1. Background

Hepatitis B infection is one of the major and common liver infectious diseases worldwide (1). Importantly, there are globally 350 - 400 million chronic carriers of hepatitis B virus (HBV) (2). Routes of infection include vertical transmission (through childbirth), early life horizontal transmission (bites, lesions, and sanitary habits), and adult horizontal transmission (such as sexual contact and intravenous drug use) (3).

Indeed, the presence of the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in serum is the first serum marker to indicate the HBV infection (4). Although, other HBV infection serological markers are hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) as well as antibodies against hepatitis B core (anti-HBc) and e (anti-HBe) antigens. These markers can be used for diagnosis and determining the severity of the infection (5).

The prevalence of HBV infection varies widely, with rates ranging from 0.1% to 20% through the worlds (6). Iran has been known as an intermediate prevalence area of the infection i.e., 2% to 7% HBsAg seropositivity. The first estimate of the prevalence of HBV infection, about 30 years ago, indicated that approximately 35% of Iranians are exposed to HBV, and 3% are chronic carriers (7). However, a recent systematic review study cleared that HBV infection prevalence among Iranian general population is estimated as 2.14% (8).

Nonetheless, there are few data on the HBV seroprevalence and the related risk factors of hepatitis B among the general population in Northeastern Iran. A population-based study by Fathimoghaddam et al. (9), showed that the overall prevalence of HBsAg seropositivity in Mashhad is 1.4%; the prevalence among males and females were 2.0% and 0.9%, respectively. The infection was more prevalent in older and married persons and those with a history of traditional cupping.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of serological markers and potential risk factors of HBV infection among individuals who referred to a great medical diagnostic center in Neyshabur, northeast of Iran.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed in the medical lab of the Academic Center for Education, Culture, and Research (ACECR) in Neyshabur. All persons who referred to test HBsAg seropositivity were enrolled. No specific criteria were considered to include in or exclude from the study. Totally, 2669 individuals were surveyed during June 2015 to February 2016.

After obtaining informed consent, all participants were interviewed in detail, and the data were recorded in a prescribed questionnaire. These included; age, gender, marital status, residence place, ethnicity, household size, education, income, and histories of blood transfusion, hospitalization, surgery, dentistry procedure, traditional cupping, and tattoos as well as the reasons of requesting HBsAg test.

The HBsAg was detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method (DSI s.r.l., Italy) and all reactive samples were analyzed to detect other markers of HBV infection, using ELISA commercial kits, according to manufacturers’ companies. These included HBeAg, anti-HBe, total anti-HBc (Dia.pro, Italy), and IgM anti-HBc (General Biological Crop., Taiwan). This study was approved and supervised by a scientific board in ACECR, Razavi Khorasan Branch, regarding methodological and ethical issues (ACECR 93.48.1707).

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software ver.16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) by chi-Square test. The P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

The mean age of 2669 participants was 32.4 ± 13.1 years (Range: 1 - 93 years), of which 2099 (78.6%) were female, and 2431 (91.1%) were married. Nearly all participants (96.4%) were born in Neyshabur, and 2383 (89.3%) were from urban areas. Distribution of educational level was as follow: 163 (6.1%) illiterate, 392 (14.7%) primary school, 1516 (56.8%) secondary and high school, and 598 (22.4%) academic education.

Screening of HBV infection during pregnancy (51.2%) and routine medical check-up (29.4%) were the most common reasons for which the participants were referred to test serum HBsAg (Table 1).

| Reasons | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| During pregnancy | 1368 (51.2) |

| Routine check up | 784 (29.4) |

| Having some clinical or lab evidences suggesting hepatitis | 320 (12.0) |

| Being candidate for a surgical operation | 115 (4.3) |

| Having a positive family history of HBV infection | 39 (1.5) |

| Visa application | 43 (1.6) |

4.1. Prevalence of HBsAg Positivity

A total of 90 cases with hepatitis B surface antigenemia (3.37%, CI 95%: 2.72 - 4.13) were detected. All cases with a positive HBsAg test had also a positive result for total anti-HBc test. Likewise, IgM anti-HBc, HBeAg, and anti-HBe markers were positive in 11 (12.22%), 8 (8.89%), and 75 (83.33%) individuals with HBsAg seropositivity, respectively (Table 2).

| HBV Serological Markersa | No. (%) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| IgM anti-HBc(+), HBeAg(±), anti-HBe (±) | 11 (12.22) | Recent hepatitis B infection |

| IgM anti-HBc (-), HBeAg (+), anti-HBe (-) | 4 (4.44) | Chronic hepatitis B infection, high infectivity |

| IgM anti-HBc (-), HBeAg (-), anti-HBe (+) | 73 (81.11) | Late acute or chronic hepatitis B, low infectivity/HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B infection |

| IgM anti-HBc (-), HBeAg (-), anti-HBe (-) | 2 (2.22) | Unclear interpretation |

aTotal anti-HBc test was positive in all cases.

Expectedly, HBsAg seropositivity was more prevalent in people who referred because of having some clinical or lab evidences of hepatitis or in those with a positive family history of HBV infection (42/359; 11.70%) than pregnant women, candidates for an operation, individuals who requested a routine check-up, and those who applied a visa (48/2310; 2.08%) (P < 0.001).

4.2. Risk Factors of HBsAg Seropositivity

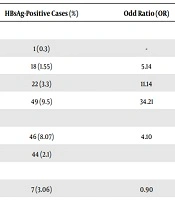

The data demonstrated a growing trend in the prevalence of HBV infection with increasing participant’s age (P < 0.0001). Furthermore, gender (P < 0.0001), household size (P < 0.0001), and educational level (P < 0.0001) were significant demographic risk factors of HBsAg seropositivity (Table 3). On the other hand, HBsAg seropositivity were not associated with marital status, residence place, ethnicity, and income. As illustrated in Table 4, none of the risky procedures such as blood transfusion, hospitalization, surgery, dentistry procedure, traditional cupping, and tattooing had a significant association with HBsAg seroreactivity.

| Variable | No. | HBsAg-Positive Cases (%) | Odd Ratio (OR) | OR 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | < 0.0001 | ||||

| < 20 | 327 | 1 (0.3) | - | - | |

| 20 - 29 | 1160 | 18 (1.55) | 5.14 | 0.68 - 38.64 | |

| 30 - 39 | 666 | 22 (3.3) | 11.14 | 1.49 - 82.99 | |

| ≥ 40 | 516 | 49 (9.5) | 34.21 | 4.70 - 248.97 | |

| Gender | < 0.0001 | ||||

| Male | 570 | 46 (8.07) | 4.10 | 2.68 - 6.27 | |

| Female | 2099 | 44 (2.1) | |||

| Marital status | 0.782 | ||||

| Single | 229 | 7 (3.06) | 0.90 | 0.41 - 1.96 | |

| Married | 2440 | 83 (3.4) | |||

| Residence place | 0.087 | ||||

| Rural | 286 | 15 (5.24) | 1.63 | 0.93 - 2.86 | |

| Urban | 2383 | 75 (3.15) | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.202 | ||||

| Fars | 2583 | 85 (3.29) | 0.55 | 0.22 - 1.40 | |

| Others | 86 | 5 (5.81) | |||

| Household size | < 0.0001 | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 983 | 13 (1.32) | 3.57 | 1.97 - 6.46 | |

| > 2 | 1686 | 77 (4.57) | |||

| Education, y | < 0.0001 | ||||

| < 9 | 946 | 52 (5.50) | 2.34 | 1.55 - 3.54 | |

| ≥ 9 | 1731 | 42 (2.4) | |||

| Income (monthly), USD | 0.101 | ||||

| < 300 | 2140 | 58 (2.71) | 0.60 | 0.32 - 1.11 | |

| ≥ 300 | 529 | 32 (6.05) |

| Variable | No. | HBsAg-Positive Cases (%) | Odd Ratio (OR) | OR 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood transfusion | 0.953 | ||||

| Yes | 28 | 1 (3.57) | 1.06 | 0.14 - 7.90 | |

| No | 2641 | 89 (3.37) | |||

| Surgery | 0.382 | ||||

| Yes | 362 | 15 (4.14) | 1.29 | 0.73 - 2.27 | |

| No | 2307 | 75 (3.25) | |||

| Dentistry procedures | 0.286 | ||||

| Yes | 216 | 10 (4.63) | 1.44 | 0.73 - 2.82 | |

| No | 2453 | 80 (3.26) | |||

| Traditional cupping | 0.958 | ||||

| Yes | 145 | 5 (3.45) | 1.02 | 0.41 - 2.58 | |

| No | 2524 | 85 (3.37) | |||

| Hospitalization | 0.155 | ||||

| Yes | 343 | 16 (4.66) | 1.49 | 0.86 - 2.59 | |

| No | 2326 | 74 (3.18) | |||

| Tattooing | 0.358 | ||||

| Yes | 24 | 0 (0) | - | - | |

| No | 2645 | 90 (3.40) |

5. Discussion

Iran has been known as an endemic area of HBV infection with an intermediate level (2% - 7%) (10). The current study showed the same level of the infection prevalence (3.37%) in a non-random sample of the population from Neyshabur, northeast of Iran.

Among persons with HBsAg positivity, 8.9% showed HBeAg positivity that reflects active hepatitis and high infectivity. These patients are at increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which impose a heavy burden on the public health system (11).

Although this population is not representative for the general population, in the present study, the prevalence of HBV infection was considerably higher than that estimated among the general population of the country (2.14%) (8). The higher hepatitis B infection rate in our study is completely expected because a part of them had some clinical or lab evidence suggesting hepatitis, and some had a positive family history of HBV infection.

A study in 2011 showed the HBsAg positivity of 1.4% in Mashhad. HBsAg positivity among people with the risk factors of blood transfusion, hospitalization, surgery, dentistry procedure, traditional cupping, and tattooing were 3.17%, 1.28%, 1.63%, 2.59%, 3.77%, and 3.43%, respectively (9), while these amounts in our study were 3.57%, 4.14%, 4.63%, 3.45%, 4.66%, and 0%, respectively. It seems that HBsAg positivity among individuals with the risk factors of HBV infection, except tattooing, has a low percentage in Mashhad in comparison to ones in Neyshabur.

Furthermore, a survey in 2012 reported a much lower prevalence of HBV infection (0.75%) in Kermanshah, west of Iran. Predictors of HBsAg over multivariate analysis were old age, being male, history of tattooing, and history of the dental procedure (11). These results are in agreement with our study in terms of being aged and male, whilst other risk factors could not consider as a predictor of HBV infection.

Studies from some other countries present a higher rate of HBV infection. The adjusted seroprevalence of HBsAg in South Korea in 2009 was 4%. Similar to our study, HBsAg positivity was higher among older people (12). Additionally, the prevalence of HBsAg in young adults in Banjarmasin, Indonesia, was 4.6% (13). Furthermore, a comprehensive study in Singapore showed that the prevalence of HBsAg seropositivity was 3.6% in 2010 (14).

Our result cleared a significant relation between HBV infection and participant’s age, gender, educational level, and household size. The HBsAg prevalence in young adults vaccinated against HBV as the first group of Iranian neonates during 1993 and 1994 had investigated by Saffar et al., in 2014 (15). They found neither HBsAg positive nor symptomatic hepatitis cases. Similarly, Alavian et al. (11), showed that age and gender are major risk factors of HBV infection in Kermanshah province, west of Iran. Moreover, a population-based study in Mashhad reported a higher prevalence of HBsAg positivity among males than females and demonstrated a rising trend in the prevalence with an increase of participants’ age (9). In addition, Merat et al. (16), showed that older age, high school education, and living in a rural area had a significant relation with HBV infection. On the other hand, Fathimoghaddam et al. (9), could not find any association between HBV infection and literacy and household size.

We have previously surveyed the HBsAg prevalence among people older than five years in Neyshabor between 2011 to 2015, in which the results demonstrated 4.11% of people suffer from HBV infection (17). Similar to the current report, there was a significant relationship between HBV infection and demographic factors of age and gender. In addition, we showed a higher prevalence in the previous five years in Neyshabur, which accordingly, we can claim the rate of infection decreased by the passage of time (17). Our another study (18), demonstrate that 1.09% of pregnant women were positive with HBsAg.

Based on the global hepatitis report, 2017, all countries should seize the opportunities to eliminate viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030 (reducing new infections by 90% and mortality by 65%) (19). The Polaris Observatory (TPO) Collaborators estimate the global prevalence of HBsAg in the general population by a modeling study in 2016. This study has reported, corresponding to 292 millions infections, that the global prevalence of HBsAg in 2016 was 3.9 % (20).

This survey could not show a significant relation between HBsAg positivity and some potential risky procedures and conditions such as blood transfusion, hospitalization, surgery, dentistry procedure, traditional cupping, and tattooing. Consequently, another study in Mashhad found no association between HBV infection and above-mentioned variables (except cupping) (9). In contrast, Alavian et al. (11), showed that the history of tattoo and dental procedures are important risk factors of HBsAg seropositivity in Kermanshah.

5.1. Conclusions

HBV infection prevalence in Neyshabur, northeast of Iran is considerably higher than that reported from several regions of the country. The higher hepatitis B infection rate in the current study is completely expected, due to the fact that some reasons for which individuals referred, were suggesting hepatitis. In spite of this fact, the implementing of efficient measures such as mass educational programs by local health authorities to control infection is strongly recommended.