1. Background

Cancer of children is a potentially life-threatening disease (1). The long process of treatment and dealing with such a crisis, make the cancer of a child a damaging experience for their families (2). In Iran, primary caregivers of children with cancer are their mothers, and studies indicated problems in different health domains of them (3, 4). To provide a family-centered care, nurses need to be familiar with the issues happening for the health of family members of children with cancer. Few studies exist in Iran, which examined the matters of health in mothers of these children. However, it is necessary to explore the health problems of caregivers of children with cancer, from a perspective, which helps nurses to get a diagnosis through their daily encounters and conversations with them. In our investigation, the qualitative methods of data gathering to reach nursing diagnoses are less documented in the literature on this issue.

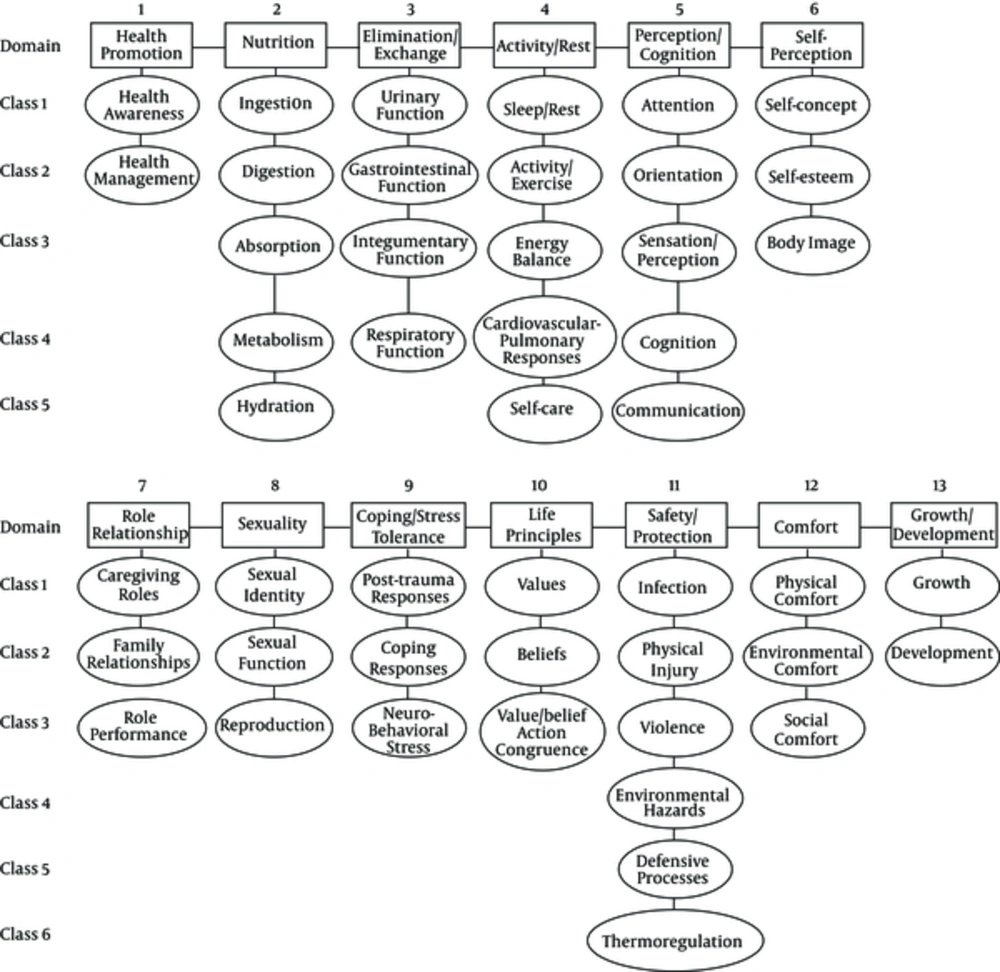

A nursing diagnosis is “a clinical judgment about an individual, a family or a community’s responses to actual or potential health problems/life processes”. The use of nursing diagnosis term is a method for unity of the nomenclature of common health problems in different domains (5). In 2002, North American nursing diagnosis association-international (NANDA I) developed a taxonomy to organize nursing diagnoses into different categories. The taxonomy has three levels: 13 domains, 47 classes (Figure 1), and 216 diagnoses (6). An appropriate assessment guides nurses to reach a proper nursing diagnosis. For every nursing diagnosis, there are defined subjective or objective characteristics, implying any deviation from normal in different domains of health (7). Listing problems through a comprehensive assessment, and comparing them with the defining characteristics of each nursing diagnosis leads nurses to a standard name for each health problem, which is a nursing diagnosis (6).

This study aimed to find nursing diagnoses for non-physical health problems of mothers of children with cancer through a directed qualitative content analysis of interviews with them.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

For this qualitative study, data collected from semi-structured interviews were analyzed using “directed (deductive) content analysis”. Qualitative content analysis includes a set of methods, which are used to analyze written texts of interviews. In directed content analysis, coding commences based on a theory or findings from a similar study (8), or it is used when the structure of analysis is operationalized on the basis of previous knowledge and the purpose of the study is theory testing (9). In this study NANDA I taxonomy was used as framework to categorize the codes.

2.2. Field and Population

The field included three pediatric teaching hospitals in Tehran, which had the highest rate of referral of children with cancer.

The study population included mothers of children with cancer who had inclusion criteria. Mothers recruited into the research had children whose cancer diagnosis was certain according to their oncologist, the diagnosis of childhood cancer was established at least 6 months ago and was not in its end stage. This study was a part of a phenomenological study to explore chronic sorrow in mothers of children with cancer. Sampling was continued until data saturation. This saturation occurred at participant number six, but two other interviews were also conducted. As the subcategories and categories were already determined and the aim of the present study was to examine a qualitative assessment to reach a nursing diagnosis rather to find more categories, this sample size seemed enough, according to some authors’ recommendations (9, 10).

2.3. Ethical Considerations

In the process of the study, in order to ensure adherence to the research ethics, procedures were monitored by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

2.4. Data Collection

In this study, the primary method of data collection was individual and face-to-face deep semi- structured interviews. Before any interview, the researcher first presented and introduced herself in the research environment, explained the nature and purpose of the study, identified appropriate participants and obtained the explicated consent of its provisions, and the time and place mutually agreed on and determined as desired and preferred by participants.

A total of 10 interviews were conducted in which two follow-up interviews were conducted with two participants in order to resolve ambiguities. An average duration of interviews was 45 to 60 minutes.

In order to increase the creditability and truthfulness of the data, confirmation of findings by participants, and also reviewing the codes by peers, were carried out (11).

2.5. Data Analysis

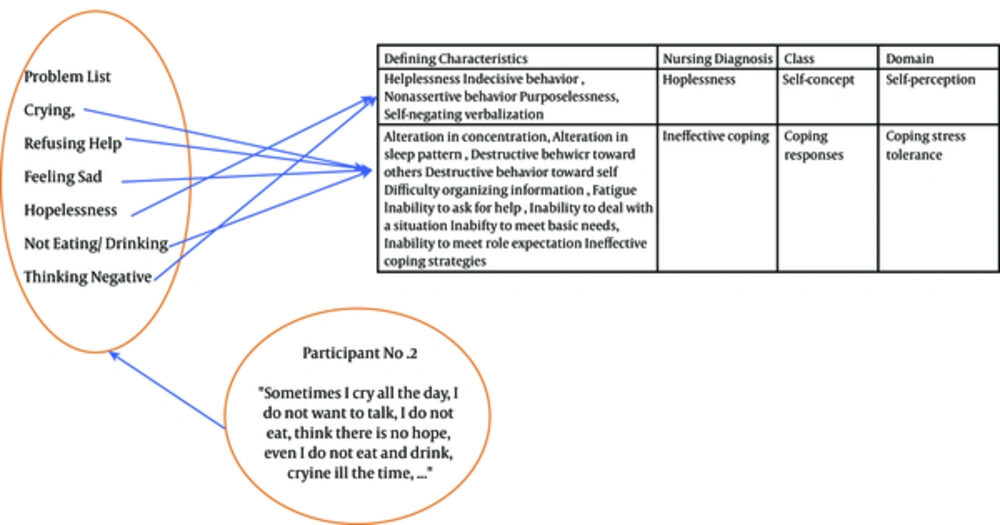

Data was analyzed using directed (deductive) qualitative content analysis. For this purpose, using priori coding (pre-set codes), the categories (some of domains of NANDA I taxonomy II), subcategories (some of classes of NANDA I taxonomy II), secondary codes (nursing diagnosis) and primary codes (defining characteristics) were already determined. A categorization matrix was developed and units of text were coded according to this categorization (Figure 2). The domains were “self-perception”, “role relationship”, “coping/ stress tolerance”, “life principles” and “perception/ cognition”. We did not include the other domains as they more imply physical matters, or are related to community or elderly people as nursing clients. Through a precise process of comparing, assigning and validating, problem list matched with defining characteristics to get a nursing diagnosis. The only nursing diagnoses that had units in the texts of all participants were included.

3. Results

In this study, eight mothers aged 27 to 48 years were interviewed. Other demographic characteristics of the mothers are given in Table 1. The data analysis resulted in a list of 125 meaning unit (health problems). Each of them matched with one defining characteristic of a nursing diagnosis, as primary codes, which were all classified in the following preset nursing diagnosis obtained from NANDA I taxonomy II and preset main categories (Table 2).

| Pariticipant No. | Demographic Characteristic |

|---|---|

| 1 | 27 y.o. Married. High school diploma. Housewife. Two children (6 y.o. Leuckemic since 2 years ago daughter and a 2 y.o. son). |

| 2 | 42 y.o. Married. High school diploma. Housewife. Two children (18 y.o. Leuckemic son since 4 years ago and a 14 y.o. son). |

| 3 | 32 y.o. Married. Baccalaureat of chemistry. Housewife. One 10 y.o. daughter with diagnosis of Wilms tomour since 1 year ago. |

| 4 | 34 y.o. Married. High school diploma. Housewife. Two children (8 y.o. Leuckemic son since 6 months ago and a 3 y.o. daughter). |

| 5 | 44 y.o. Married. Middle school graduated. Housewife. Two children (13 y.o. Leuckemic son since 3 years ago and a 8 y.o. son). |

| 6 | 36 y.o. Married. High school diploma. Housewife. One 8 y.o. Leuckemic son since 3 years ago. |

| 7 | 24 y.o.Married. High school diploma. Housewife. One 3 y.o. daughter with diagnosis of Rabdomyosarcoma since 2 years ago. |

| 8 | 48 y.o. Married. Master of Science degree in economy Working in private company. Three children (5, 8 and 11 y.o. sons. The older one with diagnosis of brain tumor since 1 year ago). |

| Domains (Main Categories) | Classes (Subcategories) | Nursing Diagnosis (Secondary Codes) | Some Of Defining Characteristics (Primary Codes) | Meaning Units (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Perception | Self-concept | Hopelessness | Expresses profound, overwhelming, sustained apathy in response to a situation perceived as impossible. | “I feel there is no hope for me” |

| Self-esteem | Situational low self-esteem | Helplessness, Indecisive behavior, Nonassertive behavior, Purposelessness, Self-negating verbalization | “I feel I am not a good mother for my other child anymore” | |

| Role relationship | Caregiving roles | Caregiver role strain | Apprehensiveness about future ability to provide care, physical problems such as headaches, Difficulty completing required tasks, Difficulty performing required tasks, Dysfunctional change in caregiving activities, Preoccupation with care routine | “I feel exhausted, I ask god to stop, my body, my soul are broken” |

| Family relationship | Interrupted family processes Readiness for enhanced family processes | Alteration in availability for affective responsiveness, Alteration in family conflict resolution, Alteration in family satisfaction, Alteration in intimacy, Alteration in participation for problem-solving, Assigned tasks change, Changes in relationship pattern, Decrease in available emotional support, Decrease in mutual support, Ineffective task completion | “It is more than one year we have not go to a party, life is not like the past for us” | |

| Role performance | Parental role conflict | Concern about change in parental role, Disruption in caregiver routines, Frustration, Guilt, Perceived inadequacy to provide for child’s needs (e.g., physical, emotional), Perceived loss of control over decisions relating to child, Reluctance to participate in usual caregiver activities | “I feel frustrated when I cannot help him or save him” | |

| Ineffective role performance | alteration in role perception, change in capacity to resume role, change in others’ perception of role, change in self-perception of role, change in usual pattern of responsibility, depression, discrimination, domestic violence, harassment, insufficient external support | “Sometimes I shout at my children, I do not want to, but I feel I cannot take all these responsibility” | ||

| Impaired social interaction | discomfort in social situations, dissatisfaction with social engagement (e.g., belonging, caring, interest, shared history), dysfunctional interaction with others, family reports change in interaction (e.g., style, pattern), impaired social functioning | “I ignore people in street, I don’t answer friends’ calls” | ||

| Coping stress tolerance | Coping responses | Ineffective coping | Alteration in concentration, alteration in sleep pattern, destructive behavior toward others, destructive behavior toward self, difficulty organizing information, fatigue, inability to ask for help, Inability to deal with a situation, Inability to meet basic needs, inability to meet role expectation, Ineffective coping strategies, insufficient access of social support, insufficient goal-directed | “Crying is the only one I do, day or night, I do not know what to do anymore” |

| Death anxiety | Negative thoughts related to death and dying, powerlessness, worried about the impact of one’s death on significant other | “The scene of my son’s death is always in front of my eyes, even if he is well” | ||

| Chronic sorrow | Feelings that interfere with well-being (e.g., personal, social), overwhelming negative feelings, Sadness (e.g., periodic, recurrent) | “When I am at home I forget everything, I am happy. The day I want to come for bone marrow or something else, I remember my sorrow” | ||

| Stress overload | Excessive stress, feeling of pressure, Impaired decision-making, impaired functioning, increase in anger, increase in anger behavior | “Sometimes I wish I could stop all these. It is more than what you could imagine” | ||

| Life principles | Values/ beliefs/ action congruency | Spiritual distress | questioning identity, questioning meaning of life, questioning meaning of suffering | “I wish someone comes to my dreams to say what was my sin that deserved me such a thing” |

| Readiness for enhanced religiosity | Expresses desire to enhance belief patterns used in the past, expresses desire to enhance connection with a religious leader, expresses desire to enhance forgiveness, expresses desire to enhance participation in religious experiences | “I have changed I want to go to Mashhad, the desire I never have had, I really feel I want to pray more” | ||

| Perception/ cognition | Cognition | Knowledge deficit | Expresses his lack of knowledge | “I did not have any idea about what this disease is, what is the bone marrow for, still I do not know much” |

| Readiness for enhanced knowledge | Expresses his desire to gain knowledge, asking questions, searching in resources | “I learned how to search in Internet about the diets for cancer, I really want to know more about its care” |

3.1. Perception/ Cognition

This domain has five classes (attention, orientation, cognition, sensation/ perception, communication), of which two nursing diagnosis, related to the class of cognition, were achieved based on the comparison of problem list of participants with defining characteristics of each of them. In the following, these two nursing diagnoses are explained:

3.1.1. Knowledge Deficit

Participants spoke often about their lack of knowledge of the disease and its treatment. This knowledge deficit was derived from the lack of pre-exposure to cancer and lack of interest in hearing anything associated with this disease. Mothers expressed that they obtained knowledge about cancer over time, after frequent hospitalization of their child. However, since these resources were not valid, they sometimes had doubts about its authenticity.

Participant No. 6 said: “When I just came here, I did not know anything about ALL and I just heard from others, I did not know anything about its name. After discharge, I slowly understood what it looked like. Now, I sometimes do not understand what is happening too. I asked others but they did not give me the right answer”.

Readiness for Enhanced Knowledge: most participants emphasized on their desire to learn more about various aspects of their child’s cancer.

Participant No. 5 said: “as I asked a lot of questions from nurses, they became angry, but we needed to know more. For example, what should we do during chemotherapy? What to do if they had fever at home? Specifically, I doubted whether going on diets was good for him or not. Well, who should we inquire from in such conditions? I wish we had a book”.

3.2. Self-Perception

This domain includes classes of self-concept and self-esteem. Nursing diagnoses of “Hopelessness” and “Low self-esteem, situational”, obtained in this domain are explained here:

3.2.1. Hopelessness

This is a diagnosis that was recognized for almost all participants and was a pervasive sense of hopelessness, which was often expressed verbally or non-verbally. They often felt hopeless about the future of their children. This diagnosis was more distinguished especially in mothers whose children had long course of treatment or had recurrence after the treatment.

Mother No. 6 said: “I was disappointed very much at the second relapse. Children who got transplant gave hope. Nevertheless, you see a few of them rejecting the transplantation. It is stressful. I always think about those who lost their kids, what they did in their house, I think about how bad they felt when they saw the child’s room empty”.

3.2.2. Situational Low Self-Esteem

Most participants stated that for various reasons they blamed themselves and had no good feeling about the following situations. Especially, they felt that others had a good life with healthy children, but as they had to endure hardships and difficulties caused by child cancer, it caused negative emotions in them. They heared statements such as “the disease of children is an atonement of parents” or that “maybe you are passing an exam” and this caused anger and hatred towards themselves and others.

3.3. Role Relationships

One of the domains that included many nursing diagnoses was role relationship. Cancer in children had created major changes in social health of mothers. Their relationships with their children, spouses, parents and other people were severely affected by the child’s disease. Nursing diagnoses obtained in this area included:

3.3.1. Ineffective Role Performance

Mothers stated that due to their child’s disease they could not provide optimal parental role on their other child or children. For example, participant No.2 said “I am overprotective of my sick son and this affects the other one, he has become nervous. When he realizes that I am focusing on the sick child, like when I give some fruit juice to him, he becomes so grumpy, I say to him you could make fruit juice by yourself or I say to him you could take the fruit by yourself. May be he prefers I take it to him”.

Participants emphasized on this point that their numerous other roles were affected by their caring role. For example, as a wife or a daughter, their roles have become ineffective which consequently have created problems for them. Participant No. 3 said “Now I feel so much sorrow for my mother. I am just a burden for them on their shoulders. Even for my husband I am not a good wife any more. I feel bored, and destroyed. I am bored of it”.

3.3.2. Interrupted Family Processes

More participants pointed out the changes in the psychosocial and spiritual family functions that led to ineffective solutions for family problems. Family routines were changed, and in general, life for the whole family was not what it was previously. Participant No. 8 said “Each of us lives in our own world. We do not talk together. I cry in my loneness. My husband also does it in a dark room, smoking. Our relative, who lives in our apartment, complains that when I am in the hospital, my husband does not eat and drink”.

Participant No. 6 said “No guests visit us. We never go anywhere. Even for the New Year celebration, no one stands up because we ourselves wish this. We are so exhausted to do what a normal family does”.

3.3.3. Parental Role Conflict

Mothers have to support their children, and at the same time sometimes see themselves in situations, which cause conflicts in the role of their mothering.

Participant No. 7 said: “Whenever I woke up the child for treatment, when I took him to the nurses, I suffered so much that it got to me. It is like you’re giving your child to death with your hands”.

3.3.4. Impaired Social Interaction

The participants spoke about their impaired social interactions that resulted in their child’s disease. Most of them refused to participate in social activities and did not like to see their family members.

Participant No. 6 said: “It became normal for family members, for example my mother stopped calling to ask about my son, because it has been a long time since I visited any one”.

3.4. Coping / Stress Tolerance

3.4.1. Ineffective Individual Coping

Mothers participating in the study pointed out on the use of several coping strategies of which most of them were emotion based. These methods included positive thinking, resorting to religion, talking with others, and trying to be optimistic. These methods led to an effective coping when the process of the disease was stable and the mother did not feel threatened. Due to the uncertainty and fluctuations of the process of cancer, despite the use of coping strategies, effective coping in most of the mothers did not occur.

Participant No. 4 said “We neither slept nor ate, I am always anxious to come to the hospital and hear bad news. Since my child has been sick, I have had headache and backache and thousands of other pains. My bag is full of pills which I always use to be calm”.

3.4.2. Death Anxiety

On the other hand, fear of child’s death was a continuous and constant feeling that in certain situations, it escalated and in some participants, obsessive thoughts about the child’s funeral and mourning ceremonies were developed which made the mothers to be very distressed.

Participant No. 1 said: “Whenever you come here and see one of the children has died, a few days your mind would be occupied. I am of the opinion that cancer means that you should forget any happy moment and always think about your child dying”.

3.4.3. Chronic Sorrow

Recurrence sorrow like it had happened at the time of diagnosis or sometimes even worse than it, was a phenomenon which most of mothers mentioned. In fact, episodic grief and fluctuations of mourning occurred in mothers and prevented them from having full adaptation with the disease.

Participant No. 7 said: “I think relapses made us to suffer more than the first confrontation with the disease, I saw mothers who cried and bewailed even more than the time of diagnosis. Every time I came to take the test results, or any time the child had a fever, or it was necessary to have a check-up, the distresses began!”

Stress Overload: Participants express high levels of stress they should tolerate every day and the fact that this stress level was more than they could tolerate.

Participant No. 4 said. “Now I am so nervous, in one or two other cases in my life I had such a feeling, I say to God: God, God, why, and God does not reply, I say to God! I’m tired. Leave me alone! You see me, my shoulders are flat and you allow my shoulders to be burdened. Enough! It is not possible to tolerate anymore”.

3.5. Values and Beliefs

This functional health pattern in the participants includes subcategories of spiritual distress and readiness to promote religiosity.

3.5.1. Spiritual Distress

Mothers mentioned their spiritual and philosophical challenges frequently after disease came to their life, and this subcategory had the most frequent semantic codes among other subcategories. In fact, religious and spiritual questions, including why their child had this disease, and whether they were being punished or they were chosen as one who was being forgiven by this event, occupied the minds of all participants.

Participant No. 8 said: “I sleep at night with the hope that one would come and tell me why I deserve this”.

Participant No. 5 said: “I said to God that He considered the hardest exam for me. Why me and not another person? I do not know. Sometimes I think I’m mentally very involved in all of this if all of them were actually nothing”.

3.5.2. Readiness for Enhance, Religiosity

Participants who had many spiritual questions and were challenged with spiritual matters also expressed how they got close to God after their child’s condition. A great desire for religious practices such as avow, praying, resorting to Imams etc., were used as methods of self-soothing. This good feeling caused by religious resort was temporary and with disease’s exacerbations, fear and grief replaced it.

Participant No. 4 said “A faithful servant helped us to learn many Quran prayers. She did not read any prayers out of Quran. Only Qurans verses. I get up 4 in the morning; I read lots of Quran prayers on the road to the hospital”.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study indicated that through a qualitative encounter with a client, it is possible to detect health problems in different domains and label them as nursing diagnoses. Mothers of children with cancer in Iran may improve many health problems in different health domains, which need to be considered in the care plan of their children.

“Knowledge deficit” about the disease is one of the matters for parents of children with cancer. This means lack of information about the disease’s process, treatment and its prognosis, related to the lack of previous exposure, lack of interest in learning about this issue, cognitive disability or lack of familiarity with sources of information about the subject (6). In the case of the mothers participating in this study, lack of previous exposure and lack of familiarity with information sources were the main reasons for their knowledge deficit. This is confirmed the results of another study, in which participants frequently mentioned their knowledge deficit about the disease as the most important factor in their inability to make decisions (12). In a qualitative study in Iran, inadequate knowledge was one of the themes extracted from the interviews with mothers of children with cancer (13). However, in this study, mothers expressed their desire to increase the level of knowledge about cancer and its treatment. Health-seeking behaviors are one of the themes in the study of Renner and McGill (2016) with the aim of exploring factors influencing health-seeking decisions and retention in childhood cancer’s treatment programs. They believed that knowledge deficit is one of the important related factors and non-professional approaches may lead to mistreatment (14). When the patient and his family showed interest to have knowledge and expressed their own knowledge deficit, nurses mentioned diagnosis of “readiness to increase knowledge”, then educational planning for determining different goals in psychomotor, cognitive and emotional domains was necessary (6).

Nursing diagnosis “hopelessness” is defined as a state of mind in which the personal choices are limited and there is no escape of a situation, and there is no energy of its own. This situation can occur in patients with multiple symptoms. Among them, isolation, negative statements about the future, fatigue and lack of interest, the feeling of being abandoned, etc. can be mentioned (6). Other studies also reported hopelessness of parents, especially mothers of children with cancer (15-17). Despite existing available tools for discovering hopelessness (18), it can be discovered through daily communication with the parents of a child with cancer, by their expressing negative feelings about what would be happen in the future for their child. It has been shown that social support can cause less disappointment and hopelessness. This is confirmed in the present study. Active encouragement of parents to take advantage of social support networks and their financial support, positively affected their level of frustration and hopelessness (16).

“Situational low self-esteem” means expressing negative feelings about themselves, due to the current situation, is one of the factors affecting the mental health of parents of children with cancer. Verbal expression of negative feelings about themselves and the challenge of finding the causes of negative events were the major features of this nursing diagnosis (6). In parents of children with cancer, low self-esteem occurs after several times of their inability to control the situation and they feel that compared to others, they are surrounded by misery (19). In another study, it is considered as one of the late psychological effects of cancer of child on parents (20). As hopelessness is an obstacle for optimism and coping of parents, it is crucial to be found in parents of children with cancer and managed as a part of a family centered care (21).

“Stress overload” was one of the other nursing diagnoses for mothers who participated in the study, which means high number of requests by mothers that were required to be answered. Verbal expression of lots of stress and physical, mental, cognitive and behavioral reactions associated with the disease of the child were signs and symptoms of this nursing diagnosis, which was obtained from the interviews of this study. Constantly trying to adopt with very hard conditions of cancer, the matters arising from burden of caring, commuting from remote areas to hospitals, and financial issues arising from the existence of a chronic illness, were among the related factors cited for this diagnosis which was also observed in our study. Considerable were the feelings of loneliness of mothers in the care of child caused by dissuasion of father for various reasons. Some of them eliminated their husbands from the treatment process in order to protect them, while in the others, the husbands themselves resigned on their own. This increased the effect of stress on the mothers (22). High levels of stress in mothers of children with cancer have been noted in other studies (23) and this stress can have a negative impact on parents’ adjustment to chronic illness and cancer, and this directly affects the quality of life of children (24).

“Ineffective role performance” and “role conflict” were among the problems seen in mothers of children with cancer in this study. Ineffective role performance means behavioral patterns, which, are not matched with expectations and norms, with features like uncertainty, burden of care, ineffective coping with the situation and expressed anxiety. In fact, individual believes in his inability to perform his roles, or others see his behavioral patterns as indicative of ineffective role performance. Inadequate supports, limited resources, unrealistic expectations from themselves, knowledge deficit and ineffective communication with the health care providers, are some related factors to this diagnosis (6). In our study, mothers frequently expressed their dissatisfaction in playing their multiple roles, including social, marital, and parental and mentioned their focuses on the burden of care, frequent staying in the hospital and lack of supportive and helpful partners, as the main reasons. Other studies also mentioned intensifying parental role for sick children and its adverse effects on other roles (25-27). After the diagnosis of children with cancer, their mothers are confronted with new roles, which include a commitment to physical proximity with the child to ensure 24 hours care and providing his comfort. This causes fundamental changes in their other roles and social functions, especially the role of the parents to other children (28).

Studies have also supported the result of the recent study about “ineffective social interactions” and “social isolation” of mothers of children with cancer (27-29). In other studies, the loss of employment opportunities and reduced income of mothers of children with cancer are mentioned (30), but these were not mentioned in our study by mothers. Although social isolation, withdrawal from others and lack of utilization of community resources and support of relatives and friends were the matters mentioned in our research which support the results of other studies (22, 31). It seems that nurses should care about problems of parents especially mothers and encourage them for effective interaction with the community and enjoying from the positive effects of social support systems (31).

“Altered family process” means changes in family relationships and functions, which are characterized by the lack of appropriate reactions of family to the crisis. This would cause not meeting the needs of each member of family, and it is related to factors such as an interruption in routines of family due to illness, changes in psychological state of family members due to child’s illness, the financial burden put on the family and frequent hospitalizations of child (6). In this study, the mothers reported that their family routines were greatly affected by their child’s condition. This study supports the results of other similar studies (32).

Fatigue, impaired social interaction, lack of use of social support systems, exhibiting behaviors, which inhibit adaptation, expressing worries and chronic anxiety were the matters, which were repeatedly reported in the interviews by participants and are the characteristics of the nursing diagnosis “ineffective coping”. In this situation the person does not use effective methods to cope with the situation (6). Mothers participating in our study used the emotion-focused coping strategies such as resorting to religion, optimism, positive thinking and trying to have positive thoughts of which the findings are consistent with the results of other studies (33, 34), but in the end the presence of a lot of symptoms, such as crying, social isolation, and ineffective family relationships showed failed adaptation. On the other hand, occurrence of psychological issues including death anxiety and chronic sorrow were factors, which affected ineffective coping of mothers. Participating mothers frequently expressed the obsession over the death of child, which is consistent with the results of other studies (35, 36). Chronic sorrow or episodic presence of behaviors like worriedness and sadness, concern and discomfort at the time of some events like a death of another child in hospital or cancer recurrence in their own child, are what most of mothers of children with cancer experience (37).

Spiritual well-being is one of the aspects of health, which can be threatened by several factors such as one’s own or a close relative’s illness. Spiritual distress is one of the nursing diagnoses characterized by inability in making meaning out of life by simply connecting to a particular endless power. Several questions about the cause of death and illness, frustration, feelings of being empty, inability to feel the joy of life and recent interest in spiritual issues and questions are recognized as features of this diagnosis (6) which were also seen in the mothers in our study. Fear of reprisal of God for sins, the belief that children disease was the atonement of parents’ sin and feeling of the wrath of God were the cases, which were observed in this study. This originated from the religious beliefs of Iranians. Due to cultural reasons, women were faced with many spiritual and religious challenges. Although by appealing to religion and spirituality and ceremonies and religious rites like vow and repentance, they tried to adopt positively with the disease but in bereavement crises arising from fluctuation of the disease, feelings of hopelessness and helplessness were experienced. Results of other studies also emphasize that the role of spirituality and religious issues highlighted in the parents dealt with their child’s cancer (22, 38, 39). Spirituality acts as a positive factor for compatibility of child and her family with cancer (40). So that spiritual distress is a cause for anxiety and maladaptive behaviors (41). Since the role of religion is so important in Iranian culture, and several studies indicate high incidence of religious and spiritual challenges in cancer patients or their families (17, 42, 43), familiarity of nurses with this nursing diagnosis and necessary interventions to change the spiritual insight of mothers of children with cancer is essential. This is more considerable when all mothers emphasize on the presence of spirituality as a positive factor for adaptation with cancer of their children.

4.1. Conclusion

This study explored the health problems in different health domains in mothers of children with cancer through a qualitative approach of assessment. Concerning children with cancer, physical, psychological, social and spiritual health of mothers directly affects the health and quality of life of their children. One of the requirements of family-centered and holistic care for children with cancer is to assess the health status of family members, especially the primary caregiver of the child. The results of this study can give oncology nurses an insight into the problems of different domains of health of mothers of children with cancer through their daily conversations. Since the integration of family-centered care to conventional care is one of the strategic objectives for children with cancer in Iran, the results of this study can meet the needs of planner’s attitude about psychological, social and spiritual problems of mothers of children with cancer. Establishment of care protocols of non-physical problems without having information about the issues those mothers of children with cancer experience in these areas, is not possible. Therefore, although participants in this study were all selected from teaching hospitals and among the medium and low socioeconomic levels, which were the limitations of the study, the results of this study can open a window towards obtaining consciousness and attitudes about the overall needs of families of children with cancer. As the only nursing diagnoses with existing definitive characteristics in all participants were included, many other nursing diagnoses (representative of other health problems in mothers of children with cancer) were ignored.