1. Background

Approximately, 3000000 cases of child maltreatment are reported each year, and about one-third of them are substantiated. Victims of abuse comprise a significant proportion of all child psychiatric admissions, with an estimated 30% incidence in lifetime physical and sexual abuse among child and adolescent outpatients, and as high as 55% among psychiatric inpatients (1).

Many abused children experience chronic symptoms of psychopathology (2). Children who have been abused or neglected are at greater risk of developing cognitive, emotional, social, and behavioral problems, which may worsen as the child grows from infancy into adulthood (3-5). A history of child abuse has been associated with future psychiatric disturbances (6), depressive disorder, and more life problems in adulthood (7). Childhood history of physical abuse is associated with an increase in depression, anxiety, anger, physical symptoms, and also medical problems (8).

Abusing parents use punitive and destructive methods, which result in more behavioral problems in their children (9). They have fewer positive interactions with their children (10) and often lack the necessary parenting skills that originate from their childhood experiences (11). Poor parenting has some biological impacts on the child; therefore, some interventions are needed to improve the quality of parent-child relationships in many situations, and it might lessen the biological effects of poor parenting (12).

Several interventions have been applied for abused children and their parents. Some interventions have focused on children while some programs have focused on the abusing parents through cognitive behavioral treatment (13). Also, family-centered studies have been used to decrease child abuse by attempting to raise parental knowledge about anger management, parenting skills, changing beliefs, and stress reduction (14-16). These methods include cognitive behavioral treatment focused on child abuse (17), modifying child-mother interactions (18), combining cognitive behavioral treatment for parent and child (15), and positive parenting methods (19).

Many interventions are used for abusive parents. Almost all parenting programs are designed to help parents develop more appropriate expectations of their children, to learn how to be empathetic and nurturing parents, and to use positive discipline instead of physical punishment (20). Parent training programs (PTPs) aim to change parenting practices to promote children’s psychosocial development (21). Reviews and meta-analyses support the efficacy of PTP on improving parenting skills and children’s behavior (22-24). Literature review suggesting that PTPs are associated with improvement in parents’ behavior (13, 25-28). Researchers in the field of child abuse and neglect agree that PTPs are also relevant in a protection care context. Indeed, skills targeted by such programs reduce the risk of abuse or neglect (27, 29).

The positive parenting method of Sanders is one of the most common types of applied intervention programs. This method is based on a social learning model and can be effective and feasible in children with maladaptive behaviors (30). It is not only recognized as the most useful method for children with misbehavior and conduct problems (19), but also has been effective in decreasing child abuse between members of a family (31).

Parent management training has positive impacts on both parents and children. The effect on children has been assessed in another article, and this study focuses on the parents. We conducted this study to evaluate the effectiveness of therapeutic intervention and parent management training on improving parenting skills of abusive parents.

2. Objectives

The present study was conducted to examine the effects of therapeutic intervention and parent management training on parenting skills of abusive parents.

3. Patients and Methods

This study is quasi-experimental and conducted at the clinic of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of Imam Hossein Hospital affiliated with Shahid Beheshti Medical University in Tehran, Iran. To participate, parents and children must comply with all requirements of the study by giving written informed consents after reading the procedures and purposes of the study. It was given under procedures approved by the hospital's Institutional Review Board.

3.1. Subjects

The study group included children and their parents who had been referred to the Emergency Room and Pediatric and Child Psychiatric Clinics of Imam Hossein Hospital from October 2008 to March 2009 diagnosed with child abuse. Participants’ age ranged from infancy to 18 years old. The intervention phase lasted 3 months, but participants were followed for 6 months. The subjects were evaluated at the beginning, and then at the third and sixth month (up to 3 months after ending the intervention).

3.2. Design and Procedures

The participants were found through a child abuse questionnaire or from discovering signs of abuse during examination of the child by a pediatrician or psychiatrist. Next, they were introduced to the coordinator of the project. The parents were required to fill a consent form at this stage. Demographic data were collected through a questionnaire and then the children and their parents were referred to the psychiatrist for assessment. The psychiatrist assessed the children by DSM-IV-TR (diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder, fourth edition- text revision) criteria and K-SADS (Kiddie-schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia), and the parents using DSM criteria and SADS. Child rearing styles were obtained by administering ‘Being a Parent’ (32) and ‘Parenting’ scale (33) which have been used in some researches in IR Iran (34).

Parents and children were visited by a child psychiatrist regularly, and therapeutic interventions (prescription drugs and psychotherapy) were done based on their individual needs and psychiatric disorder. All the parents participated in the designed project intervention package. This package consisted of 8 weekly sessions. Each session lasted 90 minutes with 8-10 participants. The first session was psycho-education about child abuse, including definition of child abuse, its kinds, negative consequences of abuse, and physical punishment as a non-effective method for children's misbehavior. The second session included anger management skills. The remaining 6 sessions revolved around parent management training and were explained according to level 4 Triple P (31). Topics of sessions included positive parenting, causes of children’s misbehavior and monitoring of children’s behavior (one session), positive relationship with children and encouraging desirable behavior (one session); introducing rules, giving instruction (one session), managing misbehavior by ignoring, logical, appropriate consequences and time out (two sessions), and managing high-risk situations (one session). The sessions were managed by a trained psychologist and supervised by a child psychiatrist during the project.

The parents were assessed using parenting style questionnaires (Being a Parent and Parenting scale) at the first meeting (before intervention), and then at 3 and 6 months later.

The questionnaire of ‘Being a Parent’ measures feelings of satisfaction and competency with regard to parenthood with 16 items (32). The ‘Parenting scale’ evaluates parental reaction towards misbehaviors of children. It has 30 items. Each item has a Likert score from 1 to 7; a low score shows appropriate parenting, and a high score indicates inadequate parenting. This scale is based on the following three factors: laxness, overreactivity and verbosity. Some items do not refer to any of these factors (33, 35).

3.3. Statistical Analysis

To analyze the data, descriptive statistics were used, including mean, standard deviation, and percentage. Repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for the comparison of scale scores at first (zero point time), third month and sixth month.

4. Results

A total of 73 abused children, 30 (41%) girls and 43 (59%) boys with the mean age of 6.9 ± 4.3 y were studied. Fifty-four (74%) children experienced physical abuse, 53 (72.6%) children suffered from emotional abuse, 29 (39.7%) children experienced neglect, and 3 (4.1%) children experienced sexual abuse (Table 1). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder was the most common psychiatric disorder (65.8%) among abused children according to K-SADS and psychiatric interview. Eighty percent of the abused children suffered from a psychiatric disorder and 74% of them had at least two psychiatric disorders.

Mean age of parents was 31.76 ± 6.52 year for the mothers and 38.07 ± 8.45 year for the fathers. About 13.6% of mothers and 10.3% of fathers had a university education, and other parents were less educated. Moreover, 16.7% of the mothers and 92.4% of the fathers had a job. General anxiety disorder and depression were the most common psychiatric disorders in mothers based on SADS and DSM criteria with the prevalence of 22 (30.1%) and 20 (27.4%), respectively. Mothers in 16.7% of the subjects, fathers in 28.3%, and both parents in 53.3% were the abusers (Table 1).

The detailed results of psychiatric diagnosis in children and their parents and other intervention results will come in a separate paper.

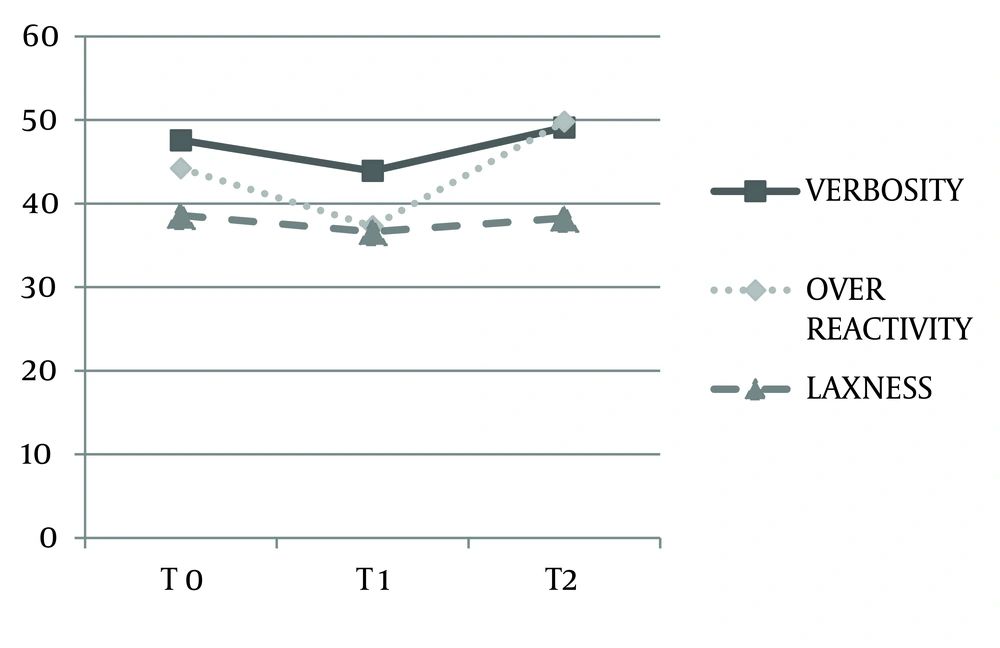

Table 2 shows parenting styles regarding both applied scales (Being a Parent and Parenting Scale) before the intervention. Low scores in the ‘Parenting Scale’ show appropriate parenting and high scores are a result of inadequate parenting. Verbosity has the highest mean score (47.58 ± 7.00) compared with two other subscales of the ‘Parenting Scale’ before the intervention.

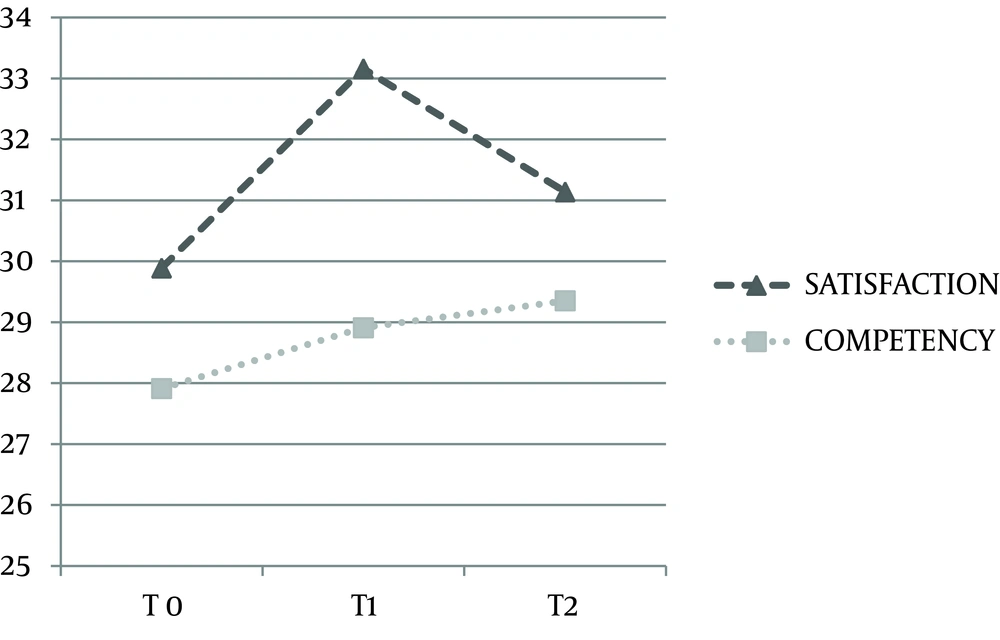

In subscales of ‘being a Parent’ mean score of satisfaction was 29.89 ± 7.29 and competency was 27.91 ± 6.10 before the intervention. Repeated measure ANOVA was used for the comparison of two scales at first (zero point time), third and sixth month (Table 3) after the intervention.

In parenting scale, There were significant differences between zero and third month in all subscales (P = 0.008). There were no significant differences in verbosity (P = 0.06) and overreactivity (P = 0.16) after exerting intervention (6 months); however, changes in verbosity subscale is a trend. Subscale of laxness showed significant changes over these time points (P = 0.03).

With regard to ‘Being a Parent’ scale, there was no significant difference in satisfaction (P = 0.18) and competency (P = 0.16) and total score (P = 0.7) while comparing with repeated measure ANOVA before and after the intervention (Table 4).

| Statistic | |

|---|---|

| Number of children | 73 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 43 (58.9) |

| Female | 30 (41.1) |

| Type of child abuse | |

| Physical abuse | 54 (74) |

| Emotional abuse | 53 (72.6) |

| Neglect | 29 (39.7) |

| Sexual abuse | 3 (4.1) |

| Abusive person | |

| Mother | 10 (16.7) |

| Father | 17 (28.3) |

| Both | 32 (53.3) |

| Others | 1 (1.7) |

| Mean age of parents | Statistic: Mean ± SD |

| Mother | 31.76 ± 6.52 |

| Father | 38.07 ± 8.45 |

| Mean age of children | 6.9 ± 4.3 |

Demographic Data of Subjects a

| Number | Minimum | Maximum | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being a parent | ||||

| Total score | 55 | 30.00 | 85.00 | 57.65 ± 10.53 |

| Satisfaction | 55 | 16.00 | 52.00 | 29.89 ± 7.29 |

| Competency | 56 | 12.00 | 37.00 | 27.91 ± 6.10 |

| Parenting scale | ||||

| Verbosity | 58 | 31.00 | 66.00 | 47.58 ± 7.00 |

| Over reactivity | 58 | 24.00 | 64.00 | 44.22 ± 9.79 |

| Laxness | 58 | 26.00 | 61.00 | 38.58 ± 8.21 |

Parenting Style Scores Based on Being a Parent and Parenting Scale a

| Results | df | F | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verbosity | 2.20 | 3.09 | 0.06 | |

| Before intervention | 47.58 ± 7.00 | |||

| 3 months after Intervention | 43.91 ± 5.97 | |||

| 6 months after Intervention | 49.11 ± 6.58 | |||

| Over reactivity | 2.20 | 2.26 | 0.16 | |

| Before intervention | 44.22 ± 9.79 | |||

| 3 months after intervention | 37.29 ± 11.84 | |||

| 6 months after intervention | 49.81 ± 19.05 | |||

| Laxness | 2.20 | 3.85 | 0.03 | |

| Before intervention | 38.58 ± 8.21 | |||

| 3 months after intervention | 36.63 ± 6.30 | |||

| 6 months after intervention | 38.29 ± 8.94 |

Repeated Measure ANOVA in Subscales of Parenting Scale a

| Results | df | F | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction | 2.26 | 1.80 | 0.18 | |

| Before intervention | 29.89 ± 7.29 | |||

| 3 months after intervention | 33.16 ± 7.29 | |||

| 6 months after intervention | 31.14 ± 6.61 | |||

| Competency | 2.22 | 2.26 | 0.16 | |

| Before intervention | 27.91 ± 6.10 | |||

| 3 months after intervention | 28.91 ± 5.33 | |||

| 6 months after intervention | 29.35 ± 5.18 | |||

| Total | 2.22 | 0.34 | 0.7 | |

| Before intervention | 57.65 ± 10.53 | |||

| 3 months after intervention | 61.79 ± 11.52 | |||

| 6 months after intervention | 60.25 ± 9.96 |

Repeated Measure ANOVA in Subscales of Being a Parent Scale a

5. Discussion

This study evaluated the influence of therapeutic intervention and parent management training on improvement of parenting skills of abusive parents. Of subscales of parenting scale, laxness showed significant changes over the study period. Improvement in laxness can be due to education sessions, which emphasized on the importance of having clear, simple, and consistent rules. On the other hand, it appears that environment influences on laxness more than verbosity and over reactivity.

The existence of significant differences between the zero and third month evaluations in all subscales that have not continued up to the sixth months shows that abusive parents need longer intervention or booster sessions to keep the positive effects. Previous studies also mentioned relapse after initial improvement pursuant to parenting interventions and emphasized that studies are needed to see whether, some months after initial treatment, booster sessions should routinely be offered to prevent relapse (12).

On the other hand, 80% of children in our study had at least one psychiatric disorder that makes the parenting more difficult. In fact, child behavioral problems have some negative influences on the parent's ability to undertake care giving tasks (36). It seems that appropriate interventions for reducing child's misbehaviors reduce the burden of care for parents (37) and make them stronger in the parenting role and subsequently decrease the risk of inept discipline and child abuse.

Letarte et al. (21) showed more improvement than our study in parenting skills using the ‘Parenting Practice Interview’, although they found no difference on the measure of parenting self-efficacy feeling.

There are some differences between our study and the Letarte et al. (21) study. They assessed the effectiveness of a parent training program ‘Incredible Years’ in improving parenting practices with longer time, and we used positive parenting program with two extra sessions and shorter intervention phase. We do not know whether or not our results would change if we extended our session. Although in both studies, the questionnaires assessed parenting skills, they were different. Other things that may explain the differences in results may be due to the source of the samples. Our samples were recruited from a psychiatric department and almost 30% of the mothers suffered from general anxiety disorder and depression, and although some parents in our study took other psychopharmacological interventions according to their psychiatric disease, there were no mental illness symptoms in Letarte et al. (21) samples. It may be one of the reasons that parent management training did not induce more improvement in parenting skills in our study. Previous studies also have shown that maternal depression has negative impact on parenting and is associated with the development of behavior problems in children; subsequently, this makes parenting more difficult (38).

However, the results of the present study do not show any effect of the program on the ‘Being a Parent’ scale or satisfaction and competency. It seems that these items originate from attitude and change in attitude requires longer time, so there was not any significant change in satisfaction and competency after 3 or 6 months.

Also previous studies mentioned that many families failed to improve with initial treatment following parenting interventions, indicating perhaps the necessity of systematic procedures to address the difficulties of these families (12). Also, in the Letarte et al. (21) study, there was no difference in the measure of parenting self-efficacy feeling. They believed that more time may be required before change could be observed in these outcomes, especially among parents who had a history of difficult parent–child interaction. Parents may be expected to develop confidence in their parenting skills over time, as they experience more successful interactions with their child (21). Results of this study support the idea that preventive-intervention programs, such as parent training, can reduce harsh disciplines in parents.

The effect of our intervention on child abuse, neglect and child misbehaviors was assessed in another article (39), but our findings in the present study show some degree of improvement in parenting skills following parent management training, and that improvement in parenting practices might lead to fewer situations of abuse or neglect (27, 29).

The duration of intervention and follow-up was short in our study. If we had a longer time with booster sessions, we could find the most effective factors in parenting improvement and decreasing child abuse. It is recommended that future study would address resilience indicators and how to promote resiliency in Iranian families with child abuse.