Dear Editor,

The Journal recently published a study (1) on the current data concerning exposure to second hand smoking among Iranian children and adolescents. In particular, the authors noted low parental education correlating with increased tobacco smoke exposure (TSE) frequency among children and pointed out a need to improve the effectiveness of family-centered counseling as well as legislation for smoke free home.

Passive smoking is consequently demonstrated to be causally associated with a large number of human diseases although in the view of many authors the obvious association between parental smoking and recurrent respiratory infections or asthma seems to be ignored by many pediatricians and general practitioners (2). Nevertheless, vast majority of parents (89%) claim that asking about parental smoking status is an important part of pediatrician’s role (3).

In our recent analysis, 77% (392 out of 506) of parents whose children hospitalized due to respiratory problems have never been asked about smoking habits during routine pediatric consultation (data in preparation). Interestingly, this tendency significantly reduced among those whose health care service was performed by GPs (59%). A strong discrepancy between different cultures/nations seems to exist since the proportion of pediatricians who routinely do not ask about environmental tobacco smoke in the US and Israel was 27% and 43%, respectively (4, 5). However, these data still indicate relatively low rates of screening and counseling for parental smoking in pediatric practices while regrettably, among these families many parents (40%) report regular smoking habits.

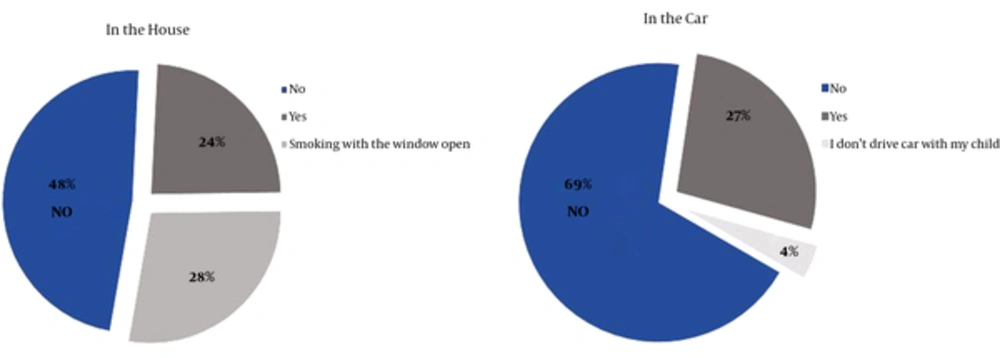

As reported by our investigation, rule banning smoking in the car, in which a child travels, is valid for only 23% of Polish families. This value is surprisingly low compared to other countries (data in preparation). In Australia, up to 96% of respondents claim that they prohibit smoking in the car (6). In Wales, only 9% of the respondents agree for smoking inside the vehicle which is used by the child (7). It is therefore crucial that pediatricians and general practitioners suggest quitting smoking in vehicles used by children.

According to our survey, smoking parents try to quit smoking to improve their child’s health and such attempts were reported by 4 out of 10 smoking parents.

We do agree with Kelishadi and colleagues that the current public health education methods of anti-smoking interventions are inadequate maybe due to the lack of attractive smoking cessation tools. E-cigarettes seem to be an interesting alternative due to tremendous public interest and current data suggesting that even though they are not completely neutral for human health, they still are less harmful to children than conventional cigarettes (8).