1. Background

In various healthcare professions, any form of skin piercing by needles or sharp objects, either accidental or during medical and nursing interventions, is considered a needle stick. If an individual comes into contact with an infected needle or sharp object at the time of the needle stick, they may be exposed to serious health issues, including contagious diseases. Splashes of infectious discharges from patients into the eye, open wounds, and exposed mucous membranes may also cause infections to enter individuals’ bodies (1).

According to the World Health Organization, each year, about three million individuals out of the 35 million healthcare workers experience needle sticks (2). Different groups of healthcare workers, including dentists, are exposed to needle stick injuries. The frequency of needle sticks in Middle Eastern countries is about 50 percent. For instance, the frequency of needle stick injuries in Pakistan and Turkey is 45% and 46.8%, respectively, which is mostly due to high work pressure (3). In our country, the needle-stick frequency in Khorram Abad, Astara, and Kurdistan was reported as 53%, 67%, and 58%, respectively, primarily due to night work shifts and lack of patient education (3).

Despite significant advances in medical science, dangerous diseases, including Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV), and Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), remain serious risks for healthcare workers, as various reports indicate that 90 percent of needle stick-caused injuries occur in developed countries (3, 4). According to a study conducted by Baig et al., which aimed to investigate the knowledge and attitude of dental professionals, students, and other related staff towards needle sticks and sharp object injuries, 97% of the participants were aware of needle sticks and their dangers, and 72% of them had experienced needle stick injuries (5).

A study conducted in 2022 at Johannesburg University (South Africa) reported a 47.2% needle stick frequency among dentists, with 35% occurring when swapping the anesthesia ampoule and 29% when recapping the needle (6). Results of a 2021 study in Saudi Arabia estimating the annual incidence rate of needle sticks and its related factors conducted on 361 healthcare workers reported a 22.2% annual rate, with dentists accounting for 29.2% of the cases (7). The results of Anbari et al. indicated that 84.4% of dentists had experienced a needle stick at least once, with needles being the most common factor (20%) (8). Researchers in Croatia investigated the frequency of occupational injuries among dentists and reported needle sticks (57.5%) and cuts (20.8%) as the most common injuries (9). Results of Bhardwaj et al. in Malaysia reported that needle stick injuries were more frequent in male individuals (10). Gholizadgougjehyaran et al. found that the frequency of needle stick injuries in nurses decreased with an increase in education level (11). Rashidi et al. reported that the frequency of needle sticks among nurses who work in hospitals was 53% and demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between work shifts, work experience, and the service ward and the occurrence of needle sticks among the nurses (3).

A study by Ramzani et al. on active nurses in Sari City hospitals reported a 38% frequency of needle sticks. In this study, needle sticks had the highest frequency among sharp object injuries, believed to be due to high work pressure (12). According to the results of a study in Sina Hospital of Mashhad city, the level of attention to preventing injuries increased with healthcare workers’ higher ages and working experience. Regarding the type of incident, needle sticks accounted for 25 percent of the sharp object injuries (13).

2. Objectives

Considering the findings obtained from the studies mentioned above and the high frequency of needle sticks among healthcare workers, especially dentists, and since the cause of such occupational accidents among dentists has been neglected, the present study investigated the frequency and causes of needle stick and sharp object injuries among the dentists of Lorestan province, west of Iran.

3. Methods

The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences (IR.LUMS.REC.1402.389). This analytical cross-sectional study included all active dentists in Lorestan province, west of Iran, who met the designated conditions and inclusion criteria in 2023. According to a similar study that reported a prevalence rate of 57.7 percent (3), the sample size was calculated as 260 people based on the above prevalence rate, α = 0.05, and an accuracy of 6 percent. Employment as a dentist and being unwilling to participate in the study were considered inclusion and exclusion criteria, respectively.

A total of 218 dentists were selected from 11 cities in Lorestan province using stratified proportional allocation sampling. Each city in Lorestan province was considered a subgroup, and simple random sampling was conducted from each city according to the number of active dentists in each city. The data collection tool included a checklist with two primary sections. The first section contained six demographic questions regarding age, sex, work experience, work shift, type of specialty, and the dentist’s office type. The second section included five specialized questions about the type of injury, needle sticks, and several related questions following each specialized question. This checklist has been validated in the study by Rashidi et al. (3).

The checklists were completed by the researcher visiting dental offices and using observation and interview methods. After collecting the required information, descriptive statistics, including calculating central and dispersion indices for quantitative variables and frequency and percentage for qualitative variables, were used to describe the data. Chi-square tests were used to examine the relationship between the desired variables. All statistical tests were performed using SPSS version 25 software, and P < 0.05 was considered the significance level.

4. Results

Out of the 218 samples in the present study, 120 participants were male, and 98 were female. Of these, 46 (21.1%) were aged less than 30, 105 (48.2%) were between 30 and 40, and 67 (30.7%) were older than 40. The minimum age of the dentists was 25, and the maximum was 57 years, with a mean and standard deviation of 35.85 ± 6.95 years. A total of 202 (97.7%) dentists had experienced needle sticks, while 16 (7.3%) had not. Table 1 presents additional demographic information.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Needle experience | |

| No | 16 (7.3) |

| Yes | 202 (92.7) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 98 (45) |

| Male | 120 (55) |

| Age | |

| < 30 | 46 (21.1) |

| 30 - 40 | 105 (48.2) |

| > 40 | 67 (30.7) |

| Level of education | |

| General physician | 203 (93.1) |

| Specialist | 15 (6.9) |

| Working shift | |

| Morning | 58 (26.6) |

| Evening | 84 (38.5) |

| Morning and evening | 76 (34.9) |

| Work experience (y) | |

| < 5 | 60 (27.5) |

| 5 - 10 | 88 (40.4) |

| 10 -15 | 60 (27.5) |

| > 15 | 10 (4.6) |

| Place of service | |

| Public facility | 84 (38.5) |

| Private sector | 69 (31.7) |

| Public and private | 65 (29.8) |

Results indicate that needle sticks, splashes in the eye, and broken vials, with frequencies of 101 (46.3%), 77 (35.3%), and 50 (22.9%), respectively, were the most common types of sharp object injuries (Table 2).

| Needle Stick Type | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Needle | 101 (46.3) |

| Splash in the eye | 77 (35.3) |

| Mucous membrane exposure | 60 (27.5) |

| Surgical suture | 59 (27.1) |

| Broken vial | 50 (22.9) |

| Bistoury | 13 (6) |

Investigation of needle stick causes indicated that all the dentists were aware of the dangers of needle sticks, and none of them cited lack of knowledge as the cause of the needle stick incidents (Table 3).

| Cause of Needle Stick Incidence | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| High work pressure | 145 (66.5) |

| Inattention | 98 (45) |

| Lack of protective equipment | 37 (17) |

| Lack of knowledge | 0 (0) |

The present study revealed that 38 individuals (18.8%) who had needle stick experience were aged less than 30, and 67 (33.2%) were over 40. The chi-squared test indicated a significant relationship between age and needle stick experience (P = 0.002) (Table 4).

| Variable | Needle Experience | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Age (y) | 0.002 | ||

| < 30 | 8 (50) | 38 (18.8) | |

| 30 - 40 | 8 (50) | 97 (48) | |

| > 40 | 0 (0) | 67 (33.2) | |

| Total | 16 (100) | 202 (100) | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Results showed that among those with needle stick experience, 51 (25.2%) were active in morning shifts, 76 (37.6%) in evening shifts, and 75 (37.1%) were active in both morning and evening shifts. The chi-squared test indicated a significant relationship between work shift and needle stick experience (P = 0.038) (Table 5).

| Variable | Needle Experience | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Work Shift | 0.038 | ||

| Morning | 7 (43.8) | 51 (25.2) | |

| Evening | 8 (50) | 76 (37.6) | |

| Morning and evening | 1 (6.3) | 75 (37.1) | |

| Total | 16 (100) | 202 (100) | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

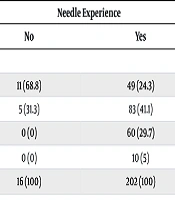

The present study indicated that among those with needle stick experience, 49 (24.3%) had less than five years of work experience, 83 (41.1%) had between 5 and 10 years, 60 (29.7%) had between 10 and 15 years, and 10 (5%) had more than 15 years of work experience. The chi-squared test indicated a significant relationship between work experience and needle stick experience (P = 0.001) (Table 6).

| Variable | Needle Experience | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Work experience (y) | 0.001 | ||

| < 5 | 11 (68.8) | 49 (24.3) | |

| 5 - 10 | 5 (31.3) | 83 (41.1) | |

| 10 - 15 | 0 (0) | 60 (29.7) | |

| > 15 | 0 (0) | 10 (5) | |

| Total | 16 (100) | 202 (100) | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Regarding the condition of the dentists’ protective equipment against needle sticks within the service organization, the chi-squared test indicated a statistically significant relationship between the type of organization where the dentists were active and the lack of protective equipment (P < 0.001) (Table 7).

| Variable | Lack of Protective Equipment | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Organization | 0.001 | ||

| Public | 65 (77.4) | 19 (22.6) | |

| Private | 69 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Public and private | 47 (72.3) | 18 (27.7) | |

| Total | 181 (100) | 37 (100) | |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

The findings of the present study indicated that there was no statistically significant relationship between other variables, including sex, level of education, dentist’s service organization, and the frequency of needle sticks.

5. Discussion

Needle sticks in hospital environments and healthcare centers are incidents that can impose significant mental and financial burdens on individuals and society. Despite various causes of needle sticks, including excessive and unnecessary injections, lack of appropriate equipment and disposable syringes, absence of sharp object-exclusive containers, and inadequate training of healthcare workers, the risk factors of needle sticks are still not fully understood, as needle sticks remain a persistent health threat to healthcare providers (14).

The present study indicated that 202 (92.7%) of the 218 participating dentists had experienced needle sticks or contact with patients' body discharges. This frequency was higher than in other studies conducted in this field (15-18). Gholami et al. reported a frequency of 39% in Urmia (19). The study conducted by Askarian in Fars province revealed a 49% frequency (20). According to Farzin Ebrahimi et al., 80% of dentists have experienced at least one needle stick injury (21). According to a study by Shiva et al., more than 50% of dentists had poor knowledge about hepatitis B and the consequences of needle stick injuries (22).

The differences in the number of needle stick cases in various studies may be attributed to the definition and understanding of researchers regarding needle sticks in their studies and the duration of the studies. In some studies, every injury caused by sharp objects, such as needles and other sharp tools, and even splashes of patient discharges into the eye and mucous membrane, were considered needle sticks. However, in others, only cases involving injection needles were considered needle sticks. In the present study, 101 (46.3%) participants experienced needle stick accidents by injection needles, 50 (22.9%) by broken vials, 77 (35.3%) by splashes of body discharges into the eyes, 13 (6%) by bistoury, 60 (27.5%) by splashes of body discharges into the mucous membrane, and 59 (27.1%) by surgical suture.

In Farzin Ebrahimi et al., the most common causes of needle stick injuries in dentists included dental burrs (33.9%), needles (19.6%), orthodontic archwire (10.7%), dental elevator (8.9%), and matrix holders (5.4%). Among dental assistants, washing, picking up, or placing the tools on the tray (44.4%), needle (27.8%), and dental burr (16.7%) were the primary causes (21). Hashemipour and Sadeghi’s investigation of the frequency of needle stick injuries among medical and dental students at Kerman University of Medical Sciences demonstrated that dental students in the endodontics, surgery, and periodontics groups had the highest frequency of accidents (23).

Examination of needle stick incident causes in the present study revealed that all dentists were aware of the dangers of needle sticks, and none of them mentioned lack of knowledge as the cause of needle sticks. Instead, 98 dentists (45%) mentioned inattention during work, 145 (66.5%) cited high work pressure, and 37 (17%) stated lack of protective equipment as the cause of needle stick accidents. Other studies have also cited high work pressure and unsafe equipment as causes of accidents (24, 25).

When investigating the reason for not using protective equipment by dentists, 7 (3.2%) mentioned lack of adequate training, 96 (44%) cited high work pressure, 112 (51.4%) mentioned the necessity of working fast, and 71 (32.6%) stated lack of supervision as reasons for not utilizing protective equipment. This study revealed that among those who had experienced needle sticks, 51 (25.2%) were active in morning shifts, 76 (37.6%) in evening shifts, and 75 (37.1%) in both morning and evening shifts. The chi-squared test indicated a significant relationship between work shift and needle stick experience, as those who worked evening shifts or both morning and evening shifts had higher frequencies of needle stick incidents.

The results of Ghasemi et al. (as cited by Garavand et al.) showed that in both groups of hospital workers and nurses, most needle stick incidents occurred during morning shifts (26). The high frequency of needle stick injuries on the morning shift can be attributed to the high number of accepted surgery candidates and the high workload for nurses during morning shifts. However, as mentioned earlier, most needle stick injuries in the present study occurred during evening shifts and continuous morning and evening shifts. The inconsistency of the results may be due to the different nature of dentists’ work compared with other medical professions and how they utilize sharp tools.

The present study indicated that among those who had needle stick experience, 49 individuals (24.3%) had less than five years of work experience, 83 (41.1%) had between five and ten years, 60 (29.7%) had between 10 and 15 years, and 10 (5%) had more than 15 years of work experience. The chi-square test showed a significant difference between work experience and needle stick experience, as the risk of needle sticks increased with the increase in work experience of the dentist. Despite the fact that longer work experience can enhance working skills, some investigations on occupational accidents have shown that because of pride and overconfidence in work experience, individuals with longer work experience neglected work safety and consequently suffered occupational injuries (27, 28).

The present study indicated that none of the individuals active in private clinics stated lack of protective equipment as the cause of needle stick accidents, while 19 (22.6%) of those who worked in public organizations mentioned lack of protective equipment as a cause for needle stick incidence. This demonstrates that the weakness in providing protective equipment in the public sector is among the factors of occupational contamination in dental clinics.

5.1. Conclusions

Considering the results of the present study and the high rate of needle sticks among healthcare workers, especially dentists, and due to the adverse consequences of such incidents, further studies are necessary to understand the behavioral and organizational factors involved in injuries caused by sharp objects and their dangerous outcomes. Research should focus on prevention strategies, reporting protocols, post-exposure treatments, and necessary education. In addition to medical measures, healthcare system officials must establish centers for prevention and control of injuries, regularly register incidents, and take appropriate follow-up actions.