1. Background

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) infection is a major cause of digestive disorders in children (1). Patients with Hp infection may develop indigestion, gastric and duodenal ulcers, etc. (2). Hp infection can damage the gastric mucosa and affect inflammatory factor levels, resulting in gastrointestinal symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and loss of appetite, thus leading to malnutrition and stunted development (3), which may affect the normal growth and nutritional status of children. Hp infection has been reported to significantly participate in the development of dyspepsia, which can cause malnutrition in children (4).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to test and clarify whether Hp infection affects the physical development and nutritional indicators of children with Hp infection before and after eradication treatment.

3. Methods

3.1. General Information

This study included 112 children diagnosed with Hp infection from the outpatient and inpatient departments of our hospital between January 2020 and June 2021. The study group consisted of 63 boys and 49 girls, with an average age of 9.7 ± 2.0 years. Additionally, the control group consisted of 100 healthy children who had undergone a physical examination in the outpatient department of our hospital during the same period. The control group included 44 girls and 56 boys, with a mean age of 9.6 ± 1.9 years. No significant difference was found in age and sex between the two groups (P > 0.05).

3.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

(1) Children who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for Hp infection, which included testing positive for endoscopic pathological staining, rapid urease test, and/or 13C-urea breath test (5)

(2) Children aged 7 - 14 years.

3.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

(1) Children diagnosed with serious organic illnesses

(2) Children diagnosed with acute infectious diseases in the last month

(3) Children who had received Hp eradication treatment

(4) Children who had used vitamin preparations or trace element supplements within half a year

(5) Children with a positive 13C-urea breath test after eradication treatment

(6) Children who failed to complete follow-up due to poor compliance.

3.2. Method

Treatment involved administering omeprazole orally twice a day at a dose of 0.6 - 1.0 mg/kg.d, with a maximum dose of 20 mg per time. Amoxicillin was given orally twice a day at a dose of 50 mg/kg.d, with a maximum dose of 1 g per time. Clarithromycin was administered orally twice a day at a dose of 20 mg/kg.d, with a maximum dose of 0.5 g per time, and colloidal bismuth subcitrate at a dose of 6 - 8 mg/kg.d (twice a day orally) for 2 weeks. The children with Hp infection enrolled in this study underwent a 13C-urea breath test 4 weeks after treatment and were followed up for 1 year. Furthermore, this study recorded the physical development and nutritional indicators of the enrolled children before and 1 year after eradication treatment. Data were obtained from the hospital information and management system. Various patient information, including main clinical features, and laboratory tests, were collected.

3.3. Sampling and Detection

Before and 1 year after treatment, 5 mL of peripheral venous blood was extracted from each child with Hp infection, and 5 ml of peripheral venous blood was drawn from healthy children during their physical examinations.

3.4. Measurement of Physical Development Indicators

The body height and weight of these children were measured in the same environment after defecation and urination in the morning and on an empty stomach.

3.5. Detection of Nutritional Indicators

Baoding Key Laboratory of Clinical Research on Children’s Respiratory and Digestive Diseases assessed nutritional indicators. Haemoglobin (Hb) was measured using a Mindray BC-5300 Auto Hematology Analyzer. Serum ferritin (SF) and serum iron (SI) were detected using a Beckman Coulter-AU5800 biochemical analyzer using test kits provided by Beckman Coulter and Abbott Laboratories, respectively. The level of 25-(OH)D3 was detected by chemiluminescence using an i2000 chemiluminescence instrument (Abbott Laboratories) with the test kit provided by Abbott Laboratories. Additionally, the albumin (ALB) level was tested using the bromocresol green method using the AU5800 biochemical analyzer with the test kit purchased from Beckman Coulter.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

SPSS 25.0 was utilized for conducting data analysis. The measurement data were represented using (

4. Results

4.1. General Data

Overall, 112 children infected with Hp responded to treatment without any loss to follow-up; 23 (20.5%) children were classified into the recurrence group as they showed a positive 13C-urea breath test after 1-year follow-up. The remaining 89 (79.5%) children were included in the non-recurrence group as they showed negative results in the 13C-urea breath test after 1-year follow-up. The recurrence group included 13 boys and 10 girls, whereas the non-recurrence group consisted of 50 boys and 39 girls. The average age was 9.6 ± 2.0 and 9.7 ± 2.0 years in the recurrence and non-recurrence groups, respectively. Table 1 shows that there was no significant difference in sex and age between the recurrence group and non-recurrence groups (P > 0.05).

| Groups | Number of Cases | Sex | Average Age, y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Recurrence group | 23 | 13 (56.5) | 10 (43.5) | 9.6 ± 2.0 |

| Non-recurrence group | 89 | 50 (56.2) | 39 (43.8) | 9.7 ± 2.0 |

| χ2/t value | 0.001 | 0.356 | ||

| P-value | 0.976 | 0.723 | ||

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

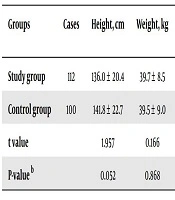

4.2. Comparison of Physical Development and Nutritional Indicators Between the Study and Control Groups Before Eradication Treatment

Table 2 indicates that before eradication treatment, the study group had significantly lower levels of Hb, SI, SF, and 25-(OH)D3 compared to the control group (P < 0.05). However, there were no meaningful differences observed in body height, body weight, and ALB levels between the study and control groups (P > 0.05).

| Groups | Cases | Height, cm | Weight, kg | 25-(OH)D3, ug/L | Serum Iron, μmoL/ L | Serum Ferritin, μg/L | Hemoglobin, g/L | Albumin, g/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | 112 | 136.0 ± 20.4 | 39.7 ± 8.5 | 26.5 ± 5.8 | 12.3 ± 2.3 | 24.0 ± 6.6 | 122.3 ± 6.1 | 46.4 ± 6.5 |

| Control group | 100 | 141.8 ± 22.7 | 39.5 ± 9.0 | 33.0 ± 5.6 | 13.4 ± 2.4 | 28.3 ± 6.5 | 126.8 ± 9.0 | 47.6 ± 6.9 |

| t value | 1.957 | 0.166 | 8.278 | 3.401 | 4.769 | 4.299 | 1.303 | |

| P-value b | 0.052 | 0.868 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.194 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Independent samples t-test.

4.3. Comparison of Nutritional Indicators Between the Study and Control Groups After 1 Year of Eradication Treatment

Table 3 reveals that after 1 year of eradication treatment, there were no significant differences observed in the levels of Hb, SF, SI, 25-(OH)D3, and ALB between the control and study groups (P > 0.05).

| Groups | Cases | 25-(OH)D3, ug/L | Serum Iron, μmoL/L | Serum Ferritin, μg/L | Hemoglobin, g/L | Albumin, g/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | 112 | 32.3 ± 6.2 | 13.1 ± 1.5 | 26.7 ± 6.4 | 125.2 ± 6.7 | 47.5 ± 7.0 |

| Control group | 100 | 33.0 ± 5.6 | 13.4 ± 2.4 | 28.3 ± 6.5 | 126.8 ± 9.0 | 47.6 ± 6.9 |

| t value | 0.858 | 1.100 | 1.803 | 1.477 | 0.104 | |

| P-value b | 0.392 | 0.273 | 0.073 | 0.141 | 0.917 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Independent samples t-test.

4.4. Comparison of Nutritional Indices Between the Recurrence and Non-Recurrence Groups After 1 Year of Eradication Treatment

No significant differences were noted in the levels of Hb, SI, SF, and ALB between the recurrence and non-recurrence groups after 1 year of eradication treatment (P > 0.05). Table 4 demonstrates that the level of 25-(OH)D3 in the recurrence group was lower than that in the non-recurrence group after 1 year of eradication treatment (P < 0.05).

| Groups | Cases | 25-(OH)D3, ug/L | Serum Iron, μmoL/L | Serum Ferritin, μg/L | Hemoglobin, g/L | Albumin, g/L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence group | 23 | 28.8 ± 4.2 | 12.9 ± 1.4 | 25.6 ± 5.7 | 124.3 ± 5.6 | 46.6 ± 8.7 |

| Non-recurrence group | 89 | 33.2 ± 6.3 | 13.1 ± 1.6 | 27.0 ± 6.6 | 125.4 ± 7.0 | 47.7 ± 6.5 |

| t value | 3.121 | 0.680 | 0.934 | 0.717 | 0.675 | |

| P-value b | 0.002 | 0.498 | 0.352 | 0.475 | 0.501 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Independent samples t-test.

5. Discussion

Importantly, Hp infection is strongly linked to the development of chronic digestive system infections, which have an extremely low rate of natural remission (6). Hp infection has emerged as a disease posing a critical threat to the growth and development of children. Hp infection may recur after eradication treatment, with a high recurrence rate observed in children (7, 8). In our study, 20.5% of children with Hp infection retested positive for the 13C-urea breath test 1 year after eradication treatment, indicating a high recurrence of Hp infection in this region.

Individuals with Hp infection may experience symptoms such as anorexia, malabsorption, and dysregulation of neuroendocrine hormones (e.g., leptin and ghrelin), which are independent risk factors for short stature (9-11). After Hp infection, patients may develop iron deficiency due to gastrointestinal bleeding, increased iron absorption by bacteria, and reduced dietary iron absorption (12). Moreover, it can lead to malabsorption of vitamin D and other vitamins, significantly affecting the nutritional status of infected individuals (13-15). Ultimately, this can have a negative impact on the growth and development of children, as well as on Hb, trace elements, SF, and SI levels (13, 16, 17). Previous studies have demonstrated the relationship between iron deficiency and anemia in children (18, 19).

In this study, before eradication treatment, children with Hp infection had lower levels of SF, SI, Hb, and 25-(OH)D3 compared to healthy children. We believe that Hp infection may impact children's health in various ways, leading to appetite loss and poor nutrient absorption, resulting in anemia and vitamin D deficiency. Furthermore, this study evaluated the nutritional indicators of children with Hp infection after 1 year of successful eradication treatment. No significant differences were found in the levels of Hb, SI, SF, 25-(OH)D3, and ALB between infected and healthy children. It can be inferred that after eradication treatment for Hp infection, there is a rapid recovery of the internal environment of Hp-infected children, resulting in improvements in nutritional indicators in vivo. From another perspective, it confirms that Hp infection affects the nutritional indicators of children to some extent.

Low 25-(OH)D3 levels may be associated with the recurrence of Hp infection in children (20). In this study, the 25-(OH)D3 levels of children with Hp infection recurrence 1 year after successful eradication treatment were lower than those of children without relapse. Although there were no significant differences in Hb, SI, SF, and ALB levels, a decrease in 25-(OH)D3 levels may contribute to an increased risk of Hp infection recurrence.

5.1. Conclusions

The current study found no significant differences regarding body height, weight, and ALB levels between Hp-infected children and their healthy counterparts. Our study findings reveal that Hp infection alone may have no significant effect on the growth indicators of children, although Hp infection may cause symptoms of the digestive system and affect the levels of SI, 25-(OH)D3, and other nutritional indicators. This study had several limitations, such as a smaller sample size and failure to exclude and analyze the impact of family socioeconomic factors on the enrolled children.