1. Introduction

Lipoblastoma is a rare benign tumor that originates in the embryonal fat (1). More than 90% of patients are diagnosed at under 5 years of age (2), and a male predominance has been reported (1). Although lipoblastoma can arise from various anatomical sites including the extremities, trunk, and neck (1), a few reported cases extended into the spine. Among the reported cases, surgical interventions were performed against neurological deficit. We describe a girl who has developed a lipoblastoma that extended into the cervical spine and she received early surgical intervention.

2. Case Presentation

2.1. History and Examination

A previously healthy 3-year-old girl presented with a cervical tumor. Physical examination revealed a soft tumor located in the left lateral region of her neck, and the tumor was 3 cm in diameter. The tumor has grown in the two weeks after onset; however no neurological deficit was demonstrated and no disturbance in movement of the extremity and deep tendon reflex. Laboratory findings were unremarkable.

2.2. Imaging Findings

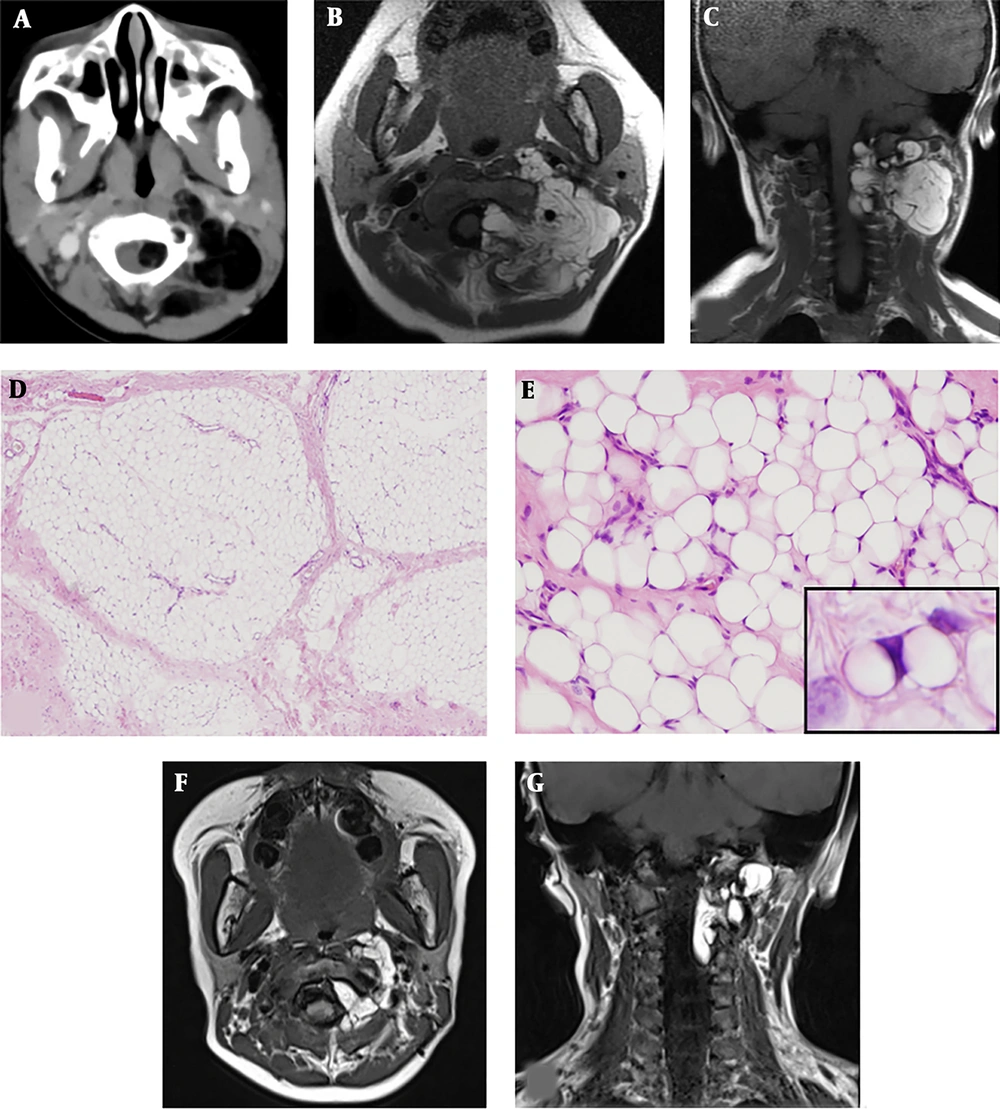

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed an irregular dumbbell-shaped tumor that remarkably extended into the extradural space at the level of C1/C2 (Figure 1A) and compressed the spinal cord at the level of C1 to C3; however, bone destruction was not observed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed hyperintensity of the tumor on T1-weighted images (Figure 1B and 1C) and also hyperintensity on T2-weigheted images (not shown).

A, The upper panels show the imaging at onset. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed an irregularly shaped fatty tumor extending into the extradural space at the level of C1/C2; B,C, Cervical magnetic resonance imaging showed high signal intensity on T1-weighted images; D The middle panels show microscopic examination of resected tissues: The lobules of adipose tissue separated by fibrous septa (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original magnification, × 40); E, The adipose tissue comprised variously sized univacuolated adipocytes with sparse signet-ring or bivacuolated lipoblasts (× 400) (E inset). The adipocytes showed no nuclear atypia (hematoxylin and eosin staining; original magnification, × 200); F, G, The lower panel shows postoperative magnetic resonance imaging: T1-weighted images showed that the extra-spinal tumor had decreased in size.

2.3. Pathological Findings

The incisional biopsy was performed two weeks after onset. The pathological diagnosis obtained by an incisional biopsy of the cervical tumor was lipoblastoma. Microscopic examination showed a lobular architecture of the adipose tissue separated by fibrous septa (Figure 1D). The adipose tissue consisted of sheet-like proliferations of variously sized and unvacuolated adipocytes on a focally myxoid background (Figure 1E). Bivacuolated or signet-ring lipoblasts were sparsely observed (Figure 1E, inset).

Malignant findings were not demonstrated in the resected tumor.

2.4. Operation

After two weeks from diagnosis, the operation was performed by an anterolateral approach for decompression of the spinal cord. The tumor was yellow-white in color, elastic hard, and multi-compartmental. The adhesion of the tumor to the surrounding tissue was remarkably observed, and the C1 and C2 posterior roots were involved in the tumor. First, the tumor outside of the spinal canal was resected. After confirmation of the blood flow in the vertebral artery by Doppler ultrasonography, the tumor was detached from the vertebral artery. The residual extradural tumor inside the spinal canal was partially resected through the dilated C1/C2 preserving the C2 and C3 vertebral arches and the vertebral joint. The partial resection resulted in decompression of the tumor between C1 and C2.

2.5. Postoperative Course

The tumor volume outside of the spine decreased by 90% (Figure 1F, 1G), however the size of the residual tumor in the subdural space was unchanged. Follow-up MRI was continued every 3 to 6 months postoperatively. Despite that the residual tumor in her spinal canal remained unchanged, she developed no neurological symptoms for 58 months postoperatively. We have explained to the parents the perspective that the residual tumor will differentiate into a common lipoma in a few years.

3. Discussion

We experienced a 3-year-old girl with a dumbbell-shaped cervical lipoblastoma that extended into the cervical spine. Extension of a lipoblastoma into the spinal canal is relatively rare (Table 1) (3-12).

| Authors | Patient’s Age, Sex | Primary Lesion, Spinal Lesion | Neurological Symptoms | Surgical Procedure (Spinal Tumor) | Postoperative Neurological Symptoms | Follow-Up Period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Choi and Song | 3 y, M | Pelvis, L4-lower sacrum | Bladder and rectal disturbance | Partial resection | Not available | No progress for 3 months |

| Dogan et al. | 1 y, M | Mediastinum, Th2-3 | Paraparesis | Partial resection | Improved | No recurrence for 6 months |

| Duhaime et al. | 4 y, F | Neck, C3-6 | None | Complete resection | None | No recurrence for 6 months |

| Fleming et al. | 4 y, M | Spine, C7-Th6 | Paraparesis (unspecified) | Partial resection | Improved | Not available |

| Giri et al. | 1 y, M | Spine, Th8-L2 | Paraplegia, bladder and rectal disturbance | Resection (unspecified) | No change | No progress for 6 months |

| Ko et al. | 1 y, M | Mediastinum, C6-Th5 | Paraparesis | Complete resection | Partially improved (right upper extremity weakness due to operation) | Not available |

| O’Brien et al. | 10 mo, F | Neck, C3-7 | Monoparesis, torticollis | Partial resection | Quadriparesis after 5 months and improvement after reoperation | No progress for 120 months |

| O’Donnell et al. | 1 y, M | Mediastinum, Th1-2 | Monoparesis, Horner’s syndrome | Partial resection | No change | No progress for 24 months |

| Raman Sharma et al. | 2 y, F | Mediastinum, Th1-2 | Gait disturbance | Complete resection | Improved | No recurrence for 4 months |

| Sun et al. | 1 y, M | Neck, C4-Th1 | Hemiparesis | Partial resection | Partially improved | No progress for 3 months |

| Present case | 3 y, F | Neck, C1-3 | None | Partial resection | None | No progress for 58 months |

Lipoblastoma is a benign tumor that can be treated by complete surgical excision and has an excellent prognosis despite its potential for local invasion (13). Metastases have never been reported; however, the recurrence rate ranges from 14% to 25% (13). The minor diffuse infiltrative type (i.e., lipoblastomatosis) has a higher recurrence rate because of its infiltrative nature and indistinct borders.

Lipoblastoma extends into the spinal canal infrequently (Table 1). We have reviewed the similar case reports and about 80 percent of reported patients had neurological defects and they were treated by surgical excision of the tumor. However, complete resection was performed in one-third of the patients. The neurological sequelae or progression of residual tumor have been reported in the cases of partial resection, although the follow-up term was short in these previous studies. Based on these preceding cases, we chose to perform prophylactic resection of the tumor, to avoid neurological defect, preserving the bony supporting tissue. Complete removal would have required laminectomy by a posteromedial approach; however, this was associated with the risk of neurological defects, deformity of the spinal column, and dropped head syndrome.

Little is known about the long-term prognosis of intra-spinal lipoblastoma with a residual tumor. As we have shown the review of literature in Table 1, neurological sequelae or recurrence have been reported, and early surgical interventions performed. However, some case reports have described differentiation of the residual tumor into a common lipoma and subsequent spontaneous resolution (5, 8, 10, 14). Therefore, we selected a wait-and-see strategy for the residual tumor. The patient is now doing well more than four-years after the surgery.

In conclusion, we treated a child with a lipoblastoma that extended into the cervical spine. Early surgical intervention and decompression of the tumor was effective to avoid the neurological defects. Surgeons should consider preservation of the bony supporting tissue to avoid sequelae in patients with a dumbbell-shaped lipoblastoma that has invaded the vertebral canal.

Portions of this work were presented in poster form at the 118th Annual Meeting of the Japan Pediatric Society (Osaka).