1. Background

Atrial septal defect (ASD) is currently one of the most common congenital heart diseases (CHD) with a higher incidence in females (1, 2). Right ventricle volume overload, pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmia and paradoxical emboli can be serious sequel of an unrepaired ASD, especially in the older ages (3). The first surgical closure of ASD was performed by Murray et al in 1948. Later on, King and Mills could successfully innovate the transcatheter closure in 1976 (4, 5). Whenever it can be applicable, this method is much preferred due to its excellent results and fewer complications. The success rate of transcatheter closure is affected by accurate sizing of the defect and its rims (6, 7). Different types of echocardiography (transthoracic, transoesophageal or intracardiac) as well as balloon sizing (BS) may be used for defect measurement (8). BS measures the size of ASD in a stretched round form, created by a near zero pressure balloon. However, it has been criticized as it increases the costs, procedure time, and complication rates (9). Echocardiography can show the unstretched defect size as well as its anatomy. The mostly used method is transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Meanwhile, intracardiac echocardiography can provide excellent views and also can be used successfully even without BS for the closure of ASD (10). In some reports, inexpensive transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has been accredited for defect assessment (11).

2. Objectives

To offer new insight, this study has been conducted to compare the success rate of ASD device closure between patients for whom defect size was measured by TTE only, and those for whom BS was also performed.

3. Methods

This hospital-based, combined retrospective and prospective study was performed from March 2014 to March 2018, at a single center.

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

All children aged ≥ 2 years old who had secondary ASD with at least a shunt ratio of 1.5/1 were enrolled.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients with multiple defects, sinus venous or primary defect, pulmonary hypertension, and inadequate rim of inferior or superior vena cava were excluded.

3.3. Data Collection Process

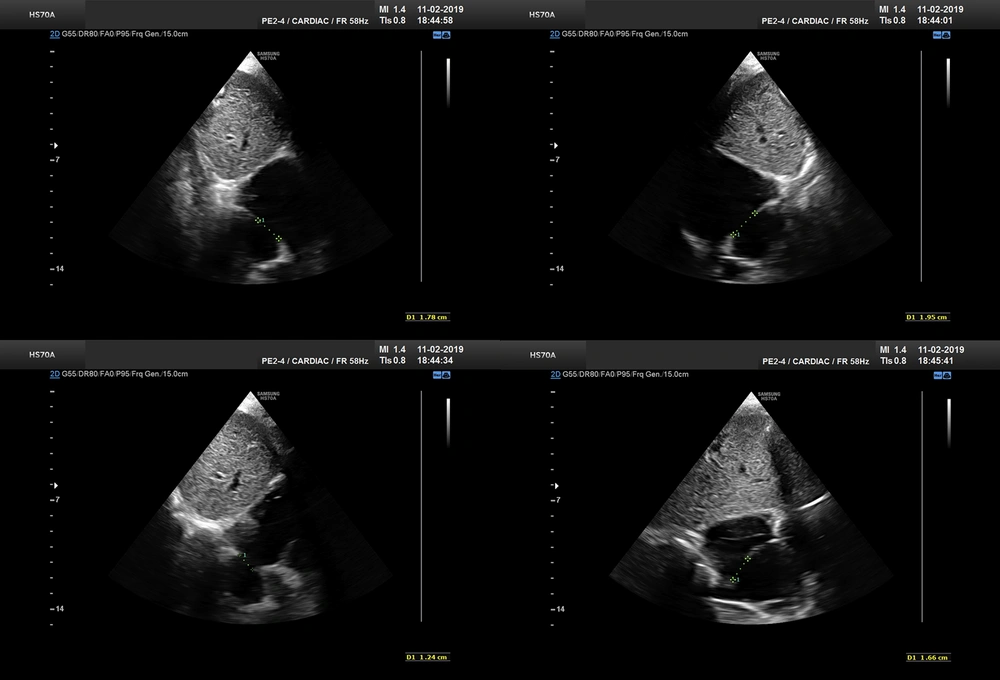

As study group, we included all patients meeting our criteria. Since BS became out of date, we replaced our TEE machine. Ascontrol group, we selected an approximate number of our latest patients treated with BS under TTE, to minimize any effect of learning bias. The closure method and techniques were similar as previously reported (12). We measured defect size and its rims on substernal view by putting the probe at 12, 1:30, 3, and 4:30 o’clock positions (Figure 1). If the view of 1:30 o’clock was suboptimal, we substituted 1:00 o’clock view. The largest measurement among the four values was considered as the largest ASD diameter. As we previously showed, BS yielded in average a 20% increase to the largest defect diameter (12), and considering some overestimation by BS, we have chosen the device size by adding 15% to the largest measured size. This value was the final device size or the nearest upscaled number available. We used the stopped-flow technique for BS.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

We used SPSS software, version 22 (SPSS Institute, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). All experimental values are presented as means ± standard deviation or frequency. Independent t test was used for comparisons between groups. Undesired effects were analyzed by the chi-square crosstab. P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We also performed a subgroup analysis based on age, weight, gender, and defect size.

4. Results

Eighty-eight children with a mean age of 6.48 ± 3.32 (range 2 to 15) years were enrolled in this study. The majority were females (53 versus 35 patients). Their weight ranged from 7 to 57 kg (mean: 21 ± 9.63). The Occlutech Septal Occluder (Occlutech GmbH, Sweden) was the most common device used (82 patients) followed by Nit-Occlud ASD-R (pfm AG, Germany; 3 patients), Cera ASD Occluder (Lifetech Scientific, China; 1 patient), Memoprat ASD Occluder (Lepu Medical, China; 1 patient) and Amplatzer Septal Occluder (Abbott Laboratories, USA; 1 patient).

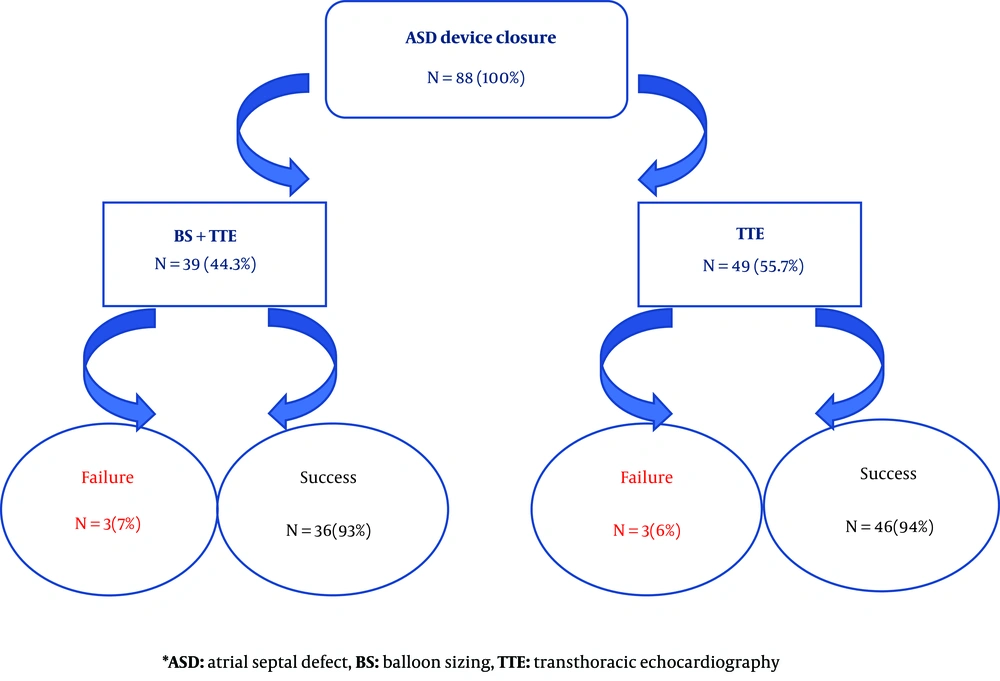

The size of ASD was measured by both BS and TTE in 39 (44%) patients while in 49 (56%) patients only TTE was performed. The ASD device closure was failed in 6 patients (6.8%, 3 patients in each group) due to device prolapse into the right atrium. They were referred for surgical ASD closure. The mean size of the defect was 12.3 ± 4.81 millimeter in BS group and 13.4 ± 3.63 millimeter in the only TTE group and the difference was not significant (P-value 0.221). The mean size of the device was 17.3 ± 6.22 millimeter in BS group and 15.2 ± 4.5 millimeter in the only echocardiography group and again, the difference was not significant (P-value 0.343).

BS didn’t change the success rate of ASD closure (93% with BS versus 94% without it, (P-value 0.573) (Figure 2). The mean size of the defect was 20.33 millimeter in patients with failed procedure compared to 15.72 millimeter with successful procedure, and it was statistically significant (P-value = 0.012). We revealed that there was not any significant difference between the success rate of ASD device closure and the age (≤ 6 versus 6 years old), weight (≤ 20 versus 20 kg) and gender of the patients (Table 1).

| Variable | Patients with Successful Closure (%) | Patients with Failed Closure (%) | Total Patients (N) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.890 | |||

| Female | 49 (92.5) | 4 (7.5) | 53 | |

| Male | 33 (94) | 2 (6) | 35 | |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤ 6 | 43 (95.5) | 2 (4.5) | 45 | 0.868 |

| > 6 | 39 (91) | 4 (9) | 43 | |

| Weight, kg | ||||

| ≤ 20 | 45 (96) | 2 (4) | 47 | 0.234 |

| > 20 | 37 (90) | 4 (10) | 41 |

5. Discussion

The ASD device closure with inaccurate sizing can result in undesirable complications, including embolization and erosion (13). Although undersizing is associated with residual leaks and embolization, oversizing can bring about arrhythmia, device distortion and aortic root erosion (13, 14). Over the past decades, the ASD device closure with BS had been popular; however, it often overestimated the size through overstretching the defect (15). Generally, a device identical or 1 - 2 millimeter larger than the stretched balloon diameter was implanted (16). On top of defect oversizing, BS often led to septal tearing, additional costs, prolonging fluoroscopy time and inevitable excess irradiation exposure. Hence, it has been gradually omitted from the routine ASD device closure (17-19). The current study indicated that the success rate of ASD device closure didn’t change by BS.

Recently, majority of pediatric cardiac interventionists prefer transcatheter ASD device closure without BS techniques. Gupta et al compared the success rate between BS and TEE (device size = largest diameter from 4 measurements, or average if the difference was more than 6 millimeter) and concluded that the success rate was higher in group without BS (90% vs 67%) (20). Arora et al. (21) reported their result of ASD closure only by TTE sizing and guiding (device size = largest defect size or up to 2 mm larger). In 3.6% of their patients, the device was embolized within 12 hours after the procedure. Vijarnsorn et al. (17) showed that BS was associated with neither oversizing nor better success. Patients who underwent BS had lower device/defect ratio (1.22 vs 1.31, respectively). Bartakian et al. (22) compared BSS (stopped-flow technique) to TTE measurement (device size = 1.2 × average of three views) and reported similar success rate. Zanchetta et al. assessed the defect size using intracardiac echocardiography and could firstly define the specific formula for size of the defect as r=√(C2 + P2) in which r, C and P represented for device size, foci half-distance of the fossa ovalis and semi-latus rectum, respectively. They could also determine the equation of d=√(a × b) in another study in which d, a and b represented the diameter of the device, major axes of intracardiac echocardiography on aortic and four-chamber plane, respectively (23, 24).

Totally, most reports used either the largest or average diameter in different views, with acceptable results in both approaches. An addition of 15% - 20% to the measured defect size by echocardiography was preferred by most, and yielded better results.

Two-dimensional, transoesophageal, intracardiac, and three-dimensional echocardiography has been used and recommended for ASD sizing (19, 20, 25). Pan et al. (26) indicated that ASD device closure can be performed under two-dimensional echocardiography, without TTE or fluoroscopy. They also demonstrated that TEE is useful for those with poor echo window.

Erdem et al. (27) emphasized high safety and efficacy of TTE in ASD device closure. They studied 206 patients under TTE compared to the 131 patients with TEE. They concluded that TTE as a faster method provides clear acoustic views and more patient’s comfort (27).

The study by Baruteau et al. (28) compared ASD closure with BS measurement under TTE guiding to TEE. Although those under TTE had larger defects and more deficient rims, the success rate under TTE was higher.

Our studies denied any relationship between patients' weight, age and gender with the successful procedure. However, the rate of failure was noticeably higher in the larger defect. Rastogi et al. (29) reported that patient’s weight, defect diameter, device size, aortic rim and device/defect ratio played effective role in increasing the success rate of ASD device closure.

5.1. Limitations

The study was mostly retrospective. The number of patients whose defects were closed without BS under TTE was limited. Despite these limitations, we found acceptable results.

5.2. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that device size selection based on only TTE measurements can provide acceptable results, and adding BS is not necessary for simple ASD closure.