1. Background

Oral health is one of the most crucial public health priorities around the world (1, 2). It is an integral part of public health that affects various aspects of life, such as swallowing and nutrition, speech, personal appearance, sleep, and social interactions (3, 4). Although oral and dental diseases are preventable, dental caries remains the most common chronic disease among children and adolescents, affecting up to 80% of schoolchildren in some areas (5, 6). As a result, promoting oral health from an early age is essential for maintaining healthy teeth in adulthood. Schools, in collaboration with pediatricians and dentists, can significantly impact by educating children and guiding parents on proper oral hygiene and the prevention of dental problems (7). The World health organization (WHO) recommends that regular oral health examinations using valid and reliable tools should be conducted every five years (8). These evaluations, along with epidemiological information, provide valuable insights into risk factors, quality of life related to oral health, interventions, treatments, medical service usage, and their quality (9).

Measuring oral health involves various methods such as clinical examination, interviews, Self-assessment questionnaires, or a combination of these approaches (10). The WHO has introduced DMFT as one of the accepted clinical indicators to determine the prevalence of caries, and two indicators of gingival bleeding and periodontal pocket depth to check periodontal condition (11). However, conducting clinical studies can be expensive and time-consuming, requiring specialized tools and trained examiners. This has led to an increased use of questionnaires in oral health studies, which can provide reliable information even in large populations and reduce the limitations associated with clinical studies (12-15).

The WHO has introduced the Oral Health Self-assessment Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (WHO-OHSQ). This questionnaire includes 14 questions divided into three areas: Demographic information, oral health, and habits (habits related to health behaviors, nutrition behaviors, and behaviors related to tobacco and alcohol) (11). This questionnaire has been translated and validated in Arabic and Spanish for children and adolescents (16, 17).

Experience during the pandemic has shown that clinical examinations were restricted due to the increased risk of respiratory diseases. Dental offices were identified as high-risk environments for cross-infection among patients, dentists, and health professionals. Consequently, the health sector and patients showed reduced interest in clinical examinations. Most dental offices worldwide limited their activities to emergency services only during the first few months of the COVID-19 pandemic. The patient's willingness to undergo dental examinations or treatments is expected to remain low for some time, even after the pandemic ends or until the fear subsides completely (18-22).

As a result, one of the most effective ways to assess oral health in large populations, remote regions, or even during an epidemic like COVID-19 is by using an oral health Self-assessment questionnaire. This method helps save time and money, which are significant obstacles to conducting these assessments.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to translate and validate the Persian version of the WHO-OHSQ, specifically for children and adolescents, to overcome these barriers and ensure that oral health can be evaluated effectively.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Kerman, Iran, from March to August 2022, under the code of ethics IR.KMU.REC.1400.134. The study included participants between 7 and 18 years old (11). Since the dental system and its importance vary based on age, students were divided into two groups: 7 - 12 years old with mixed dentition and 13 - 18 years old with mostly permanent teeth. The questionnaire questions were examined separately for each group. After preparing the final questionnaire, permission to distribute it in schools was obtained from the Education Department. We gathered a list of schools in Kerman City, ranging from elementary to high school, and then chose 30 of them through simple random sampling.

The school administrators were provided with the questionnaires and were requested to ask the teachers to distribute them online in their class groups. It was emphasized that participation in the study was completely voluntary, the questionnaires were anonymous, and the information would be used solely for data analysis. Before filling out the questionnaire, the respondents were required to inform their parents about the participation and obtain their consent. They were then required to fill out the questionnaires under their parents' supervision. All students between 7 and 18 years old who attended the selected schools were included. Individuals who were absent from class or those who did not agree to participate were excluded.

The sample size for this study was determined based on previous research (23). The comprehensibility of the questionnaire was tested with a group of 20 students, and then 40 students were selected to assess the consistency of the questionnaire. To assess the validity and reliability, the questionnaire was distributed to 30 schools, each with at least 200 students, and finally, 878 individuals completed the questionnaire online.

3.2. Translation and Back Translation

The back translation method was used to translate the questionnaire from Persian to English. First, two dentists proficient in English translated the original English version (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File) into Persian. Then, two bilingual translators with sufficient proficiency in Persian-to-English translation, who had not seen the original manuscript, translated the Persian version back into English. These versions were then evaluated by three dentists. Finally, any discrepancies between the translations were resolved.

3.3. Pilot Questionnaire

The questionnaire was distributed to 20 individuals who were asked to provide feedback on any issues they encountered while filling it out. Any questions that were difficult to understand were revised. After ensuring clarity and fluency, the final version of the questionnaire was prepared. As this questionnaire has been developed and thoroughly reviewed by professionals within the WHO, ensuring its content, we strictly focused on providing an accurate translation without making any modifications or alterations to its content.

3.4. Validity and Reliability of the Questionnaire

To ensure the consistency of the responses, the final version of the questionnaire was filled out by 40 individuals. The same individuals were given the questionnaire again after a week, and reliability was evaluated using the test-retest method and intra-cluster correlation coefficient. Additionally, due to the limitation of clinical evaluation of DMFT during the Coronavirus pandemic, researchers added three questions to check concurrent validity:

(1) Do you currently have a tooth that is in pain, but you have not visited the dentist? A, yes; B, no.

(2) Do you currently have a tooth that has been filled due to decay? A, yes; B, no.

(3) Do you have a tooth with endodontic treatment due to severe decay? A, yes; B, no.

To ensure the questionnaire's internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha was calculated for the total score, individual items, and if the item was deleted. For questions with binary answers, the Kuder-Richardson 20 index was used to check internal consistency.

The questionnaire had two main areas: Oral health and habits (habits related to health behaviors, nutrition behaviors, and behaviors related to tobacco and alcohol). Explanatory factor analysis was employed to evaluate the construct validity by assessing these areas across distinct components.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The information was statistically collected and analyzed using SPSS23 software. The significance level in the study was set at 5%. To measure reliability, the intra-cluster correlation coefficient and Cronbach’s alpha coefficient were calculated. The acceptable range of values for Cronbach’s alpha was 0.6 to 0.95 (24). Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO), Bartlett’s test, and explanatory factor analysis were used to assess construct validity. In explanatory factor analysis, the factor loadings indicate how the items of the questionnaire influence a component. The factor loadings range from -1 to 1, with values of -1 and 1 representing strong negative and positive influences, respectively. A factor loading of 0.35 is regarded as significant (25).

4. Results

After reviewing the three versions of the original language, translation, and back-translation by three dentists, no discrepancies were found among the versions, and the questionnaire was prepared in Persian. Question number twelve, which was related to smoking, was removed due to the non-agreement of the Kerman Education Department. Additionally, even if there was agreement, the percentage of correct answers would be very low due to the taboo nature of the topic. During the pilot phase, conflicts related to the question about location were resolved. This question included three options: Rural, Urban, and Peri-urban. However, due to the lack of familiarity of the participants with the concept of peri-urban, only two options, urban or rural, were used. Finally, we ensured the clarity and fluency of the questionnaire (Appendix 2 in Supplementary File). To ensure the consistency of the questionnaire results, the intra-cluster correlation coefficient was determined for both age groups (under and over 12 years old) for each question. The coefficient range for all questions was between 0.81 and 0.97.

The study involved 878 participants, with an average age of 13.5 ± 2.9. 63.9% of the participants were female, and all of them lived in urban areas. Of the participants, 290 were between 7 and 12 years old, and 588 were between 13 and 18 years old. According to Table 1, over 60% of the participants rated their oral health as good, very good, or excellent. Additionally, individuals over 12 years old rated their oral health condition as good, very good, or excellent in a higher proportion than children under 12 (P = 0.002). Furthermore, more than 80% of participants used fluoride toothpaste to brush their teeth at least once a week. Finally, children under 12 years old experienced more pain and visited the dentist more frequently in the last 12 months.

| Variables | Age Range | P-Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| > 12 | ≤ 12 | ||

| How would you describe the health of your teeth and gums? | 0.002 a | ||

| Very poor | 10 (1.70) | 7 (2.60) | |

| Poor | 42 (7.30) | 25 (9.40) | |

| Average | 135 (23.40) | 67 (25.20) | |

| Good | 148 (25.60) | 94 (35.30) | |

| Very good | 137 (23.70) | 44 (16.50) | |

| Excellent | 105 (18.20) | 29 (10.90) | |

| How often during the past 12 months did you have toothache or feel discomfort due to your teeth? | 0.127 | ||

| Never | 238 (42.40) | 84 (31.50) | |

| Rarely | 186 (33.20) | 91 (34.10) | |

| Occasionally | 116 (20.70) | 78 (29.20) | |

| Often | 21 (3.70) | 14 (5.20) | |

| How often did you go to the dentist during the past 12 months? | 0.001 a | ||

| Once | 113 (20.10) | 56 (21.10) | |

| Twice | 359 (63.90) | 150 (56.40) | |

| Three times | 36 (6.40) | 35 (13.20) | |

| Four times | 13 (2.30) | 15 (5.60) | |

| More than four times | 11 (2.00) | 2 (0.80) | |

| I had no visit to dentist during the past 12 months | 30 (5.30) | 8 (3.00) | |

| I have never received dental care/visited a dentist | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| What was the reason for your last visit to the dentist? | 0.209 | ||

| Pain or trouble with teeth, gums or mouth | 86 (36.10) | 31 (26.70) | |

| Treatment/follow-up treatment | 44 (18.50) | 25 (21.60) | |

| Routine check-up of teeth/treatment | 24 (4.00) | 5 (1.80) | |

| How often do you clean your teeth? | 0.098 | ||

| Never | 49 (8.10) | 23 (8.40) | |

| Several times a month | 45 (7.50) | 19 (6.90) | |

| Once a week | 110 (18.20) | 34 (12.40) | |

| Several times a week | 280 (46.40) | 150 (54.50) | |

| Once a day | 95 (15.80) | 44 (16.00) | |

| Two or more times a day | 20 (3.30) | 4 (1.50) | |

| Do you use toothpaste to clean your teeth? | 0.052 | ||

| No | 5 (96.70) | 19 (98.50) | |

| Yes | 583 (18.40) | 271 (18.90) | |

| Do you use toothpaste contains fluoride? | 0.077 | ||

| No | 96 (16.32) | 67 (23.10) | |

| Yes | 492 (83.67) | 223 (76.89) | |

a Statistically significant at 5% level.

Table 2 displays the coefficients related to Cronbach's alpha of the questionnaire. Cronbach's alpha for all questions that follow the Likert scale was calculated as 0.656 for individuals under 12 years old and 0.643 for individuals over 12 years old. In addition, Cronbach's alpha was more than 0.6 if any item was removed. For question 8, which had six parts with binary answers of yes or no, the Kuder-Richardson 20 index was used to calculate internal consistency, and its value was 0.39 for individuals under 12 years old and 0.376 for those over the age of 12.

| Variables | Cronbach's Alpha if Item Deleted (≤ 12) | Cronbach's Alpha if Item Deleted (> 12) |

|---|---|---|

| How would you describe the health of your teeth and gums? | 0.683 | 0.667 |

| How often during the past 12 months did you have toothache or feel discomfort due to your teeth? | 0.669 | 0.64 |

| How often did you go to the dentist during the past 12 months? | 0.649 | 0.653 |

| How often do you clean your teeth? | 0.667 | 0.658 |

| I am not satisfied with the appearance of my teeth | 0.674 | 0.654 |

| I often avoid smiling and laughing because of my teeth | 0.66 | 0.643 |

| Other children make fun of my teeth | 0.66 | 0.642 |

| Toothache or discomfort caused by my teeth forced me to miss classes at school or miss school for whole days | 0.663 | 0.645 |

| I have difficulty biting hard foods | 0.662 | 0.648 |

| I have difficulty in chewing | 0.656 | 0.643 |

| How often do you eat or drink any of the following foods, even in small quantities? Fresh fruit | 0.656 | 0.645 |

| Biscuits, cakes, cream cakes, sweet pies, buns etc. | 0.657 | 0.644 |

| Lemonade, Coca Cola or other soft drinks | 0.658 | 0.643 |

| Jam/honey | 0.652 | 0.64 |

| Chewing gum containing sugar | 0.634 | 0.612 |

| Sweets/candy | 0.601 | 0.628 |

| Milk with sugar | 0.618 | 0.612 |

| Tea with sugar | 0.62 | 0.689 |

| Coffee with sugar | 0.604 | 0.602 |

Tables 3 and 4 show the correlation between the questions of the questionnaire and three additional questions about the presence of toothache without dental visits, the presence of a filled tooth, and the presence of a tooth with endodontic treatment. The results indicate that, in both age groups, the questions about describing the health of teeth and gums, the feeling of toothache in the last 12 months, difficulty in biting and chewing, and satisfaction with the appearance of teeth all have a statistically significant relationship (P < 0.05) with the three additional questions. Conversely, the questions on milk consumption with sugar, tea with sugar, and coffee with sugar did not show a significant relationship with any of the three additional questions.

| Variables | Question Onea | Question Two b | Question Three c |

|---|---|---|---|

| How would you describe the health of your teeth and gums? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.327 d | -0.118 d | -0.125 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| How often during the past 12 months did you have toothache or feel discomfort due to your teeth? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.601 d | 0.124 d | 0.215 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| How often did you go to the dentist during the past 12 months? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.236 d | 0.226 d | 0.119 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| How often do you clean your teeth? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.013 d | 0.013 | 0.015 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.006 | 0.447 | 0.466 |

| Do you use toothpaste to clean your teeth? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.013 | -0.214 | -0.105 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.449 | 0.616 | 0.185 |

| Do you use toothpaste that contains fluoride? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.254 | 0.132 | 0.123 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.109 | 0.346 | 0.502 |

| I am not satisfied with the appearance of my teeth | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.112 d | 0.124 d | 0.114 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| I often avoid smiling and laughing because of my teeth | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.123 d | 0.017 | 0.049 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.164 | 0.042 |

| Other children make fun of my teeth | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.112 | -0.105 | 0.101 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.427 | 0.388 | 0.269 |

| Toothache or discomfort caused by my teeth forced me to miss classes at school or miss school for whole days | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.104 d | 0.043 | 0.039 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.402 | 0.104 | 0.150 |

| I have difficulty biting hard foods | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.232 d | 0.106 d | 0.150 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| I have difficulty in chewing | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.276 d | 0.083 d | 0.117 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.001 |

| How often do you eat or drink any of the following foods, even in small quantities? Fresh fruit | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.201 d | 0.044 | 0.017 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.192 | 0.611 |

| Biscuits, cakes, cream cakes, sweet pies, buns etc | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.226 | -0.137 | -0.140 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.411 | 0.213 | 0.137 |

| Lemonade, Coca Cola or other soft drinks | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.204 d | -0.121 | -0.140 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.539 | 0.234 |

| Jam/honey | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -.273 d | -0.112 | -0.220 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.130 | 0.533 | 0.149 |

| Chewing gum containing sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.041 | -0.024 | 0.007 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.122 | 0.277 | 0.135 |

| Sweets/candy | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.101 | -0.131 d | -0.115 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.773 | 0.036 | 0.021 |

| Milk with sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.132 | -0.120 | -0.143 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.149 | 0.162 | 0.102 |

| Tea with sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.105 | -0.018 | -0.176 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.814 | 0.151 | 0.025 |

| Coffee with sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.114 | -0.012 | -0.170 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.680 | 0.345 | 0.040 |

a Do you currently have a tooth that is in pain, but you have not visited the dentist?

b Do you currently have a tooth that has been filled due to decay?

c Do you have a tooth with endodontic treatment due to severe decay?

d Statistically significant at 5% level.

| Variables | Question One a | Question Two b | Question Three c |

|---|---|---|---|

| How would you describe the health of your teeth and gums? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.427 d | -0.218 d | -0.135 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| How often during the past 12 months did you have toothache or feel discomfort due to your teeth? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.401 d | 0.324 d | 0.115 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| How often did you go to the dentist during the past 12 months? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.336 d | 0.126 d | 0.319 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.026 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| How often do you clean your teeth? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.113 d | 0.313 | 0.115 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.006 | 0.447 | 0.466 |

| Do you use toothpaste to clean your teeth? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.113 | -0.314 | -0.515 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.490 | 0.322 | 0.435 |

| Do you use toothpaste that contains fluoride? | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.121 | 0.231 | 0.452 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.109 | 0.346 | 0.502 |

| I am not satisfied with the appearance of my teeth | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.223 d | 0.327 d | 0.236 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| I often avoid smiling and laughing because of my teeth | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.231 d | 0.117 | 0.238 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.164 | 0.042 |

| Other children make fun of my teeth | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.214 | -0.215 | 0.311 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.427 | 0.388 | 0.269 |

| Toothache or discomfort caused by my teeth forced me to miss classes at school or miss school for whole days | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.213 d | 0.213 | 0.123 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.704 | 0.940 |

| I have difficulty biting hard foods | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.324 d | 0.213 d | 0.411 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.000 |

| I have difficulty in chewing | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.231 d | 0.234 d | 0.132 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.001 |

| How often do you eat or drink any of the following foods, even in small quantities? Fresh fruit | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.123 d | 0.292 | 0.149 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.192 | 0.611 |

| Biscuits, cakes, cream cakes, sweet pies, buns etc. | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.232 | -0.122 | -0.231 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.411 | 0.213 | 0.137 |

| Lemonade, Coca Cola or other soft drinks | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.451 d | -0.231 | -0.231 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.539 | 0.234 |

| Jam/honey | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.231 d | -0.231 | -0.543 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.130 | 0.533 | 0.149 |

| Chewing gum containing sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.212 | -0.355 | 0.346 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.122 | 0.277 | 0.135 |

| Sweets/candy | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.213 | -0. 231 d | -0.451 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.773 | 0.036 | 0.021 |

| Milk with sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.237 | -0.349 | -0.218 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.149 | 0.162 | 0.102 |

| Tea with sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.231 | -0.231 | -0.231 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.814 | 0.151 | 0.025 |

| Coffee with sugar | |||

| Correlation Coefficient | -0.123 | -0.121 | -0.231 d |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.680 | 0.345 | 0.040 |

a Do you currently have a tooth that is in pain, but you have not visited the dentist?

b Do you currently have a tooth that has been filled due to decay?

c Do you have a tooth with endodontic treatment due to severe decay?

d Statistically significant at 5% level.

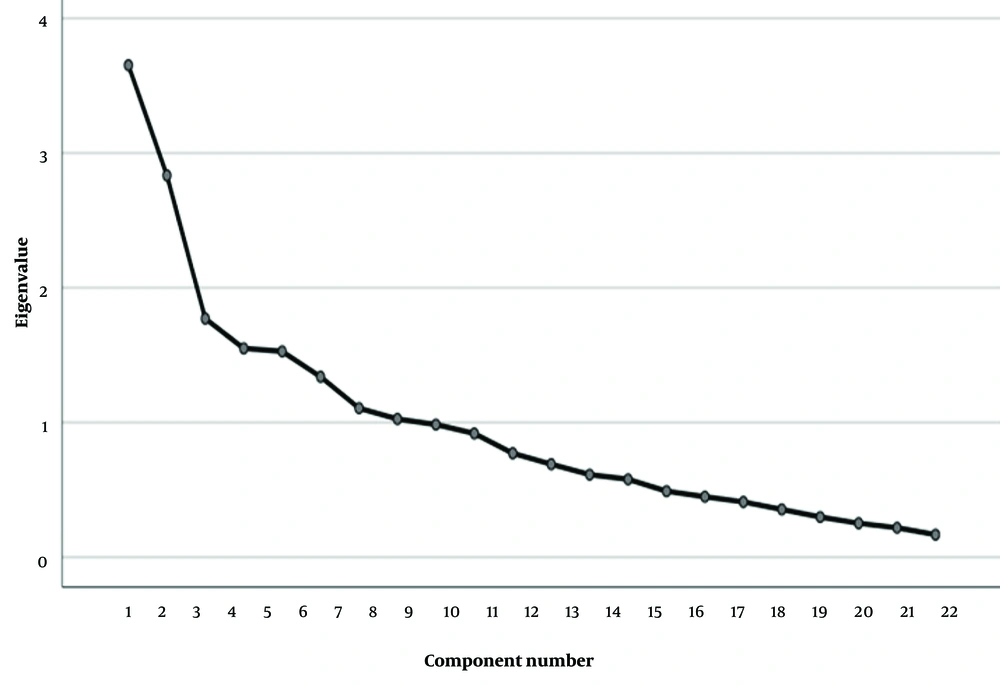

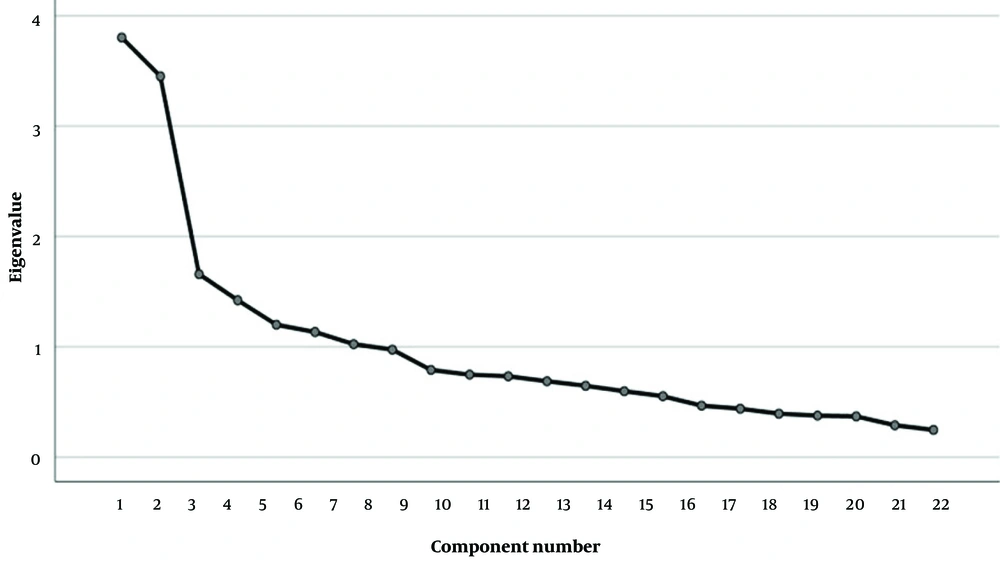

The adequacy of sampling was measured using the KMO coefficient, which was found to be 0.71 for the age group below 12 years and 0.68 for the age group above 12 years. Additionally, the Bartlett's sphericity test was significant (P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001). The results obtained from both the Kaiser criterion and the scree plot (Figures 1 and 2) indicated that the questionnaire has eight factors for people over 12 years old, with a variance of 62.2%. On the other hand, Figure 2 suggested that the questionnaire has seven factors for people under 12 years old, with a variance of 67.7%. Factor analysis was conducted to determine whether the items relating to oral problems and risk factors associated with oral health create different domains.

Using factor analysis, 8 components were extracted for children under 12 years old and 7 components for those over 12 years old. The factor loadings of the items are provided in Tables 5 and 6. The majority of item factor loadings in the first two components exceeded 0.35 for both age groups. A different factor loading sign was observed for the items with a negative correlation. After examining the factor loadings, it became clear that the two domains, namely mouth and gum (oral) problems and risk factors related to oral health, were not well-explained. This issue may be due to the fact that the answer options for these questions do not follow the same Likert scale.

| Variables | Component | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| How would you describe the health of your teeth and gums? | -0.566 | 0.449 | 0.178 | -0.217 | -0.057 | 0.181 | -0.003 | -0.129 |

| How often during the past 12 months did you have toothache or feel discomfort due to your teeth? | 0.558 | -0.293 | -0.003 | 0.203 | -0.086 | 0.141 | -0.451 | 0.056 |

| How often did you go to the dentist during the past 12 months؟ | -0.101 | 0.018 | 0.466 | 0.293 | 0.397 | -0.214 | -0.269 | 0.200 |

| What was the reason for your last visit to the dentist? | -0.464 | 0.272 | 0.315 | 0.172 | -0.171 | 0.010 | 0.351 | 0.278 |

| How often do you clean your teeth? | -0.413 | 0.482 | 0.263 | 0.025 | -0.066 | 0.167 | -0.091 | 0.337 |

| Do you use toothpaste to clean your teeth? | 0.243 | 0.073 | 0.067 | 0.221 | -0.265 | 0.449 | 0.189 | -0.489 |

| Do you use toothpaste that contains fluoride? | -0.132 | 0.151 | 0.566 | 0.085 | -0.113 | 0.501 | 0.110 | -0.102 |

| I am not satisfied with the appearance of my teeth | 0.323 | -0.362 | 0.227 | 0.376 | 0.012 | -0.225 | 0.259 | 0.080 |

| I often avoid smiling and laughing because of my teeth | 0.158 | -0.537 | 0.538 | 0.012 | 0.106 | -0.051 | -0.085 | -0.219 |

| Other children make fun of my teeth | 0.169 | 0.030 | 0.270 | 0.246 | 0.326 | -0.371 | 0.391 | -0.360 |

| Toothache or discomfort caused by my teeth forced me to miss classes at school or miss school for whole days | 0.199 | -0.383 | 0.453 | -0.225 | -0.307 | 0.017 | -0.404 | -0.137 |

| I have difficulty biting hard foods | 0.461 | -0.451 | 0.037 | -0.053 | 0.208 | 0.309 | 0.357 | 0.254 |

| I have difficulty in chewing | 0.470 | -0.391 | 0.019 | -0.061 | -0.236 | 0.364 | 0.135 | 0.355 |

| How often do you eat or drink any of the following foods, even in small quantities? Fresh fruit | -0.078 | 0.297 | 0.190 | 0.042 | 0.604 | 0.349 | -0.238 | -0.111 |

| Biscuits, cakes, cream cakes, sweet pies, buns etc0. | 0.462 | 0.245 | 0.100 | -0.529 | 0.241 | 0.010 | 0.136 | -0.042 |

| Lemonade, Coca Cola or other soft drinks | 0.358 | 0.092 | 0.376 | -0.588 | -0.032 | -0.129 | 0.158 | 0.140 |

| Jam/honey | 0.446 | 0.357 | -0.173 | 0.420 | 0.272 | 0.312 | 0.007 | 0.062 |

| Chewing gum containing sugar | 0.391 | 0.526 | 0.212 | -0.087 | -0.280 | -0.235 | -0.026 | -0.085 |

| Sweets/candy | 0.598 | 0.327 | -0.071 | -0.328 | 0.349 | 0.066 | -0.013 | -0.017 |

| Milk with sugar | 0.467 | 0.456 | 0.153 | 0.235 | -0.467 | -0.139 | -0.012 | 0.001 |

| Tea with sugar | 0.565 | 0.445 | -0.290 | 0.062 | -0.124 | -0.002 | -0.043 | -0.129 |

| Coffee with sugar | 0.568 | 0.463 | 0.184 | 0.228 | 0.025 | -0.164 | -0.109 | 0.266 |

a Extraction method: Principal component analysis.

| Variables | Component | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| How would you describe the health of your teeth and gums? | -0.650 | 0.403 | 0.072 | 0.304 | -0.084 | 0.066 | 0.039 |

| How often during the past 12 months did you have toothache or feel discomfort due to your teeth? | 0.577 | -0.400 | 0.102 | -0.169 | -0.248 | -0.080 | -0.106 |

| How often did you go to the dentist during the past 12 months | 0.222 | 0.078 | 0.357 | 0.173 | -0.532 | 0.281 | 0.169 |

| What was the reason for your last visit to the dentist? | -0.377 | 0.137 | 0.012 | 0.534 | 0.200 | 0.212 | 0.185 |

| How often do you clean your teeth? | -0.385 | 0.086 | 0.639 | 0.162 | 0.005 | -0.046 | 0.035 |

| Do you use toothpaste to clean your teeth | -0.264 | -0.174 | 0.643 | -0.180 | 0.007 | 0.136 | -0.108 |

| Do you use toothpaste that contains fluoride? | -0.181 | -0.065 | 0.590 | -0.446 | 0.007 | 0.251 | -0.087 |

| am not satisfied with the appearance of my teeth | 0.379 | -0.392 | 0.201 | -0.118 | 0.422 | -0.206 | 0.050 |

| I often avoid smiling and laughing because of my teeth | 0.434 | -0.462 | 0.149 | 0.032 | 0.495 | 0.174 | 0.107 |

| Other children make fun of my teeth | 0.433 | -0.238 | 0.143 | 0.408 | 0.376 | 0.166 | 0.162 |

| Toothache or discomfort caused by my teeth forced me to miss classes at school or miss school for whole days | 0.540 | -0.254 | 0.086 | 0.435 | -0.271 | -0.028 | -0.015 |

| I have difficulty biting hard foods | 0.483 | -0.325 | 0.199 | 0.011 | -0.252 | -0.204 | -0.025 |

| I have difficulty in chewing | 0.580 | -0.404 | 0.049 | 0.292 | -0.166 | 0.011 | 0.006 |

| How often do you eat or drink any of the following foods, even in small quantities? Fresh fruit | -0.255 | 0.323 | 0.390 | 0.177 | 0.064 | -0.558 | 0.289 |

| Biscuits, cakes, cream cakes, sweet pies, buns etc0. | 0.331 | 0.443 | -0.039 | -0.373 | -0.047 | -0.087 | 0.484 |

| Lemonade, Coca Cola or other soft drinks | 0.465 | 0.522 | 0.027 | 0.022 | -0.022 | 0.205 | 0.295 |

| Jam/honey | 0.215 | 0.513 | 0.122 | 0.198 | 0.045 | -0.305 | -0.479 |

| 11) Chewing gum containing sugar | 0.371 | 0.438 | 0.149 | 0.141 | 0.090 | -0.315 | -0.223 |

| 11) Sweets/candy | 0.453 | 0.571 | 0.124 | -0.184 | 0.134 | -0.104 | 0.177 |

| Milk with sugar | 0.344 | 0.520 | 0.054 | -0.038 | 0.198 | 0.260 | -0.375 |

| Tea with sugar | 0.449 | 0.570 | -0.030 | -0.052 | -0.064 | 0.020 | 0.077 |

| Coffee with sugar | 0.351 | 0.597 | 0.056 | 0.057 | 0.037 | 0.375 | -0.158 |

a Extraction method: Principal component analysis.

5. Discussion

The present study assessed the validity and reliability of the WHO-OHSQ questionnaire for children and adolescents after translation and back-translation. The questionnaire demonstrated clarity and fluency, and its results were consistent when repeated under the same conditions. Cronbach's alpha analysis indicated an acceptable level of internal consistency and reliability. The questionnaire was multifactorial, and the concurrent validity survey showed that only four questions had a significant relationship with the three additional questions.

In this study, all the questions were initially translated into Persian. After translating and back-translating the fourteen questions, no differences were found between the parallel translations. Due to cultural differences and disagreements with the Education Department, the question about smoking was removed from the questionnaire. In the pilot phase, it was observed that individuals who read the questionnaire for the first time had difficulty understanding the difference between rural, urban, and peri-urban areas. Therefore, the location question was modified to two choices: Rural and urban. These modifications were also observed in other studies (17).

The internal consistency of the WHO-OHSQ questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach's alpha coefficient. The results showed a value of 0.656 for students under 12 years old and 0.643 for students over 12 years old. It was also shown that this value remained higher than 0.6 if any of the questionnaire items were removed. When the internal correlation of a question is low, Cronbach's alpha decreases. If the low value of Cronbach's alpha is due to the internal correlation of the question, one solution is to modify the questionnaire by removing the questions that do not have a significant impact on its value. Also, it is important for the questions of the questionnaire to follow the same Likert scale, which was not observed in this questionnaire (26). However, studies suggest that a Cronbach's alpha of 0.6 or higher is acceptable for this age group (17, 27-29). Therefore, it can be concluded that the internal consistency of the questionnaire is acceptable.

A similar study was conducted on the Arabic version of the index, with an average age of 16 ± 1.04 (adolescent group), which resulted in a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.72. This value is borderline and close to the value obtained in our study (16). In the Chilean language version, with an average age of 12 years (children's group), an alpha value of 0.62 was obtained for this index, confirming the results of our study (17). In addition, the internal consistency of binary answer questions was measured using the Kuder-Richardson-20 index. The calculated value was 0.39 for participants under the age of 12 and 0.376 for those over the age of 12, which, according to the range between 0 - 1 for this index, is an intermediate value. In the Chilean version of the study, the Kuder-Richardson-20 index was equal to 0.2 (14).

The reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated using the test-retest method. The results demonstrated that the questionnaire produced consistent scores for individuals over time. The ICC coefficient for the questionnaire was found to be between 0.81 and 0.97 for both age groups. When the coefficient is above 0.9, it is considered very excellent, and between 0.8 and 0.9 is excellent (26). Our Arabic counterpart's coefficient was found to be 0.89 on average, which confirms our study's results (16). In a study conducted on the Chilean version of the questionnaire, the ICC coefficient was not calculated (17).

During the examination of the relationship between the questionnaire's main question and three additional questions, it was discovered that describing oral health, the number of times feeling toothache in the last 12 months, and problems related to biting and chewing are significantly related to their corresponding questions. However, questions related to nutrition, which are associated with oral health risk factors, do not show any significant relationship with these three additional questions. Since most participants in the study had good oral health and brushing habits, these results could be influenced by their good dental health. It should be mentioned that in none of the studies concerning this questionnaire has the validity been measured while adding questions. However, in other validation-related studies, the validity has been determined by comparing the questionnaire's questions with a gold standard question (30).

The exploratory factor analysis showed that the KMO index value was 0.71 for children under 12 years old and 0.68 for those over 12 years old. These values are considered acceptable for conducting the exploratory factor analysis (31). After conducting a conventional varimax rotation, seven factors were identified for the age group below 12 years, while eight factors were identified for the age group above 12 years. This indicates that oral problems and risk factors related to oral health cannot be easily classified into two separate domains. The results also indicate that this tool can be multidimensional. Generally, including more questions in the tool can lead to a more accurate measurement of a dimension. The results of a study conducted in Chile confirmed the findings of our study. However, in a study that focused on the Arabic version of the tool, factor analysis was not performed (13, 14).

Due to the spread of the Coronavirus disease, it was not possible to measure a gold standard along with the questionnaire to compare its results. It is recommended that future studies use the objective criterion DMFT to check the correlation between DMFT and questionnaire questions. Also, information was collected online during the school holidays, which naturally limits the study's population to those who have access to the internet. It is suggested that the results of this study be re-evaluated by referring to schools for future studies. Another limitation of this study was not using a standard measure such as the quality of life score related to oral health to measure concurrent validity. To measure the concurrent validity, it is suggested to measure the relationship between the quality of life score related to oral health and the questionnaire questions on a smaller number of people. However, one of the strengths of this study was its large sample size, which can confirm the accuracy of the analysis performed.

5.1. Conclusions

The Persian version of the WHO-OHSQ, designed for children and adolescents, is a reliable questionnaire over time. If the questionnaire is repeated and the responses from individuals in the same population are collected, it yields similar results. It has internal consistency, but it is a multi-factor questionnaire. Along with clinical studies, it can provide information about a person's oral health habits, chewing and biting problems, satisfaction with the appearance of teeth, and other related factors.