1. Background

Cow milk protein allergy (CMPA), an immunological reaction to cow milk protein, is the most common food allergy in early childhood (1, 2). Approximately 2% - 3% of infants or young children suffer from CMPA with different symptoms, such as urticaria, angio-edema, vomiting, diarrhea, and anaphylactoid purpura (3, 4). Generally, 80% - 90% of CMPA patients can acquire tolerance to cow milk protein by 5 years of age with long-term treatment (5). However, recent reports have shown that the age of CMPA patients often extends past 5 years, and in these cases CMPA is often accompanied by aggravated symptoms (6, 7).

Current views assert that allergic diseases are associated with the reduction of microbial exposure and alteration of microbial communities (8-10). Differences in gut microbial composition between allergic and healthy infants have also been reported (11-13). Fewer Bifidobacterium and more Clostridium were observed in the gut microbiota of allergic children than in those of healthy children, and Bifidobacterium pseudocatenulatum was reported to be associated with atopic eczema in a nested case-control study on the fecal microbiota of infants (8, 10, 11). Similarly, Thompson-Chagoyan et al. (4) found a significantly higher degree of biodiversity in the feces of CMPA infants than in that of healthy infants, and they found that both Clostridium coccoides and Atopobium groups were more prevalent in the feces of CMPA infants than in the feces of healthy infants. However, with the increasing age of onset for CMPA, a further study of fecal microbiota in older children seems to be crucial.

Polymerase chain reaction-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (PCR-DGGE) is commonly used to analyze bacterial diversity and microbial communities in feces, and the use of this technique allows for the identification of uncultivated microorganisms by traditional culture-based methods (14). In previous studies, PCR-DGGE combined with gene sequencing technology has been used to reveal the fecal microbiota characteristics of some diseases, including atopic eczema, irritable bowel disease, celiac disease, and rotavirus diarrhea (11, 15-17).

In this study, fecal samples were collected from 12 CMPA children and 12 healthy children. The age range of the volunteers was 5 - 8 years. We compared the biodiversity of fecal microbiota in children with CMPA to that of healthy children, and we analyzed the differences in the prevalences of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and C. coccoides within these two groups using PCR-DGGE and gene sequencing technology.

2. Objectives

Twenty-four fecal samples were prepared over a 12-month period (May, 2012 to October, 2013), during which 12 fecal samples were collected from children with CMPA (mean age 6.4 years; range 5 - 8 years; sex ratio 1: 1), who suffered from abdominal distention, diarrhea, eczema, and allergic purpura. CMPA was diagnosed by three tests: a skin prick test, analysis of serum samples, and a double-blind placebo controlled cow’s milk challenge in the Harbin children s hospital (Heilongjiang, China) (18). In addition, 12 healthy age- and sex-matched subjects were selected from volunteers in Harbin city. In addition, the healthy children had no history of CMPA or any other allergies. Neither children with CMPA nor healthy controls in this study had taken antibiotics for a period of at least 4 weeks. All children were born normally, had been breastfed as infants, and had healthy parents with no history of illness. This study was performed with the approval of the local ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from the children’s parents.

3. Methods

3.1. Feces Sampling

All feces samples were collected into sterile plastic tubes, immediately transferred to the lab, and stored at -80°C until analysis.

3.2. Total DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

Approximately 200 mg (wet weight) feces samples were thawed at room temperature and weighed in order to extract total DNA (15). The total DNA was extracted with a QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, and total DNA was amplified with v3 of universal primers, as well as Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and C. coccoides primers (19-22). The primers and PCR amplifirotocols were performed according to previously reported procedures. PCR amplification was estimated by electrophoresis in a 1.0 agarose gel (wt/vol) after staining with ethidium bromide.

3.3. Analysis of Fecal Microbiota by DGGE

The DGGE scheme of PCR amplification products was performed using the DCode Universal Mutation Detection System (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA, USA) with an 8 in 1 × TAE running buffer. The stock solutions were a 100 denaturing solution containing 7.0 M of urea and 40 (vol/vol) of formamide, as well as a polyacrylamide solution containing no denaturing components; the desired denaturing gradient was obtained according to percentages. The electrophoresis was performed at 20 v for 10 minutes, 70 v for 18 hours for the universal bacterial primer, 85 v for 16 hours for Bifidobacterium, 70 v for 16 hours for Lactobacillus, and 85 v for 16 hours for C. coccoides at a constant temperature of 60°C (19-22). After electrophoresis, the DGGE gels were stained for 30 minutes in a GeneFinder (0.5 μg/mL) and photographed under UV transillumination.

3.4. Sequence Analysis of DGGE Bands

Bands of interest were excised directly from the gels with a sterile blade, soaked in 50 μL of TE buffer, and incubated overnight at 4°C. The DNA was reamplified with the previous primers without the GC-clamp. The PCR products were then sent to the Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI) for sequencing. The identity of the sequences was determined by the BLAST program in the GenBank database, which is available online at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The biodiversity of fecal microbiota was evaluated according to the number of bands and the Shannon-Weaver index of biodiversity (H′) in accordance with previous studies (16, 23). Similarities analysis was conducted using the unweighted-pair group method with the arithmetic average (UPGMA) clustering algorithm in Quantity One software (24). All data analyses were performed using the statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) software v.20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

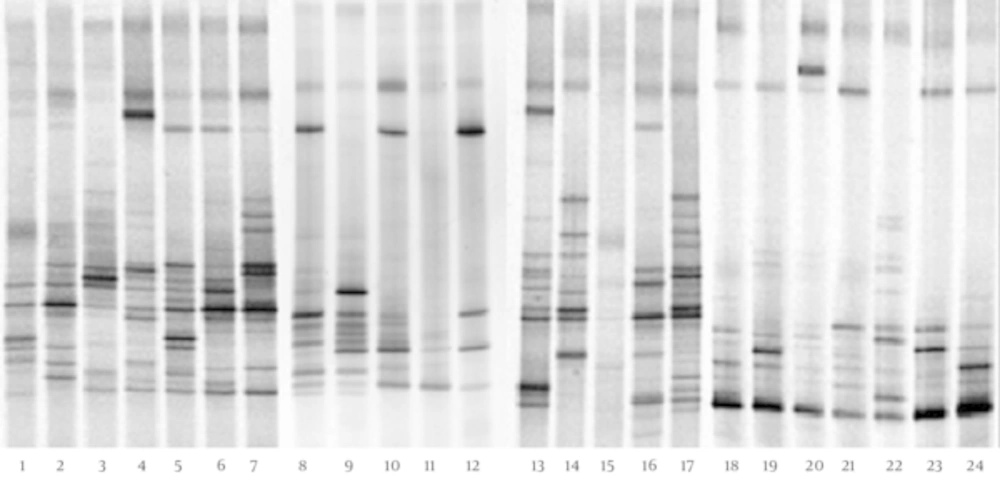

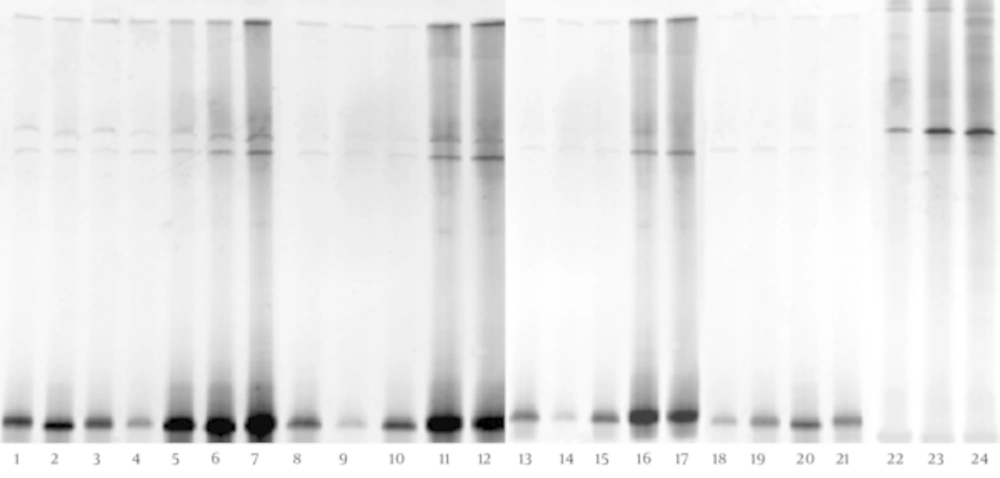

The DGGE fingerprints of dominant fecal microbiota from all 24 stool samples taken from 12 children with CMPA and 12 healthy controls were shown by applying PCR-DGGE technology (Figure 1). The mean number of bands, mean Shannon-Weaver index, and microbiotic characteristics of the two groups were revealed and compared; the details are shown in Table 1. The results show that the mean number of bands and the mean Shannon-Weaver index of children with CMPA were significantly higher than those of healthy controls (P < 0.05), which indicates a significantly greater degree of diversity in the fecal microbiota of children with CMPA than in that of healthy children.

| Group | Dominant Fecal Microbiota | Lactobacillus | Bifidobacterium | C. coccoides | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DGGE Bandsb | Shannon-Weaver | Intragroupc (H′/ H Max ′) | DGGE Bands | Shannon-Weaver | DGGE Bands | Shannon-Weaver | DGGE Bands | Shannon-Weaver | |

| CMPA | 14.17 ± 1.03d | 2.58 ± 0.08d | 53.41 ± 8.58d | 4.88 ± 0.15d | 1.57 ± 0.05d | 4.25 ± 1.29d | 1.21 ± 0.31d | 3.89 ± 0.24d | 1.24 ± 0.11d |

| HC | 9.75 ± 2.59e | 2.15 ± 0.28e | 41.00 ± 16.32e | 5.04 ± 0.07d | 1.55 ± 0.09d | 7.50 ± 1.38e | 1.65 ± 0.30e | 2.89 ± 0.31e | 1.00 ± 0.03e |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD.

bDifferent (P < Number of DGGE bands produced by each sample).

cDice similarity coefficients comparing DGGE band profiles within individuals of each group.

dColumn values with the different letters were significant at 0.05.

eThe P value for each comparison is shown on each column.

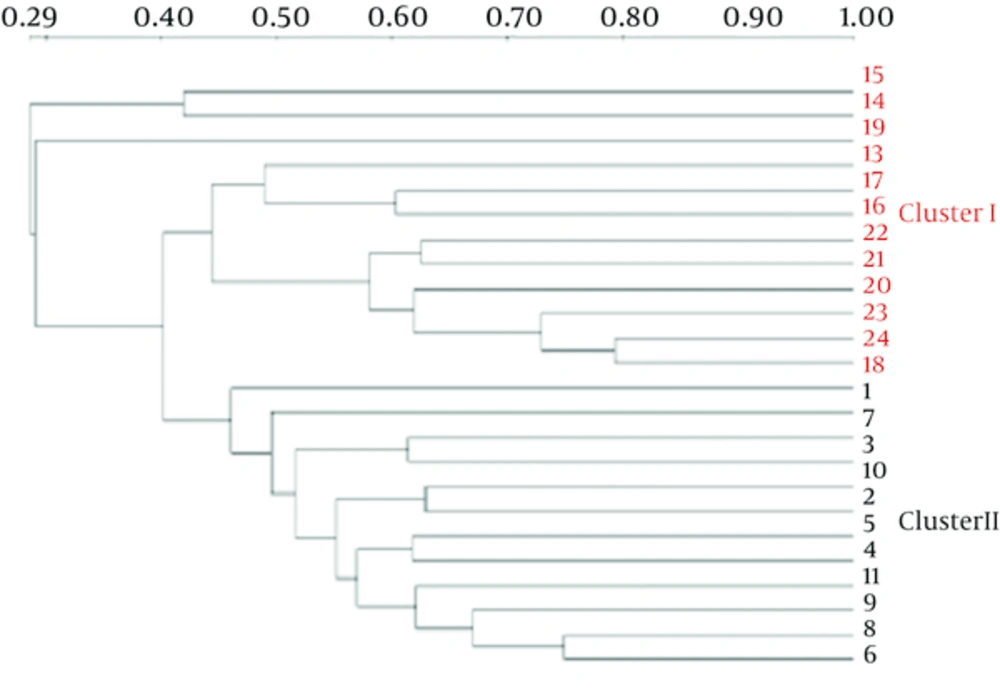

The Dice similarity coefficients (Table 1) and UPGMA dendrograms (Figure 2) based on the fecal microbiota of CMPA children and healthy children were carried out using Quantity One software. The results show that the index of similarity coefficient ranged from 32.3 - 74.8 in the CMPA group and from 21 - 77.1 in the healthy controls. The microbiota similarity values of the two groups were 53.41 ± 8.58 and 41.00 ± 16.32, respectively (Table 1), which indicates that the intragroup similarities in children with CMPA were greater than those in healthy controls. According to the UPGMA results of the DGGE images (Figure 2), the fecal microbiota of children with CMPA were clustered together, unlike the fecal microbiota of healthy controls.

The dominant bands were selected from DGGE profiles for sequencing. The sequence results were submitted to the GenBank database for relative identification by BLAST. The results (Appendix 1 in the Supplementary File) show that Bacteroides fragilis, B. helcogenes, Bacteroides sp., Escherichia coli, Erysipelotrichaceae, B. faecichinchillae, Clostridium sp., uncultured Coprobacillus sp., uncultured Ruminococcaceae, uncultured Bacteroides, and uncultured bacterium were found in the dominant bacterial community in the fecal microbiota of both children with CMPA and healthy children. All dominant bacteria in feces belonged to Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria. However, Bacteroides, Clostridium, and Escherichia coli were more abundant in the feces of children with CMPA than in the feces of healthy children.

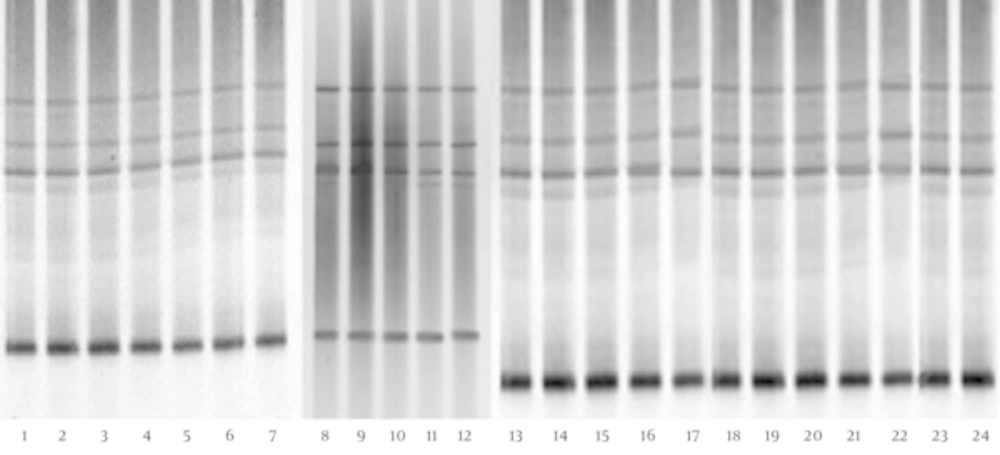

The DGGE fingerprints of Lactobacillus species-specific PCR products of children with CMPA and healthy controls are shown in Figure 3. The results show no significant difference between the biodiversity of the Lactobacillus group in the fecal microbiota of children with CMPA and that of healthy controls (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Furthermore, the sequencing data (Table 2) reveal that L. crispatus, L. brevis, L. plantarum, L. acidophilus, and L. fermentum were detected in the feces of children with CMPA and healthy controls; however, L. fermentum was more prevalent in the fecal microbiota of 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA than in healthy children.

| Band No. | Closest Relative (Accession Number) | Identities (%) | CMPA n = 12 (%) | HC n = 12 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus | ||||

| 4 - 1, 24 - 1 | L. crispatus (AJ242969) | 99 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) |

| 4 - 2, 24 - 2 | L. brevis (JQ436725) | 98 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) |

| 4 - 3, 24 - 3 | L. plantarum (KF682392) | 98 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) |

| 4 - 4, 24 - 4 | L. acidophilus (JQ031741) | 99 | 9 (75) | 12 (100) |

| 4 - 5, 24 - 5 | L. fermentum (KC145829) | 97 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) |

| Bifidobacterium | ||||

| 1 - 1, 6 - 1, 19 - 1 | B. breve (AY172657) | 99 | 9 (75) | 9 (75) |

| 1 - 2, 6 - 2, 19 - 2 | B. longum (GU723326) | 98 | 11 (91.7) | 12 (100) |

| 13 - 2, 19 - 3 | B. bifidum (AJ311604) | 97 | 0 (0) | 7 (58.3) |

| 1 - 5, 6 - 3, 19 - 6 | B.adolescentis (AB125906) | 99 | 7 (58.3) | 8 (66.7) |

| 3 - 5, 19 - 8, 16 - 8 | B. catenulatum (AB846175) | 99 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) |

| C. coccoides | ||||

| 1 - 1 | C. hathewayi (NR036928) | 97 | 12 (100) | 12 (100) |

| 1 - 2 | C. celerecrescens (JN650298) | 98 | 12 (100) | 0 (0) |

| 1 - 3, 22 - 2 | C. saccharolyticum (FJ957875) | 98 | 12 (100) | 11 (91.6) |

| 1 - 4 | Uncultured Clostridium sp. (JQ713920) | 98 | 12 (100) | 9 (75) |

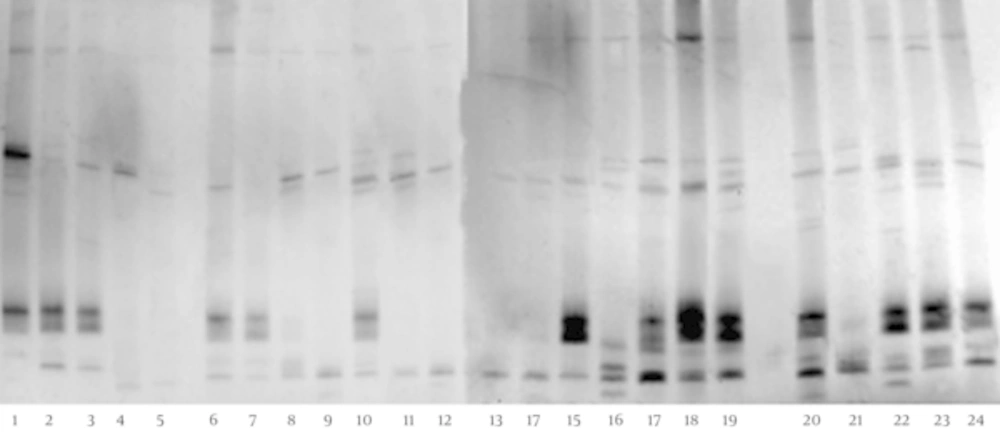

The DGGE fingerprints of Bifidobacterium (Figure 4) indicate that these fecal microbiota of children with CMPA showed a significantly lower level (P < 0.05) of biodiversity than the fecal microbiota of healthy individuals (Table 1). Five different bands were identified with gene sequencing, the details of which (Table 2) show significant reductions in B. adolescentis, B. longum, B. catenulatum, and B. breve in the fecal microbiota of children with CMPA. Furthermore, B. bifidum was found only in the feces of healthy children.

The DGGE fingerprints of the C. coccoides PCR products of children with CMPA and healthy controls are shown in Figure 5. The images show that these fecal microbiota of children with CMPA have a significantly higher degree (P < 0.05) of diversity than the fecal microbiota of healthy individuals (Table 1). The sequencing results (Table 2) indicate that C. hathewayi, C. saccharolyticum, and uncultured Clostridium sp. were present in all stool samples. Interestingly, C. celerecrescens was present in all feces samples of children with CMPA, but it was not found in the feces of healthy controls.

5. Discussion

Gut microbiota are considered part of the genetic phenotype of humans, and they have a close relationship with the host’s health (22). The complex intestinal microbial flora harbored by individuals have long been proposed to contribute to intestinal health and disease, and intestinal microbiota are increasingly considered symbiotic partners in the maintenance of human health (25). Many diseases are reportedly associated with gut microbiota imbalance, and a balanced intestinal microenvironment is beneficial to human well-being (26, 27).

CMPA is a common allergy in children, and it is closely related to prominent changes in gut microbiota (13). The fecal microbiota characteristics of children with CMPA < 5 years old has been determined; (28) however, studies on the biodiversity of fecal microbiota in children with CMPA > 5 five years old are limited. Importantly, CMPA becomes serious when it affects older children (6, 7). In the current study, the main observations were that the diversity of the fecal microbiota in CMPA children in the range of 5–8-years-old was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of healthy individuals in the same age range, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies in infants and children <5 years old (29, 30). In addition, higher levels of Clostridium and Escherichia coli, which have been proven to play important roles in more severe manifestations of allergies along with specific IgE antibodies to food, diarrhea, and inflammatory processes (17, 31, 32) were present in the DGGE gels of children with CMPA. Bacteroides sp. is another important genus in feces, and it presented at significantly higher levels in the fecal microbiota of 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA than in healthy children in our study. However, in contrast with our current findings, Thompson-Chagoyan et al. (4) reported no difference between CMPA children and healthy children in terms of the prevalence of the Bacteroides group in the gut flora. The reason for the difference in the results between our study and the previous study may be due to differences in the patients’ ages.

Several important species in fecal microbiota have been shown to be altered in 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA in comparison with healthy children. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have functional anti-inflammatory activity, and they can provoke immune responses by inducing the action of T-cells associated with CMPA (27, 33, 34). Various results of the diversity in the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium groups in the allergy patients have been reported; on the one hand, the prevalence of colonic Bifidobacteria was lower in allergic infants than in healthy infants (10, 28, 35). In addition, Thompson-Chagoyan et al. (4) found no differences between children with CMPA and healthy children in terms of the prevalence of the Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus groups in gut flora. In our study, the diversity of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium were further determined. No significant difference in terms of the diversity of Lactobacillus was identified between 5 - 8-year-old children with and without CMPA; however, the prevalence of L. fermentum in the feces of 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA tended to be lower than in the feces of healthy children. Meanwhile, a significant reduction in the prevalence of Bifidobacterium was discovered in CMPA children. Furthermore, B. adolescentis and B. longum could be considered to play a more important role than other species in genus Bifidobacteria for 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA. In addition, C. coccoides is one of the most predominant groups in the human gut microbiota, and it has been reported to have a close connection with CMPA (22). Previous studies have shown that the feces of infants with CMPA have a significantly higher proportion of the C. coccoides group than those of healthy controls (13, 18, 22). Consistently, the same tendency has been confirmed in 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA in our study. Another study showed that C. celerecrescens was only present in the fecal microbiota of 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA, which suggests that C. celerecrescens may be responsible for the hypersensitive reaction to cow milk protein in this age group.

In previous reports, urticaria, angioedema, erythematous rash, vomiting, diarrhea, bronchospasms, and anaphylactic shock have been reported as symptoms of CMPA (4). In this study, 12 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA all suffered from serious abdominal distention, diarrhea, eczema, and allergic purpura; however, there were no other symptoms in this population, which indicates that the symptoms of CMPA change as patient age increases. This might be another reason why there were differences in the diversity of fecal microbiota among patients with different ages. The specific PCR-DGGE results showed that L. fermentum, B. adolescentis, B. longum, B. catenulatum, and B. bifidum played important roles in their respective genii, which suggests the possibility of prevention and treatment of CMPA using probiotics that support these bacteria.

In conclusion, compared with healthy children, 5 - 8-year-old children with CMPA exhibit higher diversity of dominant microbiota and C. coccoides groups and lower diversity of Bifidobacterium in fecal microbiota. Bacteroides, Clostridium, and Escherichia coli were more prevalent in the fecal microbiota of CMPA children. In addition, C. celerecrescens was only found in the fecal microbiota of CMPA children, whereas B. bifidum was found only in the healthy children. These results provide a possible basis for discovering the relationship between CMPA and intestinal microbiota in 5 - 8-year-old children.