1. Background

Cardiomyopathy (CM) is a rare clinical entity in children, and its annual frequency is 1.13 per 100 000. The causes of childhood CMs vary, and the cause cannot be identified in more than 60% of patients. Myocarditis, familial isolated CM, neuromuscular diseases, inherited metabolic disorders (IMDs), and genetic syndromes are the most common causes of pediatric CM (1-3). Inherited metabolic disorders are often multisystem disorders that show an acute or progressive clinical course and can be classified as intoxication-type disorders, energy metabolism disorders, and disorders involving complex molecules. It has been reported that IMDs constitute approximately 5% of all pediatric CM cases and 15% of known CM causes (2). Cardiovascular involvement accompanies 15% - 60% of IMDs, including CM, heart valve disorders, rhythm-conduction disorders, and congenital cardiac structural disorders (3-5). Accumulation of substrate in cardiac myocytes, impaired energy metabolism, and/or production of toxic intermediary metabolites are responsible for the pathogenesis of cardiac findings in IMDs (2). In pediatric cardiomyopathies, the prognosis can be improved by determining the cause and specific rapid treatment and management. However, it is not always possible to detect nonspecific symptoms and multifactorial etiological causes of these diseases (6, 7).

2. Objectives

We examined the clinical, echocardiographic, and electrocardiographic findings and prognoses of patients diagnosed with CM associated with an IMD in our clinic.

3. Methods

We retrospectively evaluated the clinical findings of patients who were diagnosed with CM associated with an IMD at a university hospital between January 2010 and December 2020. Patients with CM were evaluated by routine biochemical tests and metabolic investigations, including enzyme analysis. Patients with glycogen storage disease (GSD) were diagnosed by single-gene sequencing or targeted gene panels for GSD. Patients with lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) were diagnosed by lysosomal enzyme analysis and single-gene sequencing. Patients with fatty acid oxidation disorders and amino acid and organic acid metabolism disorders were diagnosed by quantitative acylcarnitine and amino acid analysis, urinary organic acid analysis, and single gene sequencing. If these investigations did not reveal any specific diagnosis, whole exome analysis (WES) was performed. Patients with mitochondrial disorders were diagnosed by WES.

Inclusion criteria were as follow: (1) Patients aged 0 - 18 years who were investigated for the etiology of CM and diagnosed as having IMD by biochemical and genetic analyses later; and (2) patients who had a specific IMD and developed CM on follow-up.

Exclusion criteria included patients with a genetically or biochemically unconfirmed diagnosis of IMD.

3.1. Clinical Data

Initial admission symptoms, time of onset of symptoms, sex, family history, age of diagnosis, pathogenic variants, type of CM, presence of symptoms associated with CM, electrocardiography and imaging findings, echocardiographic results of the patients at the time of diagnosis of CM and final echocardiographic findings, follow-up periods, whether or not they received specific treatment for IMD, time of initiation of cardiac support treatment, data on mortality status, post-treatment cardiac evaluation, and follow-up were obtained from patient records. Patients were classified according to the definition of the Pediatric Cardiomyopathies Registry (PCMR) (1) as having hypertrophic CM (HCM), dilated CM (DCM), restrictive CM, left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC), arrhythmogenic CM, or a mixed phenotype.

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the children in the study.

3.2. Echocardiography

Left ventricular diameters and wall thickness were measured from the parasternal short-axis view at the level of the mitral valve leaflet tips. From these measurements, LV volume, ejection fraction, and mass were calculated (8, 9). Systolic and diastolic measurements were performed at end-systole and end-diastole of the same cardiac cycle. The M mode was used for the calculation of the shortening fraction (9). All Z scores were calculated using the normative database at the Children’s Hospital of Boston (8).

3.3. DNA Extraction and Variant Analysis

Peripheral blood samples (2 mL) were collected from patients who were referred to Cukurova University AGENTEM (Adana Genetic Diagnosis and Treatment Center) and the Medical Genetics Department of the Medical Faculty. DNA samples were isolated using an automated DNA isolation system (QIAcube, Qiagen, Germany) using the Qiagen DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Concentrations were measured using a fluorometer (Qubit 3.0). All samples were proceeded to fragmentation, and sample-specific molecular barcodes were added by adapter ligation. Barcoded samples were targeted and enriched for genes (all exons and exon-intron junctions) with a custom-designed kit containing gene-specific primers. Amplicons were labeled with a universal adapter prior to next-generation sequencing, and sample libraries were generated. Finally, next-generation sequencing was performed via the Illumina Miseq platform with a minimum coverage of 100X. Quality control and bioinformatics analyses were performed using QCI-Analyze and QCI-Interpret.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of the distribution for continuous variables was confirmed by Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogrov-Smirnov tests. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, whereas continuous variables were summarized as the mean and SD and as the median and minimum-maximum, where appropriate. For the comparison of continuous variables between two groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. For non-normally distributed data, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare more than 2 groups. For comparison of paired variables measured at diagnosis and the last visit, the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test was used. Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the factors affecting survival. Kaplan-Meier curves with a log-rank test were performed for survival analysis. The level of statistical significance for all tests was 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Clinical Characteristics

A total of 102 patients, including 58 (57%) males and 44 (43%) females, were diagnosed with IMD-related CM at a mean age of 26.2 ± 28.2 months. Families with consanguineous parents (n = 86) constituted 84.3% of the study population, while 27 patients had a previously affected sibling (26.5%). Twelve (11.8%) patients had a history of sibling death associated with IMDs. Eleven (10.8%) patients with CM were diagnosed with CM in the pediatric cardiology outpatient clinic and referred to the pediatric nutrition and metabolism clinic for metabolic evaluation. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 44 (43.1) |

| Male | 58 (56.9) |

| Positive consanguinity | 86 (84.3) |

| Previously affected sibling | 27 (26.5) |

| History of sibling death due to IMDs | 12 (11.8) |

| Siblings who died from unknown causes | 42 (41.2) |

| Age at presentation (mon); median (min - max) | 3.5 (0.03 - 130) |

| Age at IMD diagnosis (mon); median (min - max) | 7 (0.40 - 157) |

| Time between first symptoms and IMD diagnosis (mon); median (min - max) | 2.5 (0.2 - 140) |

| Age at CM diagnosis | 26.2 ± 28.2 |

| Follow-up durations (mon)(min-max) | 60.9 ± 54.6 (1 - 288) |

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients

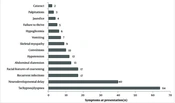

At the time of diagnosis of CM, tachypnea or, dyspnea or both were detected in 64 patients (62.7%; Figure 1).

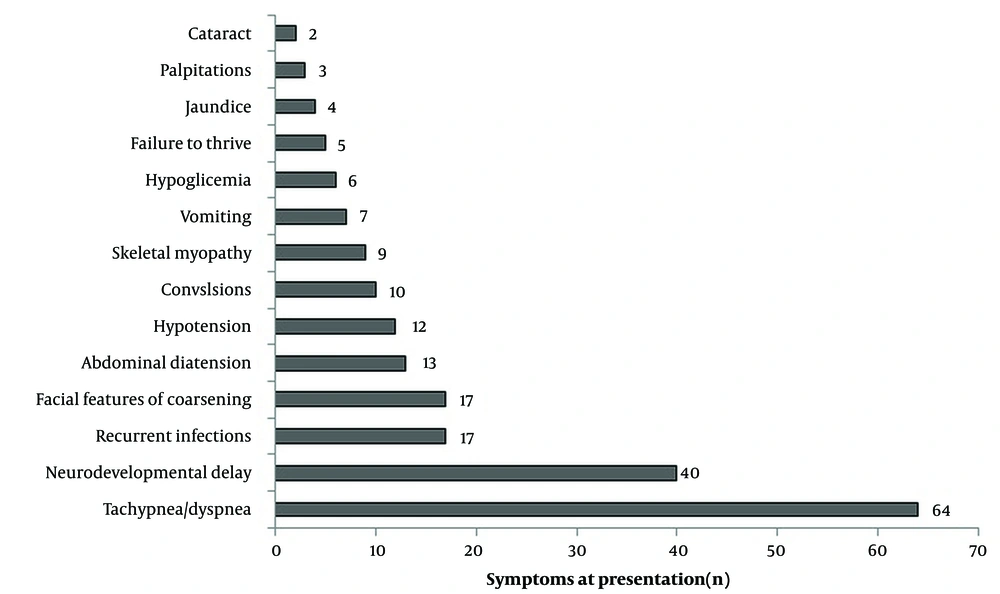

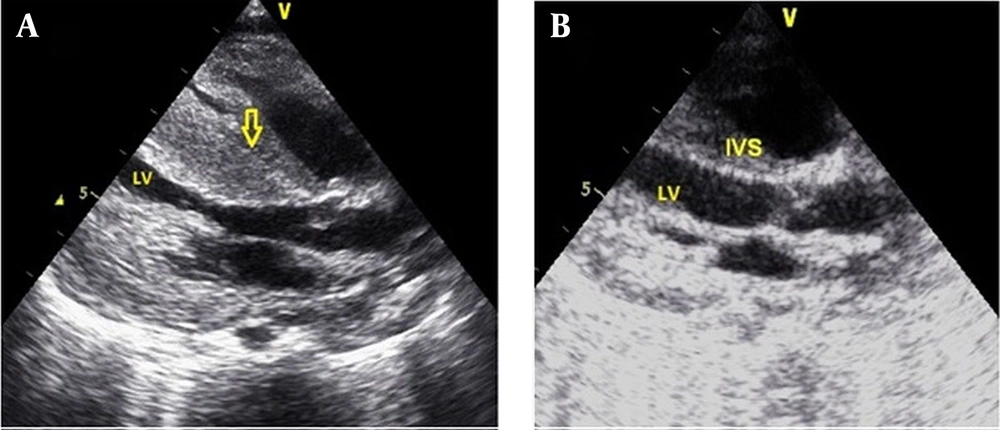

In 84 patients (82.4%), cardiomegaly was detected on telecardiography. Overall, 86 patients (84.3%) were diagnosed with HCM, 12 (11.7%) with DCM, and 4 (3.9%) with mixed type (DCM/LVNC). The most common group of IMDs causing CM was GSD (60 patients, 58.8%), followed by LSDs (17 patients, 16.7%), mitochondrial disorders (11 patients, 10.8%), fatty acid oxidation disorders (11 patients, 10.8%), and amino acid and organic acid metabolism disorders (3 patients, 2.9%). Glycogen storage disease was the most common etiology in HCM (Figure 2), while fatty acid oxidation disorders were the most common etiology in DCM (Figure 3).

The IMD groups, specific IMD diagnoses, and associated CM types of the patients are shown in Table 2. Left ventricular dysfunction (defined as a shortening fraction < 28%) was documented in 30 (29.7%) patients.

| IMDs Groups and Specific IMD Diagnoses | No. (%) | Type of CM (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Pompe disease | ||

| Infantile pompe | 47 (46) | HCM (46), DCM-LVNC (1) |

| GSD | 13 (12.7) | |

| GSD-III | 12 (11.7) | HCM (11), DCM- LVNC (1) |

| GSD-IB | 1 (0.98) | HCM (1) |

| LSD | 17 (16.7) | |

| MPS-1 | 7 (6.8) | HCM (6), DCM (1) |

| MPS-2 | 5 (4.9) | HCM (5) |

| MPS-6 | 3 (2.9) | HCM (3) |

| Mucolipidosis II | 1 (0.98) | DCM-LVNC (1) |

| Cystinosis | 1 (0.98) | HCM (1) |

| Fatty acid oxidation disorders | 11 (10.8) | |

| Primary carnitine deficiency | 7 (6.8) | DCM (4), HCM (3) |

| CPT II deficiency | 1 (0.98) | HCM (1) |

| VLCAD | 1 (0.98) | HCM (1) |

| MCAD | 2 (1.9) | DCM (2) |

| Mitochondrial disorders | 11 (10.8) | |

| Complex 1 deficiency | 4 (3.9) | DCM (1), HCM (3) |

| Sengers syndrome | 2 (1.9) | HCM (2) |

| Barth syndrome | 1 (0.98) | DCM (1) |

| Leigh syndrome a | 1 (0.98) | DCM (1) |

| COXPD38 | 1 (0.98) | HCM (1) |

| Mitochondrial complex V (ATP synthase) deficiency | 2 (1.9) | HCM (2) |

| Amino acid and organic acid metabolism disorders | 3 (2.9) | |

| Partial biotinidase deficiency | 1 (0.98) | DCM-LVNC (1) |

| 3-MCCD | 1 (0.98) | DCM (1) |

| Methylmalonic acidemia | 1 (0.98) | DCM (1) |

| Total | 102 (100) | - |

Metabolic Disease Groups, Specific Metabolic Disease Diagnoses, and Associated Cardiomyopathy Types of the Patients

4.2. Genetic Testing

While previously defined pathogenic variants were detected in 77 patients, novel pathogenic variants were found in 22 (21.6%) patients. Genetic analyses of 3 patients revealed no pathogenic variants. One patient had glycogen storage type 1, and she was diagnosed via enzyme analysis. Two patients had mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) type 2, and both received a diagnosis via enzyme analysis; multiple sulphatase deficiency had been ruled out. The distribution of pathogenic variants was as follows: 88 patients had homozygous pathogenic variants (86.2%), 6 patients had compound heterozygous pathogenic variants (5.9%), 4 patients had hemizygous pathogenic variants (3.9%), and 1 patient had mitochondrial DNA pathogenic variants (1%; Appendix 1).

4.3. Long-Term Follow-Up

The mean follow-up period of the remaining 95 patients was 60.9 ± 54.6 months, except for 7 patients (5 HCM, 1 DCM, and 1 DCM-LVNC) who were lost to follow-up. During the follow-up period, 24 (23.5%) patients had hemodynamically significant or insignificant arrhythmia detected in 24-h Holter records and/or electrocardiography, and 18 (17.6%) patients had conduction problems (Table 3).

| Variables | No. (%) | IMDs (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac conduction disorders | 14 (13.8) | |

| Right bundle branch block | 13 (12.7) | Pompe (3), LSD (2), GSD III (2), Fatty acid oxidation disorders (4), Mitochondrial disorders (2) |

| 2-degree sinoatrial block | 1 (1) | Pompe (1) |

| WPW type preexcitation | 4 (3.9) | Pompe (4) |

| Arrhythmia | 24 (23.5) | |

| SVT | 8 (7.8) | Pompe (4), LSD (1), GSD3 (3) |

| Ventricular ectopy | 7 (6.9) | Pompe (3), LSD (1), Mitochondrial disorders (2), Fatty acid oxidation disorders (1) |

| Supraventricular ectopy | 5 (4.9) | LSD (1), GSD III (1), Fatty acid oxidation disorders (3) |

| Torsades de pointes | 1 (1) | Pompe |

| SVT + ventricular ectopy | 1 (1) | Pompe |

| WPW syndrome | 1 (1) | Mitochondrial disorders |

| SVT + VT | 1 (1) | Mitochondrial disorder |

Distribution of Rhythm-Conduction Problems Seen During Follow-up in Patients with Cardiomyopathy

All patients with conduction anomalies were asymptomatic. Eight patients with ventricular ectopy and 7 patients with supraventricular ectopy were symptom-free, and no treatment was needed. Three of the patients with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) presented with respiratory distress and 2 with palpitations. Two patients had short-term, multiple SVT attacks detected by Holter electrocardiogram (ECG). Supraventricular tachycardia was followed by VT, and bradycardia developed in 1 patient. This patient was resuscitated, but the patient died. Electrical cardioversion was performed in 2 patients with SVT and 1 patient with Torsades de Pointes. Diuretics (n = 40; 39.2%), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (n = 38; 37.3%), beta-blockers (n = 24; 23.5%), and cardiac glycosides (n = 20; 19.6%) were the most commonly used drugs for cardiac problems. In 22 patients, intravenous positive inotropic treatment was needed during follow-up. All patients were diagnosed with CM, and follow-up echocardiographic data are given in Table 4.

| Variables | (n = 47) | (n = 12) | (n = 17) | (n = 11) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pompe Disease | GSD III | LSD | Fatty acid Oxidation Disorders | Mitochondrial Disorders | |||||||||||

| During Diagnosis | At Last Follow-up | P | During Diagnosis | At Last Follow-up | P | During Diagnosis | At Last Follow-up | P | During Diagnosis | At Last Follow-up | P | During Diagnosis | At Last Follow-up | P | |

| LVSF (%)c | 32.6 ± 9.7 | 37 ± 5.3 | 0.03 | 38.3 ± 5.2 | 35.9 ± 5.1 | 0.18 | 36.5 ± 8.8 | 36.4 ± 7.2 | 0.95 | 28 ± 9.7 | 37 ± 5.9 | 0.01 | 31.3 ± 12 | 31.6 ± 8 | 0.72 |

| LVEDd (mm) | 22.7 ± 5 | 30.5 ± 5.4 | 0.00 | 35.8 ± 7.5 | 38 ± 6.5 | 0.08 | 34.7 ± 5 | 37.7 ± 8 | 0.05 | 34.9 ± 15 | 37.4 ± 11 | 0.21 | 27.4 ± 7.5 | 30 ± 6.3 | 0.14 |

| LVEDd (Z score)d | 0.8 ± 2.6 | 0.4 ± 2.3 | 0.56 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.7 ± 1 | 0.37 | 2.3 ± 2.7 | 1.4 ± 2.8 | 0.19 | 3.3 ± 3.8 | 1.1 ± 2.4 | 0.09 | 4 ± 4.7 | 2.5 ± 2.6 | 0.79 |

| IVSd (Z score)d | 13.2 ± 5.5 | 5 ± 4.5 | 0.00 | 5 ± 3.1 | 3.6 ± 2.6 | 0.38 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 3 | 0.38 | 4.4 ± 2.7 | 2.2 ± 1.8 | 0.05 | 4.1 ± 2.8 | 4.6 ± 3.1 | 0.81 |

| LVPWd(Z score)d | 12 ± 5.5 | 3.7 ± 4.2 | 0.00 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 2.1 | 0.81 | 3 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 2.1 | 0.17 | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 2 ± 1.6 | 0.07 | 4.2 ± 2.4 | 5 ± 3.9 | 0.72 |

| LV mass index (gr/m2) e | 277 ± 127 | 118 ± 86 | 0.00 | 105 ± 30 | 101 ± 38 | 1.00 | 114 ± 27 | 118 ± 57 | 0.90 | 144 ± 65 | 95 ± 34 | 0.05 | 141 ± 56 | 136 ± 73 | 0.44 |

Forty-two patients (42/47) with infantile Pompe disease, all patients with MPS type 1 (n = 7) and type 2 (n = 5), and 2 (2/3) of the MPS type 6 patients received enzyme replacement therapy (ERT; Figure 3). Forty percent of the patients (n = 38) required mechanical ventilation during follow-up who were diagnosed as having Pompe disease (n = 17), mitochondrial diseases (n = 9), lysosomal storage diseases (n = 5), fatty acid oxidation defects (n = 4), organic acidemias (n = 2), and GSD other than Pompe disease (n = 1).

4.4. Mortality

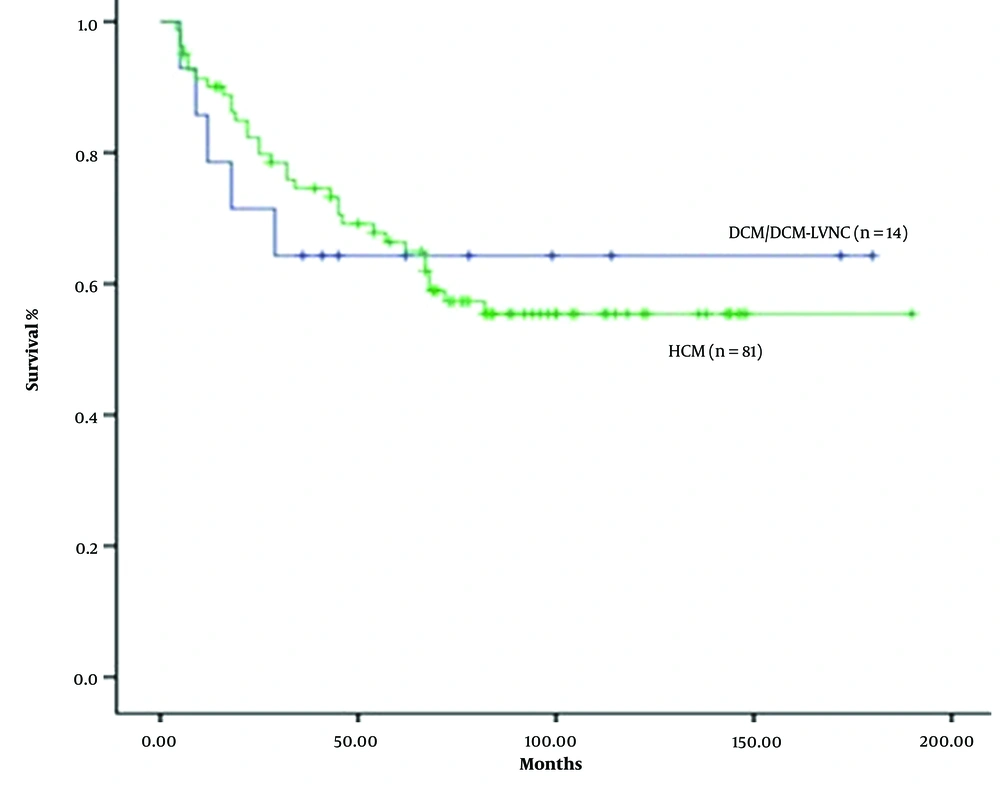

The 12-month survival rate after diagnosis was 85%. DCM/DCM-LVNC patients had the worst 12-month survival rate (64%), and patients with HCM had better survival rates (88%). However, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.16; Figure 4).

Overall, 38 (40%) of 95 patients with regular follow-up died. Of the patients who died, 21 (55,2%) were diagnosed as having Pompe disease, 8 (21%) were in the group of LSDs, 5 (13%) were in the group of mitochondrial disorders, 2 (5%) had fatty acid oxidation disorders, 1 patient (3%) had GSD type III, and 1 patient (3%) had organic acidemia. Patients died due to cardiac and non-cardiac complications. The causes of death were cardiac insufficiency, arrhythmias, sepsis, respiratory insufficiency, and acute metabolic decompensation. Patients with Pompe disease died due to lower respiratory system infections and/or cardiac arrhythmia. Patients with other lysosomal storage diseases and mitochondrial diseases died due to pneumonia and respiratory insufficiency. Patients with fatty acid oxidation disorders were lost due to cardiac insufficiency and arrhythmias. A patient with GSD died due to acute hepatic failure. A patient with organic academia was lost during an acute metabolic decompensation. Thirty-three (87%) of the patients who died had HCM, and 5 (13%) had DCM/DCM-LVNC.

4.5. Impact of Cardiomyopathy Type on Survival

In a multiple regression analysis conducted to investigate the factors affecting the patients’ survival, those with amino acid and organic acid metabolism disorders were excluded from the evaluation because they could not reach enough patients for statistical analysis. The effects of age at CM diagnosis, CM type, IMD type, shortening fraction, ejection fraction, left ventricular posterior wall diameter (Z score), interventricular septum in diastole (Z score), and left ventricular mass index (g/m2) on survival were investigated. Multiple regression analysis showed that CM type, shortening fraction, ejection fraction, left ventricular posterior wall diameter (Z score), interventricular septum in diastole (Z score), left ventricular mass index, and CM diagnosis age were found to be ineffective in survival (P > 0.05). Having LSDs was a negative factor in terms of survival compared to having GSD (P = 0.021; Table 5).

| Variables | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis | 1.017 | 0.996 - 1.038 | 0.115 |

| LVSF | 1.239 | 0.898 - 1.71 | 0.192 |

| LVEF | 0.892 | 0.708 - 1.124 | 0.331 |

| LVPWd (Z score) | 0.982 | 0.814 - 1.184 | 0.849 |

| IVSd (Z score) | 0.995 | 0.835 - 1.185 | 0.953 |

| LV mass index (gr/m2) | 0.997 | 0.988 - 1.007 | 0.602 |

| IMDs | |||

| GSD | 1 | ||

| LSDs | 0.139 | 0.026 - 0.745 | 0.021 |

| Fatty acid oxidation disorders | 1,3 | 0.174 - 9.702 | 0.798 |

| Mitochondrial disorders | 0.481 | 0.085 - 2.707 | 0.406 |

| Type of CM | 0.71 | 0.081 - 6.253 | 0.757 |

Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Affecting Survival in Patients with Cardiomyopathy

5. Discussion

Inborn errors of metabolism are often found to be associated with cardiomyopathies (4, 11). More than 40 IMDs have been reported to cause CM (2). Glycogen metabolism disorders, LSDs, fatty acid oxidation disorders, mitochondrial disorders, and amino acid and organic acid metabolism disorders may lead to cardiomyopathies. A delayed diagnosis may lead to irreversible cardiac complications. Due to the high occurrence of consanguineous marriages in our region, there is a significant prevalence of IMDs. Therefore, our aim was to investigate and evaluate the situation within our patient cohort.

In IMDs, a heterogeneous group of diseases, the age of the first symptom and the age of diagnosis differ. In a study in which a group of IMDs accompanied by CM were evaluated together, the mean age of diagnosis was reported to be 2.6 years (12). In our study, this period was 20.2 ± 31.5 (0.4 - 157) months. Tachypnea-dyspnea, neurodevelopmental delay, convulsions, recurrent attacks of vomiting, hypoglycemia, hypotonia, failure to thrive, coarse facial features, and metabolic acidosis are important indicators of the potential presence of IMDs. In this study, the most frequently reported symptom was tachypnea. While tachypnea was associated with heart failure in some patients, it was associated with metabolic acidosis due to acute metabolic decompensation caused by intoxication-type IMDs in others.

Cardiomyopathies have been reported to be more common in males than in females (2, 12). In our study, we found male dominance (57% vs. 43%). The male predominance in our study may be related to X-linked IMDs, such as MPS type 2 and Barth syndrome. Most IMDs are autosomal recessively inherited, and IMDs should be suspected in the case of a family history of CM with an undetermined cause or child death with an unknown cause. The fact that 26.5% of our patients had a family history of IMDs and 41.2% had a history of child death of unknown cause supports this view. One of the reasons why these rates were high in our study is that consanguineous marriages are still frequent in Turkey. According to the latest data, the frequency of consanguineous marriages in Turkey is 8.4% (13). Although this rate is lower compared to many Middle Eastern countries, it remains significantly higher than the rates observed in developed countries (14, 15). With improvements in diagnostic tools, it has been reported that 26% of HCMs and 16% of DCMs are related to IMDs (16). Glycogen storage disease, mitochondrial disorders, and fatty acid oxidation disorders are reported to be the most common IMDs that cause HCM, while DCM is most commonly caused by mitochondrial disorders and fatty acid oxidation disorders (2, 17). Cox detected HCM in 63.8%, DCM in 21.3%, and other types of cardiomyopathies except restrictive CM in 14.9% of the patients diagnosed with IMDs (2). Almost half of the patients with HCM due to IMDs have GSD (18). The frequency and distribution of IMDs may vary between populations as they are affected by genetic and epigenetic factors. In our study, while HCM constituted a large proportion of our patients, we found GSD II (Pompe disease) to be the most common cause. Cardiomyopathy has not been reported in patients with a partial biotinidase deficiency. We think that this coexistence is coincidental in our case.

Various arrhythmias and conduction problems can be observed due to cardiac involvement in IMDs. A prolonged QTc interval and ventricular tachycardia have been reported in newborns with very long- and medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiencies (19). In many cases, heart rhythm disorder is the major presenting symptom leading to the diagnosis of the underlying inborn error. Similarly, cases of primary systemic carnitine deficiency with a prolonged QTc interval and arrhythmia have been reported (20). Arrhythmias can also appear in later stages of storage disorders secondary to progressive heart dysfunction and do not usually consist of a prominent clinical finding in early childhood with the exemptions of Pompe and Danon diseases (3, 21). The incidence of arrhythmia has been reported to be 18% in Pompe patients receiving ERT, including ventricular and supraventricular ectopy, SVT, and VT (2 patients had corrected QT length) (22). Studies that include the transgenic mouse model of AMP-activated protein kinase γ2 have provided an anatomical explanation for the cause of Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome in glycogen storage CM (23). Byrne et al. reported that SVT developed in 10 patients, WPW syndrome developed in 2 patients, and right bundle branch block developed in 1 patient during the treatment period in 113 patients (treatment-related or unrelated) (24). Similarly, in this study, the most common arrhythmia was SVT, while VT was detected in 2 patients (1 due to corrected QT length). This patient, with a prolonged QTc interval, was a Pompe patient receiving ERT. Four out of 5 patients with WPW-type preexcitation were Pompe patients, and SVT was not observed in any of them.

Cardiomyopathy findings may regress or improve with the appropriate treatment of the underlying IMD (16, 24). Conventional drugs (inotropes, diuretics, and antiarrhythmic drugs) and supportive treatments are used in the management of cardiac complications. A significant number of our patients also needed these medications during the follow-up. The long-term management of cardiac problems depends on the underlying disease. In primary carnitine deficiency, CM is expected to improve with carnitine supplementation (25). In 7 of our cases with primary carnitine deficiency, the findings improved with carnitine supplementation. Enzyme replacement therapy has also been reported to have positive effects on the cardiac findings in some diseases, such as Pompe disease, Fabry disease, MPS type 1, MPS type 2, and MPS type 6 (24, 26). Although ERT leads to improved CM findings (geometry and contraction of the cardiac muscle) in LSDs, no significant improvement has been reported in valve structures and functions (27, 28). However, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for the improvement of respiratory involvement, which indirectly affects the prognosis of cardiac manifestations. In fact, while the present study found a significant improvement in cardiac findings in Pompe patients with ERT, there was no significant improvement in the echocardiographic findings of CM in patients with other LSDs. However, the relatively small number of patients in this group prevents us from reaching a definitive judgment.

Although the prognosis in IMDs is largely affected by underlying diseases, mortality is generally higher in cases with CM. Colan et al. examined the results of a group of patients with HCM and reported that HCM due to IMDs showed the worst prognosis (29). van der Beek reported that CM increased mortality in infantile Pompe disease (30). Although in this study, the highest number of patients who died was in the Pompe disease group, the highest ratio of deceased patients was in the LSD and mitochondrial disorder groups. The type of CM had no effect on mortality.

The low number of patients in patient groups other than GSD is one of the most important limitations of our study. The patients with LSDs receiving ERT prevent us from making an inference about the cardiac effects of enzyme therapy in this group of patients, as there was no control group without treatment.

Most of the IMDs leading to CM can be diagnosed through extended newborn screening programs. However, in Turkey, only phenylketonuria and biotinidase deficiency are included in the newborn screening program. As a result, cardiac manifestations can be identified in IMDs either at first admission as a presenting sign or during follow-up as a complication. Cardiac involvement causes a significant increase in morbidity and mortality rates. There is a continuous effort to implement regional selective screening and extended newborn screening. Until then, periodic screening should be performed for cardiac involvement in the follow-up of children with IMDs. An evaluation should be made in terms of underlying IMDs in unexplained CM and rhythm disorders. Future strategies should aim to decrease consanguineous marriages to reduce the prevalence of autosomal recessive disorders, including IMDs. Also, genetic counseling is crucial to avoid the recurrence of these diseases in the same family. Even though genetic diagnosis for future pregnancies is not mandatory, families should be encouraged to undergo carrier screening and prenatal and preimplantation diagnoses.