1. Background

The US Department of Health estimates that nosocomial infections result in an annual financial burden of $5 - 10 billion in healthcare expenses and cause 99,000 deaths. They are also a common cause of more serious consequences, increased mortality, and longer hospital stays (1, 2). The frequency of nosocomial infections, ranging from 5% to 15%, directly correlates with hospital quality. Treatment for nosocomial infections is expensive; however, over half of these infections can be managed, and their spread stopped, for significantly less money (3).

Nosocomial infections are one of the most frequent medical issues that hospitalized patients in intensive care units (ICUs) experience (4, 5). They affect 5% to 15% of patients in high-income countries, with 37% to 49% of these infections occurring in critical care units. Patients in ICUs often have immunosuppressive conditions, increasing their susceptibility to nosocomial infections (6). Hospitals in Southeast Asia (10%), the Eastern Mediterranean (11.8%), Europe (7.7%), and the Western Pacific (9%) report the highest rates of nosocomial infections. Research from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates that orthopedic and surgical units, as well as ICUs, have the highest incidence of nosocomial infections (7). More than 20% of nosocomial infection cases occur in the ICU department, with a raw mortality rate due to nosocomial infection in this department ranging from 10% to 80%. The most common causes of pneumonia are mechanical ventilation, intra-abdominal infections, and bacteremia secondary to intravenous injections, depending on vascularity (8, 9). This problem has been exacerbated by the development of transmissible resistance in pathogens to antibiotics (10). These infections occasionally result in patient deaths and pose a risk to those admitted to hospitals (11).

To assess the effectiveness of current infection prevention initiatives and develop future hospital and national intervention plans, accurate data on the prevalence of these infections are required. Consequently, identifying the origin and contributing factors of nosocomial infections and implementing suitable infection control strategies may reduce the risk of infection and the associated mortality in affected individuals (12).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to ascertain the incidence of nosocomial infections during the first nine months of 2018 in the ICU of Shohada-Ashayer Hospital in Khorramabad.

3. Methods

The current cross-sectional study was conducted at the special care unit of Shohada-Ashayer Hospital in Khorramabad, Iran, over a nine-month period, from April 1 to December 31, 2018.

3.1. Study Type and Entry and Exit Criteria

All patients admitted to the special care unit of Shohada-Ashayer Hospital in 2018 who exhibited symptoms of nosocomial infections (such as high fever, elevated heart rate, leukocytosis, and sputum) after a minimum of 72 hours of hospital stay were included based on the inclusion criteria. They underwent cultures in addition to radiological assessments, coughing, and other indications of possible nosocomial infection. The researchers adhered to ethical guidelines by maintaining the confidentiality of patient information throughout the research process.

3.2. Sample Collection

In this study, samples from all hospitalized patients suspected of having nosocomial infections based on clinical symptoms were collected on various culture media, including blood agar, chocolate agar, and eosin methylene blue. After incubation, the culture results were examined and identified using standard microbial tests such as gram staining, catalase, coagulase, citrate, indole, triple sugar iron (TSI), methyl red Voges-Proskauer (MR-VP), DNase, urea, and oxidation-fermentation (OF) tests (13). We then evaluated these results to determine the presence of nosocomial infections. Nosocomial infections are defined as infections that develop during hospitalization, where the infectious agent is acquired from the hospital environment. These infections do not exist in the patient upon admission and develop within 48 to 72 hours after hospitalization (14).

3.3. Determination of Microbial Susceptibility

The pattern of antibiotic resistance was determined using the disc diffusion method according to CLSI guidelines, employing antibiotic discs. The antibiotics tested included ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, imipenem, clindamycin, cefoxitin, amikacin, cefixime, piperacillin, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, meropenem, gentamicin, cotrimoxazole, azithromycin, rifampin, ampicillin, vancomycin, nitrofurantoin, cefepime, and cefazolin (Padtan Teb Co., Iran). These tests were performed on Mueller Hinton Agar (Merck, Germany) (15).

3.4. Data Analysis

SPSS version 22 was used to analyze the data. Depending on the type of variable, frequency, mean, and standard deviation calculations were utilized to establish the study's descriptive objectives.

4. Results

Out of 917 patients hospitalized in the special care units of Shohada-Ashayer Hospital, 92 patients suffered from nosocomial infections, resulting in a prevalence of 10%. These 92 patients hospitalized in the ICUs and special care units were examined for the frequency of nosocomial infections. The mean age of the studied patients was 61.23 ± 18.64 years, with the youngest patient being 18 years old and the oldest 95 years old. Among all the patients, 59 (64.1%) were male and 33 (35.9%) were female. The information of the studied patients is shown in Table 1. The highest rate of nosocomial infections was related to catheter infections (with positive clinical symptoms, positive blood culture, and positive catheter culture) at 40.3%, followed by urinary tract infections (UTI) at 33.7%.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| < 65 | 48 (52.2) |

| > 65 | 44 (47.8) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 33 (35.9) |

| Man | 59 (64.1) |

| History of infection | |

| Diabetes | 30 (32.6) |

| High blood pressure | 64 (69.6) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 41 (44.6) |

| Cancer | 1 (1.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (3.3) |

| The type of underlying disease leading to hospitalization of patients | |

| Stroke | 33 (35.9) |

| Multiple traumas | 26 (28.3) |

| Cardiovascular events | 5 (5.4) |

| Intracerebral hemorrhage | 17 (18.5) |

| Type of nosocomial infection | |

| Catheter | 37 (40.3) |

| Blood | 16 (17.4) |

| Urinary | 31 (33.7) |

| Respiratory | 8 (8.7) |

| Offensive devices | |

| Foley tube | 89 (96.7) |

| Stomach tube | 83 (90.2) |

| Central venous catheter | 15 (16.3) |

| Sheldon | 4 (4.3) |

| Sheldon tracheostomy | 32 (34.8) |

| Intubation | 83 (90.2) |

| Chest tube | 12 (13) |

The results of the examination of antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns are shown in Table 2. The highest rates of resistance were observed for cotrimoxazole (80.4%), ceftriaxone (72.8%), and ceftazidime (72.8%), while the highest rates of sensitivity were observed for ciprofloxacin (26.1%) and amikacin (23.9%). The most frequently isolated bacteria from the cultures of the studied patients were Acinetobacter spp. (28.3%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (17.4%), and Klebsiellapneumoniae (17.4%). The lowest frequency was related to Enterococcus spp. (1.1%) and Staphylococcusaureus (2.2%) isolated from the cultures of the patients (Table 3).

| Antibiotics | Resistance | Sensitive | Intermediate | Not Checked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | 63 (68.5) | 24 (26.1) | 4 (4.3) | 1 (1.1) |

| Ofloxacin | 13 (14.1) | 9 (9.8) | 1 (1.1) | 69 (75 ) |

| Clindamycin | 13 (14.1) | 1 (1.1) | - | 78 (84.8) |

| Gentamicin | 54 (58.7) | 21 (22.8) | 5 (5.4) | 12 (13 ) |

| Cefazolin | 70 (76.1) | 7 (7.6) | 1 (1.1) | 14 (15.2) |

| Cefepime | 48 (52.2) | 19 (20.7) | 3 (3.3) | 22 (23.9) |

| Meropenem | 50 (54.3) | 19 (20.7) | 1 (1.1) | 22 (23.9) |

| Piperacillin | 9 (9.8) | 4 (4.3) | 1 (1.1) | 78 (84.8) |

| Amikacin | 41 (44.6) | 22 (23.9) | 7 (7.6) | 22 (23.9) |

| Ceftriaxone | 67 (72.8) | 5 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | 19 (20.7) |

| Ceftazidime | 67 (72.8) | 10 (10.9) | 2 (2.2) | 13 (14.1) |

| Cefoxitin | 5 (5.4) | 7 (7.6) | - | 80 (87 ) |

| Cefixime | 14 (15.2) | 4 (4.3) | - | 74 (80.4) |

| Imipenem | 50 (54.3) | 20 (21.7) | 3 (3.3) | 19 (20.7) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 6 (6.5) | 7 (7.6) | 1 (1.1) | 78 (84.8) |

| Vancomycin | 7 (7.6) | 13 (14.1) | - | 72 (78.3) |

| Ampicillin | 57 (62 ) | 5 (5.4) | 3 (3.3) | 20 (21.7) |

| Rifampin | 8 (8.7) | 5 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | 78 (84.8) |

| Azithromycin | 5 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | - | 86 (93.5) |

| Cotrimoxazole | 74 (80.4) | 8 (8.7) | 1 (1.1) | 9 (9.8) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

| Bacteria | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 12 (13) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 10 (10.9) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 16 (17.4) |

| Acinetobacter | 26 (28.3) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 16 (17.4) |

| Enterococcus | 1 (1.1) |

| Streptococcus | 5 (5.4) |

| Corynebacterium | 4 (4.3) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2 (2.2) |

| Total | 92 (100) |

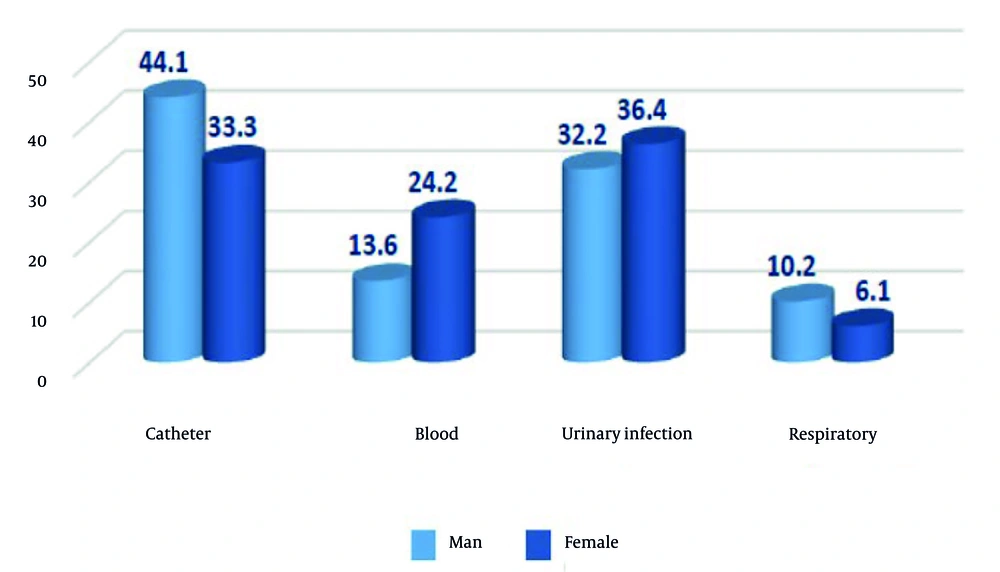

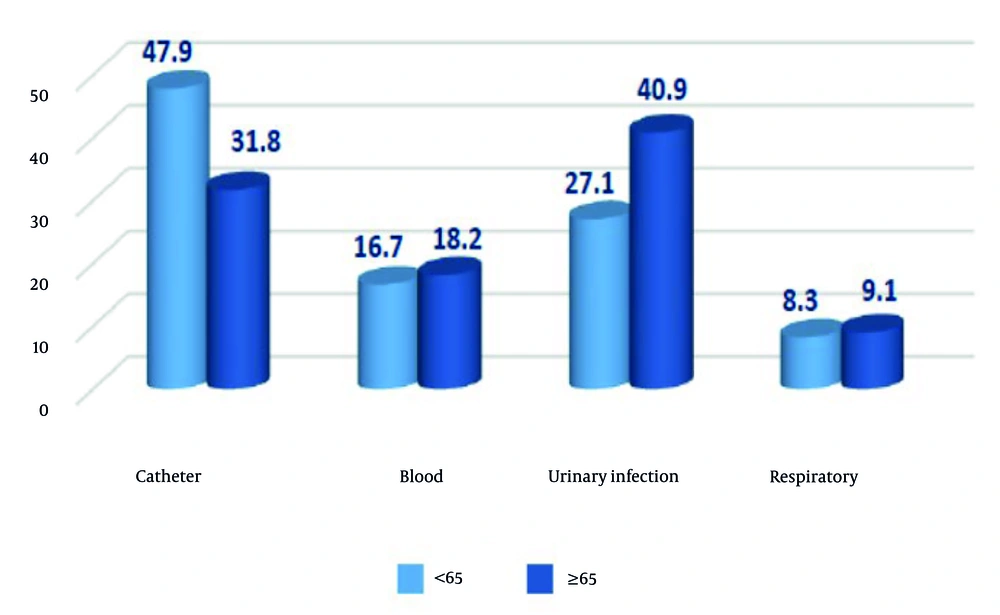

Based on the results from Figures 1 and 2 of the chi-square tests, the differences in the frequency of nosocomial infections by age (P = 0.419) and gender (P = 0.473) were not statistically significant. The differences in the frequency of nosocomial infections by history of diabetes (P = 0.828) and history of hypertension (P = 0.296) were also not significant, but there was a significant difference by history of cardiovascular diseases (P = 0.013). The most frequently isolated bacteria from patient cultures were Acinetobacterbaumannii (28.3%), P. aeruginosa (17.4%), and K.pneumoniae (17.4%). The least frequently isolated bacteria were Enterococcus spp. (1.1%) and S.aureus (2.2%). The frequency distribution of nosocomial infections was significantly different according to the type of bacteria (P = 0.001). The frequency of nosocomial infections in patients was not significantly different according to the type of inpatient department (P = 0.28). In the general ICU, the highest rate of nosocomial infections was catheter infection. In the surgical ICU, the highest frequency was related to urinary infection, and in the burn ICU, the highest frequency was related to blood infection. In the CCU, the frequency of catheter, blood, and urinary infections was 33.3% each, but these differences were not significant. The difference in the frequency of nosocomial infections in patients according to the type of antibiotic received in the first 24 hours was not significant (P = 0.666). The difference in the frequency of nosocomial infections in patients by the type of underlying disease leading to hospitalization in the ICU was not significant (P = 0.140). The difference in the frequency of patient outcomes by the types of nosocomial infections was not significant (P = 0.934), indicating no statistically significant relationship between patient outcome and the type of nosocomial infections. The difference in the distribution of the frequency of patient outcomes by the status of response to antibiotics in the first 24 hours was not significant (P = 0.211). The difference in the distribution of the frequency of nosocomial infections in patients according to the status of response to antibiotics prescribed in the first 24 hours was not significant (P = 0.774).

5. Discussion

The prevalence of nosocomial infections is closely related to the level of hospital hygiene; in hospitals with advanced health systems, this rate is less than 5%. Due to the severity of the disease, the length of hospitalization, and the use of invasive methods, the ICU is one of the high-risk areas for nosocomial infections (16-19)). In this study, the prevalence of nosocomial infections was 10%, consistent with the findings of Amini (20). In contrast, the study by HajiBagheri and Afrasiabian reported a prevalence rate of 15.6% (21). This difference could be due to the variation in the number of examined beds in the care units. According to international standards, the acceptable level of nosocomial infections for developed countries ranges from 5% to 20%, and the prevalence observed in this study aligns with these standards (12, 22-24).

Regarding the type of nosocomial infections, the highest frequency was related to catheter-associated infections at 40.3%, followed by urinary infections at 33.7%. The results of this study and those by Fereidooni Moghadam et al. showed that the most common nosocomial infections in special care departments were related to arterial and venous catheters (88%), which is consistent (25). The study indicated that the highest frequency of bacteria isolated from patient cultures was A.baumannii (28.3%), P. aeruginosa (17.4%), and K.pneumoniae (17.4%). This finding is consistent with Yaghubi et al.'s study (26) and Amini (20), but not with K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Enterobacter spp. in HajiBagheri and Afrasiabian's study, possibly due to a higher rate of intubation in their patients (21).

The study showed the highest resistance rates to cotrimoxazole (80.4%), ceftriaxone (72.8%), and ceftazidime (72.8%), while the highest sensitivity was to ciprofloxacin (26.1%) and amikacin (23.9%). These results align with Bahrami et al.'s study (27) but differ from Yaghubi et al.'s study (26), likely due to variations in the organisms isolated and their prevalence in hospital environments. The relationship between the prevalence of nosocomial infections and age, sex, and history of previous diseases was significant. In the surgical ICU, the highest frequency of nosocomial infections was related to UTI, consistent with Hussainrezaee et al.'s study (28). In the burn ICU, the highest frequency was related to blood infections, consistent with Askaryan et al.'s study (29). In the CCU, the frequency of catheter, blood, and urinary infections was 33.3% each; however, this study found no statistically significant difference between the types of infections, hospitals, and the type of inpatient ICU (P < 0.05).

5.1. Conclusions

According to the results, it can be concluded that the prevention of nosocomial infections requires precise and well-planned activities and programs. These can include the correct and timely use of medical interventions to limit the transmission of microorganisms, such as handwashing, especially by healthcare workers, infection monitoring and diagnosis, epidemic control, health education, continuous monitoring at the hospital level, proper use of disposable devices, controlled use of antibiotics, and careful wound care.