Tanzania, investigated two groups: Women subjected to violence and those free from violence, examining age, socioeconomic situation, and the number of successful births. The results showed that violence by sexual partners had a strong effect on abortion and miscarriage (26).

In the study by Ismayilova and El-Bassel, titled "Intimate Partner Physical and Sexual Violence and Outcomes of Unintended Pregnancy among National Samples of Women from Three Former Soviet Union Countries", conducted in Azerbaijan, Moldova, and Ukraine, where abortion was legal and also practiced as a method of contraception, it was found that women who had experienced physical and sexual violence by their partners were more at risk for abortion and unintended births (27). Our findings also showed that women experiencing domestic violence had a higher incidence of abortions (16.10%) compared to those not experiencing domestic violence (1.70%).

Hajikhani Golchin et al. conducted a study on the demographic, social, and economic characteristics of 301 pregnant women who had been exposed to domestic violence. Their results showed that 5% - 34.0% experienced mental abuse, 28.20% experienced physical abuse, and about 4% experienced sexual abuse (28). Our study showed economic violence (89.50%) to be the most common type of domestic violence and emotional-mental violence (77.90%) to be the least common.

5.1. Conclusions

The study results indicate a high incidence of domestic violence among pregnant women, with an increased frequency observed in those experiencing income disparities with their spouses. Economic violence was identified as the most prevalent form of domestic violence, followed closely by sexual violence. The exposure to domestic violence during pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

5.2. Limitations

The findings may be influenced by social, economic, cultural, and regional factors, which could affect the outcomes. Additionally, the generalizability of the results to other populations is limited, particularly in regions with different cultural or social contexts. The cross-sectional design of our study restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between domestic violence and pregnancy outcomes.