1. Background

Coronavirus NL63 is a species of Coronaviridae family. These viruses are enveloped with a phospholipid double layer, containing positive sense single-strand (1). The family includes two subfamilies, Coronavirinae and Torovirinae. The Coronavirinae subfamily is divided into four subgroups, including alpha, beta, gamma, and Delta corona virus, primarily based on the phylogenetic division (2). The size of the genome is approximately 33 - 26 kb, which is largest among other RNA virus genomes and have cap and polyadenine at the two ends of 5’ and 3’ (3). In the genomic structure, two-thirds of the 5’ genome contain ORF1a and ORF1b while in the 3’ region, four structural proteins called spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) are found. The hemagglutinin esterase (HE) gene is a characteristic of the second group of coronaviruses that is not present in the HCoV-NL63 virus (4).

Coronaviruses are distributed worldwide and are one of the most common causes of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) in adults (5). These viruses can infect humans and various types of pets and cause diseases such as respiratory infection, gastroenteritis, cardiovascular diseases, and neurological disease. So far, six human coronaviruses have been identified, including OC43, 229E, NL63, HKU-1, SARS, and MERS, of which SARS and MERS have the highest mortality and OC43, 229E, NL63, and HKU-1 have lower mortalities (6-8). These viruses are believed to have animal reservoirs and be zoonotic. The most important reservoirs are dromedary camel, bovine, and bats. Currently, the reservoir of the HKU-1 virus is unkonwn (9-11).

The HCoV-NL63 virus from the α coronavirus group was first identified in a child with bronchiolitis in Holland in 2004 (12). In China, the HCoV-NL63 virus is the main respiratory pathogen in infants and the elderly. Lower respiratory infections include 30% of all respiratory infections and can cause severe respiratory illnesses in infants, young children, the elderly, and people with immunodeficient systems (13, 14). Some of these viruses, like SARS, can cause fatal infections. Therefore, timely diagnosis can prevent transmission to other immunosuppressed children (15). Epidemiological studies have shown that viral respiratory infections, such as influenza and parainfluenza infections in children, reach their peak at the end of autumn or winter, and children present with symptoms similar to influenza infection. These symptoms are more similar to diseases caused by coronaviruses, especially HCoV-NL63. Infection with this virus generates symptoms similar to influenza infection, which prevents children from receiving proper treatment. This causes children suffering from pneumonia and respiratory distress to be admitted in the intensive care unit or may lead to even death (16, 17). Therefore, this study determined the frequency of coronavirus NL63 infection in young children aged less than five years.

2. Objectives

Coronavirus infection does not have a specific symptom and may be confused with other viral infections. A failure in proper, timely treatment can cause irreparable harm to children. This study aimed to determine the frequency of coronavirus NL63 infection in children under five-years-old with an upper respiratory infection and its association with clinical manifestations and dispersal rates in different age and sex groups.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients

In a cross-sectional study, we enrolled 138 children under five-years-old with acute respiratory infections admitted to the Pediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (PNICU) of Afzalipoor Hospital, Kerman Province, for 11 months from October 2018 to December 2019. Oral-pharyngeal swab samples were collected in tubes containing sterile normal slain. Hospitalized children only had a respiratory infection and they had no immunodeficiency disease, heart failure, and blood disorder.

3.2. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study (reg. no.: 96000908) was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kerman University of Medical Sciences. The ethical approval code is IR.KMU.REC.1397.134. All parents provided written informed consent as per the international guidelines.

3.3. Viral RNA Extraction

Oral and nasal pharynx samples were collected using Dacron swabs in Viral Transport Media (VTM) containing DMEM and antibacterial agents (penicillin and streptomycin). Viral RNA was extracted from a 100 µL volume of samples by a precipitation method (RIBO-prep, ILS). Briefly, the specimen was added to a tube containing 300 µL of lysis buffer and 400 µL of the precipitate buffer, mixed, incubated for 10 min at room temperature, and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for three minutes. Then, it was washed once with 500 µL of wash buffer W3 and once with 200 µL of 70% (vol/vol) ethanol (Wash buffer W4), and then dried at 60°C for 10 min. It was then resuspended in 50 µL of RNase-free water and store at -20°C.

3.4. NL63 Real-Time PCR

The human coronavirus (HCoV-NL63) real-time RT-PCR kit was used for the detection of human coronavirus NL63 (Biosb, Shanghai ZJ Bio-Tech Co., Ltd., China). The human coronavirus (HCoV-NL63) real-time RT-PCR kit contained a specific ready-to-use system for the detection of the HCoV-NL63 virus by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in the real-time PCR system. An external positive control (1 × 107 copies/mL) was used for the determination of the viral load. The PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for one minute.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Specific qualitative variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, whereas quantitative and numerical variables were analyzed using independent t-tests. Differences were considered significant at P values of less than 0.05.

4. Results

Out of 138 samples, 77 (55.8%) were from males and 61 (44.2%) from females. The average age was 33.66 ± 4.63 and 22.65 ± 3.23 for males and females, respectively. The youngest participant was a three-month-old infant with a respiratory infection (Table 1). Out of 138 patients with an upper respiratory infection, 33 (23.9%) were positive for coronavirus NL63, of which 21 (63.6%) were from males and 12 (36.4%) from females, with a male to female ratio of 1.75. The youngest infected participant was a four-month-old infant, and the oldest age was 72 months. The role of maternal antibodies in preventing infection has not yet been determined.

| Demographic Characteristics | Values | NL63 Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Male | 77 (55.8) | 21 (63.6) | 56 (53.3) |

| Female | 61 (44.2) | 12 (36.4) | 49 (46.7) |

| Mean of age | 27.54 ± 16.02 | 25.18 ± 18.433 | 28.29 ± 15.214 |

| Min age, mo | 3 | 4 | 60 |

| Max age, mo | 72 | 72 | 3 |

aValues are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

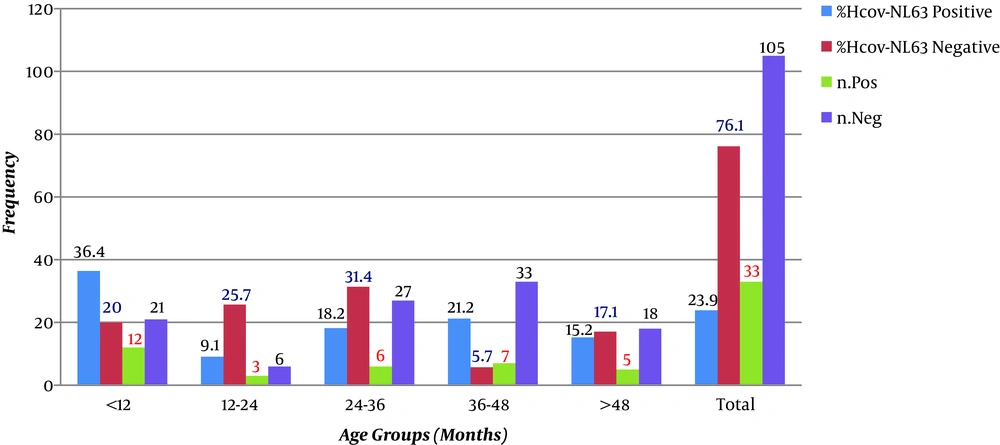

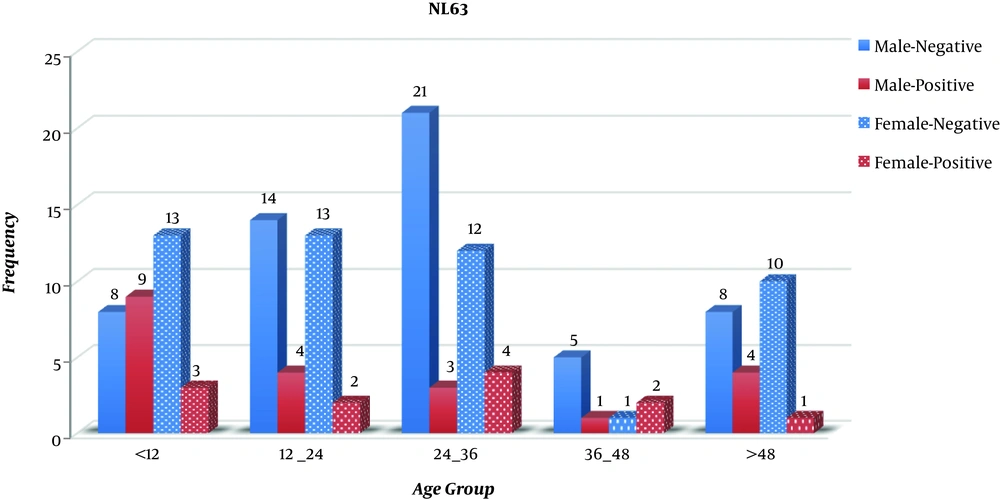

The statistical analysis showed no significant correlation between gender and positivity for coronavirus NL63 (P > 0.05). Clinical manifestations of all patients were noted in special forms. The frequency distributions of age and clinical symptoms are shown in Table 2. The highest incidence of acute respiratory infection (n = 40 patients; 29%) was in the age group of 24 to 36 months, and the lowest frequency (n = 9; 6.5%) was in the age group of 36 to 48 months. As shown in Table 2, out of 138 samples with an acute respiratory infection, the most common clinical symptoms were abdominal pain and wheezing (44.9%) and the lowest clinical symptoms were related to cough (29.0%). As shown in Figure 1, the most frequent age group was 24 - 36 months for males (17.39%) and 11.6% for females in age groups 24 - 36 months and less than 12 months. According to Figure 1, which evaluates positive cases for NL63 in different age groups, the age range of less than 12 months had the highest frequency (8.70%) and the age group of 36 - 48 months had the lowest frequency (2.17%). The results showed no significant relationship between age and NL63. According to Table 2, the most common clinical symptom in positive NL63 cases was diarrhea with a frequency of 97.0% and the least common symptom was nosing and abdominal pain with an incidence of 84.8%. The statistical analysis showed a significant relationship between clinical symptoms and NL63 positivity (P < 0.05). As shown in Figure 2, in males, the age group of less than 12 months had the highest frequency of NL63 infection (11.69%), followed by the age groups of 12 - 24 months and more than 48 months with the same frequency (6.19%). The lowest frequency (1.30%) belonged to the age group of 36 - 48 months. In female subjects, the age group of 24 - 36 had the highest frequency of NL63 infection (6.56%), followed by the two age groups of 24 - 12 and 36 - 48 months with the same frequency (3.27%). The lowest frequency (1.64%) was in the age group of more than 48 months.

| NL63 | Cough | Diarrhea | Nosing | Wheezing | Fever | Abdominal Pain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | |

| Negative | 96 (91.4) | 9 (8.6) | 88 (83.8) | 17 (16.2) | 76 (72.4) | 29 (27.6) | 74 (70.5) | 31 (29.5) | 75 (71.4) | 30 (28.6) | 71 (67.6) | 34 (32.4) |

| Positive | 2 (6.1) | 31 (93.9) | 1 (3.0) | 32 (97.0) | 5 (15.2) | 28 (84.8) | 2 (6.1) | 31 (93.9) | 3 (9.1) | 30 (90.9) | 5 (15.2) | 28 (84.8) |

| P value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||

aValues are expressed as No. (%).

5. Discussion

Preliminary data suggest that HCoV-NL63 may be an important viral pathogen and play an important role in the respiratory tract infection in children, similar to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and human metapneumovirus (hMPV). Therefore, in this study, we identified the HCoV-NL63 virus in children with an upper respiratory infection and evaluated the effect of HCoV-NL63 infection on children.

Coronavirus is one of the most important causes of upper respiratory tract infections and pneumonia in humans. Among them, HCoV-NL-63 is clinically important in young children (18). Thus, this study evaluated the frequency of this viral infection in children with respiratory infections in Kerman Province. Also, it examined the prevalence of HCoV-NL63 in different age and sex groups and its relationship with some clinical symptoms such as fever, cough, runny nose, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Out of 138 children under five-years-old without any chronic, genetic, or metabolic diseases with respiratory infections, 33 (23.9%) were positive for HCoV-NL-63 using real-time PCR. Viruses are the causes of about 80% of acute respiratory infections in humans. Acute respiratory infections (ARIs) are significant causes of deaths for 3.1 million people worldwide, especially children under the age of five years (19). Most deaths due to respiratory infections are related to infection in the lower respiratory tract system. The prevalence of this type of infection in children less than five years of age is estimated at 22% per year (20). The highest frequency (66%) of ARIs reported in Bangladesh was commonly due to RSV, parainfluenza virus, and adenovirus (21). Multiple studies have shown that one to 10% of the populations in Washington annually are infected with HCoV-NL63, which is an alpha coronavirus (22). Therefore, this virus is responsible for 10% of all respiratory diseases. Regardless of the geographical location, respiratory infections are among the three causes of death in children under five-years-old (23). This study, for the first time, was done to determine HCoV-NL63 virus infection in Kerman Province. Out of 138 samples from children under five-years-old with different clinical symptoms, HCoV-NL63 was detected in 23.9% of patients with an acute respiratory infection. The results showed a high prevalence of HCoV-NL63 in this geographic location. The mean age was 27.54 ± 16.02 months in the total sample and 25.18 ± 18.43 months in positive cases. There was a significant relationship between the decreased mean of age groups and the number of positive HCoV-NL63 cases. There were positive 12(8.70%) samples in the youngest age group (less than 12 months), while only 7 (5.07%) samples were positive in the age group of 24 to 36 months. The lowest frequency was in the age group of 36 - 48 months with three positive samples (2.17%). According to the results of this study, the high incidence and symptoms of this infection were in lower age groups that appeared to be at risk of severe HCoV-NL63 infection. In this study, the number of male patients was 1.75 times higher than that of female patients. The mean age of male and female patients was 33.76 ± 4.63 and 22.65 ± 3.23, respectively. According to the results, the sex of subjects in the studied groups was not correlated with HCoV-NL63 infection (P value > 0.05). In this study, the most common symptoms in infected individuals were diarrhea (32.9%), cough and wheezing (93.9%), fever (90.9%), and runny nose (28%). The gastrointestinal findings, including diarrhea, were the most common symptoms (97.0%). Respiratory infection with human HCoV-NL63 can develop the signs and symptoms of the respiratory tract and gastrointestinal symptoms. Therefore, the presence of this virus in digestive secretions indicates that digestive secretions can be one of the transmission routes of this virus (22). A study by Chany et al. (24) in 1982 reported short-term necrotizing enterocolitis in infants who had coronavirus infection. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea and the sudden outbreak of a disease in a large housing complex in Hong Kong showed that water and sewage could contribute to the transmission of the virus through the fecal-oral route (25, 26). In the present study, the clinical symptom “abdominal pain and nosing” in children with HCoV-NL63 was found in 28 (84.8%) patients. The results showed a significant relationship between clinical signs and positivity (P value < 0.05). The most common clinical symptoms were observed in the age group of less than 12 months. This indicates that maternal antibodies are not effective in preventing or controlling the infection. In a study by Kiyuka et al. (8) in Kenya on children younger than five-years-old, 5,573 samples of nasal discharge were collected, 1.3% of which were positive for HCoV-NL63 using real-time PCR.

In a study by Hand et al. (5) in Louisiana, USA, on nasopharyngeal specimens of 13 patients, HCoV-NL63 was positive in 54% of cases and rhinovirus in 15.42% of cases using real-time PCR. In another study by Zhang et al. in Guangzhou, South China, 1,3048 nasal and nasal discharge samples were collected from children and adults (from one day to 90 years) with the symptoms of fever and upper respiratory tract infections from July 2010 to June 2015. Coronavirus was detected in 294 (2.25%) samples including four coronaviruses OC43, 229E, NL63, and HKU. The frequency was 60.20% for OC43, 16.67% for 229E, 14.97% for NL63, and 7.82% for HKU. Coronavirus OC43 was the most frequent one. Also, in this study, the age groups of less than three years and more than 50 years were considered at risk of HCoV. In this study, the most common symptom was cough (83.33%) and the least frequency belonged to chest pain (1.36%) (22). More recently, Konca et al. (11) in Turkey reported the deaths of infants with lower respiratory disease. They isolated coronavirus NL63 from seven-month-old preterm infants. The HCoV-NL63 virus has been detected in countries around Iran. In a study conducted by Al Hajjar et al. (27) in Saudi Arabia in 2011, HMPV and HCoV-NL63 were found among children with upper and lower respiratory diseases in autumn and winter 2007 - 2008, with an estimated frequency of 8.3% for HMPV and 2.8% for HCoV-NL63. So far, a few studies have been done in Iran. In a study conducted by Madhi et al. (28) in Tehran, among 270 samples of patients admitted due to respiratory infections of different species, 0.58% were positive for coronavirus NL63. According to the results of this study and previous findings, coronavirus NL63 can cause mild to severe infections in children and adults, more frequently in men than in women. Also, coronaviruses can cause sudden death in premature newborns and infants. Mutations in the viral RNA polymerase gene, spike, recombination between the human, animal, and viral RNA genomes, mortality, and high rate of transmission of this virus from patients to the healthy population make coronaviruses more important.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, prospective population-based studies are needed to better understand the epidemiology and spectrum of HCoV-NL63 infection. Differences in the study populations could explain the observed changes in HCoV-NL63 infection in patients with underlying medical problems. These viruses often cause respiratory infections in young children and they can evolve and survive under environmental conditions and the host's immune response, so that they can infect other people. This study showed that the HCoV-NL63 virus causes respiratory infections with different symptoms and the it can cause to be hospitalized the children. Therefore, this virus, like other respiratory viruses in children, is important and should be considered.