1. Background

Biofilm is characterized by closely arranged cells inside a matrix or gel-like material produced by cells themselves. Biofilms are highly resistant to some environmental conditions where the same normal free-living bacteria are readily killed (1-4). Bacteria can attached to all surfaces of the human body, including skin, teeth, and gut, and when the attachment is irreversible, biofilm formation initiates (5-7). Several pathogenic bacteria are biofilm producers, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Streptococcus mutans, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenza, Burkholderia cepacia, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (1-4).

The communal lifestyle of biofilm members is often much different than the single bacterial cells (8). Generally, bacterial cells at the stationery growth phase produce biofilms when the environmental conditions become harsh for planktonic cells due to nutrient depletion or toxic substance accumulation (9). Biofilm formation is a step-by-step process of attachment, maturation, and dispersion. In addition to the help of flagella and fimbriae, Van der Waals forces between cells and the surface play an important role during adhesion. Adhesion can be both reversible and irreversible (10, 11). After the first successful attachment of cells to a surface, they produce more and more matrix products like extracellular polysaccharides or intracellular polysaccharides (e.g., glucose, mannose, galactose, N-acetyl-glucosamine, galacturonic acid, arabinose, fucose, rhamnose, and xylose) (12). These polysaccharides provide scaffolding to make it possible for carbohydrates, proteins (help in biofilms architecture and structural strength), lipids, and nucleic acids to attach (7).

The physical structure of matured biofilms can resemble mushroom from outside (13). There are channels to provide air, nutrition, and water for the cells (7). Biofilm inhibits the easy access of antibacterial agents, and high concentration of cells inside it facilitates gene transfer mechanisms (14). As the biofilm grows, population outgrowth creates competition for nutrients; the dispersal step initiates where the outermost cells leave the biofilm as planktonic cells again and start new biofilms in another site (1, 4, 15).

Wound infection with biofilm producers is difficult to eradicate as the antibiotic treatment often used to kill planktonic cells fails to kill the bacteria in biofilms (16, 17). Several mechanisms can be responsible for such resistance, such as limited access of antibiotics to the biofilm interior, activation of efflux pump mechanism, slowed down growth rate, formation of persister cells, production of enzymes capable of degrading antimicrobial agents, charged extracellular polysaccharides binding to antibiotics and inhibiting entering cells from the matrix, etc. (2, 4, 18, 19). Wounds infected with biofilm producers like Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have been reported in numerous studies (20-23).

2. Objectives

The aim of the study was to identify the bacteria in infected wounds and determine the biofilm production capability of these bacteria. Simultaneously, the antibiotic resistance of these bacteria before and after biofilm formation was evaluated to determine changes in resistance pattern.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Collection and Study Area

After asking for patients’ permission in a local healthcare center in Dhaka, Bangladesh, during September, 2019, wound samples from outpatients were collected using sterile cotton swabs following the Levine technique (24). The samples were collected aseptically and sent to a laboratory immediately for microbiological analysis.

3.2. Identification of Bacteria

Streaking was performed from the swabs on culture media plates. Two types of agar plates were used to isolate the pathogens. One was MacConkey agar, and the other was blood agar. After 24 hours of incubation, growth was observed, and the isolates were then subjected to the biochemical identification process. Triple sugar iron agar test (TSI), catalase, oxidase, citrate utilization, methyl red (MR), Voges-Proskauer (VP), and indole test were performed as the biochemical tests.

3.3. Determination of Protease Activity

Protease enzyme production capability was determined by streaking the bacterial isolates on casein agar plates and gelatin deep tubes. Casein plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours for observation of clear zone around bacterial colony. Gelatin deep tubes were observed every 24 hours for seven days. During each observation, tubes were refrigerated at 4°C to detect non-solidified portion (due to proteolysis).

3.4. Biofilm Production by the Congo Red Agar Method

Congo red agar was used for the biofilm production of wound bacteria. The plates were inoculated with the bacteria by the streak plate technique and incubated for 24 to 48 hours at 37°C. Black colonies indicate biofilm formation (25).

3.5. Determination of Antimicrobial Susceptibility of the Isolates

Isolates collected from the wound samples were tested for antibiotic susceptibility before and after biofilm formation on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco, Detroit, MI) by the Kirby-Bauer method with Vancomycin (30 µg), Neomycin (30 µg), Cotrimoxazol (30 µg), Ceftazidime (40 µg), Nalidixic Acid (30 µg), Chlortetracycline (30 µg), Novobiocin(30 µg), Linezolid(30 µg), Ciprofloxacin (5 µg), and Azithromycin (15 µg). After 24 hours of incubation, the plates were observed for inhibition zones, and the findings were interpreted as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant (26).

4. Results

After biochemical identification, we found Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Proteus mirabilis, Proteus vulgaris, Corynebacterium xerosis., Alcaligenes faecalis, Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus spp., Shigella spp., and Salmonella spp. (Table 1) in 20 wound samples, among which Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhimurium, Corynebacterium xerosis, and Alcaligenes faecalis showed protease activity (Table 2).

| Isolate No. | TSI | Citrate | Indole | Catalase | Oxidase | MR | VP | Identified Bacteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slant | Butt | Gas | H2S | ||||||||

| 01 | A | A | + | - | |||||||

| 02 | A | A | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | Acinetobacter spp. |

| 03 | K | A | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | Proteus mirabilis |

| 04 | K | A | - | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | Proteus vulgaris |

| 05 | K | A | - | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | Proteus vulgaris |

| 06 | K | A | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | Proteus mirabilis |

| 07 | A | A | - | - | - | - | + | + | - | - | Alcaligenes faecalis |

| 08 | K | A | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | Salmonella spp. |

| 09 | K | A | - | + | + | - | + | - | - | + | Salmonella spp. |

| 10 | A | A | - | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| 11 | A | A | - | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | Corynebacterium xerosis |

| 12 | A | A | - | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| 13 | A | A | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | - | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 14 | K | A | - | - | + | + | + | + | - | + | Bacillus cereus |

| 15 | A | A | + | - | + | - | + | - | + | + | Staphylococcus aureus |

| 16 | A | A | + | - | - | + | - | - | + | - | Escherichia coli |

| 17 | K | A | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | Corynebacterium xerosis |

| 18 | A | A | - | - | - | - | + | - | + | + | Staphylococcus spp. |

| 19 | K | K | - | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| 20 | K | K | - | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

Abbreviations: A: Acidic, K:Alkaline

| Isolate No. | Bacterial Isolate | Casein Hydrolysis | Gelatin Hydrolysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Escherichia coli | - | - |

| 02 | Acinetobacter spp. | - | - |

| 03 | Proteus mirabilis | - | - |

| 04 | Proteus vulgaris | - | - |

| 05 | Proteus vulgaris | - | - |

| 06 | Proteus mirabilis | - | - |

| 07 | Alcaligenes faecalis | - | + |

| 08 | Salmonella spp. | - | + |

| 09 | Salmonella spp. | - | - |

| 10 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | - | - |

| 11 | Corynebacterium xerosis | - | - |

| 12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | - | - |

| 13 | Staphylococcus aureus | - | - |

| 14 | Bacillus cereus | - | - |

| 15 | Staphylococcus aureus | - | - |

| 16 | Escherichia coli | - | - |

| 17 | Corynebacterium xerosis | - | + |

| 18 | Staphylococcus spp. | - | - |

| 19 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | - | - |

| 20 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | - | + |

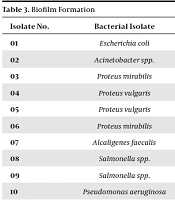

Among the 20 isolates, 10 (isolates 01, 03, 04, 08, 09, 11, 12, 13, 16 and 20) were biofilm producers (Table 3). Escherichia coli showed resistance to vancomycin, nalidixic acid, and chlortetracycline, while it was susceptible to these drugs before biofilm formation (Tables 3 and 4). In addition, Proteus vulgaris spp. showed resistance to linezolid and Proteus mirabilis to chlortetracycline after biofilm formation.

| Isolate No. | Bacterial Isolate | Biofilm Production |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | Escherichia coli | Positive |

| 02 | Acinetobacter spp. | - |

| 03 | Proteus mirabilis | Positive |

| 04 | Proteus vulgaris | Positive |

| 05 | Proteus vulgaris | - |

| 06 | Proteus mirabilis | - |

| 07 | Alcaligenes faecalis | - |

| 08 | Salmonella spp. | Positive |

| 09 | Salmonella spp. | Positive |

| 10 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | - |

| 11 | Corynebacterium xerosis | Positive |

| 12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Positive |

| 13 | Staphylococcus aureus | Positive |

| 14 | Bacillus cereus | - |

| 15 | Staphylococcus aureus | - |

| 16 | Escherichia coli | Positive |

| 17 | Corynebacterium xerosis | - |

| 18 | Staphylococcus spp. | - |

| 19 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | - |

| 20 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Positive |

| Isolate No. | Bacterial Isolate | Vancomycin (30 µg) | Neomycin (30 µg) | Cotrimoxazol (30 µg) | Ceftazidime (40 µg) | Nalidixic Acid (30 µg) | Chlortetracycline (30 µg) | Novobiocin (30 µg) | Linezolid (30 µg) | Ciprofloxacin (5 µg) | Azithromycin (15 µg) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | ||

| 01 | Escherichia coli | 10 | - | 17 | 11 | 28 | 28 | - | - | 24 | - | 15 | - | 29 | - | - | - | 10 | 10 | 22 | 16 |

| 03 | Proteus mirabilis | - | - | 19 | 15 | - | - | - | - | 27 | 28 | - | 10 | 10 | - | - | 39 | 22 | 29 | 23 | |

| 04 | Proteus vulgaris | 10 | - | 18 | 12 | 30 | 25 | 32 | 13 | - | - | 32 | 21 | - | - | 12 | - | 10 | 10 | 31 | 26 |

| 08 | Salmonella spp. | 14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15 | 10 | 30 | 21 | |

| 09 | Salmonella spp. | - | - | 23 | 10 | - | - | 14 | - | 20 | 12 | - | - | 11 | - | - | 25 | 13 | 25 | 13 | |

| 11 | Corynebacterium xerosis | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | - | 13 | - | 15 | - | - | - |

| 12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 10 | - | 10 | - | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16 | - | - | - | 19 | - | - | - |

| 13 | Staphylococcus aureus | - | - | - | - | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21 | 12 | 12 | - |

| 16 | Escherichia coli | 12 | - | 15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | 14 | 30 | 15 |

| 20 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 10 | - | 18 | - | 17 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | - | 31 | 15 | 29 | 20 |

5. Discussion

Twenty wound samples were subjected to biochemical identification, and after the biochemical tests, we found Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Acinetobacter spp., Proteus vulgaris, Alcaligenes faecalis, Salmonella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Corynebacterium xerosis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Bacillus cereus (Table 1). Simultaneously, the bacteria’s extracellular protease activity was also examined. None of the isolates from the 20 samples showed casein hydrolysis activity, but a few were proved to be capable of hydrolyzing gelatin (Table 2). They were samples no. 7 (Alcaligenes faecalis), 8 (Salmonella spp.), 17 (Corynebacterium xerosis), and 20 (Pseudomonas aeruginosa).

Gelatin hydrolysis occurs with the help of the gelatinase enzyme, which contributes to the virulence of wound bacteria. This helps bacteria to escape from the wound and disseminate to the distal body parts and cause diseases like endocarditis (27, 28). Bacteria with gelatinase production capability can spread to the internal organs passing the connective tissue if antibiotic treatment does not reach into the biofilm. About 10 isolates (50% isolates) were biofilm producers (Table 3), indicating a great threat for treatment as antibiotics might not reach the biofilm interior due to the antibiotic reflux mechanism.

Antibiotic sensitivity was evaluated both before and after biofilm production (Tables 4 and 5), and it was revealed that most isolates that were sensitive before biofilm formation became resistant (Table 4). Some isolates with a large inhibition zone showed a quite small inhibition zone, indicating the decreased capacity of antibiotics to inhibit the growth of microbes after biofilm formation. For instance, Pseudomonas aeruginosa with a 31-mm zone for ciprofloxacin showed a 15-mm zone after biofilm formation, which is nearly half of the original size. Only few bacteria showed no changes in antibiotic resistance within 24 hours (e.g., Escherichia coli for ciprofloxacin and Proteus mirabilis for novobiocin).

| Isolate No. | Bacterial isolate | Vancomycin (30 µg) | Neomycin (30 µg) | Cotrimoxazol (30 µg) | Ceftazidime (40 µg) | Nalidixic Acid (30 µg) | Amoxycillin (25 µg) | Chlortetracycline (30 µg) | Novobiocin (30 µg) | Linezolid (30 µg) | Cefuroxime (30 µg) | Ciprofloxacin (5 µg) | Azithromycin (15 µg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Escherichia coli | 10 | 17 | 28 | - | 24 | - | 15 | 29 | - | - | 10 | 22 |

| 02 | Acinetobacter spp. | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14 | - | - | - | 16 |

| 03 | Proteus mirabilis | - | 19 | - | - | 27 | - | - | 10 | - | - | 39 | 29 |

| 04 | Proteus vulgaris | 10 | 18 | 30 | 32 | - | - | 32 | - | 12 | - | 10 | 31 |

| 05 | Proteus vulgaris | 10 | 20 | - | - | - | - | 23 | 11 | - | - | - | - |

| 06 | Proteus mirabilis | 12 | 12 | 18 | - | - | - | - | 13 | - | - | - | 10 |

| 07 | Alcaligenes faecalis | - | - | 30 | - | - | - | - | 16 | - | - | 10 | 26 |

| 08 | Salmonella spp. | 14 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15 | 30 |

| 09 | Salmonella spp. | - | 23 | - | 14 | 20 | - | - | 11 | - | - | 25 | 25 |

| 10 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | - | 15 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | - | - | 10 | - |

| 11 | Corynebacterium xerosis | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | - | - | 19 | - |

| 12 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 10 | 10 | 11 | - | - | - | - | 16 | - | - | - | - |

| 13 | Staphylococcus aureus | - | - | 12 | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | - | 21 | 12 |

| 14 | Bacillus cereus | 14 | 25 | 29 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 18 | 15 |

| 15 | Staphylococcus aureus | 10 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - | 9 | - | - | - | - |

| 16 | Escherichia coli | 12 | 15 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 20 | 30 |

| 17 | Corynebacterium xerosis | - | 24 | 30 | 11 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | Staphylococcus spp. | 9 | 15 | 23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 21 |

| 19 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 12 | 10 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 15 |

| 20 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 10 | 18 | 17 | - | - | - | - | - | 11 | - | 31 | 29 |

As it is difficult to treat biofilms with antibacterial agents, the first priority would be to prevent the formation of biofilms before their development (29). This study aimed to determine biofilm-producing bacteria isolated from wound samples. Based on our findings, it is imperative to take measures to stop bacterial growth in wound sites. Due to the open wound, the primary immune barrier is already broken down, and the leaking plasma provides an optimal environment with nutrient supply for bacteria to grow further and produce biofilms. Thus, regular sterilizing of the wound site with an appropriate proportion/concentration of antibacterial agents is key to prevent bacterial growth. Also, the antibiotics regimen should be adhered to according to the prescription, and there is no alternative to strictly following the physician advice.

5.1. Conclusions

Bacteria causing wound infection can produce biofilms very easily if left untreated or unclean. As it is difficult to inhibit bacteria after biofilm formation with antibiotics or organic substances, which can usually stop wound infection, strict care must be given to sanitize the wound site properly to prevent any infection.