1. Background

Opioids are a class of drugs with pain relieving properties (1). As such, they are prescribed by physicians for pain relief, including drugs such as oxycodone and hydromorphone. The euphoric feeling caused by opioid use may lead to abuse and dependence (1). Opioid use disorder (OUD), as listed in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition, is a chronic psychiatric disorder, characterized by continued use of opioids despite harmful consequences, leading to impairment in function (2). It is estimated that 3.9% of North Americans use opioids, greater than the global prevalence of 0.7% (3). Of these North American individuals with OUD, only 21.5% receive treatment (4). This leaves a significant proportion of those with OUD unsupported, which puts a strain not only on the individuals themselves, but also on society.

The lack of treatment received by those with OUD is complicated by the comorbidity of OUD with other substance use disorders. In particular, OUD has been known to accompany the use of other substances such as cannabis, alcohol, tobacco, and stimulants (2). Moreover, 35.6% of those with OUD also suffer from cocaine use disorder, while 31.2 - 57.5% of those with OUD are comorbid for alcohol use disorder (AUD) (5-7). Thus, in order to holistically treat individuals with OUD, substance use comorbidities, or polysubstance use, must be considered.

Of those who seek treatment, one common option is Methadone Maintenance Treatment (MMT). Methadone is a long-acting opioid that is prescribed to treat patients with OUD (8). MMT was first introduced in 1964, and has since become one of the most widely used treatments for OUD due to its ability to relieve withdrawal symptoms, and cravings for opioids. Despite such positive results regarding MMT’s effectiveness, studies have found that relapse rates for OUD are high upon completion of treatment. Ball and Ross (9) reported a relapse rate of 82% one year after treatment, while Dole and Joseph (10) reported a relapse rate of 64%. To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted since to update the general rate of relapse amongst OUD patients in MMT. Instead, current research has focused on the relapse rates of specific populations amongst those with OUD, such as incarcerated individuals, and individuals with HIV/AIDS.

Much attention has been paid to family factors as risk factors for developing substance use disorders, and the literature consistently supports this hypothesis (11, 12). However, there is less information on the association, if any, between family factors and illicit polysubstance use amongst individuals with OUD in MMT. In fact, there is no established association on the topic amongst the current literature. Sparse research has been done on the association between family factors and polysubstance use in general, but the literature is unclear on the nature of this association. For example, one study found that participants with two biological parents with a substance use disorder (SUD) were statistically more likely to use both drugs and alcohol than those with one or no such parent (13). However, they also found an inverse relationship between the number of biological parents with substance use disorders and the prevalence of drug-only substance use disorders, which suggests that a family history of substance use disorders acts primarily to increase the risk for AUD, but not for other substance use disorders. Another study, however, contradicts these findings, suggesting that the level of familial risk is directly proportional to polysubstance use (14). Consequently, it is necessary to clearly establish the nature of the relationship between family factors and polysubstance use in a large sample of current MMT patients.

Family factors may influence polysubstance use amongst individuals with OUD in MMT. However, due to the contradictory nature of the literature, it is unclear whether this is the case. It is important to explore the role of family factors, as an understanding of polysubstance use amongst those with OUD is crucial for the improvement of their treatment outcomes.

2. Objectives

Thus, this study aimed to elucidate the current disparities in the literature by investigating whether an association exists between family factors and illicit polysubstance use amongst individuals with OUD in MMT.

3. Patients and Methods

This study used data collected as part of genetics of opioid addiction (GENOA), a research collaborative between the population genomics program at McMaster University, and Canadian Addiction Treatment Centres (CATC). The detailed methods of GENOA can be found elsewhere (15). Briefly, GENOA is an ongoing prospective cohort study that aims to investigate the relationship between genetic variants and response to MMT amongst patients with OUD. Participants were recruited from CATC sites located in Ontario, which provide treatment for OUD. Information such as treatment details, family history of addiction, and use of other substances was collected using face-to-face interviews and questionnaires, such as the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP) (16). The MAP, as it is used in this study, is an appropriate measure, as its self-reported methadone use has good validity with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.65. The MAP also has excellent test-retest reliability, with an ICC ranging from 0.88 to 0.94 (16). This study has been approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board, and is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) version 4 for cross-sectional studies (17).

3.1. Participants

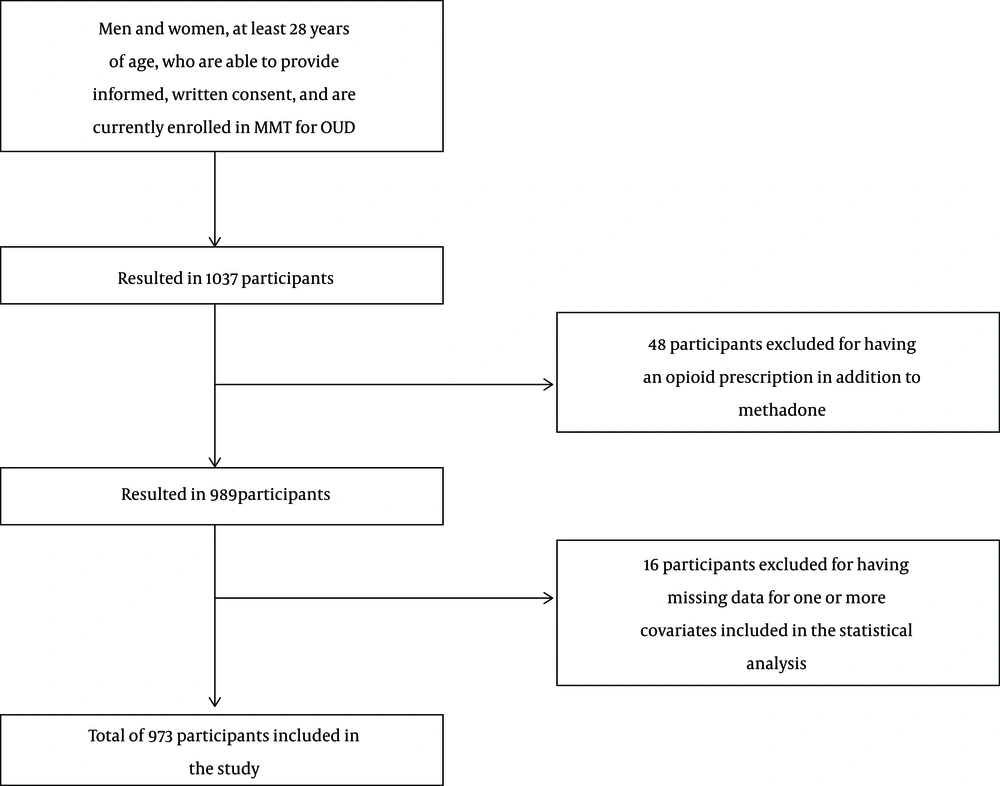

Participants were recruited using consecutive sampling at 17 CATC sites. Inclusion in this study required participants to be at least 18 years of age, and able to provide informed, written consent, in addition to currently being enrolled in MMT for OUD. Participants were excluded if there were English-language barriers. Using these criteria, 1037 participants were eligible for this study (Figure 1). Of the 1037, those currently prescribed an opioid in addition to methadone for other conditions, such as chronic pain, were excluded to ensure that positive urine screens for opioids were a result of illicit use (n = 48). A further 16 participants were excluded due to missing data for one or more covariates included in the statistical analysis, resulting in a final total of 973 participants.

3.2. Measurements

Family history of substance use was measured using a self-report questionnaire. In particular, during interviews, participants were asked, “Is there a history of addiction among your family? If so, who specifically?” Data on the particular substances used by family members were not collected. Using this information, the number of family members with a substance use disorder was recorded as a discrete variable. In cases of participants indicating multiple relatives without specifying a number, such as ‘cousins’, a value of 2 was assigned to capture the minimum number of relatives possible. Meanwhile, the genetic relatedness of those family members was calculated using Wright’s coefficients of relationship (18), and was recorded as a continuous variable between 0 and 100 percent. Illicit opioid use was objectively measured using urinalysis for opioids during the 3 months prior to study intake. Illicit opioid use was recorded as a discrete, binary variable; thus, any number of positive urine screens greater than 0 was considered illicit opioid use. Other substance use was measured using self-report due to the inconsistency amongst CATC sites in urine screening for other substances. During interviews, participants were asked to report their use of substances other than opioids in the past 30 days as part of the Maudsley Addiction Profile. As with opioid use, non-opioid use was recorded as a discrete, binary variable.

3.3. Sample Size

Based on the rule of thumb that we need 10 participants per predictor variable (19), our models are sufficiently stable to test the study hypothesis. Our models include 5 variables (age, sex, length of treatment, amount of current mean methadone dose, number of family members with SUDs, genetic relatedness of family members with SUDs), and thus require at least 50 participants each. Of our sample, 512 participants used opioids illicitly, while 742 used other substances while receiving MMT, safely meeting the 50 participant requirement.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Participant demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. We conducted a multivariable logistic regression to determine the strength of the association between family factors and illicit opioid use. The independent variables were the family factors, specifically the number of family members with SUDs, and the genetic relatedness of those family members to the proband, while the dependent variable was illicit opioid use. The model controlled for age, sex, length of treatment, and amount of current mean methadone dose. A separate, identical analysis was conducted for other substance use, a separate dependent variable, using the same independent variables. The results are reported as odds ratios, corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and p-values. The criterion for statistical significance was set at alpha = 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using RStudio Open Source Edition.

4. Results

4.1. Participants

A total of 973 patients were included in this study (Table 1). Participants’ age varied from 18 to 66 years, with a mean of 38.21 years (standard deviation (SD) = 11.07). Approximately half of the participants were men (53.03%), and 81.50% were of European ethnicity. Most had a high school education or higher (78.21%), with 27.75% having completed some form of post-secondary education, including trade school. However, most of the participants (65.26%) were unemployed. On average, the participants in our study had been in MMT for 51.21 months (SD = 101.36), and their current mean dose of methadone was 73.62 mg/day (SD = 44.81). Participants had a mean of 2 family members with a substance use disorder (SD = 2), with those family members and the probands having a mean genetic relatedness of 30.22% (SD = 20.89).

| Characteristic | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) | 38.21 | 11.07 |

| Current mean methadone dose (mg/day) | 73.62 | 44.81 |

| Length of MMT (Months) | 51.21 | 101.36 |

| Number of family members with SUDs | 2 | 2 |

| Genetic relatedness of family members with SUDs (Percent) | 30.22 | 20.89 |

| N | % of Total (N = 973) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 516 | 53.03 |

| Female | 457 | 46.97 |

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 448 | 46.04 |

| Married/living with a partner | 296 | 30.42 |

| Widowed | 22 | 2.26 |

| Separated/divorced | 201 | 20.66 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| European | 793 | 81.50 |

| Indigenous (North/South/Latin American or Australian) | 71 | 7.30 |

| Other | 94 | 9.66 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| None/grades 1 - 8 | 201 | 20.66 |

| Grades 9 - 12 | 491 | 50.46 |

| Post-secondary and trade school | 270 | 27.75 |

| Employed | ||

| Yes | 338 | 34.74 |

| No | 635 | 65.26 |

| Illicit opioid use | ||

| Yes | 512 | 52.62 |

| No | 461 | 47.38 |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Yes | 407 | 41.83 |

| No | 566 | 58.17 |

| Amphetamine use | ||

| Yes | 34 | 3.49 |

| No | 939 | 96.51 |

| Benzodiazepine use | ||

| Yes | 81 | 8.32 |

| No | 892 | 91.68 |

| Cannabis use | ||

| Yes | 508 | 52.21 |

| No | 465 | 47.79 |

| Cocaine use | ||

| Yes | 221 | 22.71 |

| No | 752 | 77.29 |

| Heroin use | ||

| Yes | 95 | 9.76 |

| No | 878 | 90.24 |

Participant Characteristics (N = 973)

4.2. Illicit Opioid Use

Table 2 presents the results of the multivariable logistic regression for illicit opioid use. Number of family members with an SUD was found to be a significant predictor of illicit opioid use, such that the greater number of family members a patient had with an SUD, the more likely they were to use opioids illicitly while in treatment. An odds ratio of 1.08 (95% CI = 1.01, 1.16; P = 0.03) specifies that this likelihood was an increase of 8% per family member. However, genetic relatedness of family members with an SUD was not significantly associated with illicit opioid use in MMT.

| Outcome | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illicit opioid useb | |||

| Number of family members with SUDs | 1.08 | 1.01, 1.16 | 0.03 |

| Genetic relatedness of family members with SUDs (%) | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.00 | 0.38 |

| Other substance usec | |||

| Number of family members with SUDs | 1.05 | 0.97, 1.15 | 0.24 |

| Genetic relatedness of family members with SUDs (%) | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | 0.41 |

4.3. Other Substance Use

Neither family members with an SUD, nor genetic relatedness of family members with SUDs were significant predictors of other substance use while in treatment. Table 2 displays the full results of the multivariate logistic regression for other substance use.

5. Discussion

The results of this study are the first to suggest that a family history of any substance use acts as a risk factor for illicit opioid use in MMT. These findings highlight a socio-demographic characteristic that healthcare providers should consider when creating treatment plans for individuals with OUD. To ensure that patients are receiving an adequate level of support, it is imperative to understand and respond to the unique risk factors affecting each patient.

Our analyses did not find a significant association between genetic relatedness of family members with a substance use disorder and illicit opioid use in patients with OUD in MMT. However, this study found an association between the number of those family members and illicit opioid use, which suggests a role for familial environmental factors. The findings of this study pertain to adults, while most previous research has investigated youth. Such studies with youth, such as ones that have explored the association between family factors and drug use in young adulthood, lend support for our findings (20, 21). A previous study found that perceived drug use amongst peers and adults during adolescence have a strong effect on problem drug use in adulthood (20). It is possible that, as an adolescent is exposed to an increasingly greater number of family members that use drugs, they are socialized to believe that this substance use is acceptable behaviour. Other research has provided evidence for the role of other familial environmental factors in adolescent drug use, such as poor or inconsistent parenting, economic deprivation, and parental attitudes towards drug use (22).

The fact that our analyses did not find significant associations between family factors and other substance use suggests that the factors linked to opioid and non-opioid use are unique for individuals in MMT. Based on our results, the nature of this relationship is unclear, and should be explored further in future research.

The results of this study also found that 52.6% of our sample used illicit opioids while on MMT, providing an updated general rate of relapse during MMT for the past 3 months.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of our study. First, our sample may be subject to selection bias, as participation in research is voluntary, and it is likely that volunteers may differ from non-volunteers in social and clinical factors. Thus, our sample may not be representative of the population of individuals with OUD in MMT. The representativeness of our sample may be further skewed by the healthy volunteer bias, per which study participants tend to be healthier than the OUD population (23). However, participants for this study were recruited from clinical sites typical of OUD patients receiving MMT. In addition, this study’s findings are not representative of individuals with OUD who are not in treatment.

Furthermore, although we made an effort to adjust for clinically important covariates, our statistical models may have been affected by residual confounding variables. For example, it is possible that the presence of medical or psychiatric comorbidities plays a role in a patient’s illicit polysubstance use (24). However, an attempt to control for some comorbidities was indirectly made, as all participants currently prescribed opioids were excluded from the final analysis. Additionally, our study relied on self-report questionnaires for both measures of family history and other substance use. This presents the potential for reporting bias, as participants may have misremembered information, or may have incomplete information regarding their family history of substance use. Additionally, we were not able to investigate the association between family members’ specific substance use and the proband’s polysubstance use, as data on the types of substances used by family members were not collected. It is likely that the association between family factors and illicit polysubstance use may be unique for each type of substance (13). Finally, due to the presence of some unclear participant responses, the data for number of family members with an addiction may be too conservative. This bias may have resulted in a weaker association, thus understating the strength of the relationship.

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study used rigorous methods to investigate the association between family factors and illicit opioid use in individuals with OUD in MMT using a large sample size. Our results suggest that patients with a family history of substance use are at a higher risk of relapse while in MMT, and may not be adequately supported by the current treatment model. Based on these findings, we suggest that healthcare providers consider stratifying OUD patients based on family history of substance use, and providing additional support to those with a positive family history. Providing family or couples-based therapy has been shown to improve treatment outcomes in MMT, including increasing retention, reducing polysubstance use, and improving social relationships (25). To better identify the nature of the added support necessary for these individuals, future research should explore the effects of specific familial environmental factors, such as socialization, socioeconomic status, and treatment stigma, on illicit opioid use in MMT.