1. Background

Acute hepatitis is a term used to specify a wide variety of situations characterized by acute inflammation of the hepatic parenchyma or damage to hepatocytes resulting in increased liver function indices. Several infectious (acute viral hepatitis) and non-infectious diseases (drug-induced hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, cholestasis hepatitis, metastatic disease, etc.) can cause acute hepatitis in children (1). If they are ruled out through laboratory investigations, the term hepatitis of unknown origin is used.

On 5 April 2022, 10 cases of severe acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children younger than 10 years were reported from the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland (2, 3). Rapidly, the numbers increased worldwide, and several cases were reported from different countries. Until 8 July 2022, 1010 probable cases of severe acute hepatitis of unknown origin were reported from five World Health Organization (WHO) regions, which complete the WHO case definition, including 22 deaths (4-10). As of 23 April 2022, approximately 10% of cases required liver transplantation (5). Simultaneously with the global spread of this disease, three children with severe acute hepatitis of unknown origin in a children's medical center in Iran were reported on 25 June 2022 (11).

Considering the unknown nature of this disease and the alarming trend of increasing cases worldwide (4-9), health workers must know the general approach to these patients. To achieve this goal, the Department of Pediatrics, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, has prepared a guideline for dealing with these patients.

2. Arguments

2.1. Case Definition

Confirmed: Currently, WHO and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) do not present definitive definitions.

Probable cases: Probable cases must include all the criteria: Age below 16 years, severe acute hepatitis with aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine transaminase (ALT) above 500 since 1 October 2021, and negative tests for hepatitis E, D, C, B, and A.

Epidemiologically linked cases: Epi-linked cases are defined as patients with acute hepatitis from the beginning of October 2021 at any age who have been in contact with probable cases (6, 8, 12, 13).

2.2. Clinical Presentation and Disease Severity

Before the onset of the main symptoms of hepatitis, most patients mention nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. About a quarter of patients display fever or respiratory symptoms. Then, the main symptoms of hepatitis include jaundice, yellowish color of the skin and eyes, dark-colored urine, pale stool, weakness, anorexia, abdominal pain, and lethargy. Skin rash and the involvement of joints or other organs due to the unknown course of the disease and its causes may occur (11-16). Criteria of disease severity include total bilirubin > 15, prothrombin time (PT) > 20 or international normalized ratio (INR) > 2 resistant to 0.2 mg/kg vitamin k administration, hypoglycemia, and encephalopathy (convulsions, confusion, lethargy, change of sleep-wake rhythm, hallucinations, delirium, lack of awareness of time and place, behavioral and mood changes) (6, 8, 11, 14-16). It is possible that the high level of transaminases (> 1000) also indicates the severity of the disease. Also, PT > 20 sec, INR > 2 not treated by vitamin K regardless of the presence of clinical hepatic encephalopathy or PT > 15, INR > 1.5 indicates the progress of the disease towards fulminant hepatic failure. These cases should be notified to the children's liver transplant centers, and if possible, the patient should be monitored in the intensive care unit (ICU) (6, 8-16).

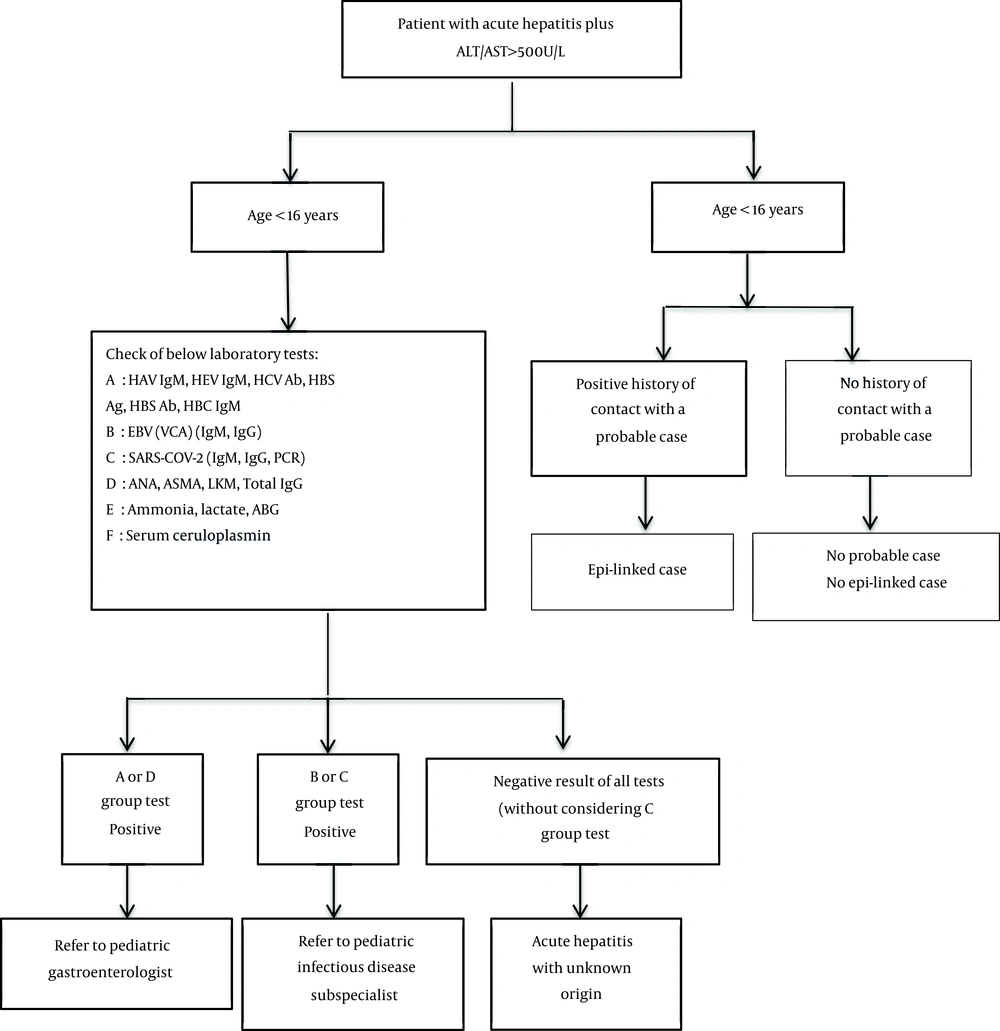

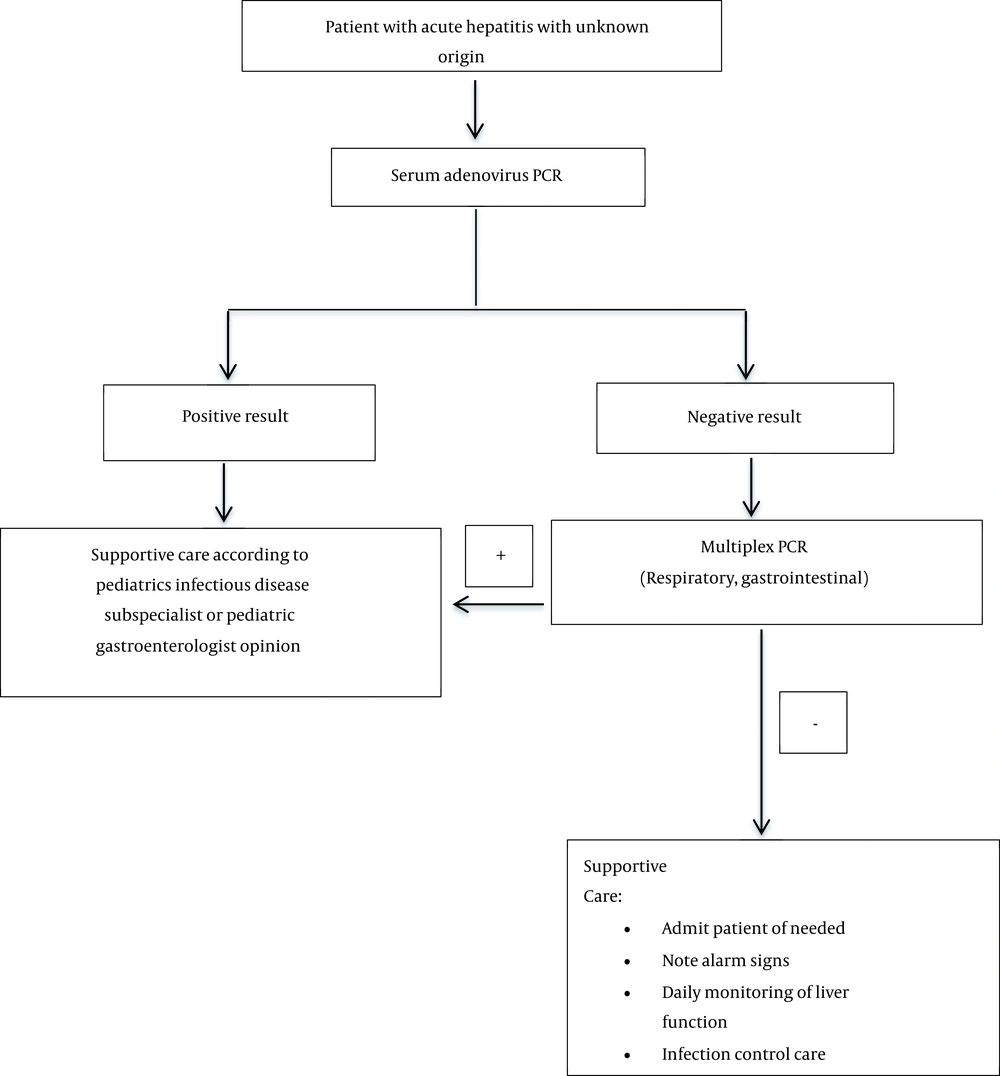

2.3. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Measures/Initial Intervention (Algorithm 1, 2)

It is recommended that general practitioners and pediatricians pay attention to differential diagnosis in patients under 16 years of age, especially under 10, with nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain with or without fever and respiratory symptoms in addition to usual treatments and consider drowsiness, jaundice, dark urine, pale stools, bruises or frequent bleeding on the body surface, severe lethargy and encephalopathy symptoms in follow-up visits. It is recommended that children under six years of age with symptoms of hepatitis be considered for the below points (Table 1) in history taking and physical examination (6, 8-15).

| Points | |

|---|---|

| History taking | Recent travel in the past month |

| Contact with patients with respiratory or digestive infections or hepatitis | |

| Use of chemical drugs, especially acetaminophen, antibiotics, anticonvulsants, and chemotherapy drugs, herbal and homemade ingredients | |

| Consumption of wild mushrooms | |

| Contact with poisons, dyes, and chemicals | |

| COVID-19 vaccination history | |

| Family history of liver diseases | |

| Evidence of metabolic liver diseases (consanguineous parents, other children suffering from liver diseases) | |

| Evidence of autoimmune diseases in the family | |

| History of national routine vaccination | |

| Obtaining a detailed medical history regarding consumption of chemical and household drugs, new or suspicious food, and contact with poisons | |

| Obtaining a detailed medical history regarding COVID-19 or other infections in the last month | |

| Physical examination | Vital signs and blood pressure measurement |

| Jaundice | |

| Bruising | |

| Signs of encephalopathy | |

| Signs of chronic liver disease including enlarged spleen or isolated liver left lobe enlargement, clubbing, and spider angioma (the presence of these findings is against the diagnosis of acute hepatitis with unknown origin) | |

| Signs of cardiac and respiratory involvement | |

| Fever |

The necessary tests for patients suspected of acute hepatitis of unknown origin in children at different referral levels are as follows (Table 2) (6-15).

| First Level (General Practitioner and Family Physician) | Second Level (Children's Outpatient Clinics and General Hospitals) | Third Level (Children's Specialist and Subspecialist Hospitals) | Fourth Level (Children's Subspecialist Hospitals) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBC, CRP, ESR, AST, ALT, ALP, GGT, bilirubin, BUN, Cr, Na, K, PT, INR, PTT, albumin, total protein, BG | HAV IgM, HEV IgM, HBS Ag, HBS Ab, HBC Ab, HCV Ab, Epstein–Barr virus VCA Ab IgM & IgG, CMV (IgM & IgG), SARS-CoV-2 (IgM & IgG), SARS-CoV-2 PCR; at the discretion of the pediatric gastroenterologist: ANA, ASMA, LKM Ab, total IgG, VBG, ceruloplasmin, ammonia, lactate | Blood, respiratory, or feces adenovirus PCR should be done if the second-level tests are negative (regardless of the SARS-CoV-2 test result) | In the case of adenovirus PCR negativity, depending on the type of symptoms (respiratory or digestive), multiplex PCR for respiratory or gastrointestinal test should be sent to the national reference laboratory |

Abbreviations: CBC, complete blood count; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; BG, blood glucose. HAV IgM, hepatitis A virus IgM antibody; HEV IgM, hepatitis E virus IgM antibody; HBS Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBS Ab, hepatitis B surface antigen antibody; HBC Ab, hepatitis B core IgM antibody; HCV Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; VCA Ab, viral-capsid antigen antibody; CMV, cytomegalovirus, PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ANA, antinuclear antibody; ASMA, smooth muscle antibody; LKM Ab, liver/kidney microsome type 1 antibodies; VBG, venous blood gas.

2.4. Outpatient Management

In cases that do not need hospital admission, alarm signs should be explained to the patient and his/her parents. A summary of outpatient management recommendations is seen in Table 3 (6, 8-15).

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Outpatient management | Note warning signs (sleepiness, convulsions, delirium, and other symptoms of encephalopathy, body bruising, bleeding, severe lethargy, worsening of jaundice, frequent vomiting, and food intolerance, and decreased urine volume). |

| Daily visits for clinical signs and symptoms | |

| Checking PTT, INR, PT, CBC, GGT, ALP, ALT, and AST at regular intervals for deciding on hospitalization indication based on the physician's opinion | |

| Emphasis on nutrition with plenty of fluids, fresh fruits and vegetables, and enough calories | |

| Emphasis on avoiding arbitrary use of chemical and household medicines | |

| No close contact with the patient's respiratory secretions and the content of his vomit and feces | |

| Frequent hand washing of the patient and others with soap and water | |

| Adhering to general infection control measures due to the unknown mode of disease transmission |

Abbreviations: CBC, complete blood count; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine transaminase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, gamma glutamyl transferase; PT, prothrombin time; INR, international normalized ratio; PTT, partial thromboplastin time.

2.5. Hospitalization and Inpatient Management

If the liver enzymes are high (ALT/AST > 500 L/U) and total bilirubin > 2 - 3 (direct > 1) with at least one of the below criteria, the patient should be hospitalized: Having an underlying disease (immune deficiency, severe chronic infections, chronic lung, heart, kidney, liver, nervous and metabolic disease), PT > 15 or INR > 1.5, symptoms of encephalopathy (seizures, confusion, drowsiness, changes in the rhythm of sleep and wakefulness, hallucinations, delusions, lack of awareness of time and place, behavioral and mood changes), hypoglycemia, frequent vomiting, and transaminase > 1000 L/U (6, 8-15).

2.6. For the Patients Who Need Hospital Admission, 11 Categories Should Be Noted in Management

2.6.1. Initial Interventions: Including the Following

A. Check vital signs and BS glucometer regularly and perform a neurological examination.

B. Check biochemistry, complete blood count (CBC), liver function test (LFT), ABG (arterial blood gas), ammonia and lactate, blood, urine, and endotracheal secretion culture.

C. Etiology investigation tests according to Table 2.

D. Chest X-ray (CXR) and abdominal ultrasound.

E. Brain CT scan in case of evidence of brain herniation or brain hemorrhage (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.2. Transfer to the ICU

The patient with the following criteria should be transferred to the ICU: Hepatic encephalopathy, cardiovascular instability, multiple organ dysfunction, and hypoglycemia (blood sugar < 55 dL/mg) (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.3. Fluid and Electrolytes Management

Insertion of a central vein catheter is recommended with an arterial catheter, if necessary. After initial resuscitation, total intravenous fluids should be

restricted to around 90% of maintenance fluids to avoid overhydration, followed by dextrose 10% with an amount of 90% maintenance with half saline and 15 meq/L potassium. Maintain blood glucose between 90 - 120 mg/dL. Hypoglycemia resistant to treatment can indicate metabolic disease or adrenal insufficiency requires hydrocortisone. Blood sodium should be maintained at 145-150 meq/L. Blood phosphorus levels should be kept above 3 (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.4. Infection Control

Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered. Tachycardia without cause, gastrointestinal or pulmonary bleeding, elevated urea and creatinine, and change in the level of consciousness can indicate an infectious process. Sepsis work-up, including blood culture, is necessary for all patients (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.5. Hepatic Encephalopathy Treatment

The head should be 30 degrees higher than the rest of the body, and the environment should be calm. Head and body protection with protective pads is recommended. Minimal endotracheal suction should be done. Protein intake should restrict to up to 1 g/kg/d. Lactulose 0.5 - 1 mL/kg (maximum 30 cc per dose) is recommended to the extent that the patient has 2 - 4 soft stools daily. Eliminating risk factors (infection, shock, hypotension, gastrointestinal bleeding, kidney failure, electrolyte disorders such as hypokalemia, and sedative drugs, especially benzodiazepines) is necessary. Tracheal intubation in case of stage 3 encephalopathy, aggressive behavior, and decreased respiratory function should be done (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.6. Brian's Edema Treatment

Abnormality of pupillary reflex, deep tendon reflex (DTR) intensification, Babinski positivity, and hypertensive attack can indicate the onset of edema, and the following treatment should be performed for cerebral edema: Maintaining adequate perfusion, temporary hyperventilation, hypothermia, limitation of liquids administration (75% to 91% maintenance), hypertonic saline 3 - 30% administration (blood sodium should be kept at 145 - 155 meq/L), control of sepsis and convulsions (levetiracetam is preferred and sodium valproate is prohibited), mannitol administration (0.5 - 1 g/kg if serum osmolality < 320 with normal urine output).

Optic nerve sheath ultrasound can be used to check cerebral edema (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.7. Coagulopathy Treatment

Vitamin K administration 0.2 - 0.3 mg/kg, fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets administration in case of active bleeding or procedure, and active 7 factor can be used in case of volume restriction and the need for immediately correcting coagulation disorders before procedures (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.8. Maintaining Renal Function

Maintain urine output above 0.5 cc/kg/h. keep systolic blood pressure above 80 - 90 mmHg according to age. Pay attention to glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in the dosage of drugs. Do not use nephrotoxic contrast agents or drugs; treatment of hypovolemia, and, if necessary, use inotrope drugs, especially norepinephrine (6, 8, 11-14).

2.6.9. Maintaining Cardiovascular Function

The inotrope of choice is norepinephrine. In case of persistent hypotension, adrenal insufficiency should be considered (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.10. Liver Transplantation

In case of a progressive course of liver dysfunction (PT > 20 or INR > 2, 15 < PT or 1.5 < INR with encephalopathy, hepatic encephalopathy, total bilirubin > 15), it is recommended to make arrangements for liver transplant (6, 8, 11-15).

2.6.11. Sedative Use

2.7. Prevention

Preventive measures include avoiding close contact with patients' respiratory droplets and contents of vomit, feces, urine, and blood, frequent hand washing with soap and water, and keeping children away from kindergartens and schools for at least one week after the onset of jaundice (6, 8, 11-15).

2.8. Discharge

If the patient has the following conditions, he/she can be discharged from the hospital:

(1) Persistence of vital signs for at least 48 hours

(2) No electrolyte disorder

(3) Having oral tolerance

(4) Decreasing course of liver tests, especially INR and bilirubin, in the last three days

(5) Bilirubin < 15 mg/dL and INR < 1.5

(6) No hypoglycemia (BS < 55 mg/dL) in the last 48 hours

(7) Absence of cytopenia (6, 8, 11-15)

2.8.1. Recommendations After Discharge

(1) It is recommended that the patient refer immediately in case of daytime sleepiness, convulsions, delirium, sleep-wake rhythm disturbance, frequent vomiting and severe lethargy, severe abdominal pain, bruising, and spontaneous bleeding.

(2) A follow-up visit should be done in the coming days with AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT), CBC, PT, INR, and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) checks and comparing results with previous results, especially for bilirubin and PT/INR.

(3) The patient should be taught the principles of infection control.

(4) The patient should have a diet containing enough liquids, fruits, and vegetables and plenty of calories.

(5) Regular outpatient visits of patients should be done weekly until the liver tests are completely normal.

(6) Considering the possibility of aplastic anemia in viral hepatitis and the involvement of other organs, it is recommended to check CBC-Diff during follow-up visits (6, 8, 11-15).

3. Conclusions

Considering that this disease is spreading daily worldwide (9, 15, 16), the necessary training should be given to the health system employees to diagnose and manage these patients. A step-by-step approach helps pediatricians properly detect and treat these patients (6, 8, 14, 16). Figure 1 shows the way of step-by-step diagnostic investigations in pediatric acute hepatitis. If the diagnosis of hepatitis of unknown origin is determined based on the laboratory results, Figure 2 can be used to continue the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of the patient. The etiology of this disease is still unclear (6, 8, 11, 12, 16, 17), but studies have shown that adenovirus infection (18), autoimmune condition (19-21), and infection or vaccination of COVID-19 (20, 22, 23) may play a role in its initiation.