1. Background

Food security is considered a universal public health challenge, especially for children, because it affects their physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional development and has long-term negative consequences (1, 2). Food insecurity is characterized by limited or uncertain availability of nutritious and safe foods or by a limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways (3, 4). It is especially prevalent among low-income families with children (5). Food insecurity in Iranian households with children is proportionally high, as confirmed by previous reports (6-8). Even if children do not eat less, they may still suffer from poor nutrition or consume lower-quality food because food-insecure households with tight budgets often purchase cheaper, energy-dense foods (9, 10). According to previous evidence, food insecurity may impact children's healthcare utilization, leading to higher hospitalization rates and healthcare expenditures compared to food-secure households (5, 11).

Nutritional status significantly impacts children's growth during sensitive periods. Early weight and height development are widely acknowledged to significantly affect health quality later in life (12). Children need more energy and nutrients, such as zinc and iron, to sustain adequate growth (13). Household food insecurity is linked to protein-energy malnutrition manifestations in children, including wasting, stunting, and underweight, especially in developing countries (1). The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified underweight as the most significant risk factor contributing to the global burden of disease in developing countries (14). In nations with high child mortality, food insecurity results in nearly 15 percent of the total disability-adjusted life years (DALY) losses (15, 16). Although previous literature has assessed the association of household food insecurity with nutritional outcomes among children, the findings are inconsistent across different study populations. In a study, the prevalence of food insecurity among 300 subjects in Tabriz was 36.3%, with significant determinants being employment status, education, income, and family size (17). In another study by Farhangi et al., the prevalence of food insecurity was 36%, and it was associated with body mass index, male gender, and income (6). A study among households with schoolchildren in southeastern Iran reported a prevalence of food insecurity at 42.3%, which was associated with household size, the number of children per household, parents' education levels, father's occupation status, and household income (18).

2. Objectives

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the prevalence of food insecurity and the association of household food insecurity with nutritional outcomes among children aged 2 - 5 years old residing in urban and rural areas of Khalkhal City, Iran.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

The present study was a cross-sectional study conducted on 300 Iranian children aged 2 - 5 years old who were referred to urban and rural healthcare centers between November 2021 and March 2022. Subjects were included in the survey using multi-stage cluster sampling. The inclusion criteria included the willingness of parents to participate in the study and children of both sexes between 2 and 5 years old. The exclusion criteria included having specific diseases from birth (such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, kidney, and liver disorders), low birth weight (LBW), incomplete demographic or anthropometric information, and the inability of the child's parents to answer the questions of the questionnaire. Based on previous reports (19), considering 95% power and an α of 5%, a sample of 300 Iranian children aged 2 - 5 years old was selected from those referring to healthcare centers.

The research protocol was in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee in Research of Khalkhal University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (Ethical code: IR.KHALUMS.REC.1400.002, Approval date: 2021-07-10). Informed consent was obtained from all the mothers, and a fingerprint was obtained from illiterate mothers at the beginning of the study.

3.2. Data Collection and Questionnaires

Socioeconomic and demographic information, including age, gender, parents’ education (illiterate-elementary, high school, or college), parents’ job (unemployed, laborer, freelance, government employee, private employee), race, type of residence (urban or rural), number of family members, owner status (landlord or tenant), type of house (villa or apartment), and income (million tomans), were obtained through questionnaires administered by interviewers. The participants' mothers filled out the questionnaire.

Household food security status was assessed using the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 18-item food security questionnaire (20), a standard tool previously validated in Iran (21, 22). The USDA household food security questionnaire has two sections: The first section is for all households (questions 1 to 10), and the second section is completed for households with children under the age of 18 years (questions 11 to 18). The food insecurity score was generated by determining whether questions were answered "sometimes" or "often" with a value of 1 and "never" with a value of 0. Families with a total score of 0 - 2 are considered food secure, scores of 3 - 7 indicate food insecurity without hunger, scores of 8 - 12 indicate food insecurity with moderate hunger, and scores greater than 13 indicate food insecurity with severe hunger.

3.3. Measurement of Anthropometric Indices

In the current study, weight was measured using a digital scale made in Japan with an accuracy of 0.1 kg, without shoes and with the least possible clothing. A tape measure with an accuracy of 0.5 cm was used to measure height in a standing position. During the anthropometric measurements, participants wore light clothes and took off their shoes (23). Weight-for-age (WAZ) and height-for-age (HAZ) Z scores were used to evaluate growth status in this study.

A child is considered underweight when they are either thin or short for their age, which is caused by a combination of chronic and acute malnutrition. Stunted growth describes children who are short for their age but not necessarily thin, and it is caused by chronic malnutrition. Underweight and stunting among children were defined as WAZ and HAZ less than 2 standard deviations (Z score < -2SD) below the median of the reference population (growth references, WHO 2007), respectively. The definition of overweight and obesity was based on WAZ exceeding two standard deviations above the median of the reference population (12, 24).

3.4. Statistical Analysis

In this study, the normal distribution of the data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistical test. ANOVA with Post hoc (LSD) was used to compare quantitative variables across quartiles of food insecurity scores, and the chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables. The correlation between the food insecurity score (independent variable) and type of weight (dependent variable) was evaluated using the Spearman test (without adjustment), the partial test adjusted for age and sex, and the partial test adjusted for age, sex, mother's and father's education, race, father's and mother's job, type of residence, number of family members, owner status, type of house, and income. The association between the food insecurity score (independent variable) and anthropometric indices, including weight and height (dependent variables), was assessed using linear regression analysis in three models: Model 1, without adjustment; model 2, linear regression analysis adjusted for age and sex; model 3, linear regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, mother's and father's education, race, father's and mother's job, type of residence, number of family members, owner status, type of house, and income. Odds ratios (95% CI) for stunting according to the food insecurity score were estimated using multivariable logistic regression in three models: Model 1, unadjusted; model 2, adjusted for age and sex; model 3, adjusted for age, sex, mother's and father's education, race, father's and mother's job, type of residence, number of family members, owner status, type of house, and income. All quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and qualitative data are expressed as numbers (percentages). SPSS version 19 software was used for data analysis. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

4. Results

The characteristics of subjects across quartiles of food insecurity scores are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 3.77 ± 0.97 years. Of the 300 participants studied, 159 (53%) were girls. In the present study, 39% of participants had food security, and the prevalence of food insecurity without hunger, food insecurity with moderate hunger, and food insecurity with severe hunger were 22.3%, 23%, and 15.7%, respectively. Across quartiles of food insecurity scores, significant differences were observed regarding the mother's education, father's education, race, father's job, mother's job, type of weight, income, and owner status (P for all < 0.001), as well as type of house (P = 0.001) and type of residence (P = 0.001). Compared to quartile 1, those in quartile 4 had lower income (P < 0.001).

| Characteristics | Food Insecurity Quartiles | P-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (N = 67) | Q2 (N = 91) | Q3 (N = 69) | Q4 (N = 73) | Total (N = 300) | ||

| Food insecurity score | 0.00 ± 0.00 a,b,c | 2.26 ± 1.24 d,e | 8.01 ± 1.64 f | 13.50 ± 1.74 | 5.81 ± 5.36 | < 0.001 a |

| Type of food insecurity (N) | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Food security | 67 (57.3) | 50 (42.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 117 (39.0) | |

| Food insecurity without hunger | 0 (0.0) | 41 (61.2) | 26 (38.8) | 0 (0.0) | 67 (22.3) | |

| Food insecurity with moderate hunger | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 43 (62.3) | 26 (37.7) | 69 (23) | |

| Food insecurity with severe hunger | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 47 (100.0) | 47 (15.7) | |

| Age (y) | 3.71 ± 1.00 | 3.97 ± 0.99 | 3.59 ± 1.01 | 3.73 ± 0.88 | 3.77 ± 0.97 | 0.09 a |

| Sex | 0.37 b | |||||

| Boy | 27 (19.1) | 43 (30.5) | 38 (27.0) | 33 (23.4) | 141 (47.0) | |

| Girl | 40 (25.2) | 48 (30.2) | 31 (19.5) | 40 (25.2) | 159 (53.0) | |

| Mother's education | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Illiterate-elementary | 9 (14.8) | 17 (27.9) | 10 (16.4) | 25 (41.0) | 61 (20.3) | |

| High-school | 26 (21.3) | 32 (26.2) | 25 (20.5) | 39 (32.0) | 122 (40.7) | |

| College | 32 (27.4) | 42 (35.9) | 34 (29.1) | 9 (7.7) | 117 (39.0) | |

| Father's education | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Illiterate-elementary | 0 (0.0) | 5 (13.9) | 11 (30.6) | 20 (55.6) | 36 (12.0) | |

| High-school | 25 (16.7) | 45 (30.0) | 31 (20.7) | 49 (32.7) | 150 (50.0) | |

| College | 42 (36.8) | 41 (36.0) | 27 (23.7) | 4 (3.5) | 114 (38.0) | |

| Race | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Persian | 3 (10.3) | 7 (24.1) | 13 (44.8) | 6 (20.7) | 29 (9.7) | |

| Turkish | 60 (27.3) | 67 (30.5) | 37 (16.8) | 56 (25.5) | 220 (73.3) | |

| Kurdish | 4 (7.8) | 17 (33.3) | 19 (37.3) | 11 (21.6) | 51 (17.0) | |

| Father's job | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Unemployed | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (44.4) | 5 (55.6) | 9 (3.0) | |

| Labor | 14 (17.1) | 18 (22.0) | 19 (23.2) | 31 (37.8) | 82 (27.3) | |

| Freelance | 25 (21.7) | 37 (32.2) | 24 (20.9) | 29 (25.2) | 115 (38.3) | |

| Government employee | 25 (35.7) | 32 (45.7) | 12 (17.1) | 1 (1.4) | 70 (23.3) | |

| Private employee | 3 (12.5) | 4 (16.7) | 10 (41.7) | 7 (29.2) | 24 (8.0) | |

| Mother's job | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Student | 1 (6.7) | 8 (53.3) | 3 (20.0) | 3 (20.0) | 15 (5.0) | |

| Housekeeper | 47 (19.7) | 71 (29.7) | 52 (21.8) | 69 (28.9) | 239 (79.7) | |

| Government employee | 19 (57.6) | 11 (33.3) | 3 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (11.0) | |

| Private employee | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 11 (84.6) | 1 (7.7) | 13 (4.3) | |

| Type of residence | 0.001 b | |||||

| Urban | 44 (25.9) | 60 (35.3) | 38 (22.4) | 28 (16.5) | 170 (56.7) | |

| Rural | 23 (17.7) | 31 (23.8) | 31 (23.8) | 45 (34.6) | 130 (43.3) | |

| Number of family members | 0.07 b | |||||

| 2 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1(100) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| 3 | 19 (19.0) | 22 (22.0) | 23 (23.0) | 36 (36.0) | 100 (33.3) | |

| 4 | 34 (23.9) | 46 (32.4) | 34 (23.9) | 28 (19.7) | 142 (47.3) | |

| 5 | 11 (25.6) | 16 (37.2) | 10 (23.3) | 6 (14.0) | 43 (14.3) | |

| 6 | 3 (21.4) | 7 (50.0) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (21.4) | 14 (4.7) | |

| Type of height | 0.07 b | |||||

| Normal | 48 (24.0) | 54 (27.0) | 53 (26.5) | 45 (22.5) | 200 (66.7) | |

| Stunt | 19 (19.0) | 37 (37.0) | 16 (16.0) | 28 (28.0) | 100 (33.3) | |

| Height (m) | 0.98 ± 0.11 | 0.99 ± 0.11 | 0.99 ± 0.11 | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 0.98 ± 0.11 | 0.58 a |

| Type of weight | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Underweight | 9 (18.0) | 26 (52.0) | 5 (10.0) | 10 (20) | 50 (16.7) | |

| Normal | 51 (22.3) | 52 (22.7) | 63 (27.5) | 63 (27.5) | 229 (76.3) | |

| Overweight | 7 (33.3) | 13 (61.9) | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (7.0) | |

| Weight (kg) | 15.18 ± 3.32 | 15.09 ± 3.18 | 14.79 ± 2.69 | 14.58 ± 2.24 | 14.91 ± 2.90 | 0.57 a |

| Owner status | < 0.001 b | |||||

| Landlord | 50 (27.6) | 68 (37.6) | 35 (19.3) | 28 (15.5) | 181 (60.3) | |

| Tenant | 17 (14.3) | 23 (19.3) | 34 (28.6) | 45 (37.8) | 119 (39.7) | |

| Type of house | 0.001 b | |||||

| Villa | 24 (14.1) | 56 (32.9) | 42 (24.7) | 48 (28.2) | 170 (56.7) | |

| Apartment | 43 (33.1) | 35 (26.9) | 27 (20.8) | 25 (19.2) | 130 (43.3) | |

| Income (million toman) | 8.70 ± 5.09 a,b, c | 6.41 ± 4.19 e | 5.51 ± 1.90 | 4.79 ± 1.78 | 6.32 ± 3.82 | < 0.001 a |

a Significant difference between 1 compared to 2.

b Significant difference between 1 compared to 3.

c Significant difference between 1 compared to 4.

d Significant difference between 2 compared to 3.

e Significant difference between 2 compared to 4.

f Significant difference between 3 compared to 4.

g Values are expressed as No. (%) or Mean ± SD.

h From ANOVA for quantitative variables; Chi-square for qualitative variables; Post hoc (LSD) according to the following pattern.

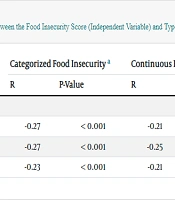

The correlation between the food insecurity score (independent variable) and type of weight (dependent variable) is shown in Table 2. In all models, categorized and continuous food insecurity scores correlated negatively with type of weight (P for all < 0.001). The food insecurity score (independent variable) didn’t show any significant association with anthropometric indices, including weight and height (dependent variables) (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

Odds ratios (95% CI) for stunting according to the food insecurity score are shown in Table 4. Food insecurity couldn’t predict the risk of stunting in all subjects before and after adjustment (P > 0.05).

a Categorized food insecurity: Food security, food insecurity without hunger, food insecurity with moderate hunger, and food insecurity with severe hunger. Type of weight: Underweight, normal, and overweight.

b P < 0.05 was considered as significant. R was considered as correlation coefficient.

c Correlation and significant with the Spearman test (without adjustment).

d Correlation and significant with the Partial-test along with the adjustment of age and sex.

e Correlation and significant with the Partial-test along with the adjustment of age, sex, mother's and father's education, race, father's and mother's job, type of residence, number of family members, owner status, type of house, and income.

a P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

b linear regression analysis without adjustment.

c linear regression analysis with adjustment for age and sex.

d linear regression analysis with correction for age, sex, mother's and father's education, race, father's and mother's job, type of residence, number of family members, owner status, type of house, and income.

| Variables | Or (CI) | B | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous food insecurity score | |||

| Model 1 b | 1.008 (0.96 - 1.05) | 0.008 | 0.72 |

| Model 2 c | 1.01 (0.96 - 1.05) | 0.01 | 0.65 |

| Model 3 d | 0.98 (0.92 - 1.04) | -0.01 | 0.53 |

| Quartiles of food insecurity | |||

| Model 1 b | 1.04 (0.84 - 1.30) | 0.04 | 0.68 |

| Model 2 c | 1.05 (0.84 - 1.32) | 0.05 | 0.62 |

| Model 3 d | 0.92 (0.68 - 1.32) | -0.08 | 0.58 |

a P < 0.05 statistically significant by Multivariable logistic regression.

b unadjusted.

c adjusted for age and sex.

d adjustment for age, sex, mother's and father's education, race, father's and mother's job, type of residence, number of family members, owner status, type of house, and income.

5. Discussion

Food security is considered a universal public health challenge, especially in children, because it affects their current physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional development and has long-term negative consequences (1, 2). Household food insecurity is linked to manifestations of protein-energy malnutrition in children, including wasting, stunting, and underweight, particularly in developing countries (1).

In the present study conducted in Ardabil province, a semi-developed province in north-west Iran, 61% of households experienced some degree of food insecurity. Various reports from different regions of Iran show differing rates of food insecurity based on the developmental conditions of the regions studied. For example, the prevalence of household food insecurity was 37.8% in Tehran (25), the capital of Iran, in 2019, 33.4% in Esfahan (26), a developed province in Iran, in 2017, and 32.9% in Yazd (27), an industrial city in central Iran, in 2007. Studies conducted in less developed regions of Iran, including Zabol (18) and Zahedan (28, 29), reported higher prevalence rates of food insecurity (42% in Zabol in 2019, 58.8% in Zahedan in 2017, and 66% in Zahedan in 2022), which are comparable to or lower than the rate found in our study. The high food insecurity rate in our study population may be due to recent unprecedented inflation and a dramatic increase in the cost of food items in Iran. It should also be noted that in the studies cited above, food insecurity was not measured using the same module, and the sociodemographic characteristics (such as place of residence and parents’ education) of the studied households were not the same.

We found that in the subgroup of our study sample with the highest food insecurity score (quartile 4), family income was significantly lower compared to those with the lowest food insecurity score (quartile 1). The average family income in quartile 4 was remarkably lower than the current poverty threshold for a four-person family in Iran. Several studies in both developing and developed countries have indicated that economic poverty is closely related to elevated levels of food insecurity, and the incidence of food insecurity increases as the income-to-needs ratio decreases (28, 30-33). Findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) also confirmed this relationship (34). A study in Canada found evidence that improvements in family income and employment reduce household food insecurity, indicating the potential for income- and employment-based policy strategies to strengthen household food security for low-income families (35). Another study conducted in southern Ethiopia documented that income inequality exacerbates the food insecurity of families, with food-insecure households having significantly higher income inequality (Gini coefficient) than those who were food-secure (36). In Iran, Majdizadeh et al. showed a significant positive relationship between poverty and food insecurity in children aged 2 - 5 years (37). Moreover, a large sample study in Tehran identified economic status as the key determinant of food security, with approximately 63% of the poorest families being food insecure (25). Destitution affects the amount and quality of food each family member consumes, and when family income declines, food insecurity intensifies. Parents' education and employment, particularly the head of the household, can contribute to improving food security by increasing household income levels.

Research on the association between food insecurity and undernutrition complications in children has produced mixed results. In the present study, statistically significant and negative correlations were observed between household food insecurity and type of weight (underweight, normal, and overweight) among children aged 2 - 5 years old. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated a significant relationship between food insecurity and underweight in children (16, 38-43). Previously, in Iran, Abdurahman et al. also found that household food insecurity was significantly predictive of underweight among children aged 24 - 59 months (44). Hasan et al. showed that household food insecurity increases the risk of different forms of undernutrition, including underweight and wasting, among children under the age of 5 years in Bangladesh (45). In Colombia, Hackett et al. reported that food-insecure preschool children were three times as likely to be underweight as food-secure children (4). Several reasons for these relationships have been proposed, including decreased dietary intakes, a reduction in portion size, frequency of meals, and dietary variety as consequences of household food insecurity (1). However, some studies conducted in Nepal (46) and the United States (47) reported that either household or child food insecurity was not related to underweight in children aged 6 to 23 months and less than 4 years, respectively.

In the present study, household food insecurity couldn’t predict the risk of stunting among children aged 2 - 5 years old. Our findings are in line with the findings of some previous studies. A study in Colombia showed stunting had no association with food insecurity among preschool children (4). Drennen et al. also reported similar findings in children under the age of 4 years in the United States (47). Another study on children under 5 years in Ethiopia showed that food insecurity had an association with being underweight, but not with stunting and wasting (48). The negative association between household food insecurity and type of weight and the lack of relationship between food insecurity and child stunting in our study may suggest that the households’ short-term experience of food insecurity within 30 days before the survey was not enough to cause chronic malnutrition and stunting in children. Underweight is more affected by recent nutritional status. In other words, a reduction in the child’s weight, generally seen as a rapid response to inadequate energy intake, is thought to precede decreases in height. Linear growth occurs much slower than weight gain in children, and stunting may be associated with prolonged micronutrient (especially calcium, zinc, iodine, vitamin D, vitamin A, etc.) or macronutrient (especially protein) deficiency. Additionally, the rate of height growth in children is affected by other factors such as birth length and genetic potential (49, 50).

Conversely, the results of a study by Majdizadeh et al. in Hamedan City, Iran, showed that food insecurity was significantly related to the Z-score for height-for-age among 2- to 5-year-old urban and rural children (37). Tiwari et al. also revealed a strong association between household food insecurity and stunting and severe stunting among children under the age of 5 and 2 years, respectively (51). In Pakistan, families that experienced food insecurity with hunger were three times as likely to have a stunted child (52).

Overall, the controversial findings achieved in different investigations appear to be partly due to different modules used to measure household food insecurity, criteria used to determine children’s growth status, studies’ sample sizes and age groups, and non-nutritional factors.

5.1. Limitation and Recommendation

Our study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the study did not allow us to examine the causality between household food insecurity and complications of undernutrition in children. Second, the use of different modules for measuring food insecurity and criteria for child nutritional status in various studies presents a major gap in the comparability of these findings. Third, we didn’t assess the wasting index, an important complication of undernutrition that refers to low weight for height. Finally, the small sample size is another limitation of our study that should be considered in future research.

5.2. Conclusions

In the current study, we illustrate that Iranian families with the lowest income had the highest food insecurity scores. Household food insecurity was negatively correlated with the type of weight among children aged 2 - 5 years old, while it was not associated with stunting. Designing and implementing interventions to increase family income and food security by policymakers may lead to improvements in indices of undernutrition in children.