1. Background

Stigma is a special kind of relationship between an attribute and a stereotype, but it is not an essential quality of a person or a thing (1). It is a mark separating individuals from one another based on a socially conferred judgment and causes some persons or groups to be deemed tainted or “less than” others (2). The concept of stigma was initially defined by Erving Goffman in the 1960s, but after decades, it underwent important shifts in definition and characterization (3). In addition to sociological views expressed regarding stigma, there are several definitions of this term in many disciplines such as psychiatry (4), health and medicine (5), religion (6), and culture (7).

Among several forms of stigma, HIV/AIDS-related stigma (H/A stigma) is the worst. This stigma feeds upon, strengthens, and reproduces the existing inequalities in terms of class, race, gender, and sexuality (8). In a review, sociologist Scambler showed that HIV stigma trajectory goes through four phases including at risk (pre-stigma and the worried), diagnosis (confronting an altered identity), latent (living between health and illness), and manifest (passage to social and physical death) (9).

Although H/A stigma is general, women are more vulnerable than men. Campbell called this experience the triple jeopardy impact of H/A on a person infected with HIV, as mother of a child, and carer of the partner, and parents or orphans with AIDS (10). A review conducted by Paudel and Baral showed five themes with regard to this experience, including (1) disclosure, (2) stigma and discrimination, (3) internalized stigma, (4) rejected, shunned, and treated differently by physicians, family, and close friends, and (5) support group as one of the best available interventions for stigma and discrimination (11). A phenomenological study conducted on Cambodian women infected by their husbands showed that their partners became more devoted husbands and agreed to follow safer sex practices within the marriage. However, families suffered from hunger and poverty due to the parents' physical weaknesses (12).

Except families, in other parts of the society sexual relationship is a complex phenomena in Iran (13). HIV/AIDS is closely associated with illegal sexual relationship, which leads to bad experiences of infected women. A study by Mohseni Tabrizi and Hekmatpour showed that negative perceptions, hatred, fear of transmission, lack of knowledge, false beliefs, and healthcare workers’ behaviors formed a kind of HIV stigma that led to mistrust, homelessness, anxiety, hopelessness, desire to die, impotency in marriage, and fear of death in such patients (14). Another study of 15 infected women showed motherhood as a way of stability in life as well as uncertainties about the future. Also, unpleasant experience of pregnancy and delivery was a main theme (15). Fear, shame, rejection by family or friends, and feeling of frustration were other experiences of women recorded by Oskouie et al. (16). Multidimensional stigma, rejection, insult, and discrimination in receiving health services were explored by Saki et al. (17).

Stigma, a culture-based and gender-based concept, can be similarly experienced by most infected people (8, 18), and women are more susceptible to stigma (19). In addition, those infected by their husbands can have different experiences. Specifically, these people are exposed to stigmatization due to the association of AIDS with illegal sexual relationships. In addition, it seems that because of the prevalence of HIV/AIDS, our society will face more cases of these women. However, there is a lack of knowledge based on qualitative studies about psychosocial experiences of these people. Although some studies have been conducted in other countries, there is a lack of such studies in Iran.

2. Objectives

We aimed to explore psychosocial experiences of women infected with HIV by their husbands.

3. Patients and Methods

In 2016, a qualitative content analysis was conducted in Shiraz, Iran. The participants included some women who were infected with HIV by their husbands. These patients were handled in an H/As-dedicated center in Shiraz, Iran, called Lavan center. After making the necessary coordination with the authorities, a list was prepared of women who met the inclusion. The purposive sampling technique was used to identify a wide range of participants. One of the directors in the center contacted the eligible patients by phone and explained to them the research objectives. Then, a time was set for interviews with those who volunteered to participate in the study. About five people refused to participate mostly due to stigma and confidentiality issues.

We collected data through focus group discussions (FGDs). Based on the saturation criteria, two FGDs were conducted with two groups of five. The groups were selected based on purposive sampling and accessibility. The discussions took place in an official hall of the center. An MSc researcher who was familiar with qualitative studies and FGDs guided these discussions as a leader. In addition, the coordinator of the center helped her with the discussions. After a verbal consent was taken from the focus group in each discussion, the goal of the study was presented again to the participants. Then, the main question was discussed as “Please explain to us as a woman who has been infected with HIV by her man what experiences you have ever had with HIV’’. Based on the responses of the participants, subsequent questions were asked related to the subject. The discussions were managed and controlled by the leader. They were finished when the responses were repetitive and did not add any new information. Data were recorded digitally. At the end of the discussions, a sum of 15,000 Tomans (about 5 USD at the time) was paid to each participant.

Data analysis was performed with the conventional content analysis technique. Hsieh and Shannon defined three approaches for qualitative content analysis. In conventional content analysis, categories are derived directly from the text data (20). For this reason, the concepts were derived from the data inductively (21). Categories were explored with merging concepts and sub-categories. In this process, researchers went over the data several times to ensure they had performed a thorough analysis.

Transcription, as the first step in a qualitative data analysis (22), was performed completely. Afterwards, data analysis was conducted using the qualitative content analysis technique. Conventional, directed, and summative approaches are the three main approaches of content analysis (20). In this study, we used the conventional approach. Two researchers coded the data separately. Thus, categories were derived directly from the text data inductively without any theoretical view. Defining the unit of analysis, developing the categories, and making a coding scheme were performed during inductive coding. Themes were explored by adding another level of hierarchy to the “code tree”. For this purpose, each similar unit of meaning was defined as a new sub-theme. Many content sub-themes were defined as a theme.

Basically, trust is a main factor in qualitative research. From Guba’s viewpoint, it includes (a) credibility (in preference to internal validity), (b) transferability (in preference to external validity/generalizability), (c) dependability (in preference to reliability), and (d) confirmability (23). In this study, validity, reliability, and objectivity were the criteria used to evaluate the research quality. Credibility was established through participant observation and member checking. For transferability, explicit connections were made to the cultural and social contexts in which data collection was performed. For dependability, a researcher outside the data collection and data analysis examined the data collection and data analysis processes as well as the results of the research and confirmed them. Audit trial and reflexivity analysis were performed for conformability of the study.

3.1. Research Ethics

The participants made their contribution with consent and free will. The information derived from them was maintained confidential throughout the research. The present study also observed the codes of the Declaration of Helsinki (19) and those of the American Sociological Association (20). Based on these considerations and research ethics, names of all participants in this study were kept confidential. Privacy of the participants was also taken into consideration.

4. Results

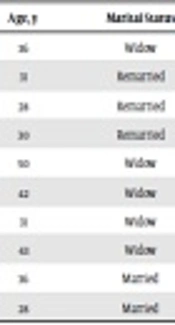

Ten participants contributed to this study. The age range of the patients was 28 - 50 years, and their mean age was 34.81 years (Table 1).

| ID | Age, y | Marital Status | Time of Having HIV/AIDS, y | Number of Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | Widow | 8 | 1 |

| 2 | 31 | Remarried | 5 | 1 |

| 3 | 28 | Remarried | 9 | 1 |

| 4 | 30 | Remarried | 8 | 1 |

| 5 | 50 | Widow | 8 | 5 |

| 6 | 42 | Widow | 9 | 2 |

| 7 | 31 | Widow | 6 | 0 |

| 8 | 43 | Widow | 4 | 2 |

| 9 | 36 | Married | Unknown | 2 |

| 10 | 28 | Married | 3 | Pregnant |

Characteristics of the Participants

Data analysis yielded 147 meaning units, 25 concepts, 14 sub-themes, and 4 themes. Experience of stigma was very difficult for the all participants. Three of them were crying during FGDs (Focus Group Discussions), which was very deplorable. None except one person used the term HIV or AIDS. They just called it “this illness”, which could be due to a type of continued fear of the disease. Content analysis of the statements showed that stigma and discrimination were the main problems for these people, which had led to their marginalization. Indeed, the stigma of H/A is so severe that such people have to hide it in various situations. Except parents and partners, other people are not willing to accept them. However, what troubled the participants the most was the label of harlotry in the public. They were exposed to this charge because H/A is generally believed to be transmitted through underground sexual relations, though these people were infected by their husbands. This situation had led to severe psychological problems. Generally, four concepts could be extracted from the participants’ statements, including onomatophobia, social stigma, discrimination, and self-stigma.

4.1. Onomatophobia

All the participants experienced onomatophobia. The term H/A is equal to a psychosocial pressure on patients. Among those who participated in the study, just participant 7 used the term HIV+. Several uses of ‘this illness’ by the other participants showed that they were afraid of exposure to the term. This is often due to the social reactions to the term H/A, which is associated with illegitimate sexual relations. The participants believed that they were all infected by their husbands, but they were labeled with harlotry. They tried a low and hidden voice to say ‘I did not have any illegitimate sexual relations; I am a chaste woman’. They felt people were suspicious of them. However, it was just their families who accepted their innocence. Over time, this had caused a phobia in the subconscious minds of the participants about the name of the disease. Participant 8 said that she had gone to Lavan center secretly because if anyone knew she was there, he or she would think she was a dirty woman or a sex worker. The other participants had a similar experience. The following quotation is noteworthy:

“I die of fear when I hear the name of the disease. I sit at a corner and pray. In the hospital, I fear when a nurse mentions the disease and tells me I have it” (participant no.5).

The name of this disease creates stress for participants. They even suffered from hearing the name through the media.

“When the TV mentions its name I'm afraid, I say turn it off. Even when I come here to get medicine I'm crying like a rainstorm, I'm scared of its name” (participants no 6).

Although both AIDS and HIV terms induced bad psychological effects, AIDS was worse. For example, participant no.7 said:

“I hate the word “AIDS” very much, so I say everywhere HIV. Someone told me you’re having a very hard time. I better accept HIV than AIDS. I say to myself, the last stage is AIDS. I am self-deceived. Escape from this word. Why lie I miss this word”.

4.2. Social Stigma

The general attitude of social dishonor against the disease has improperly created an attitude of shame, scandal, and disgrace. All patients experience marginalization due to stereotypes against this disease. This leads to social insecurity, which may prevent HIV patients from disclosing their conditions to others and serve as a barrier to public approval. Also, people step away from these patients, specifically for the fear of probable transmissibility of the disease. In other words, because of the social threats of the disease, H/A-infected people are avoided. The participants believed that people of the society, even hospital staff, would take a distance from them once the disease is pronounced. Thus, apart from harlotry labeling, transmission of the disease seems to be a major problem as well. The following statement indicates how such diseased people are avoided by the society and even their relatives:

“After my relatives learned that I had AIDS, none of them associated with me. After they discovered that it is not transmitted easily, some of them resumed their relationships. However, some still do not come over to my home” (participant no.7).

Participant no.5 had a similar experience about her close relatives:

“All people have left me, even my daughter-in-law. No one looks at me except my sisters or sometimes my sons. I do not count on anyone except God”.

Statements of participant no.7 also showed that social stigma threatens her children.

“Why people disconnect with you when they know the problem? Someone understood my problem, she even avoided my children”.

Gender reinforces the social stigma. In other words, having HIV/AIDS was worse for these participants because they were female.

“It is really hard for a woman. When someone knows you have HIV they ask ‘did you have a husband’? I get very annoyed. Despite they know I got it from your husband, they look at me as an evil” (participant no.3).

4.3. Discrimination

Because of social stigma, women with H/A are deprived of social rights. There are manifest discriminations that lead to the isolation of these women. Also, the social stigma and the harlotry label cause them not to tend to have an active interaction in the society. They think that if their problem is disclosed, they are bypassed severely by the society. Inappropriate behavior towards these people, as a segregated class, is common. In this case, social stigma is a sufficient reason for violating the rights of these people. In the present study, the participants tried to escape social discriminations by hiding their diagnosed disease, specifically in health sectors. Seven participants had experienced discrimination in health sectors. Just Lavan center had accepted them, and it seems if the other four participants had gone to other health sectors they would have faced with discrimination. According to what they stated, they had the worst experience of discrimination by healthcare providers in clinics and hospitals:

“I went to a gynecology clinic. When the physician learned about my problem, she did not check me. She said, “you have AIDS” and rejected me despite the fact I had a letter of introduction from Lavan center” (participant no.7).

The most discrimination happened in the health sector because these people can hide their problem in other parts of the society. However, they were trained that they should inform their healthcare team about their disease. In addition, most of the time they referred to health sector because of their main problem (HIV/AIDS). Therefore, most of the discrimination was experienced in the health sector.

“Once I went to a clinic. When the doctor understood I have HIV, she pushed her chair back and said do not move. I was so annoyed” (participant no.1).

4.4. Self-Stigma

Due to the problems mentioned above and such problems as divorce, death of husband, being alone, and feeling of guilt, the women were faced with a problem called ‘self-stigma’. Five participants had experienced this stigma. This stigma is related to the relationship of affected people with themselves, their soul, their body, and their potentials, which leads to negative feelings toward themselves. These negative feelings include shame and whining, hopelessness, self-blame, self-deprivation, low self-esteem, depression, suicidal thoughts, marital refusal, and other related emotions.

Because the disease was transmitted through sexual relation with their husbands, they have bitter experiences regarding sexual intercourse. They have no interest in establishing relations or do not gain satisfaction in their sexual relationship. This is why they often refuse it. As for widows, they refuse to get married again. Some of them are affected by chronic depression and cannot wait for death, and some others start contemplating suicide. In the event of self-stigma, an afflicted woman’s main problem is her relationship with her family, specifically her children. As it was found in this study, such women are worried about the potential infection of their children. In other words, a type of compelling obsession dominates them. This leads to the limitation in their relationship with their children, which exacerbates their feeling of shame and guilt. This is a problematic situation that results in severe hopelessness. The following statement is quite suggestive of lack of hope:

“My children do not know about my problem. I do not hug them so that they might not take my disease. My son complains to my mother in that I don’t hug him and that I am obsessed. At eating time, I try hard not to leave any food in my dish or take care our food is not mixed up. My problem is that death does not come. I believe the sooner I die, the more comfortable I will be” (participant no.6).

These people were alone. They prayed sometimes as follows:

“Sometimes I ask God why I got caught up? What was my sin? Oh my God, what is this misery” (participant no. 8).

Disappointment was clear in the statements of some participants, specifically those who did not have anyone and lived alone. These people did not have any hope for their lives and future.

“I'm just alive, and I have no hope” (participant no.5).

5. Discussion

H/A stigma is the worst type of stigma. The act of crying by some participants during FGDs showed the tragic condition of these patients. This problem is related even to the name of the disease. Onomatophobia, social stigma, discrimination and self-stigma were the general experiences of the participants. The first three features are associated with social problems, while the last one is psychological and mostly due to social problems. Self-stigma was so severe that those people did not have any hope and were living with continued psychosocial pressures.

It seems that they were experiencing a dark and dangerous society that excluded them from the natural processes of their social life. The society, indeed, had marginalized them severely. The term H/A is mysterious, like devil, and the infected do their best to keep it a secret. Disclosure of this secret may lead to removing them from any social position. Thus, such people have to carry it as an encrypted evil which, if disclosed, will mean social exclusion. This affects their state of mind, social relationships, and welfare.

The results of this study were in line with those of the study by Darlington and Hutsons, who hypothesized that AIDS social stigma plays a significant role in the psychosocial behaviors and well-being of women, especially those who live in traditional conservative areas (24). Also, Brondani et al. showed that despite advances in HIV diagnosis, treatment, and education, stigma continues to disproportionately affect the health outcomes of people living with H/A (25). Beginnings of stigma, tensions related to disclosure, experiences of service seeking, and what occurs beyond HIV stigma and discrimination were presented in a study by Donnelly et al. Fear has been found as the main cause of inaccessibility of these people to care (26). Our findings are in agreement with those of the above studies.

Stigma and fear of diagnostic disclosure were also the findings of other studies. Arrey et al. conducted a study under the title “It’s My Secret” and showed that sub-Saharan African migrant women usually disclosed their situation only to healthcare professionals because of the treatment and care they need (27). The study of Colombini et al. had similar findings as to the relationship of these women with their partners (28). Multi-dimensional stigma, rejection, insults, and discrimination in providing health services were detected by Saki et al. (17). Similarly, in the case of our participants, an important problem was discrimination in the health sector. Generally, health care providers had shown severe discrimination against our participants. Other studies in Iran have shown that doctors and nurses involved with HIV patients treat them with insults, humiliation, negligence, and lack of response (14).

Generally, our findings were in concord with the results of Paudel and Baral who showed disclosure, stigma, discrimination, internalized stigma, rejection, pretention, and being treated differently by physicians, family and close friends (11). However, family was found as the main support of the patients. In this case, parents and husbands play a pivotal role in promoting hope in the patients.

Dos Santos et al. showed that stigma and discrimination negatively impact the health as well as working and family life of infected women and their access to health services (29). Also, stigma delays seeking medical treatment and access to treatment, which undermine their identity and capacity to cope with the disease, limit the possibility of disclosure of the disease even to potential sources of support such as family and friends, and lower the possibility of using certain safer sexual practices (30). Thus, stigma creates significant barriers to HIV prevention, testing, and care and can become internalized in people living with HIV/AIDS (31).

Although our study was in agreement with several other studies about stigma and discrimination, it has explored a different dimension of stigma known as onomatophobia, which is related to harlotry labels. This phobia is actually the cultural side of a stigma (8, 18), where the afflicted ones are seen as prostitutes. No need to say that it is a painful charge. Because of the religious context of the society and due to the close ties between infection and illegitimate sexual relations, these people experience this type of stigma. In such a context, a person can be easily exposed to charges because being HIV-positive means she has had illegal sexual relations or is a prostitute. Although we do not know how many of such people exist, it is quite unfair for them to be socially treated with charges. They try to prove their innocence but they cannot succeed.

Theoretically, it can be stated that stigma is a global phenomenon. Tyler and McWade believed that stigma is rooted in the doctrine of neoliberalism, which operates not only by capitalizing upon ‘shocks’, but also through the creation and mediation of stigma (32). Here, the medical system stands in a paradoxical condition. While medical practitioners claim to have reduced discrimination, this study shows that the main cause of psychosocial pressures is the medical system. A medical system is, indeed, the flagship of stigmatization of H/A by its domination in the culture of a society. The results showed that, in this context, the medical system not only makes the social stigma but it strengthens stigma and discrimination against H/A people. In addition, it seems that stigma and discrimination tend to be more feminine than masculine. In other words, women are more vulnerable to stigma than men. This is due to the masculine structure of the society. Also, as a dominant paradigm, much of the literature on HIV prevention portrays women as especially vulnerable to HIV infection because of their biological susceptibility, while men are portrayed with sexual power and privilege (33).

Finally, an important point is that if discriminations are allowed to continue in the health sector, they will soon turn into a prevalent problem. That is why healthcare policymakers are strongly advised to pay due attention to this major issue. As Stuber et al. believe, this is a great urgency to understand this problem and to aid in the development of effective public health strategies (34). Designing effective programs and interventions needs a thorough understanding of stigma and discrimination (8). It is suggested that health policies delineate a clear process for legal pursuit of any discrimination against H/A people.

5.1. Conclusion

In nearly every society, H/A is commonly associated with stigma. However, experience of stigma is culture-dependent. This study showed that women infected by their husbands have to remain silent about their disease or talk about that in a low voice, as in “I have a secret about myself that no one should know. I’m a chaste woman, not a prostitute”. This feeling of stigma and the likely label of prostitution as well as the social discrimination that follows make these people sensitive to the term H/A. It exposes them to severe psychosocial pressures, making them hide their diagnosed disease. In addition to this social stigma, self-stigma is another experience of these people. They feel guilty and hopeless and pose limitations to themselves in their relationship with their children. Based on the findings of our study, supporting such people seems to be a social responsibility of our policy makers. Reduction of discrimination in health sectors alongside psychological and social work consultation is suggested for these patients.

5.2. Limitations

Women with H/A experience stigmatization. Despite these people are infected because of legitimate sexual relationships, they are stigmatized badly. The results showed that these patients are marginalized and are faced with several problems. Therefore, policymakers should consider two kinds of women with H/A problems. Providing psychological consultation for these people is inevitable. In addition, policymakers should consider solving social pressures of marginalization by using mass media and context of schools and universities. Other qualitative studies with larger sample sizes is recommended. As this was a qualitative study, our findings should be extrapolated with cautious, thus, other quantitative studies are suggested.