1. Context

A hundred years ago, death was considered a natural and accepted part of family life. However, children currently grow up in a culture that avoids grief and sadness (1). While today, mourning has become a common experience in children, and at some point in their childhood, the vast majority of children will experience the death of a close family member or friend; approximately 1 in 20 children in the United States experiences the death of a parent by the age of 16. To the extent that even in scientific research, the issue of grief in children is considered taboo. Studies of children's perceptions of death began in the 1940s (2). Early definitions and official classifications (ICD and DSM) recognized grief reactions as disorders requiring medical advice. However, this issue has changed in recent versions (3). In DSM-5, “uncomplicated grief” is mentioned as an unclassified condition (4), which should be differentiated from major depression (5). Moreover, DSM-5 has introduced the term prolonged grief disorder and ICD-11 has classified it as long-term grief disorder (2) and defined it as an intense longing for the deceased and the symptoms of grief including extreme sadness, guilt, preoccupation with the deceased loved one, avoiding remembering the loss, aggressiveness, and difficulty in trusting (6). Complicated grief can last longer than usual or expected (7) and may be developed by several factors that interfere with the grief process. These factors can include the type of relationship between the child and the deceased, the circumstances surrounding the death, and the lack of a grief support system (1).

1.1. Children’s Perception of Death

Children gradually acquire five concepts for understanding and coping with death: Irreversibility (permanence of death), individuals’ death (death comes even to the individual himself/herself), universality (death is unavoidable), inoperability (cutting off all life functions), and causality (understanding the causes of death) (8, 9). Causality refers to knowing the cause of death. The development of the understanding of the cause of death occurs during the following stages: In stage one (2 - 3 years), children often have many questions about cemeteries, caskets, and funerals. However, for them, death is still considered a temporary phenomenon. The second stage (5 - 9 years) is when children pass from Piaget's pre-operational stage to the concrete operational stage (10) to recognize that death is an irreversible phenomenon (2). At this age, due to the presence of magical thinking, the child may think that their thinking and actions caused the death of their loved one, making them feel guilty (11). The third stage (+9 years) is when an individual perceives death as a personal, final, inevitable, and universal phenomenon (2). However, the individual still thinks that only very old and weak people die. At the age of adolescence, death is accepted as a natural process, but it is perceived as too far away, and it is not easy to accept that any accident may lead to death; this is why high-risk behaviors are often observed in adolescents (11). An accurate understanding of death usually develops at 9 to 11 years of age, although brain maturation and higher-order cognitive functioning continue to develop during adolescence and early adulthood (9). Finally, with the child's further development, his/her coping mechanisms become more effective and operational (12). Nevertheless, since grief occurs during development, there is always a part of the grieving process that may need to be resolved in the future (10). Black summarizes children's levels of perception of death and the symptoms of complicated grief as shown in Table 1 (1).

| Age (y) | Meaning of Death | Symptoms of Complicated Grief |

|---|---|---|

| 3 - 5 | Does not understand the permanence of death; repeatedly asks for the deceased person. | Anxiety, and regressive behaviors more than 6 months after the death |

| 6 - 8 | Understands death is permanent; assumes blame, and guilt for death. | School refusal; physical symptoms; suicidal thoughts; regressive behavior |

| 9 - 11 | Demands detailed information; increased expression of anger. | Shuning friends; increased moodiness 3 - 6 months after the death |

| 12 - 14 | Acts callous, indifferent, and egocentric; describes conversations with deceased. | School refusal; persistent depression, drug or alcohol use; associates with delinquents; precocious sexual behavior |

| 15 - 17 | Expresses thoughtfulness and empathy; feels overwhelmed by survivors’ emotional dependence and grief. | Mood swings; withdrawal from friends and group activities; poor school performance; high-risk behaviors, such as drug use |

1.2. Children's Reactions to Grief and Loss

Children do not "overcome" their grief but rather learn to live with the loss of their loved ones and adapt to it (13). The grief process of a child is not different from that of an adult. Children also go through the stages of denial, anger, and depression to accept the loss and grief, but there are minor differences in terms of behavior (14). For example, grief in children is considered intermittent (15), oscillating between short stages of extreme sadness and stages of apparently normal behavior. This stems from children's limited capacity to endure intense emotions for long periods and their inability to verbalize these experiences appropriately (9). Additionally, since children's speech ability is not yet fully developed, they have difficulty expressing their grief verbally (16) and prefer to express their feelings indirectly, mainly through games and drawings (17).

In general, a child's reaction to grief depends on several variables: Their relationship with the person who was lost, the reaction of other family members, the presence or absence of preparation for the event, the child's personality, mental resilience, and developmental stage or age (6). Behavioral disorders are also likely to occur in grieving children (18). Thus, a child known to be calm may exhibit delinquent and aggressive behaviors (19). Over time, childhood grief increases the child's sensitivity to problems with the law, school issues, and depression (20). Common and natural reactions of a grieving child include moodiness, crying or laughing without reason, destructive tendencies, isolation, developing phobias, behavioral regression, reduced school performance (21), and physical symptoms such as sleep problems, nocturia, loss of appetite, and anorexia (9).

Studies have shown that grieving children up to 2 years after the death of their parents have higher levels of disorders and emotional symptoms than non-grieving children (22). If grief counseling is not available during the formative years leading to adulthood, grieving children are more likely to develop psychophysical and socioeconomic consequences (9). Some reasons for not providing services to children include unrealistic public expectations, disagreements among mental health professionals about the need for services for grieving children, and the lack of information about the grief process in children (1).

Lewenberg and Goldring listed age-appropriate activities for dealing with grief:

- Children at the ages of 2 to 5 develop self-centered ways and magical thinking and are afraid to go to sleep when they are told that someone who has died has fallen asleep.

- Children from 6 to 9 years of age consider death to be a visit to heaven. Supportive activities include listing changes they can or cannot control, writing down how they see themselves and how others see them, and writing down their feelings.

- Restrictions should be placed on scary or disturbing games for children between the ages of 6 and 11. Parents should also consider taking time to read a book or pay attention to the child's feelings through games.

- Children between the ages of 12 and 18 can be encouraged to engage in discussions, express their frustrations through art, music, gardening, and sports, or handle their feelings of guilt, shame, embarrassment, or revenge as normal emotions (2).

The cause of death can have different effects on bereaved people. Those who lost someone to a sudden death reported more intense grief experiences, more complex grief symptoms, and less social acceptance of their experiences than those who lost someone to a "non-sudden" death, regardless of the type of death experienced. Specifically, unexpected death was associated with higher levels of abandonment, seeking an explanation for the loss, feelings of guilt and responsibility for the death, engaging in destructive behaviors, and shame. Sudden deaths interfere with the capabilities of the bereaved person (23, 24). Sudden and violent deaths usually include deaths from accidents, suicide, or murder. Any sudden loss makes it difficult for the relatives to understand the reality of the death of a close family member and prevents the bereaved relatives from saying their final goodbyes and performing the last services for that loved one. Furthermore, violent deaths can occur in gruesome ways, and relatives are helpless witnesses. After a sudden and violent death, the body may be severely mutilated or disfigured, which can prevent the body from being seen (24, 25).

While culture is recognized as an essential element of one's life, its impact is never more evident than when one is going through the grieving process. A family's culture can dictate established traditions for mourning. Some researchers argue that grief is not the same across cultures and that different groups experience different levels of emotional intensity (26, 27). People in some cultures tend to grieve more intensely and for longer (or less in some cultures) than many Europeans and Americans. Balinese people almost never look sad or upset in mourning and try to present a happy and smooth emotional appearance. In the United States, where there are thousands of cultures, there are significant cultural differences in mourning. For example, a large number of African Americans believe that whites grieve with much less intensity or display of emotion than Africans in the early stages of grief. European Americans often suppress mourning (28, 29).

2. Evidence Acquisition

The present study was a review-type design based on the review of the literature on Loss and bereavement in children, reactions and Effective interventions.

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Collection

The literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases, as well as in the Google Scholar search engine, up to December 2024. Relevant keywords and their combinations used for the literature search were as follows: Loss, bereavement, children.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria and Data Extraction

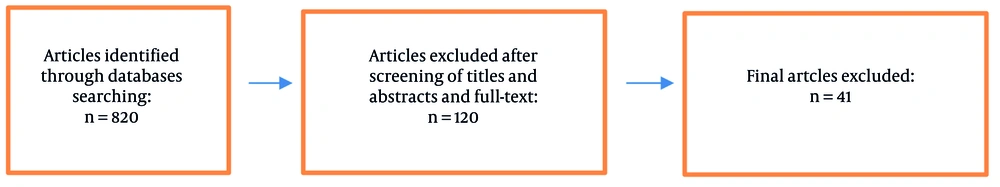

We included studies that examined grief and loss in children, children's reactions to grief, and effective interventions. A total of 820 articles were selected for further evaluation. After reviewing the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles and excluding irrelevant studies, 120 studies were selected for screening of titles and full-text review. Finally, 41 studies were included in the final review. The following data were extracted from eligible studies: Name of the first author, year of publication, study site, study population, number of participants in study groups, and interventions (Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. The Role of Nurses in Dealing with Grieving Children

The main key and one of the most effective treatments in grief interventions is to talk about the deceased's death and related feelings (30, 31). Given the high emotional load of grief, children may feel uncomfortable expressing their suffering. Thus, it is necessary to use verbal skills and counseling services along with other strategies and enjoyable and appropriate activities such as storytelling, games, collage making, diaries, drama, role-playing, book therapy, and all kinds of non-verbal activities that can help children express their feelings and thoughts about the death of their loved ones (6). Other supportive interventions in children's traumatic bereavement include cognitive behavioral therapy, developing coping skills, relaxing activities (yoga), and creative counseling techniques (expressing feelings or experiences through poems, drawings, singing, dancing, writing and drawing trauma narratives, epitaphs which are short texts performed in honor of a deceased person, holding a memorial service, holding a holiday program that focuses on helping the child cope with the grief during important family holidays) (26, 32-34). Finally, it is necessary to help children understand that seeking professional help does not indicate their weakness or mental illness, but rather it is a sign of their strength in recognizing pain and courage to move forward in life (6).

Depending on how the person copes with the death, grief consequences can be both positive and negative. Possible positive effects include personal growth, maturity, and a positive impact on the child's compassion. Negative consequences include temporary cognitive and emotional problems such as confusion, inability to focus on schoolwork, sleep disorders, and disturbing dreams, which may have serious consequences on school performance and career aspirations (20). It is very important to recognize the trauma experienced by grieving children (1). Thus, nurses can play an effective role in meeting the needs of the grieving child through the early implementation of a comprehensive assessment, management education about the benefits of grief support, initiating appropriate referrals, and providing grief support (1). Acknowledging the loss, active listening, and allowing family caregivers to express their feelings and tell their story are important ways that nurses can use (35).

There is a lack of evidence-based strategies to guide health professionals in providing optimal support during caregiver care and after a patient's death. There is evidence that the implementation of clinical guidelines, protocols, and tools facilitates improved care.

Part 1: Setting up the family caregiver support guide.

Part 2: Assessing the needs and creating a care guidance plan, conducting a needs assessment with family caregiver(s).

Part 3: Preparing dying instructions (if applicable, help family caregivers learn how to recognize signs of impending death and potential implications for the patient's care needs) (36).

Other recommendations for improving existing support for bereaved people include: Training and capacity building for current mental health workers, resource allocation and task sharing, prioritizing staff psychosocial well-being, increasing the provision and adaptation of services, including providing more resources and expanding national supports as well as regional services in areas with long waiting lists, and attention to the characteristics of interventions and support programs (37-39).

Unfortunately, it seems that nurses cannot spend as much time as grieving children need. Most baccalaureate nursing curricula have limited programs on pediatric grief. In addition, the lack of evidence-based guidelines has left nurses with inadequate tools and expertise to care for grieving children (20). Teaching nursing students about loss, grief, and bereavement should also be an interactive process to stimulate critical thinking and address the emotional domain of learning. Modules, case studies, and simulated scenarios using role-playing, speech, and sharing personal and professional experiences of loss improve psychomotor skills and knowledge. Structured simulated experience can provide skills and knowledge for the nurse's role when providing care of loss (40, 41). Therefore, nursing educators should include the assessment and management of complex grief at all levels of the nursing curriculum and conduct educational research to measure the effectiveness of adding content related to this topic (35).

4. Conclusions

Childhood grief reactions are distinct from those in adults and are affected by developmental and contextual factors such as the age of the child and changes in caregiving environments. Empirically supported interventions can help young people navigate the many grief-related challenges.