1. Background

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is one of the most prevalent chronic diseases with childhood onset (1). According to recent epidemiological studies, about 11 to 22 million people worldwide suffer from T1DM, and 90% of diabetic children have T1DM. In recent years, the incidence, prevalence, and severe complications of T1DM have increased significantly (2). Besides, T1DM is an autoimmune disorder characterized by destroying pancreatic beta cells, and patients require long-term insulin therapy to survive, which has multiple limitations (3, 4). For example, insulin therapy can increase glucagon, leading to metabolic syndrome and obesity, which can cause cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and other complications (5). Therefore, several studies have been carried out to find insulin adjunct treatments.

Anti-diabetic oral agents such as incretin mimetics, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, etc., can be used as an insulin adjunct therapy. Still, their side effects are significant and cost a lot (6). Therefore, we should seek insulin adjunct therapy with fewer side effects and costs, and herbal medicines are one of the candidates (7). Pandey et al. reported that about 800 herbs could improve glycemic parameters, and stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.) is one of them (8).

Urtica dioica L. is a perennial flowering plant commonly called stinging nettle, and its application has a deep root in traditional medicine (9). It is a member of the Urticaceae family and includes a variety of biochemicals, including formic acid, acetylcholine, and histamine, as well as beneficial substances such as flavonoids, saponins, phytosterols, tannins, proteins, and amino acids (10). Its derivatives include dry extract, infusion (herbal tea), decoction, crude dried powder, or fresh juice (11). According to previous studies, nettle has many potential therapeutic effects on different diseases, such as allergies (12), arthritis rheumatoid (13), anemia (14), burns (15), internal bleeding (16), kidney stones (17), prostatic hyperplasia (18), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) (19).

The positive effects of nettle on T2DM have been proven to a large extent. Nettle may have diverse mechanisms for affecting glycemic control. The following mechanisms were noted in a molecular and biochemical study by Altamimi et al. (20). Nettle may inhibit alfa-glucosidase enzyme, disaccharidase, and transmission of glucose through glucose transporter 2 (GLUT-2) and decrease glucose transport to caco-2 cells. Boscaro et al. (21) also mentioned increased insulin secretion and sensitivity in addition to inhibiting alfa-amylase activity after nettle use. They also noticed that quercetin is the main component for glycemic control properties, which can be found in the aqueous phase of the extract.

A meta-analysis study based on eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that measured nettle's effects on T2DM demonstrated that nettle might be effective in controlling these patients' fasting blood sugar (FBS) (19). Nettle has anti-inflammatory (22) and antioxidant (23) effects. On the other hand, it can increase glucose uptake by adipose tissue and skeletal muscle (24). These are some of the proposed mechanisms of nettle's impact on diabetes and its complications. Similar to T2DM, inflammation, oxidative stress, and reduced glucose uptake are seen in T1DM (25, 26).

To the best of our knowledge, several RCTs have been conducted on the nettle effects on T2DM patients. Still, no RCT has been conducted on the effects of nettle on T1DM patients.

2. Objectives

The current study aimed to investigate the effects of nettle supplementation on the glycemic parameters of patients with T1DM.

3. Methods

This study is a single-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial with a parallel design. This study enrolled T1DM patients aged 12 - 18 years treated with insulin having inadequate blood sugar control (HbA1c more than 6.5 mg/dL) referred to 17th Shahrivar Hospital, Rasht, Iran, from April to October 2020, with BUN < 20 mg/dL and SCr < 1.5 mg/dL. Patients were excluded if they had a history of previous allergy to nettle food products, had a change of more than 0.3 units in SCr during the study, used medications such as lithium, warfarin, and blood pressure-lowering drugs due to drug interactions, and were unwilling to participate.

For calculating the sample size, we considered the statistical power of 90%, error level of 0.05, d of 1.41, and standard deviation of 0.62 in the intervention group and 1.9 in the control group. The sample size obtained for each group, including a 10% drop rate, was equivalent to a minimum of 23.44, which was rounded up to 24.

The block randomization method with the size of four was used on the following website (Sealedenvelope) to provide a randomization sequence. The numbered sealed and opaque envelopes were used sequentially to hide the random allocation.

Fifty patients were randomly assigned to the intervention and control groups. Patients in the intervention group received 5 mL of nettle syrup twice daily. According to the manufacturer's information, the syrup contained the active ingredient quercetin, with a minimum concentration of 0.04 mg/mL of chlorogenic acid. Along with the nettle syrup, these patients also received insulin. On the other hand, patients in the control group received insulin monotherapy for a duration of 12 weeks. The administered insulin dose in each group was 0.4 - 0.5 units per weight, consisting of one-third subcutaneous glargine once a day and two-thirds subcutaneous as part three times a day. The insulin dose in both groups increased or decreased according to blood sugar during the study. All patients were trained regarding the number of carbohydrate units received and the frequency of testing blood sugar at home. In case of blood sugar drop to less than 70 mg/dL, glucagon ampoules were injected.

Nettle extract was purchased from Zardband® Company, Tehran, Iran, with certified botanical origin in the form of syrup. Due to a lack of data regarding weight-based nettle dose, we omitted younger children for safety issues and dosed the nettle based on the manufacturer's recommendation.

The primary outcome was the changes in FBS, and the secondary outcomes were changes in HbA1c, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and SCr. Data including the following parameters were gathered: Age, sex, weight, underlying disease, use of other medications, rapid-acting and long-acting insulin dose, total insulin dose, FBS, HbA1c, BUN, and SCr. They were checked at the beginning of the study in both groups of patients. After four and eight weeks from the start of the study, FBS and kidney function parameters (BUN and SCr) were rechecked in both groups. At the end of the study period (after 12 weeks), FBS, HbA1c, received insulin dose, and renal function parameters were rechecked.

During the study period, patients were checked for side effects. In case of severe side effects or the patient's intolerance or disinclination, the patient was excluded from the study. Considering the difference in eating habits of the child and family, the frequency of consumption, the child's inclinations, and combining meals, a diet that consisted of 55% carbohydrates, 30% fat (10% saturated and 20% unsaturated), and 15% protein was indicated with the help of a nutritionist. Regarding the potential effect of physical activity on glucose control, the pediatric endocrinologist recommended moderate physical activity three times a week, for at least half an hour each time for both groups.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences (number: IR.GUMS.REC.1401.113 date: 2022-06-01), and the study protocol was registered (IRCT20220516054879N2). A written informed consent letter was obtained from all patients, parents, or guardians in this study.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

Frequency and percentage were used to describe qualitative data and mean and standard deviation were used for quantitative data. For this purpose, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the normality. If the relevant assumptions were established for quantitative variables, independent t-test, paired t-test, and repeated measures tests, and if the assumptions were not established, the Mann-Whitney test, Wilcoxon test, and Friedman test were used. The chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used to check the qualitative variables. The generalized estimating equations test was used to adjust the effects of confounding variables if the relevant assumptions were established. If the assumptions were not established, suitable transformations were used on the data to normalize or establish homogeneity of variance. The software used was IBM SPSS version 26. The significance level was considered below 0.05.

4. Results

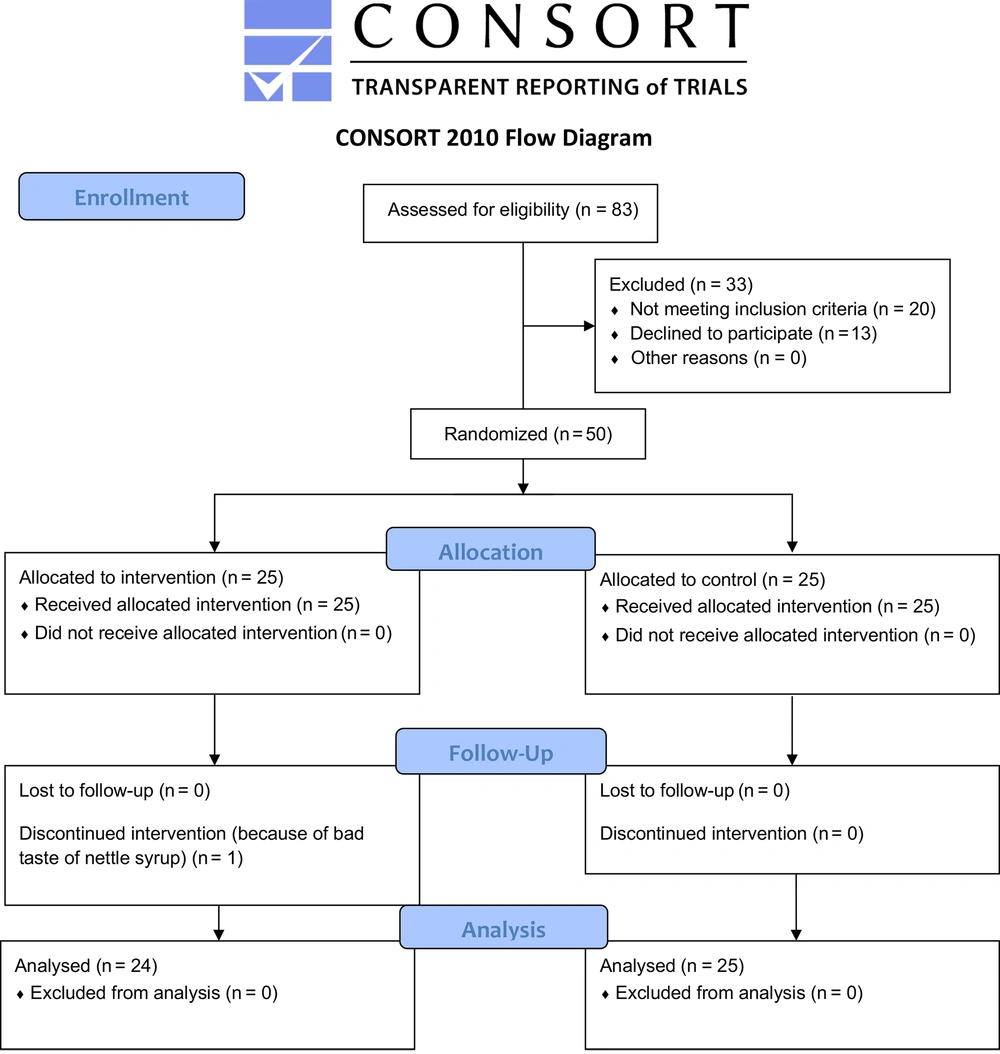

From April 2020 to October 2020, a total of 83 patients were evaluated for eligibility, and finally, 50 patients were randomized at a 1:1 ratio to either the insulin and nettle (n = 25) or insulin monotherapy (n = 25) groups. After study completion, 24 patients in the insulin and nettle group and 25 in the insulin monotherapy group were analyzed (Figure 1).

Table 1 shows the patients' baseline characteristics in the two groups. Patients' mean age, sex, and weight did not significantly differ between the two groups.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise indicated

b Independent samples t-test.

c Pearson chi-square test.

Seventeen patients in the control group (68%) and nineteen in the intervention group (79.1%) had no underlying disease. Eighteen patients in the control group (72%) and twenty in the intervention group (83.3%) did not take any other medications. Comparing the frequency of comorbidities (P = 0.530) and the use of other medications (P = 0.564) in the control and intervention groups using Fisher's exact test showed no significant difference between the two groups.

There was no significant difference in FBS, HbA1c, mean dose of rapid-acting and long-acting insulin, and mean total insulin dose in the intervention and control groups at the beginning of the study. As shown in Table 2, changes in FBS, HbA1c, mean dose of rapid-acting and long-acting insulin, and mean total insulin dose were significant in both groups over time. Besides, the patients in the intervention group experienced a lower increase in mean total insulin dose compared to the control group over time (P = 0.002).

| Variables | Baseline | 4 Weeks | 8 Weeks | 12 Weeks | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBS | |||||

| Intervention | 215.32 ± 37.118 | 178.16 ± 31.474 | 158.38 ± 33.988 | 138.04 ± 20.544 | < 0.001 |

| Control | 218.64 ± 43.998 | 180.00 ± 37.859 | 159.00 ± 24.656 | 134.00 ± 16.862 | < 0.001 |

| P-value | 0.873 | 0.933 | 0.357 | ||

| HbA1c | |||||

| Intervention | 8.43 ± 0.649 | 7.74 ± 0.704 | < 0.001 | ||

| Control | 8.20 ± 0.629 | 7.59 ± 0.624 | < 0.001 | ||

| P-value | 0.332 | ||||

| Dose of rapid-acting insulin | |||||

| Intervention | 17.40 ± 5.115 | 24.50 ± 7.071 | < 0.001 | ||

| Control | 15.80 ± 4.916 | 24.68 ± 6.524 | < 0.001 | ||

| P-value | 0.101 | ||||

| Dose of long-acting insulin | |||||

| Intervention | 8.80 ± 2.769 | 14.83 ± 4.420 | 0.007 | ||

| Control | 8.08 ± 2.812 | 15.92 ± 4.760 | 0.002 | ||

| P-value | 0.10 | ||||

| Total insulin dose | |||||

| Intervention | 26.24 ± 7.790 | 37.96 ± 9.724 | < 0.001 | ||

| Control | 23.88 ± 7.645 | 40.60 ± 10.161 | < 0.001 | ||

| P-value | 0.002 |

Abbreviation: FBS, fasting blood sugar.

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

The mean number of hypoglycemic episodes was not significantly different between the intervention and control groups (P = 0.556), so the patients in the intervention group experienced an average of 0.04 ± 0.20 episodes, and the control group experienced 0.08 ± 0.28 episodes.

Despite the bad odor and taste of nettle syrup, all patients except one tolerated it well, and none reported any significant complications. The trend of BUN and SCr changes was not significant over time (P = 0.532 and P = 0.785, respectively).

5. Discussion

This study evaluated the antihyperglycemic effects of Urtica dioica L. in combination with insulin on the blood glucose level in T1DM pediatric patients. The results indicated no significant difference in glycemic control between the two groups at the end of the study, but mean total insulin doses were significantly lower in the intervention group. Considering the lack of adequate evidence about the antihyperglycemic effects of Urtica dioica L. in T1DM, the authors compared the current results with previous semi-similar animal and human studies in T1DM and T2DM patients.

Amiri Behzadi et al. (27), who evaluated 50 women with T2DM for eight weeks, noted a significant reduction in FBS. Furthermore, Ghalavand et al. (28), in 40 males with T2DM, declared a significant FBS decrease after eight weeks by 10 g/day of nettle extract. Besides, in a case report by Hailemeskel and Fullas (29), a man with T2DM was reported who achieved glycemic control by using nettle despite stopping anti-diabetic medication.

Moreover, Kianbakht et al. (30) administered 500 mg/TDS nettle for three months to patients with T2DM and concluded that this extract significantly decreased blood sugar, postprandial blood sugar, and HbA1c but did not affect SCr and AST.

Ziaei et al., in a systematic review, evaluated five RCTs on nettle supplementation success rate in T2DM and suggested that it may be effective in controlling FBS, HbA1c, and insulin resistance in T2DM patients (19). These results are inconsistent with ours regarding no significant differences in FBS and HbA1c between insulin monotherapy and nettle concomitant use. This may result from assessing different types of diabetes or the effect of diverse inclusion criteria.

Although most studies recommend further clinical trials to determine the efficacy of Urtica dioica L., these studies have shown a significant decrease in blood glucose levels and complications of diabetes through the use of Urtica dioica L. This may be due to its effects on both pancreatic and extra-pancreatic pathways. Additionally, Urtica dioica L. exhibits several pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, hypoglycemic, and anti-oxidative activities (31, 32).

Riazi et al. assessed a study on 24 rats and eight patients between 7 and 24.6 years and concluded that nettle, a glucose-lowering agent for treating T1DM, could reduce blood sugar without increasing insulin secretion (33).

Mobasseri et al. (34) reported that the decrease in blood glucose levels with nettle is attributed to glycogenesis, the blocking of potassium channels in pancreatic beta cells, and its involvement in glucose absorption from the intestinal wall. Most of these effects are similar to those of insulin. On the other hand, nettle extract can reduce blood glucose levels in diabetic mice due to GLUT-2 gene expression in mice's liver (10, 34, 35). Mobasseri et al. (36) mentioned inconsistent results that the alcoholic extract of nettle could not enhance glucose utilization directly or by increasing the insulin sensitivity in muscle cells (29, 36).

These results are consistent with Tarighat Esfanjani et al. (37) and Tabrizi et al. (38), who believed the hydroalcoholic extract of nettle reduced FBS and HbA1c after eight weeks of intervention in patients with T2DM (37, 38). Because of these reasons, the effectiveness of insulin improves, and the units of short-acting and long-acting insulin decrease. These may explain our study findings that mean total insulin dose was lower in the intervention group after 12 weeks.

Regarding the side effects of nettle, Goorani et al. (39) tried different doses of nettle in a study on 60 rats with STZ-induced DM and found that it could decrease blood sugar and prevent kidney hypertrophy. Ahangarpour et al. (40) mentioned increased AST and ALT after nettle use. In the study by Kianbakht et al. in 2013, after eight weeks of using nettle extract, it was observed that SCr was not different between the intervention and control groups. Nettle does not show toxic effects on the kidneys (30). However, according to our study, the slight but not significant increase in SCr after nettle consumption shows that a study with larger sample size and longer follow-up duration should be performed to investigate these side effects thoroughly.

This study had the following limitations. The small sample size and single-center design of the study reduced statistical power and generalizability. We did not measure endogenous insulin levels or c-peptide. Regarding the shortage of evidence on the optimal weight-based dose of nettle, we administered a single fixed dose. Therefore, performing larger multicenter trials with longer follow-up, measuring insulin levels, assessing optimal dosing, monitoring additional outcomes, and studying diabetes complications is recommended.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study showed that both groups had decreased levels of FBS and HbA1c. However, we found lower total insulin dose in the intervention group that may emphasize this positive effect through insulin-sensitizing mechanism or increasing insulin secretion.

Based on the shortage of evidence on the optimal dose of nettle in patients with T1DM, we recommended larger multicenter studies with large sample sizes over long periods.