1. Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder whose symptoms appear in early childhood. It is usually detectable by age 3, but for some reasons, it may not be diagnosed until pre-school age (1). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) organization (2016), 1 out of 54 children had autism, and the prevalence of the disorder is increasing (1-4). According to the diagnostic criteria in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (5), the symptoms of this disorder include impaired communication and social interactions, repetitive patterns of behavior or interests, and limited activities. Although these symptoms begin early, autism may not be diagnosed for a while (2, 3, 5). The symptoms of this disorder are varied in severity and mildness from one to another (2, 6).

The disorder may affect all areas of occupational performance, including social participation, play, sleep, activities of daily living (ADL), education, performance patterns, executive functions, functional skills, and personal factors (6-9). Children with ASD also have impairments in developing the theory of mind (ToM) (3, 5, 10). ToM is the ability to interpret the mental states of oneself and others to understand, explain, predict, and manipulate others’ behavior, enabling people to understand their own and others’ mental states (8, 11, 12). Play is an integral part of children’s daily life and an indicator of their developmental process. Problems in play can indicate defects in the child’s physical, cognitive, and social development (13, 14). Children with ASD usually have defects in playfulness (3, 15). Therefore, interventions have been defined to improve pretend play. Studies have shown that ToM is related to pretend play (3, 5, 8, 12), but the aspects of this relationship are unclear.

Various studies have examined the relationship between ToM and pretend play (3, 15-17), but so far, the relationship between different levels of ToM and the quality of pretend play has not been studied. Given the main concerns in social communication in children with ASD, it is crucial to discover the causes and factors that effectively improve this problem (which is the main symptom of ASD).

2. Objectives

In the present study, the relationship between different levels of ToM and the quality of pretend play was compared in children with autism aged 5 to 7 years with their typical peers. We hypothesized that children with higher pretend play skills have better scores in ToM.

3. Methods

The present study was a case-control observational design. The target population included typical children (control group) and ASD children (case group) aged 5 to 7 years old. ASD children were included in the study by the convenience sampling method, and typical children were selected by cluster sampling. The sample size in the case group was estimated at 18 and, in the control group, was determined to be 45, according to the study by Chan et al. (3). Sampling was performed in the Research Center for Developmental Disorders of Children, kindergartens, and typical schools of Hamedan Province, and the participants were homogeneous in terms of gender for the 2 groups. Inclusion criteria for ASD children were receiving a diagnosis of ASD from a psychiatrist and obtaining a score of 30 to 36 on the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale (GARS-2) test that indicates high-functioning autism (15, 16). For typically developed children, a report from their parents or teachers was required. This report consisted of parents’ and teachers’ claims of no neurological disturbances, no developmental delays, and no vision, hearing, or language problems. If children had any of the mentioned situations and problems, they would have been excluded from the study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1399.555; ethics.research.ac.ir/EthicsProposalView.php?id=151669).

The questionnaires used in this study were the GARS-2 test, the Persian version of the ToM test, and the child-initiated pretend play assessment (ChIPPA) test. Children performed both tests of ChIPPA and ToM, and the examiner rated the individual’s performance.

3.1. Questionnaire of the Persian Version of the ToM Test

The main form of this test has been designed for children aged 5 to 12 years old and administered as an interview with children. Ghamarani et al. showed that this test had satisfactory psychometric properties for use in Iran (18). In this test, the examiner shows pictures to the child and asks questions. The correct answer score is 1, and the wrong answer score is 0. The total score of the test varies from 0 to 38 and is divided into subscales as follows: (1) the first subscale (the first level of ToM): A numerical score between 0 and 20; (2) the second subscale (the second level of ToM): A numerical score between 0 and 13; and (3) the third subscale (the third level of ToM): A numerical score between 0 and 5. Higher scores indicate better performances of the child.

3.2. ChIPPA

It is a standard test designed for children aged 3 to 8 years old and has good validity and reliability (19). To use this test in children aged 5 to 7 years, the test is held for 30 minutes in 2 general categories of symbolic plays and conventional imaginary plays, in which a set of 2 scores in each subscale provides the total score of pretend play. In each general category, 3 principal scores are obtained from the child’s play: Percentage of elaborate pretend actions (PEPA) by the child, number of imitated actions (NIA) by the child, and number of object substitutions (NOS) by the child (20). Higher scores on PEPA and NOS and lower scores on NIA indicate better performances.

3.3. GARS-2 Test

The GARS-2 test is a diagnostic scale of autism developed by Gilliam in 1994. This test has 4 subscales: Stereotyped behaviors, communication, social interaction, and developmental disorders. Each scale includes questions related to that section, which can be used for the age range of 3 to 22 years. This test can be completed and scored by a therapist or parent at home or school. The validity and reliability of this test were confirmed in a previous study (21). Higher scores on this test indicate greater severity of autism symptoms. Scores below 30 exclude the diagnosis of autism, scores between 30 and 36 indicate mild to moderate autism, and scores between 36 and 60 indicate severe autism.

To interpret the data, first, the normality of data distribution was checked by the Shapiro-Wilk test. Then, in normal data, groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey post hoc test, and abnormal data were compared by the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Also, independent sample t-test was used where two groups comparison was needed. Finally, the Pearson correlation test was used to determine the relationship between comparethe play and ToM scores. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 20 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA) at a significance level of 0.05.

4. Results

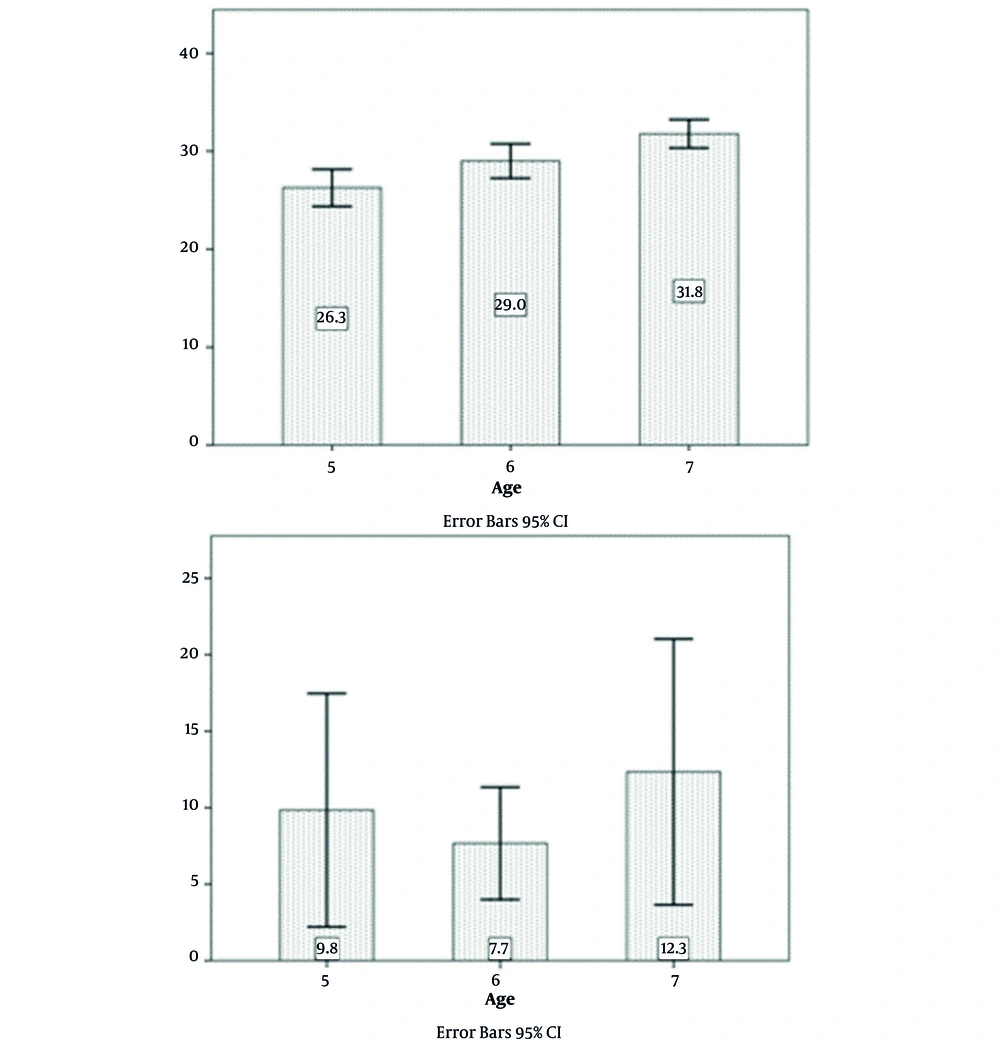

In the present study, 63 children with a mean age of 5.98 ± 0.81 years participated. The youngest and oldest children were 5 and 7 years old, respectively. Also, 21 (33.3%) were girls, and 42 (66.7%) were boys. In this study, children were divided into 2 groups. The first group (n = 18) included children with high-functioning autism (case group) and the second group (n = 45) included typically developed children (control group). There was no significant difference between the ages of the 2 groups (P = 0.92). In the control group, the scores of ToM was increased with age, but in the group of children with autism, there was no relationship between age and scores of ToM (Figure 1).

The results of the independent sample t test showed a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of the mean total score of the ToM test, levels 1 and 2 of mental development score (P < 0.001). Since level 3 of the mental developmental part of the ToM test was not completed by all children in the case group, it was impossible to calculate a statistical test to compare the mean of the 2 groups. Table 1 compares the total scores and subscales of the ToM in the case and control groups.

| Categories | Mean ± SD | Minimum - Maximum | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Bound | Lower Bound | ||||

| Total score of ToM test | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 9.94 ± 6.58 | 3 - 28 | 13.21 | 6.67 | |

| Typical | 28.96 ± 3.78 | 19 - 37 | 30.09 | 27.82 | |

| Level 1 | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 8.78 ± 4.15 | 3 - 17 | 10.84 | 6.71 | |

| Typical | 18.22 ± 1.35 | 15 - 20 | 18.63 | 17.82 | |

| Level 2 | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 1.17 ± 2.96 | 0 - 11 | 2.64 | 0 | |

| Typical | 8.80 ± 2.53 | 1 - 13 | 9.56 | 8.04 | |

| Level 3 | Not measurable | ||||

| ASD | - | - | - | - | |

Comparing the Mean Levels of the Theory of Mind in Typical Children and Children with High-Functioning Autism

The results of the independent sample t tests demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in conventional, symbolic, and combined PEPA. In addition, the typically developed children had higher score on PEPA than children with autism (Table 2).

| Categories | Mean ± SD | Minimum - Maximum | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Bound | Lower Bound | ||||

| PEPA (conventional) | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 46.75 ± 14.29 | 23.8 - 70.8 | 53.85 | 39.47 | |

| Typical | 89.42 ± 8.58 | 56.5 - 98.7 | 91.99 | 86.84 | |

| PEPA (symbolic) | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 35.74 ± 14.77 | 0 - 58.8 | 43.08 | 28.39 | |

| Typical | 86.69 ± 11.49 | 50.5 - 100 | 90.14 | 83.23 | |

| PEPA (combined) | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 43.45 ± 10.53 | 21.9 - 62.7 | 48.68 | 38.22 | |

| Typical | 87.96 ± 9.04 | 53 - 99 | 90.67 | 85.24 | |

| NOS (conventional) | 0.45 | ||||

| ASD | 0.28 ± 0.58 | 0 - 2 | 0.56 | 0 | |

| Typical | 0.62 ± 1.17 | 0 - 5 | 0.97 | 0.27 | |

| NOS (symbolic) | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 2.61 ± 2.15 | 0 - 7 | 3.68 | 1.54 | |

| Typical | 16.47 ± 8.12 | 0 - 33 | 18.90 | 14.03 | |

| NOS (combined) | < 0.001 | ||||

| ASD | 2.89 ± 2.52 | 0 - 9 | 4.14 | 1.64 | |

| Typical | 17.18 ± 8.27 | 4 - 35 | 19.66 | 14.69 | |

Comparing the Percentage of Elaborate Pretend Actions in the Child Initiated Pretend Play Assessment in Typical Children and Children with High-Functioning Autism

The Mann-Whitney and independent sample t test results showed a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of the mean scores of the symbolic NOS and combined NOS. Compared with ASD children, typically developed children had higher scores in symbolic and combined NOS. However, the results of the Mann-Whitney test did not show a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of the mean scores of NOS in conventional play (P = 0.45).

The Mann-Whitney and independent sample t tests showed no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups regarding the mean scores of the conventional, symbolic, and combined NIA (P < 0.05). In other words, children with autism scored similarly to their typically developed peers in conventional, symbolic, and combined NIA.

According to Table 3, there was a positive and significant relationship between ToM and combined PEPA, as well as between ToM and conventional PEPA. However, there was no positive and significant relationship between ToM and PEPA in symbolic play.

| Typical Children (N = 45) | Conventional PEPA | Symbolic PEPA | Combined PEPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total score of ToM | |||

| Correlation | 0.301 a | 0.307 a | 0.347 a |

| Significance level | 0.044 | 0.040 | 0.020 |

| Level 1 | |||

| Correlation | 0.351 a | 0.388 b | 0.427 b |

| Significance level | 0.018 | 0.008 | 0.003 |

| Level 2 | |||

| Correlation | 0.260 | 0.232 | 0.275 |

| Significance level | 0.084 | 0.124 | 0.068 |

| Level 3 | |||

| Correlation | 0.028 | 0.067 | 0.062 |

| Significance level | 0.856 | 0.660 | 0.686 |

| Children with ASD | |||

| Total score of ToM | |||

| Correlation | 0.514 a | 0.365 | 0.649 a |

| Significance level | 0.029 | 0.137 | 0.004 |

| Level 1 | |||

| Correlation | 0.451 | 0.334 | 0.626 b |

| Significance level | 0.061 | 0.175 | 0.005 |

| Level 2 | |||

| Correlation | 0.511 a | 0.342 | 0.564 a |

| Significance level | 0.030 | 0.164 | 0.015 |

| Level 3 | |||

| Correlation | - | - | - |

| Significance level | - | - | - |

The Pearson Correlation Test Between the Theory of Mind and Percentage of Elaborate Pretend Actions in Typical Children with Autism Aged 5 - 7 Years

The Spearman correlation coefficient showed that ToM had no positive and significant relationship with NIA in both typical and autism children. Also, there was a positive and significant relationship between ToM with combined and symbolic NOS in both groups (P < 0.001; Table 4).

| Typical Children (N = 45) | Conventional NOS | Symbolic NOS | Combined NOS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total score of ToM | |||

| Correlation | -0.057 | 0.455 a | 0.425 a |

| Significance level | 0.712 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| Level 1 | |||

| Correlation | 0.097 | 0.440 a | 0.443 a |

| Significance level | 0.524 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| Level 2 | |||

| Correlation | -0.103 | 0.371 b | 0.338 b |

| Significance level | 0.502 | 0.012 | 0.023 |

| Level 3 | |||

| Correlation | -0.080 | 0.201 | 0.170 |

| Significance level | 0.601 | 0.185 | 0.265 |

| Children with ASD | |||

| Total score of ToM | |||

| Correlation | 0.362 | 0.674 a | 0.657 a |

| Significance level | 0.139 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Level 1 | |||

| Correlation | 0.348 | 0.676 a | 0.656 a |

| Significance level | 0.157 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| Level 2 | |||

| Correlation | 0.318 | 0.549 b | 0.540 b |

| Significance level | 0.199 | 0.018 | 0.021 |

| Level 3 | |||

| Correlation | - | - | - |

| Significance level | - | - | - |

The Spearman Correlation Test Between the Theory of Mind and Number of Object Substitutions in Typical Children with Autism Aged 5 - 7 Years

5. Discussion

This study aimed to compare the levels of ToM with the quality of pretend play, including NOS, PEPA, and NIA, in 5 to 7-year-old children with autism and their typically developed peers. The results showed that the ToM test scores were higher in typically developed children than in ASD children. Previous studies have also found consistent results when comparing ASD children with typical children regarding ToM (6, 10, 22-24). In this study, the total score of the first level of ToM was 9.94, which is very low compared to the maximum score of 20. According to ToM test scores, Chan et al. stated that children with high-functioning autism had prerequisites for the early ToM skills, including the perception of desires and emotions, but were not suitable for their age (3). Our results indicated that in children with autism, no growth trend was observed in ToM with age, whereas the mean scores of ToM in typical children was increased with age. According to Kabha and Berger, the stages of ToM varied at different ages (11). Nevertheless, Mansuri et al. also stated that compared with typical children, ASD children had a significant defect in ToM that was not affected by age, and it did not necessarily improve with age (7).

Based on the findings, typical children scored better than ASD children on PEPA and NOS scores. These results are in line with previous studies (13, 24). There was no significant difference between ASD and typical children regarding NIA scores. The average NIA in 2 play sets in typical children was 2.02 and in children with autism was 3.06. Lower NIA scores indicate higher levels of play. Although low NIA scores in typical children can be due to their play ideas, children with autism imitated the examiner’s actions because they did not pay enough attention. Libby et al also stated that problems of children with autism for participating in pretend play and not paying attention to the play led to problems in imitating the actions of pretend play (25). According to Strid et al., imitation in verbal and non-verbal children with autism is impaired (26), which is in line with the findings of the current research. In this study, it was also observed that PEPA and NOS were weaker in ASD children than in typical children, and serious playing defects were seen in these 2 areas.

According to the findings, there was a positive and significant relationship between ToM and PEPA in typical and ASD children. However, this significant relationship was not observed in the conventional imaginary subscales. In previous studies, ToM and play have been related, and even ToM has been called a predictor of playing quality (3, 15). Merino found a negative relationship between pretend play and ToM (27). However, that study was performed on 4-year-old children, which is not comparable to the current study population. Also, the child’s perception of himself/herself and others in the world of mind is highly associated with subsets of actions, gestures, and conversations in the play (8). Nevertheless, these results suggest that the more complex the child's pretend play and plays behaviors, the higher the ToM.

The results also showed no significant relationship between ToM and NIA in either group. Lin et al. also claimed that ToM did not predict the amount of imitation in a child’s play among children with ASD (15). However, our findings indicated a significant relationship between total NOS scores and ToM in both groups, but this relationship was not significant in the conventional imaginary set for typical and ASD children. Lillard and Kavanaugh associated symbols with ToM in 4 to 5-year-old children (28). Lin et al. stated that object substitution was not related to children’s pretend play (15). When a child begins to play, if he/she pretends to be someone else, it can be a pretense to predict ToM (29). Therefore, it can be said that a child with better ToM can place objects in his/her pretend play to a greater extent. It can also be predicted that a child, who places more objects in his/her pretend play, gains a higher score in ToM. Therefore, when a child puts himself/herself in the place of another person in his/her mental state and situations, it shows the good development of his/her ToM ability (30).

Finally, there was no relationship between ToM and NOS in conventional imaginary play. This is because the structure of this part of the play is such that the placement of objects is done to a minimal extent. In contrast, the symbolic play is used to a large extent in the placement of objects because the tools of this play are unstructured objects. However, we can generally admit that there is a positive relationship between pretend play and ToM. The results supported our hypothesis.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings showed that the levels of ToM were much lower in ASD children than in typically developed peers, and the development of ToM in ASD children did not follow the age growth pattern. In contrast, the growth of ToM in typical children followed the growth pattern, and by the age of 8, typical children were more likely to be at the second level of ToM. In addition, the mean scores of pretend play in typical children were higher than ASD children. Therefore, it can be concluded that play skills and ToM are related, and to improve one, one can rely on other interventions. To improve social functioning, play interventions can be considered by clinicians in children with ASDs. We also suggest more studies in clinical trial designs to make sure whether play interventions can improve ToM or not.