1. Background

Childhood development is one of the social determinants of health, on which “child’s play” is an influential factor. Childhood development refers to strategies which provide children’s primary needs from birth until nine years old. These strategies underpin the integrated nature of service provision between government and civil society (families, communities, nongovernmental organizations, and private sector) on one hand and between different sections of government (education, welfare, health, and other sections) on the other (1). Play has positive physical effects on children’s cardiovascular fitness, prevention of obesity and diabetes, and strengthening musculoskeletal system. It also develops brain, in a way which improves linguistic and cognitive abilities, and enhances creative self-expression in arts and imaginary plays. Given the social dimension, it reinforces communication skills, gender and social role development, and makes children independent and assesses their behaviors and abilities (2, 3).

Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child mentions that states should recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts. They also should respect and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational, and leisure activities. According to the article, three roles of protection, provision, and participation can be assumed for states (4).

The population of Iranian children (0 - 10 years old) is 12 million according to the latest census (5). When compared to 2006 census, this indicates a second wave of population growth in the last years; population policies approved by SCRC in 2012 will make this population increase faster than ever (6).

The committee for children’s play is one of the committees formed to develop the policy for children’s health in Iran. Play is effective in childhood learning and development and it is essential that decision makers and planners for society analyze this feature and design national and regional interventions accordingly.

2. Objectives

This study is an effort to identify difficulties and challenges of Iranian children’s play by utilizing the views of stakeholders and national studies.

2.1. Defining Play

Moein Persian dictionary defines play as amusement with something, entertainment, recreation, sports, and deception (7). Play has special definitions in psychology; The Iranian glossary of behavioral sciences defines child’s play as “free activities among children for enjoyment and entertainment” and “direct or indirect activities children do according to their growth and behavior development” (8). It is also defined in the book, The Psychology of Play, as “any purposeful mental or physical activity performed either individually or group-wise in leisure time or at work for enjoyment, relaxation, and satisfaction of real-time or long term needs” (9).

Zimmerman and Salen define play as an activity with properties such as being free, separate (defined within time and space limits), uncertain (its course and results cannot be determined beforehand, and some events are left to the player’s creativity), unproductive (it creates neither good nor wealth), rule-governed, and make-believe (10). Millar considers play not as a set of activities but a set of states and conditions under which some actions are performed (11).

2.2. Comparing Traditional and Contemporary Views

Scientists have long been dealing with children’s activities especially their plays and have proposed various theories some of which are discussed now. First theories of play emerged in the late 19th century and early 20th century and stressed the biological-genetic importance of play. They described play as an innate mechanism which either leads to child’s physical growth or reflects the history of human evolution. Groos explains play as an activity in terms of the children’s surplus energy which they cannot direct towards adaptive actions (12). Verenikina attributes refreshment and rest to play (13). Groos’s pre-exercise theory refers to play as a pre-exercise of child’s behavior in adulthood (14).

Today, none of the theories of play with foundations in human instinct or biological adaptation are supported by psychologists (15). Most of recent theories stress the psychological value of play and its importance in child’s emotional, intellectual, and social development. Freud thinks of play as a means of satisfaction, and considers it necessary in order to keep balance between id (directed by the pleasure principle) and ego (directed by the reality principle) (16). Erikson considers play as a treatment, and believes that by expressing his or her thoughts and needs through play, the child helps the curer reduce the conflicts (17). Piaget looks at play as a means of internalization and consolidation of child’s cognitive development stages (18).

2.3. Review of Literature

Since play is important as the child’s occupation (19) and its being native is a necessity, it is important to consider local studies and relevant policies. Research has revealed the effects of violence on physical and mental illnesses (20). Researchers have shown that many new plays and toys induce aggressive imaginations, violent behaviors, and the choice of pugnacity as a solution, and increase crimes (21). Fischer et al. discovered a positive relationship between violent video games and violent crimes (22). This study warns that children’s game planners and designers should consider educations about toleration and anti-violent values.

According to studies performed on European homes, the two most important factors of cognitive development during infancy are the availability of appropriate play materials and the quality of mother’s involvement with the child (2). Availability of play materials is closely related to the child’s intelligence until 3 years old and children who have been provided with a variety of toys (regardless of gender, race, and social class) have attained more educational achievements (23). Children’s first stage towards the establishment of a sense of self emerges with their attachment to soft toys and cloth (24).

Parents while trying to make them laugh are the first playmates of children. During their growth, children make enduring friendly bonds with their playmates, particularly their parents (2). Pretended plays between mother and 8 - 17 month old toddler affect the child’s intelligence when he or she is five (25). During the early years, parents play vital roles in influencing children’s play and developing their social and communicative skills (26).

A child who suffers limitations or deficiencies in his or her abilities (due to disorders) in performing a normal activity is referred to as the child with special needs (27). In order to evaluate available facilities and propose services to remove defects, it is necessary to analyze data about this group of children and to consult decision makers in funding, and to modify the process of service specialization for these children (27).

Goldstein examines the effects of play in terms of four dimensions: physical effects (muscle strength, weight loss, fine sleep, and reasonable nutrition), psychological effects (problem solving skills, self-confidence, and thinking enrichment), social effects (interpersonal communication skills, society and grouping, negotiation skills, respecting people’s rights, sharing and participation, and forming bonds with parents), and better understanding of art, music, mathematics, and science (2). In general, children’s play is regarded as their occupation and if children are provided and secured with such occupation, they will enjoy physical, mental, and social health.

2.4. Conceptual Framework

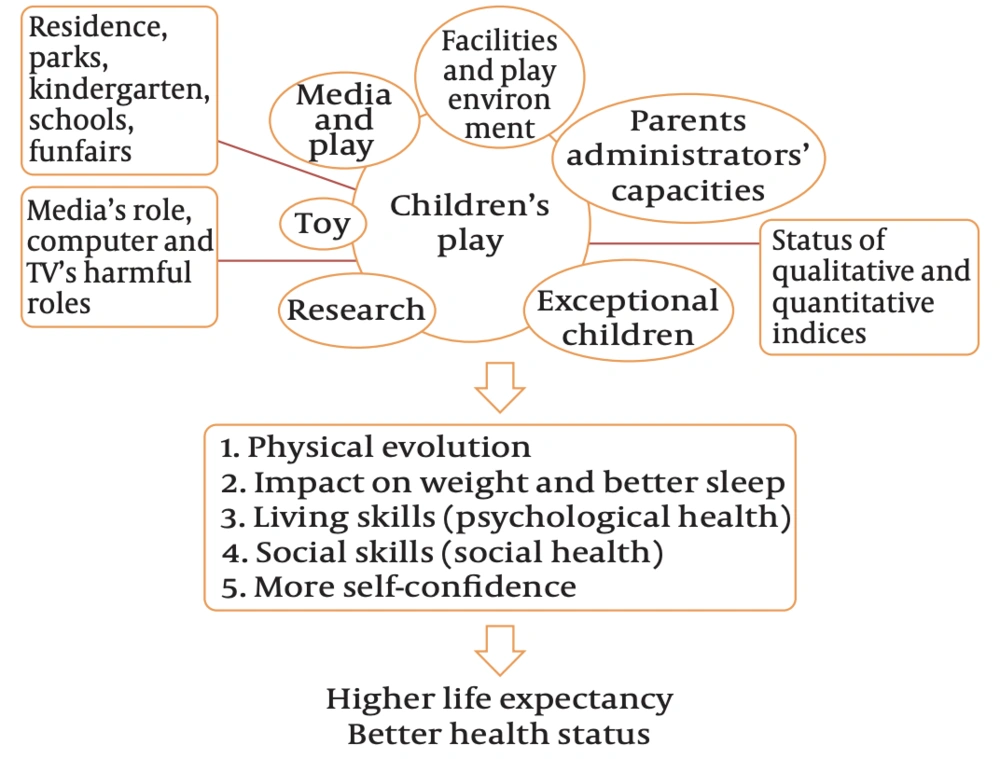

The “child’s play and health effects” conceptual model emerged by reviewing the literature (Figure 1). The model indicates that six domains and subdomains should be referred to by planners of children’s play policies:

Facilities and play environment: residence status, parks, kindergartens, schools, and funfairs;

Capacity building in parents and administrators;

Toy: fitting culture, traditional games, monitoring imports and production, and safety and sanitary standards;

Media and play: quality and quantity of media programs, useful computer games, and benefits to children and parents;

Research and statistics: monitoring the play status in society by means of statistics and related information, and relevant research;

Exceptional children and vulnerable families: creating facilities and capacities for vulnerable families, reducing inequalities, and establishing play in exceptional children’s lives.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Sampling and Recruitment

The model was implemented and stakeholders, natural persons, and responsible organizations directly involved with child’s play were determined and a committee of each stakeholder’s representative was formed (Box 1). Four people were selected from each group of stakeholders, 16 in total, for interview. Deputy for research and education of Tehran parks and green space organization, counselor for education and research department, director of education and publications, director of department for research in ministry of education, director of planning department, the expert in the office of environmental and workplace health, institute for the intellectual development of children-the center for constructive hobbies, director of the center for constructive hobbies-institute for the intellectual development of children, ministry of industries deputy assistant for monitoring and evaluation, welfare organization, the office of children’s affairs, the expert of toy standards form standards institute, head of plastic and nylon guild, council secretariat for toy monitoring, secretary of council for toy monitoring, head of the association for the defense of children’s rights in Iran participated. Therefore a heterogeneous sample (in terms of education, gender, and age) of stakeholders and experts in different fields of children’s play was obtained. Finally, 13 were interviewed (30 - 39 years old, n = 3 - 40 - 49 years old, n = 5 - 50 - 59 years old, n = 4 - above 60 years old, n = 1). The majority of interviewees had an associate degree or a higher degree. After the final interview, it revealed that no new theme was emerging and data saturation was decided.

| Spaces (Schools and Kindergarten) |

| 1. Wellfare organization |

| 2. Ministry of education |

| Media |

| 1. Institute for the intellectual development of children |

| 2. Society of children’s book writers |

| 3. Managing director of a kid’s magazine |

| 4. IRIB children production manager |

| Facility Builders |

| 1. Parks and green space organization |

| 2. Ministry of commerce (import monitoring policies, production license) |

| 3. Ministry of industry and mining (toy production license) |

| 4. Toy retailing association (director/retailers) |

| 5. Toy manufacturer |

| Promoters |

| 1. Association for children’s rights |

| 2. Other related associations |

| 3. Kindergarten teacher training center |

3.2. Design

The semi-structured deep interview was selected for data collection. Interviews were recorded and then transcribed.

3.3. Interview Program

Prior to interviews, official correspondence was carried out and appointments were made. To increase accuracy and comprehensiveness, and also to strengthen the rigor of the study and adhere to ethical principle of confidentiality of the data, reports and interviews and their transcription were carried out by a questioner (M.K). M.K. is a public health professional with a 5 year experience in interviews for qualitative studies. Regarding the conceptual model, research questions were asked in order to obtain information about the facilities and play environment, capacity building in parents and administrators, toys, media, research and statistics, and exceptional children and vulnerable families, and suggested solutions were extracted accordingly (Box 2).

| 1. In your opinion, what are 3 major problems for improving children’s play indices in Iran? (indices trusteeship and monitoring, media, public culture, public facilities) |

| 2. What are your sources of evidence? (statistics, research, international standards, etc.) |

| 3. What are your solutions? |

| 4. What sort of research, evaluation indices or programs can you introduce? |

| 5. How do you evaluate the role of media? |

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Eligible participants were initially approached by the section secretary and given an information sheet. Participants were advised of their right to confidentiality and anonymity and to withdraw at any time.

3.5. Data Analysis

A “denaturalized” approach was adopted for transcription, where idiosyncratic elements of pauses and nonverbal cues were removed (28). Data analysis was conducted according to the steps described by Corbin (29). Firstly in open coding, each line of text was examined and codes were attributed to individual words or sentences to categorize the data according to their meaning and actions. The code would often directly arise from the data, known as an in vivo code (30). Emerging codes were compared with existing codes using constant comparative analysis, to examine similarities or differences. Descriptions were given to codes to ensure reliability in the coding strategy and assist the audit trail. As data analysis progressed, relationships between categories were developed through axial coding (29). Constant comparative analysis and theoretical sampling continued until each category was saturated and no new properties emerged (29).

The texts transcribed by M.K. were read several times and important points mentioned by interviewees were highlighted and suggestions for each point were given at the right edge of the text.

The transcribed texts were read and coded by two of the researchers (M.K. and F.H.) and then put in different categories. After sharing the codes, the coded categories and subjects were discussed, conflicts were eliminated and agreements were achieved.

3.6. Rigor

Koch and Harrington believe that the general process of studies is flexible and evaluation criteria may be produced within the study through text details (31). Strategies employed to increase rigor were: carrying out all the interviews and transcriptions by one questioner (M.K.), monitoring by an experienced researcher in qualitative studies (B.D.), extensive review of references (F.H.); the questioner (M.K.) had no state responsibility in the field of children’s play; notes and codes were returned to the interviewees to eliminate possible contradictions. Interviewees’ own words were utilized for data analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Society’s Little Knowledge of “Children’s Plays”

In the case of capacity building in parents and administrators, items such as society’s little knowledge about the importance of play, have led to inattention of organizations such as ministry of education to play, and insufficient energy and money spent on play by parents and administrators.

“People generally consider aesthetic and recreational aspects of toys, while toys hygiene is especially important for children and since they may use toys unreasonably, they may put them in their mouth for example, or they have skin contact with toys this issue must be taken into account.” Interviewee no. 5.

“Majority of people pay more attention to children’s food and clothing (first levels of Maslow’s pyramid) than their education and play.” Interviewee no. 6.

“Lack of belief in the fact that play is important and necessary for children anytime and anywhere. For example foreign planes give children free toys to play with during flights.” Interviewee no. 10.

“Our biggest problem is with public culture; people and authorities’ unfamiliarity with the impacts of plays and toys on children’s physical, psychological, and personality health. They trivialize plays and toys in a way that Dehkhoda Dictionary defines play as “a futile activity”.” Interviewee no. 11.

4.2. Absence of Administrators for Children’s Play

In the case research and statistics, issues such as lack of opinion poll and accurate statistics about the risks and harms of plays and toys, lack of indices for children’s play policy, negligence in setting research priorities for children’s play are among the related problems.

“Absence of a well-researched program in the field of children and production of commercial programs instead (maybe 30 to 40 percent of children’s programs are researched and the rest are merely for entertainment).” Interview no. 7.

“Basically, the process of importing plays and toys is not well-researched. Many toys which are banned in exporter countries are sold in our markets and shops.” Interview no. 11. Shortage of public facilities for children’s play and improper geographical and demographic availability.

In the realm of facilities and play environment particularly in metropolises, shrinkage of schools, play environments, and residential areas especially apartments, disproportion between play environments and park areas, decreasing children’s group games in the society due to one-child tendencies, shortage of play facilities in nurseries of workplaces are the obstacles to promote children’s play. Insecurity of parks due to presence of hooligans, drug use, and disproportion between restaurants and water-fountains hygiene, and ergonomics of parks and children’s age are yet other obstacles to use such facilities. Outdated nonstandard play materials in parks for different age groups, lack of play materials for mental strengthening and creativity of children and absence of zoos reduce the attractiveness of parks for children. At macro-level policies, refusal to get ideas and inspirations from leading countries in children’s play, apparent inequality in distribution of play materials, general shortage of play facilities and availability are the obstacles to promote children’s play both qualitatively and quantitatively. Inattention of parents and related organizations to exceptional children's needs, shortage of play materials in disadvantaged parts of the country and cities’ marginal areas, wrong beliefs of vulnerable families in prioritizing issues other than children’s play are the obstacles to promote children’s play for exceptional children and vulnerable families.

“Play materials are not varied enough. Users of such materials are also of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds and do not use a homogeneous set of these materials.” Interview no. 1. “Limitations in children’s play space or even in their living space are really troublesome.” Interview no. 8.

4.3. Absence of Policies for Iranian “Toy”

In the realm of toys, the macro-level problems are poor supervision of imported toys by the ministry of health despite the regulations already existing, 50-fold increase in imports (especially of poor quality toys for profitability) in the last 8 years, absence of monitoring domestic toys by institute of standards (it monitors imports), inattention to cultural considerations such as incongruity of toys and various ethnic cultures, no revival of traditional lively games which are replaced by stagnant computer games; these are risks for children’s play health. On the other hand, parents’ little awareness of toys quality and types appropriate to children’s age, and that expensive imported or domestic toys will have adverse effects on the play status. “But authorities may not pay attention to and prioritize toys hygiene because of unknown health-related consequences of unhygienic toys.” Interview no. 5.

4.4. Media’s Little Actions in Relation to “Play”

In terms of media, there also exist difficulties for children’ play such as poor educational programs for teaching play to children and its importance to parents, shortage of kids’ magazines, and harmful computer games.

“Given the limitations of children’s living space (apartments) or kindergartens, they mostly spend their time watching TV; this is very important because TV programs significantly affect children.” Interview no. 12.

The most important promotion interventions in stakeholders’ opinion are redefinition and revival of traditional games of different ethnicities, utilization of media to promote public culture, and designing social marketing plans to increase public awareness about children’s play. Several compulsory interventions are also suggested which include creation of a labeling system and establishing toy standards, revision of residential construction by laws and regulations to include children’s play facilities, revision of curriculums as plays in education, the ministry of health’s redefinition of monitoring imported toys, compilation of an annual report for supreme council of health and food security, changing the statute of the council for toy monitoring to “national council for Iranian children’s play” approved by the Cabinet or SCRC. For facilitative interventions, the following are suggested: research on problems of toy manufacturing in Iran, setting policies for developing and supporting domestic productions, defining play indices and its basic measures, developing a comprehensive plan for children’s play until 2025, and training merchants about children’s plays and games.

5. Discussion

People and administrators’ little or average knowledge of “children’s plays”, absence of administrators for policy making, planning and generating statistics and evidence base for children’s play, shortage of public facilities for children’s play and improper geographical and demographic availability (within cities, between cities and villages), absence of policies for Iranian “toy” (including poor quality imports, domestic products, safety and hygiene), and little attention of media to “play” are the five major problems found in the present study. As for promotion intervention, actions to increase society’s awareness such as using media and social marketing approach in developing program are suggested. With regards to compulsory interventions, utilization of municipalities’ capacities to improve residential and recreational areas, of the ministry of health’s to monitor toys imports, and of Institute of Standard’s to establish toys standards are essential. As to facilitative interventions, research and policy making, enhancement of monitoring system for related indices, and training courses for various social groups are recommended.

In this study views of parents, kindergarten and preschool teachers, teachers of children with special needs, and social workers helping vulnerable families were not surveyed and it is necessary to investigate the needs of these groups in another research.

Mohtashami et al. examined 33 most played games among children of Tehran and found that dynamic and group games such as zou (kabaddi), ganieh (a different version of hopscotch), and stop-machine are the most wanted and played games; this necessitates enough vast spaces for children’s play (32). In studies titled “achieving open space design principles for children’s play in residential areas” and “designing children’s play space” Razjouian and Paknejad respectively proposed methods for design and construction of open spaces in residential areas and mentioned the necessity of children’s access to leisure spaces (33, 34). Saremi examined three important issues, namely a description or monograph of funfair, visitors, and the impacts in his study “a sociological examination of funfair and its impacts on children’s socialization process” and referred to the need for recreational spaces for children’s play (35). Faraji investigated the effects of computer game thrills on children’s mental activities and safety indices and stressed the role media play in causing or preventing violence (36). The same researchers also found that computer games are now the most interesting entertainment among children and adolescents (21). Iranian researchers believe that the most influential factor for bestselling toys are visual attractiveness, cheapness, and packaging; therefore, mention culture building and informing parents and toy manufacturers as the most important actions in the field of children’s play (37). In Ireland’s national play policy for children, first the current state of affairs was explained, then, challenges and solutions were investigated on the basis of Article 31 of the United Nations convention on the rights of the child, challenges, the next step was to implement and monitor the strategies and finally a performance map was presented (38). Compared to this document, findings of the present study show that methods for developing and compiling goals and interventions vary, but since there is no statistics about Iranian children’s play, goal setting and evaluation are subject to errors. It is therefore necessary to carry out national research in order to design and establish monitoring system for children’s play indices and their relationship with improvement of physical, psychological, and social indices. This requires commitment at national level by administrators and the State which in turn necessitates capacity building in administrators for children’s play.

The conceptual model proposed here may be used by planners and policy makers to gain support for “children and play” policy and to define monitoring indices, set goals at strategic levels and final impact. Analysis of children’s play status in a smaller population is also possible in the same way.

Sending a report of this study to stakeholders is the first step to implement the results. Initiation and approval by supreme council of health and food security would help the legitimation of this program; developing the statute of national council for children’s play is also a necessary step to implement projects of the program.