1. Background

The tuberculosis (TB) disease is still among world’s leading infectious diseases (1). Although accessible antimicrobial agents are effective at eradicating infections, there are issues with emergence of drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains (2). Additionally, increased incidence of HIV infection has been shown to be associated with an increased mortality rate (3).

Some plants have been proven to be the sources of useful drugs. Cinnamaldehyde (Figure 1) has been elicited from several plants, such as Cinnamomum cassia. The cinnamaldehyde has been used in traditional medicine and has been demonstrated to suppress the growth of Clostridium botulinum (4), and Staphylococcus aureus (5). A few studies have reported on mechanisms underlying the effects of antimycobacterial agents (6).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine antimycobacterial effects of cinnamaldehyde.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Bacterial Strains and Reagents

The cinnamaldehyde was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich chemical company. Mycobacterium tuberculosis was obtained from Zabol University of Medical Sciences.

3.2. Growth Curve of Mycobacterium tuberculosis With Different Concentrations of the Cinnamaldehyde

Mycobacterium tuberculosis was grown in a flask (100 mL) containing the Middlebrook 7H9 medium. Then, 1 mL of culture was placed in each of tubes and exposed to different concentrations of the cinnamaldehyde.

3.3. Cell Culture and Treatment by Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis was grown in the Middlebrook 7H9 broth. The drug treatments were carried out by adding stock solution to one of the cultures.

3.4. Quantification of Gene Expression by Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Real-time PCR reactions were carried out using a Rotor-Gene 6000. Primers used are shown in Table 1. Analyses were carried out using the relative expression software tool (RESTª) software as described by Pfaffl et al. (7).

| Gene Name | Sense Primer | Antisense Primer |

|---|---|---|

| frdA | ACGAGCACAACAAAGGTACGA | AGGTGCAGCAGGTCTAGATTGA |

| frdB | CTTGAATCTCGGTGAAAGAC | ACCGATTTGACCAGATCATC |

| frdC | AGGAGATGCTGACTGAGAT | CTAGCGCCTCATTAAGATT |

| frdD | GCAACCCGATCACCAAGCTAGAT | CATGGTCGAGCACGAACCGCATC |

| narJ | CACCCACTACGCCAATATCT | AGCGGTACCACACTGACAC |

| narI | GAGTCCTCGTCGGAGATATG | GAACCCGAGGTGAATATATC |

| narH | GTTTGTGGGTTGACTATG | CGGTTTGCCATACATTGAAG |

| narG | GCTAGTGATCGAACACAA | CAACCCCAAGTACAACA |

| pks3 | TCCACACTCGCTACTAATAG | TATCCACCAGTACAGCACAT |

| papA3 | CTTTGAGGTTGTCGCGACAC | CGACGAACACCAGCATAAT |

| Mmpl10 | ACTCGGCGTATATCTGAAGG | CTGTCCATACGGGTCAAAGT |

| rpsH | GAGCGTCAAGTCAGTATAGA | CAACTGATAGGTGGCGTCGT |

| rpsS | CAAGGCTAAAACTCACACGA | GGACTTAACCCAACATATAA |

| rplW | CTGCATCTGCGACTAAGTA | TCGATGGACAAGGTGTAGAA |

| rplT | ACCTTCGAGGACCTGAAATT | CCTCCACCACAACTACGTAT |

| rplO | GCAAGACAAGTGCTGATCAA | GAAGCGCTCAAAGAAACAAC |

| rplD | GTGGACGGCGATTGAAAATT | AGCTGGCTGGGTGAACGC |

| rplB | GGTAGCCAGCAAATAATACT | GCCAAGATGGTGTAGAGAAT |

| infC | AGACCGTCGTCATAGAACAATAG | TTGGTCTCGTAATCGAGATAGT |

| rho | AGGTCATCCAGCAGTATATG | TTGGTCACCGAAATAGAAGA |

| argR | GGTGTTTGTGTTGTCAATAC | TAGCGCATCAGGATGAACAA |

| argJ | GGATGACCTGCATAAGCAAT | GAAGCGCTCAAAGATACGTC |

| argG | CCAAATGGCCAGATATCAAC | CGAGCACCTGTTGTTAGTG |

| argF | CTACCACCGCCGTCTATATA | CCCTCTTCCACTGACATGAT |

| argD | GCGATGTATCAGTCAGTAAG | GCATTGGCGACTACAATG |

Primers Used in the Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Studies

4. Results

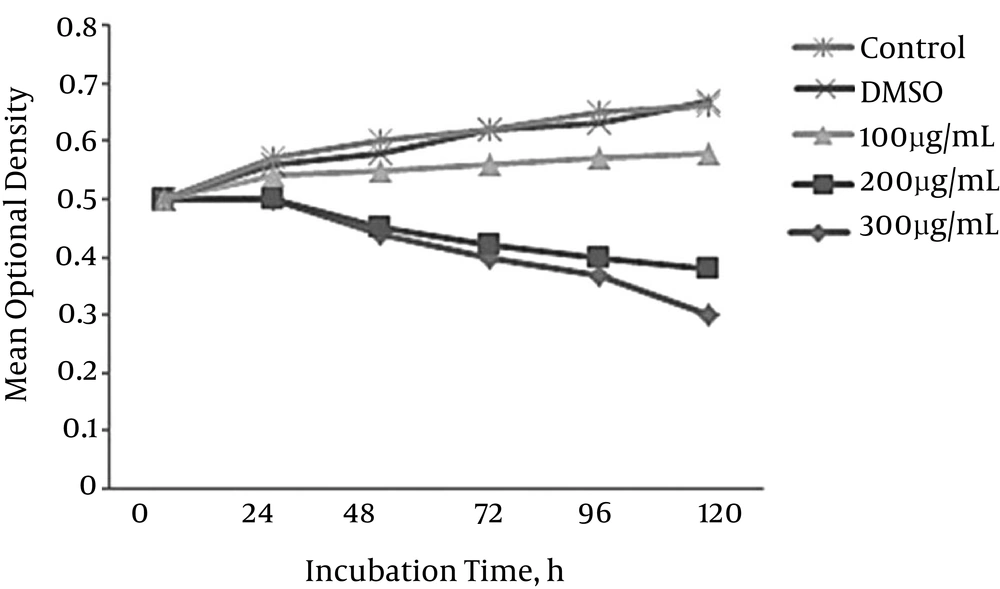

The bacteria were exposed to the different concentrations of cinnamaldehyde. The results in Figure 2 showed that 200 μg/mL of the cinnamaldehyde was the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the cinnamaldehyde, which inhibited the growth of M. tuberculosis. Therefore, M. tuberculosis was exposed to 200 μg/mL of the cinnamaldehyde in order to promote an alteration in gene expression of bacteria.

Real-time PCR was used to analyze gene expression in M. tuberculosis. Overall, there were 25 genes differentially regulated by the cinnamaldehyde. Among these, 12 genes exhibited a significant increase in the transcription and 13 exhibited a significant decrease in the transcription (Table 2).

| Gene Name | Description | Fold Change |

|---|---|---|

| frdA | Fumarate reductase subunit A | -3.1 |

| frdB | Fumarate reductase subunit B | -3.4 |

| frdC | Fumarate reductase subunit C | -3.2 |

| frdD | Fumarate reductase subunit D | -3.3 |

| narJ | Nitrate respiration | -3.3 |

| narI | Nitrate respiration | -3.0 |

| narH | Nitrate respiration | -3.5 |

| narG | Nitrate respiration | -3.2 |

| pks3 | Biosythesis of polyacyltrehalose | +3.9 |

| papA3 | Biosythesis of polyacyltrehalose | +3.4 |

| Mmpl10 | Biosythesis of polyacyltrehalose | +4.1 |

| rpsH | Ribosome proteins | +3.5 |

| rpsS | Ribosome proteins | +3.3 |

| rplW | Ribosome proteins | +3.3 |

| rplT | Ribosome proteins | +3.5 |

| rplO | Ribosome proteins | +3.2 |

| rplD | Ribosome proteins | +3.2 |

| rplB | Ribosome proteins | +3.9 |

| infC | Translation initiation factor IF-3 | +3.7 |

| rho | Ribosome proteins | +3.4 |

| argR | Arginine biosynthesis | -3.5 |

| argJ | Arginine biosynthesis | -3.2 |

| argG | Arginine biosynthesis | -3.1 |

| argF | Arginine biosynthesis | -3.1 |

| argD | Arginine biosynthesis | -3.4 |

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis of Gene Expressiona

5. Discussion

Four genes of frdA, frdB, frdC and frdD were down-regulated by 3.1-fold, 3.4-fold, 3.2-fold and 3.3-fold, respectively. The frdA genus has been found to be up-regulated in the M. tuberculosis in (7) as well as in studies that investigated the behaviour of the M. tuberculosis grown under carbon starvation (8). Studies on the behaviour of Mycobacterium phlei found that fumarate reductase (FRD) activity increased fourfold when the bacteria were grown under the low-oxygen conditions (9, 10). Fumarate reductase has reported to be a successful target in treatment of protozoan infections using a variety of compounds (11).

Nitrate reductase is a membrane-bound molybdenum-containing complex (12). Absorption of nitrogen into the mycobacterial metabolism is important for survival of M. tuberculosis (13). It is suggested that the narGHJI mediates nitrate absorption in M. tuberculosis (14).

The pks3 and mmpL10 genes were up-regulated by 3.9-fold and 4.0-fold, respectively. Suppression of papA3 gene expression from the M. tuberculosis resulted in loss of penta-acylated trehalose (PAT) (15-17). Pks3 is a polyketide synthase that is included in PAT biosynthesis of M. tuberculosis (18-20).

The rpsH and rpsS genes were up-regulated by 3.5-fold and 3.3-fold, respectively. Initiation factor infC was up-regulated by 3.7-fold and the transcription level of gene rho was also elevated by 3.4-fold. A work indicated that Clostridium difficile challenge to several concentrations of antibiotics resulted in a general up-regulation of translation machinery (21, 22).

L-arginine metabolism has indicated to be important for the M. tuberculosis (23). Some genes such as argR, argJ, argG, argF and argD were inhibited by 3.5-fold, 3.2-fold, 3.1-fold, 3.1-fold and 3.4-fold, respectively. Suppression of gene expression argR in Legionella pneumophila can affect gene transcript levels predicted to encode terminal steps of L-arginine biosynthesis (24). In Listeria monocytogenes, mutation of argD led to a decreased replication rates in Caco-2 cells (25). In Corynebacterium glutamicum, genes encoding L-arginine biosynthesis proteins showed a decreased expression in ammonium-limited chemostat cultures (26, 27).

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of the current study show that the cinnamaldehyde has potential antimycobacterial properties.