1. Background

Since the end of November 2020, the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has spread to over 100 countries, affecting around 80,000 patients in China, with over 3,000 deaths (1). As the largest city in the southwest of China, Chongqing city is adjacent to the epicenter Wuhan City, which is at a high risk of COVID-19 outbreak. As of February 24, 2020, nearly 600 patients were confirmed with COVID-19, of which six Individuals died (2). In response to the COVID-19 epidemic, the Chongqing government launched the first-level reaction to this public health event on January 24, 2020. It took a series of strict prevention and control measures to prevent the spread of the epidemic (3). Some published papers showed that the parents of infants admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit are prone to anxiety and depression, which affected the family relations, and occasionally caused the conflicts between medical providers and parents (4-6). Furthermore, in the context of a disease epidemic, the adverse psychological reaction of patients and their family members might be exacerbated (7). During the outbreak of COVID-19, the parents of hospitalized neonates might experience greater psychological pressure than the general population, which may be due to their inability to accompany their children, uncertainty of the disease epidemic, and possible financial burden. However, few studies have investigated their psychological status and approach to relieve their psychological stress.

2. Objectives

Since our neonatal medical service providers focus not only on neonatal patients but also their families, we conducted this study to investigate the psychological status and the expectation of hospitalized newborns’ parents, and aims to provide tailored medical service and psychological support to the neonatal patients’ family.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

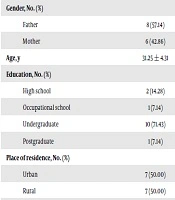

This study is a qualitative research. All parents whose infants were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit of Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University after implementation of the first-level response were all eligible for this study. The inclusion criteria were: (1) the infants staying in the hospital for more than three days; (2) infants having no severe diseases of heart, liver, kidney, and other vital organs; (3) parents being able to understand and cooperate with researchers fully; (4) informed consent was obtained from all parents. The parents with psychological disorders, speech problems, and audio-visual issues, or those who requested to leave the study were excluded. A purposeful sampling method was applied to select the subjects. The determination of sample size was dependent upon the repeated occurrence of respondents’ data and the fact that there is no new theme in data analysis, i.e., data saturation (8). According to the purpose of the study and the principle of the most significant difference in sampling, the parents in different administrative regions with various severity of the COVID-19 outbreak in Chongqing were selected (Table 1).

| Variable | No. |

|---|---|

| Parents (N = 14) | |

| Gender | |

| Father | 8 |

| Mother | 6 |

| Age, y | 31.25 ± 4.31 |

| Education | |

| High school | 2 |

| Occupational school | 1 |

| Undergraduate | 10 |

| Postgraduate | 1 |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 7 |

| Rural | 7 |

| Neonates (N = 14) | |

| Gestation age | |

| Term | 2 |

| Preterm | 12 |

| Birth weight, g | 2312.50 ± 807.15 |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Cesarean section | 9 |

| Vaginal delivery | 5 |

| One-child family | |

| Yes | 4 |

| No | 10 |

3.2. Data Collection

The phenomenological method was used in this qualitative study. A semi-structured interview outline was generated in advance based on published literature, and two experts’ consultation. The contents include (1) What impact does the current epidemic control have on you and your family’s daily life and psychology? (2) what problems did you face during your baby’s hospitalization? (3) What kind of help would you like from the medical service providers? (4) Do you know the corresponding protective preparation after discharge? The in-depth interviews were conducted in this study to assess the individual’s perspectives. One senior neonatal nurse specialist, who was familiar with the phenomenological method and had experience in the qualitative study, performed all the interviews. The same interviewer communicated with each interviewee once. All interviews were conducted in Mandarin of which the idioms and proverbs should be avoided as much as possible, and the information should be reiterated using regular language if the idioms or proverbs were present. To make sure the depth of the interview, the interviewer should listen to the interviewees’ statements carefully, guide and ask questions appropriately according to the interview outlines, and record the key points of the content and the changes of the interviewees’ mood and tone. The interviewees should not be interrupted during the interview unless they deviated the main subject of the communication. The interview would be ended once all content in the interview outline was fulfilled, and there is no any new themes with the general duration of 15 - 20 minutes.

Owing to the traffic control during the outbreak, it is not convenient for parents to communicate in the ward; thus, telephone interviewing was performed in this study. This study strictly follows the principle of informed consent and confidentiality and communicates with the interviewees before the interview. The researcher first introduces herself, introduces the research purpose, method, and content to the interviewees, and numbered the interviewee. To ensure the feasibility of the revised interview outline, three hospitalized newborns’ parents were selected for preliminary investigation before the formal interview.

3.3. Data Analysis

Within 24 hours after the interview, voice records were transcribed verbatim. The transcripts translated in English by a neonatal physician who was blind to this study (appreciated in acknowledgments). The transcripts were read several times to identify themes and categories by two researchers. Two researchers coded the transcripts line-by-line for the meaning of the sentences. Similar expressions were grouped; patterns of experiences were identified and labeled. After discussion, a coding frame was developed, and the transcripts coded. If new codes emerged, the coding frame was changed, and the transcripts were reread according to the new structure. This process was used to develop categories, which were then conceptualized into broad themes after further discussion. The specific steps are referred to as the phenomenological 7-step analysis method of Colaizzi (9): (1) carefully read all the data; (2) extract the statements of great significance; (3) code the recurring opinions; (4) collect the ideas after coding; (5) write the detailed descriptions without omission; (6) identified similar points of view; (7) return to the interviewees for confirmation.

3.4. Study Rigor

In order to ensure the validity and reduce the bias of this study, the same interviewer conducted all the interview, and the researchers who read the transcripts was not involved in the previous procedure. Final themes were established during the discussion with two experts who were experienced in the qualitative study and external to this study. The performance of this study adhered to the COREQ guideline (10).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

4. Results

The psychological needs of hospitalized newborns’ parents in the Chongqing area during the COVID-19 epidemic can be identified to 5 themes: urgent demand for timely up-to-date information of the children’s condition, need for psychological and emotional support, reducing the inconvenience caused by the epidemic outbreak, demand for protective information after discharge, demand for financial support.

4.1. Themes: Demand for Disease Information

During the epidemic outbreak, to avoid gathering, health care providers commonly took telephone communication with family about the children’s condition. Parents expressed their understanding but still want to get more information. In this study, nine parents expressed their willingness to get timely information updates on the newborn’s condition; three parents wanted to check the latest report of blood work or radiographic examination, two parents wanted to extend the communication time, indicating that the parents’ demand is variable.

4.1.1. Parents Could Not Fully Understand the Communication Content

“The doctor did tell us, but we are still confused. We cannot fully understand what lumbar puncture is. It sounded scary! (participant 6)”; “What was the screening of retinopathy of prematurity that doctors mentioned yesterday? Is it a routine for all babies? (participant 5)”.

4.1.2. Unsure About the Length of Hospital Stay

“How long will my child stay in the hospital? What is the criterion for discharge? (participant 7)”; “I do not know how long my child would stay. I hope he could be discharged earlier. However, during the COVID-19 epidemic, we think it might be much safer to stay in the hospital (participant 12)”.

4.1.3. Lack of Feeding-Associated Knowledge

“I did not know how long breast milk could be preserved after pumping. I used to pour redundant breast milk out frequently, but at present, I do not have enough breast milk (participant 3)”; “What kind of formula do I need to prepare for my child after his discharge? It is difficult to purchase formula amid the epidemic due to the closure of markets, could I get access to the formula supply from your hospital? (participant 8)”.

4.1.4. Insufficient Communication Time

“I hope I can talk with my doctor every other day or more frequently. I felt anxious yesterday because my doctor did not call me (participant 7)”; “I understand the doctors are very busy, is there any way for parents to contact doctors actively? (participant 14)”.

4.2. Themes: Demand for Psychological and Emotional Support

Owing to the restriction of parents’ visits to the NICU amid the COVID-19 outbreak, the parents could not be actively involved in the medical service that could increase the families’ psychological stress. The mothers are more likely to experience anxiety and depression due to the post-delivery dynamic changes of hormones; the COVID-19 outbreak could furtherly aggravate the psychological response.

“Mother’s mood was always volatile. I am very concerned about my daughter’s condition. She experienced mild asphyxia during delivery due to the insufficiency of amniotic fluid. Immediately after birth, she was admitted to the NICU, and I have never seen her since then (participant 1)”; “Now my wife still stay in the hospital, her condition is not very good. I always think that this coronavirus outbreak causes premature birth! Our family is worried about the baby’s condition (participant 4)”; “Now I do not concern anything other than my baby’s health. I have some extent of social isolation. (participant 7)”; “I am worried about my baby. He has been in the hospital for several days (participant 11).”

4.3. Themes: Reduce the Inconvenience Caused by the Epidemic Outbreak

As a result of the precautionary measures taken to contain the COVID-19 outbreak, all the parents in this study encountered some inconvenience in daily life and public transportation, some of which hindered the neonates’ access to urgent medical service.

“It is really inconvenient. There is no bus to Chongqing. If I want to drive private car, I have to get a certificate, but sometimes even I have a certificate, I am not allowed to drive into the city. The seal-off strategy of the city amid this period is very strict (participant 3)”; “We used to do some online shopping, but currently it took a much longer time to deliver the items (participant1)”; “My family lives in Changshou (a small town of the Chongqing metropolitan area). It is mandatory to check the certificate every time I drive up or down the highway. It is not easy for me to go to the hospital. I want some medical staff can help me to accompany my child to take some non-bedside examination, such as magnetic resonance imaging and endoscopy. Besides, we are going back to work position now. It may take one hour to come to Chongqing, we can ask for leave at an ordinary period. However, during this epidemic, it is hopeless to ask someone to take your shift (participant 8)”; “Now it is the COVID-19 outbreak, the traffic is inconvenient, everywhere is closed, and the medical insurance does not work (participant 9)”.

4.4. Themes: Demand for Protective Information After Discharge

During this research, ten parents revealed their limited information about the protective measures to be taken after their children’s discharge, and two parents said they knew part of the protective knowledge, but still confused about some details. All parents suggested the medical staff could carry out the pre-discharge teaching about the epidemic, which should be helpful for them to do discharge preparation. “During the outbreak, we purchased some face masks for my child but did not dare to use it. Currently, my baby is not breathing well, and I am not sure whether my baby should wear it or not? (participant 13)”; “I know I need to wear a face mask, and I have prepared disinfectant at home. I do not know what else I have to prepare (participant 12).”

4.5. Themes: Demand for Financial Support

In this research, two parents from rural areas demonstrated that they were suffering from the financial crisis. They hope the hospital or some facilities could provide some financial support. “My baby has stayed in the hospital for a long time, and the medical expenses have exceeded 100,000 RMB. Although I could get some extent of reimbursement from the insurance, the remaining is still a heavy burden for my family (participant 3).” “We have a twin; one is hospitalized in Chongqing, and the other in the local hospital. We are still struggling to solve the current financial crisis (participant 9).”

5. Discussion

This study identified five primary psychological needs of hospitalized newborn parents, which is helpful for the medical staff to deliver tailored medical services to each family.

5.1. Disease Information

The interview results showed that medical information about the children was still the most critical concern of parents under COVID-19. These data were inconsistent with the previous studies (11, 12), which revealed that in the regular period, enhanced confidence and reduced anxiety were the primary psychological needs. The underlying cause for this difference may be attributed to telephone communication during the epidemic, which could reduce the sense of intimacy and authenticity compared to face-to-face communication. Social isolation during the COVID-19 outbreak also made the parents’ understanding of their children’s condition more urgent. Therefore, medical staff should understand parents’ worries and expectations, and provide accurate and honest information about the infant’s condition, which is the primary task of communication and an effective measure to relieve their pressure. Besides, medical staff should be seriously aware of the parents’ demand and pay more attention to communication with the parents to improve their coping ability (13).

During the COVID-19 epidemic, medical staff can use network and multimedia technology to communicate with parents. Studies have shown that the family members’ satisfaction with the medical staff has increased significantly after the multimedia and network technologies being applied to assist doctor-patient communication and health education (14). Some hospitals have adopted cellphone APP and animation demonstrations to conduct doctor-patient communication and propaganda, opening up a new model of doctor-patient communication (15, 16). Therefore, we should provide multiple information support for admission education, communication during hospitalization, and post-discharge follow-up. Some techniques could be applied to convey relevant disease knowledge, such as display boards, publicity boards, publicity videos, WeChat official accounts, brochures, to reduce speculation and misinformation (17). As the first internet hospital platform in Chongqing, our hospital also opened the online consultation section of COVID-19, which can effectively spread the COVID-19 associated knowledge and relieve the parents’ anxiety.

5.2. Emotional Support

Under the COVID-19 outbreak, the parents’ visits are somewhat limited. Parents cannot have close contact with their infants. This seal-off mode of NICU, superimposed with the uncertainty of the current COVID-19 outbreak, may cause the parents to experience more negative emotions, including disappointment, fear, anxiety, depression, and helplessness (18). One study surveying 307 hospitalized newborn parents showed that 22.2% of the parents experienced anxiety, and 29.0% had depression (19). Our study indicated a similar result; most of the parents expressed anxiety during interviews. So it is essential to encourage the parents to express their inner feelings and understand their psychological demands. More emotional support should be provided amid the COVID-19 outbreak than usual. We took the following measures: Firstly, all newly admitted neonatal patients should be screened for the risk of COVID-19 according to family history. The infants with a high risk of the COVID-19 are admitted to the isolation room and the other infants to the ordinary ward. This action could ease parents’ concern about the risk of iatrogenic infection of the COVID-19. Secondly, pre-admission education for parents should be performed well. The medical providers comprehensively explain the knowledge about the COVID-19 and some associated issues which are of great concern to the parents. We also actively communicate with the parents about their mental condition to help them reduce detrimental emotions. Thirdly, based on doctor-parent communications, the nurse calls the parents daily to give them information about the newborn’s condition, including feeding volume, weight gain, urine output, stooling, activity, etc. The nurse also concerned about the parents’ emotional state, met the reasonable requirements of their parents as much as possible.

5.3. Social Support to Improve Convenience

Social support is the subjective and/or objective beneficial influence of various social relationships on individuals. Excellent social support can protect individuals from excess stress, which plays an essential role in maintaining good emotional experience (20). If the parents’ social support is not ideal, it is more likely for them to endure higher psychological pressure (21). This research showed that the strict control measures amid the COVID-19 outbreak caused much inconvenience to the daily life of parents. For example, it was inconvenient to purchase daily necessities for the infant, accompany their children, and pay medical bills. It was even inconvenient to buy some medicine after discharge and follow-up as outpatients.

Given the above problems, we actively provided some information about the internet hospital to the parents, to facilitate them to get access to the medical service at home. The following services can be performed online: (1) free online consultation on COVID-19; (2) communicating with doctors by pictures and text, enjoying one-on-one online communication with specialists. (3) on line prescription by doctors, and medication delivered to the home with free shipping; (4) quickly purchasing some daily necessities on the online supermarket affiliated to the hospitals, such as diapers, breast milk fortifier, which are also delivered to the home with free shipping.

5.4. Education of Protective Knowledge After Discharge

Our study showed that most parents got limited information about the protective measures for the newborns after discharge. At present, all kinds of propaganda media spread information about preventing children, adults, and the elderly from COVID-19 but seldom mention the precautionary measures for the newborns. Therefore, we urged the parents to make proper preparations for discharge. Before discharge, the charge nurse would give the parents a comprehensive and detailed discharge education. Meanwhile, some brochures about precautionary measures of the COVID-19 would be distributed to the parents (22). It is recommended to drive a private car to send infants back home. In addition, wearing masks properly and carrying sterile wipes are also suggested on the road.

5.5. Financial Support

Some rural parents said they were not allowed to work during the epidemic period, which exposes them to a substantial financial crisis. Purchasing some medication on the internet hospital and some daily necessities on the internet supermarkets could reduce the cost of transportation or accommodation for the parents from a rural area. During the neonatal patient’s hospitalization, the medical staff should take account of the medical expenses, and choose the appropriate treatment to reach a reasonable cost-to-benefit balance. The parents were also encouraged to add some insurance programs, and the low-income families could get various fund support if they met some criteria.

5.6. Limitations of the Study

Our study has some limitations. Owing to the characteristic of a qualitative study, each interviewee’s uniqueness and histories should be respected, so their specific experiences may not reflect the overall picture of psychological needs in China. Although telephone interviewing is a suitable approach for phenomenological research, it still has some drawbacks. The most obvious is its inability to develop and maintaining rapport through proper interview techniques, which is essential to facilitate the interviewees to present their private mental status (23). Furthermore, the subjects of this study only included mothers and fathers; other family members’ demand should also be investigated.

5.7. Conclusions

This study identified five primary psychological needs of hospitalized newborns parents under the COVID-19 outbreak. The medical staff should actively communicate with the parents, effectively provide emotional and financial support, reduce their inconvenience in daily life. Such support could be helpful to relieve the parents’ psychological stress.