1. Context

Depression is one of the most common psychiatric disorders (1). According to the global burden of disease (2017), globally, more than 264 million people suffer from depression. Besides, it is estimated that it accounts for about 44,000,000 years lived with disability (YLDs). According to this study, compared to 2007, the YLD of depression has increased by 14.3% (2). Everyone is at risk of depression, but some are more vulnerable because of a variety of factors ranging from living conditions to genetic factors (3). Particular risk factors for depression include stressful life events (4), genetics (5), adverse childhood incidents (6), disability, new illness, poor health status, prior depression, bereavement, and sleep disturbance (7). Depressive symptoms are more prevalent among college students than the general population, and Iranian college students are not an exception; meta-analyses and systematic reviews have estimated a prevalence of 33% [95% confidence interval (CI): 32 - 34%] for depressive symptoms among Iranian college students (8). Some of the symptoms of the condition include sadness, hopelessness, nervousness, anxiety, and boredom (9).

A wide range of causes, both environmental and personal, can account for this noticeable prevalence. Less close contact with parents or intimate friends, inadequate facilities, and the challenges of adjusting to the new environment (e.g. those associated with living in the dormitory) are examples of environmental causes of depression. Problems related to individual factors include the stress associated with the need to make high achievements, uncertainties about the future, lack of interest in the field of study, genetics, family history, gender, socio-economic status (SES), nutritional habits, and risky behaviors (e.g. drug abuse, alcoholism, smoking) (10-12).

2. Objectives

The prevalence of depression seems to be increasing among students (13). According to a report, the prevalence of depression among Iranian college students did not increase between 1995 and 2012. However, numerous studies have dealt with the subject since then, a fact that implies the importance of the issue (8). One shortcoming with this report, however, is that some predictive factors of depression have not been considered, nor has the evaluation method of depressive disorders, as an important factor that may affect measuring this phenomenon (8). In addition, comparing the results of this study with the current one, which has been conducted after six years, would provide useful information.

Although a growing number of studies have investigated the prevalence of depression among university students, little is known about its overall country-wide prevalence. In summary, the current study aimed to, firstly, investigate the prevalence of depression among Iranian college students, and secondly, discussing some risk factors related to depression (e.g. age, gender, and marital status). Besides, there is evidence that some factors like living in the dormitory are likely to promote depressive disorder. Moreover, in the present study, the methodology used to measure the severity of depression disorder (which has a key role in detecting depression), the severity of depression, university category (a potential factor that is rarely considered by previous studies), and level of interest in the field of study were all taken into account. Hence, we performed a meta-analysis in order to bring together the factors that potentially affect the prevalence of depression among Iranian university students with the aim of providing useful information for developing future research priorities.

2.1. Data Sources

The present study contained several stages including precise problem definition, collection, analysis, and interpretation of the results, and reporting a guide for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) (14). In order to avoid potential biases, search steps, selection of studies, quality assessment, and data extraction were performed by two independent researchers (J.Z and M.F). In case of a disagreement, a consensus was reached through discussion or, if necessary, the third reviewer was consulted (MM).The final decision was reached following a group discussion.

3. Evidence Acquisition

3.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We systematically searched international [i.e. PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Web of Science (ISI), Embase, and Google Scholar] and national [i.e. Scientific Information Database (SID), Magiran, Iranmedex, and Iranian Research Institute for Information Science, and Technology (IranDoc)] databases for the period of 1991 to 2019 in order to identify relevant studies. In order to increase the comprehensiveness of the search, medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and their Persian equivalents were used. The search strategies were (“Depression” [Title/Abstract] OR “Depressive Symptoms” [Title/Abstract] OR “Mental health” [Title/Abstract] OR “Mental disorder” [Title/Abstract] OR “Risk factor” [Title/Abstract] OR “Students” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Prevalence” [Title/Abstract] OR “Epidemiology” [Title/Abstract]) AND (“Iran” [Title/Abstract/Affiliation]). We also hand-searched the reference list of the selected articles in order to increase the chance of finding potentially relevant studies related to the topic under scrutiny. All eligible articles were included in the systematic review.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were developed based on (evidence-based medicine) the PICO (15), which included: (1) P, quantitative cross-sectional studies on the depression of Iranian college students; (2) I, instruments used in the measurement of depression, which included questionnaires Beck Depression Inventory [Beck (II)], Beck Depression Inventory [Beck (I)], General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90- R), and depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21); (3) C, comparative groups based on gender, marital status and university type; and (4) O, studies that estimated the Prevalence of depression in Iranian college students.

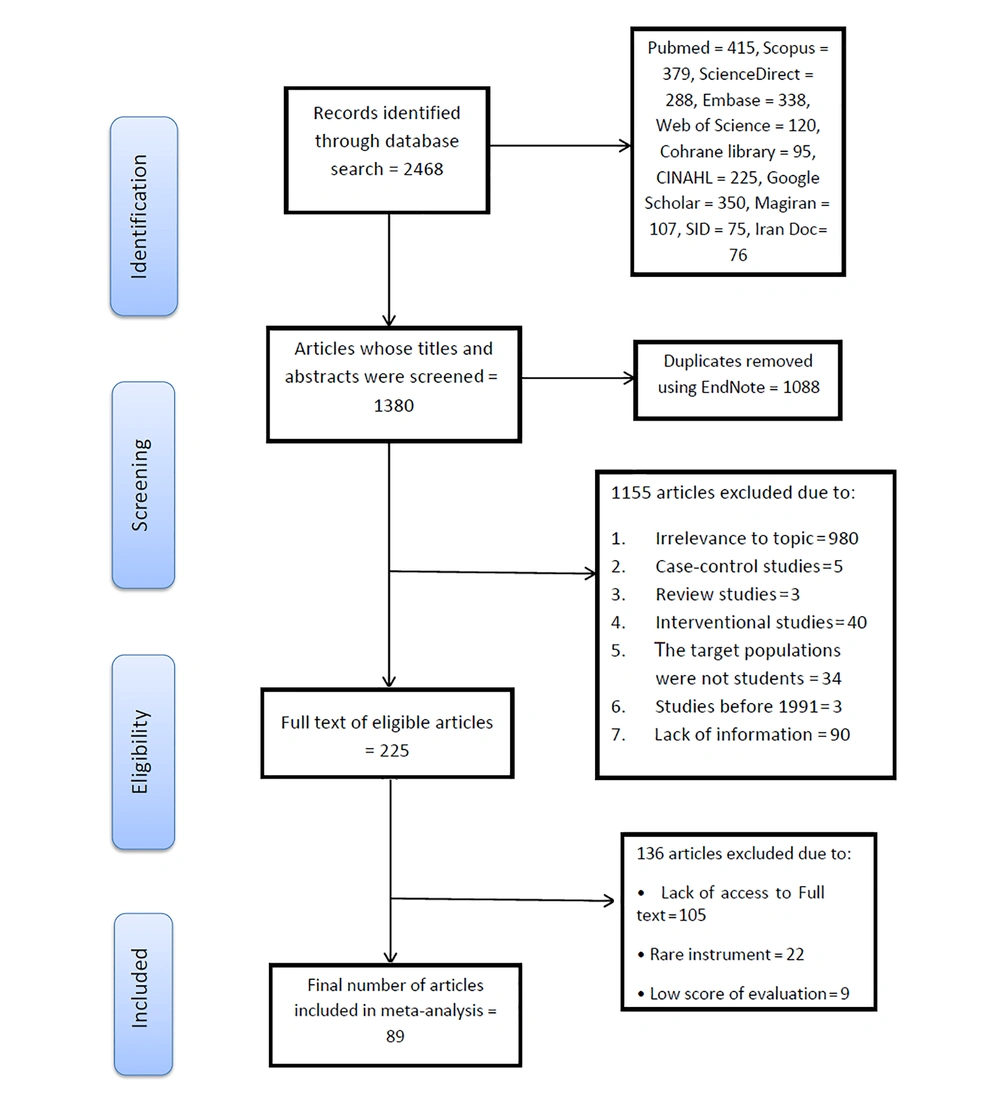

Exclusion criteria included repetitive articles, irrelevant articles, having a design other than non-cross-sectional, inaccessibility of the full text of the study, not investigating a sample of students, studies published before 1991, not reporting the prevalence of depression and its related factors (e.g. studies that only have reported prevalence depression), studied with a poor design, studies that have used rare data collection tools (e.g. Znug’s self-rating depression scale (Zung), which was used in 3 articles, depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-42), which was used in 1 article, university student depression inventory (USDI), which was used in 1 article, Ahwaz depression inventory (ADI), which was used in 1 article, Mood and Anxiety Symptom questionnaire, which was used in 2 articles, Symptom Checklist-25 (SCL-25), which was used in 1 article, Tehran multidimensional perfectionism scale (TMPS), which was used in 1 article, the cognition checklist, Middlesex Hospital questionnaire, which was used in 3 articles, Hopkins symptom checklist, which was used in 1 article, Hamilton questionnaire, which was used in 2 articles, and studies that have used Beck’s Questionnaire without mentioning its type (i.e. type 1 or 2) (Figure 1).

3.3. Study Selection

A total of 2,468 articles were identified, of which 1,088 were excluded. Of the remaining 1,380 articles, 225 articles proved eligible. Following an evaluation of the quality of the latter articles, 89 entered the meta-analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process using the PRISMA flow diagram, which consists of four main stages: identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion (14).

3.4. Quality Assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) checklist (16) was used to evaluate the quality of identified studies. NOS contains three sections with the following contents: (1) study selection (four items), (2) comparability (one item), and (3) outcome (two items). Studies with a score of NOS ≥ 7 are of high quality; 5 < score < 6 are of moderate quality, and those with a score of NOS < 5 (which were excluded) are of poor quality. In this study, two authors (J.Z and M.F) reviewed the full text of identified articles. In case of a disagreement, a consensus was reached through discussion or, if necessary, the third reviewer was consulted (MM). Articles with a low score quality, based on the NOS checklist, were excluded.

3.5. Data Extraction

A checklist was developed for data extraction, which included items on the first author, year of publication, implementation year, type of study, study design, sample size, location of study, type of university [university of medical sciences (which are under the authority of the Ministry of Health); public universities (which are affiliated to the Ministry of Science Technology and Research and are financially supported by the government); Islamic Azad University (a non-governmental university that is privately run on student tuition fees); Payame Noor University (a semi-private university, a public university where the training is semi-private)], method of measuring depression, the prevalence of depression, mean and standard deviation of age, and some other depression-related factors. The extracted information was independently reviewed by two researchers (M.H and D.E). In cases of ambiguity, the authors of the articles were contacted.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

The binomial distribution was used to calculate the variance of each study. To assess the heterogeneity of identified studies, Cochran’s Q test, I2, and τ2 statistics were used. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies, a random-effects model was used to estimate the prevalence of depression (17, 18). Sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the effect of excluding one study on the overall estimate at a time (19). In order to identify the cause of heterogeneity of prevalence of depression, sub-group analysis of depression was performed based on gender, level of depression, type of applied questionnaires, and the type of university. In addition, the meta-regression model was used to investigate the prevalence of depression based on the year of study. Moreover, publication bias was assessed by Begg’s test. All the analyses were performed using the comprehensive meta-analysis (CMA) version 2.2 software while adopting a significance level of < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of Eligible Studies

A total of 89 articles was included, with a total of 33,564 Iranian college students were eligible for the review. The mean age of subjects investigated in 60 studies (for which information were available) was 21.84 years (95% CI: 21.60 - 22.08%). The characteristics of eligible studies are provided in Table 1.

| Study | Study Design | Study Location | Total Sample Size (N) | Age (Mean ± SD) | Questionnaire | Quality Scores (NOS) | Prevalence of Depression (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi (20) | Cross-sectional | Ahvaz | 200 | NA | Beck Depression Inventory [Beck (II)] | 6 | 45.0 |

| Molavi et al. (21) | Cross-sectional | Ardabil | 269 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 57.6 |

| Hashemi and Kamkar (22) | Cross-sectional | Yasuoj | 421 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 69.1 |

| Fakhari (23) | Cross-sectional | Tabriz | 600 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 42.0 |

| Yousefnazari (24) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 402 | NA | Beck Depression Inventory [Beck (I)] | 5 | 99.9 |

| Musarezaie et al. (25) | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | 715 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 44.1 |

| Heidaripahlavian et al. (26) | Cross-sectional | Hamadan | 386 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 43.5 |

| Ildarabady et al. (27) | Cross-sectional | Zabul | 157 | NA | Beck (II) | 7 | 64.3 |

| Karami (28) | Cross-sectional | Kashan | 208 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 50.0 |

| Rezaei et al. (29) | Cross-sectional | Hamadan | 222 | 21.87 ± 1.95 | Beck (II) | 6 | 54.5 |

| Najafi Kalyani et al. (30) | Cross-sectional | Fasa | 179 | NA | Depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21) | 5 | 53.1 |

| Amani et al. (31) | Cross-sectional | Ardabil | 324 | 20.80 ± 1.58 | Beck (II) | 5 | 57.4 |

| Hasanzadeh et al. (32) | Cross-sectional | Birjand | 231 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 12.1 |

| Dadkhah et al. (33) | Cross-sectional | Ardabil | 409 | 20.03 ± 1.20 | Beck (II) | 5 | 49.9 |

| Khoshkhati et al. (34) | Cross-sectional | Zanjan | 52 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 32.7 |

| Khoshkhati et al. (34) | Cross-sectional | Zanjan | 31 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 32.3 |

| Ahmari Tehran et al. (35) | Cross-sectional | Ghom | 250 | 21.42 ± 2.75 | Beck (II) | 5 | 55.2 |

| Abedini et al. (36) | Cross-sectional | Bandarabbas | 190 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 54.7 |

| Najafipour and Yektatalab (37) | Cross-sectional | Jahrom | 150 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 36.0 |

| Zamanian Z et al. (38) | Cross-sectional | Shiraz | 358 | 20.71±2.07 | Beck (II) | 5 | 45.3 |

| Azarniveh and Tavakoli Khomizi (39) | Cross-sectional | Zabul | 375 | 21.85 ± 3.49 | Beck (II) | 5 | 44.8 |

| Rahmani Bidokhti et al. (40) | Cross-sectional | Birjand | 151 | 22 ± 2 | Beck (I) | 5 | 31.8 |

| Foroutani (41) | Cross-sectional | Larestan | 134 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 42.5 |

| Tavakolizadeh and Mohammadpour (42) | Cross-sectional | Gonabad | 291 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 62.5 |

| Hashemi Mohamm adabad et al. (43) | Cross-sectional | Yasuoj | 452 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 61.9 |

| Rafati et al. (44) | Cross-sectional | Jiroft | 173 | 21.30 ± 1.90 | Beck (II) | 5 | 59.0 |

| Mohtashamipour et al. (45) | Cross-sectional | Mashhad | 256 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 45.3 |

| Behdani et al. (46) | Cross-sectional | Sabzevar | 264 | 21.56 ± 2.65 | Beck (II) | 6 | 75.4 |

| Oskouei and Kahkeshan (47) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 393 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 36.1 |

| Mokhtari et al. (48) | Cross-sectional | West Azerbaijan | 3859 | NA | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) | 5 | 8.5 |

| Aghakhani et al. (49) | Cross-sectional | Urmia | 628 | 22 ± 0.30 | Beck (II) | 7 | 52.5 |

| Mohammadzadeh (50) | Cross-sectional | Ilam | 381 | 21 ± 0.99 | Beck (II) | 5 | 76.4 |

| Jalilian et al. (51) | Cross-sectional | Hamadan | 235 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 37.0 |

| Parvaresh et al. (52) | Cross-sectional | Kerman | 414 | NA | Beck (II) | 7 | 24.4 |

| Eslami et al. (53) | Cross-sectional | Jahrom | 356 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 39.0 |

| Eslami et al. (54) | Cross-sectional | Gorgan | 193 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 45.1 |

| Sharifi et al. (55) | Cross-sectional | Kashan | 307 | NA | Beck (I) | 6 | 35.8 |

| Dehdari et al. (56) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 222 | 23 ± 3.60 | DASS-21 | 6 | 59.5 |

| Azizi et al. (57) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 130 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 52.3 |

| Baghiani et al. (58) | Cross-sectional | Yazd | 125 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 42.4 |

| Rahnamay Namin (59) | Cross-sectional | Takestan, Abhar and Booyinalzahra | 407 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 65.8 |

| Ghasemnegad and Barchordary (60) | Cross-sectional | Gilan and Lahijan | 150 | NA | Beck (II) | 7 | 48.0 |

| Masoudi Asl (61) | Cross-sectional | Yasuoj | 200 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 49.0 |

| Mogharab et al. (62) | Cross-sectional | Birjand | 400 | 22 ± 3 | Beck (II) | 6 | 45.0 |

| Nourouzi Eghdam (63) | Cross-sectional | Miyaneh | 318 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 66.0 |

| Sam et al. (64) | Cross-sectional | Kerman | 376 | 20.20 ± 2.20 | Beck (II) | 5 | 46.0 |

| Mazahari et al. (65) | Cross-sectional | Rafsanjan | 310 | 20.57 ± 1.56 | Beck (II) | 6 | 37.1 |

| Safari et al. (66) | Cross-sectional | Kermanshah | 356 | 20.73 ± 2.63 | DASS-21 | 5 | 69.7 |

| Ghorban Alizadeh Ghaziyani et al. (67) | Cross-sectional | Multiple | 180 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 67.8 |

| Rashidi Zaviyeh (68) | Cross-sectional | Zanjan | 148 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 50.0 |

| Miri et al. (69) | Cross-sectional | Birjand | 390 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 57.4 |

| Jazayeri and Ghahari (70) | Cross-sectional | Tankabon | 120 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 29.2 |

| Salmani Barough et al. (71) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 67 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 26.9 |

| Foroughan et al. (72) | Cross-sectional | Bandarabbas | 271 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 43.9 |

| Rezaei Adaryani et al. (73) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 223 | 25.30 ± 2.68 | DASS-21 | 6 | 51.6 |

| Rafati et al. (74) | Cross-sectional | Shiraz | 307 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 59.9 |

| Rezayat and Dehgannayeri (75) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 249 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 38.6 |

| Mehri and Sadighi Soumeh Kouchak (76) | Cross-sectional | Sabzevar | 270 | 23.42 ± 3.63 | GHQ-28 | 6 | 23.7 |

| Basati MA et al. (77) | Cross-sectional | Kermanshah | 260 | NA | DASS-21 | 6 | 26.9 |

| Bahrami et al. (78) | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | 300 | NA | GHQ-28 | 5 | 22.3 |

| Mortazavi Tabatabaei et al. (79) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 390 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 49.7 |

| Maleki et al. (80) | Cross-sectional | Hamadan | 1191 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 27.1 |

| Babadi-Akashe et al. (81) | Cross-sectional | Shahrekord | 296 | NA | Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL-90- R) | 5 | 17.2 |

| Mousavi et al. (82) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 205 | 24.70 ± 1.69 | GHQ-28 | 7 | 25.4 |

| EyvanBaga et al. (83) | Cross-sectional | Khalkhal | 202 | NA | Beck (II) | 7 | 21.8 |

| Faraji et al. (84) | Cross-sectional | Ardabil | 300 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 57.7 |

| Golzar et al. (85) | Cross-sectional | Shiraz | 200 | 21.66 ± 11.20 | Beck (II) | 6 | 64.0 |

| Hosanei et al. (86) | Cross-sectional | Mazandaran | 285 | NA | GHQ-28 | 5 | 89.8 |

| Khushde et al. (87) | Cross-sectional | Sistan and Baluchestan | 204 | NA | Beck (II) | 7 | 93.1 |

| Mousavi et al. (88) | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | 435 | 21.78 ± 2.33 | Beck (II) | 7 | 28.0 |

| Ajilchi and Nejati (89) | Cross-sectional | Tehran | 122 | NA | DASS-21 | 5 | 24.6 |

| Poorolajal et al. (90) | Cross-sectional | Hamadan | 1259 | NA | GHQ-28 | 7 | 24.1 |

| Jafari et al. (91) | Cross-sectional | Shiraz | 477 | NA | DASS-21 | 7 | 35.6 |

| Jamshidi et al. (92) | Cross-sectional | Ahvaz | 781 | NA | GHQ-28 | 7 | 11.7 |

| Hashemi Mohammad Abad et al. (93) | Cross-sectional | Yasuoj | 464 | NA | Beck (II) | 5 | 63.8 |

| Talaei et al. (94) | Cross-sectional | Mashhad | 1200 | NA | Beck (II) | 6 | 32.2 |

| Imani et al. (95) | Cross-sectional | Hormozgan | 95 | 21.12 ± 1.44 | GHQ-28 | 5 | 17.9 |

| Parvizrad et al. (96) | Cross-sectional | Mazandaran | 334 | NA | GHQ-28 | 6 | 47.9 |

| Safiri et al. (97) | Cross-sectional | Tabriz | 175 | NA | Beck (I) | 8 | 78.3 |

| Zolfaghari et al. (98) | Cross-sectional | Toyserkan | 400 | NA | SCL-90-R | 5 | 72 |

| Hadavi et al. (99) | Cross-sectional | Rafsanjan | 250 | 19.92 ± 1.66 | SCL-90-R | 5 | 23.6 |

| Jahani hashemi et al. (100) | Cross-sectional | Qazvin | 314 | NA | SCL-90-R | 6 | 75.2 |

| Jahani hashemi et al. (100) | Cross-sectional | Qazvin | 293 | NA | SCL-90-R | 6 | 67.9 |

| Tabrizizadeh et al. (101) | Cross-sectional | Yazd | 191 | NA | SCL-90-R | 6 | 39.3 |

| Hojjatoleslami and Ghodsi (102) | Cross-sectional | Hamadan | 280 | 22 ± 3.5 | Beck (II) | 6 | 73.6 |

| Ghaedi and MohdKosnin (103) | Cross-sectional | Isfahan | 400 | 21.45 ± 1.66 | Beck (II) | 5 | 40.0 |

| Tavakolizadeh et al. (104) | Cross-sectional | Gonabad | 700 | NA | GHQ-28 | 6 | 29.7 |

| Yousefi and Mohamadkhani (105) | Cross-sectional | Sanandaj | 1000 | NA | GHQ-28 | 6 | 99.4 |

| Bahrami et al. (106) | Cross-sectional | Semnan | 177 | 22.15 ± 3.88 | Beck (II) | 7 | 80.2 |

| Mohebian et al. (107) | Cross-sectional | Zanjan | 149 | 21.7 ± 2.28 | DASS-21 | 6 | 31.5 |

| Hadavi and Rostami (3) | Cross-sectional | Rafsanjan | 400 | 20.78 ± 2.37 | Beck (II) | 6 | 50.7 |

Abbreviation: NA, not available.

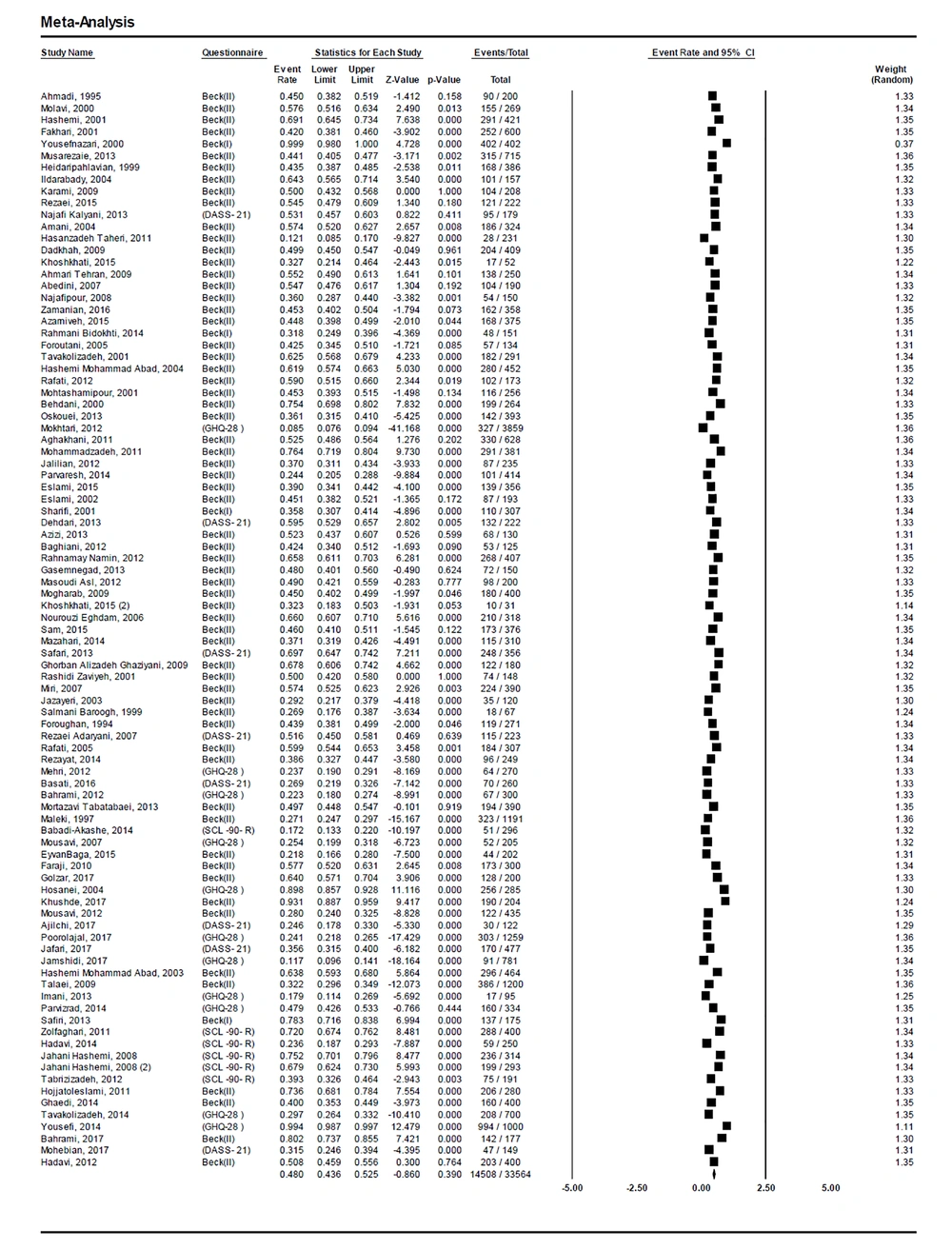

4.2. Total Prevalence of Depression

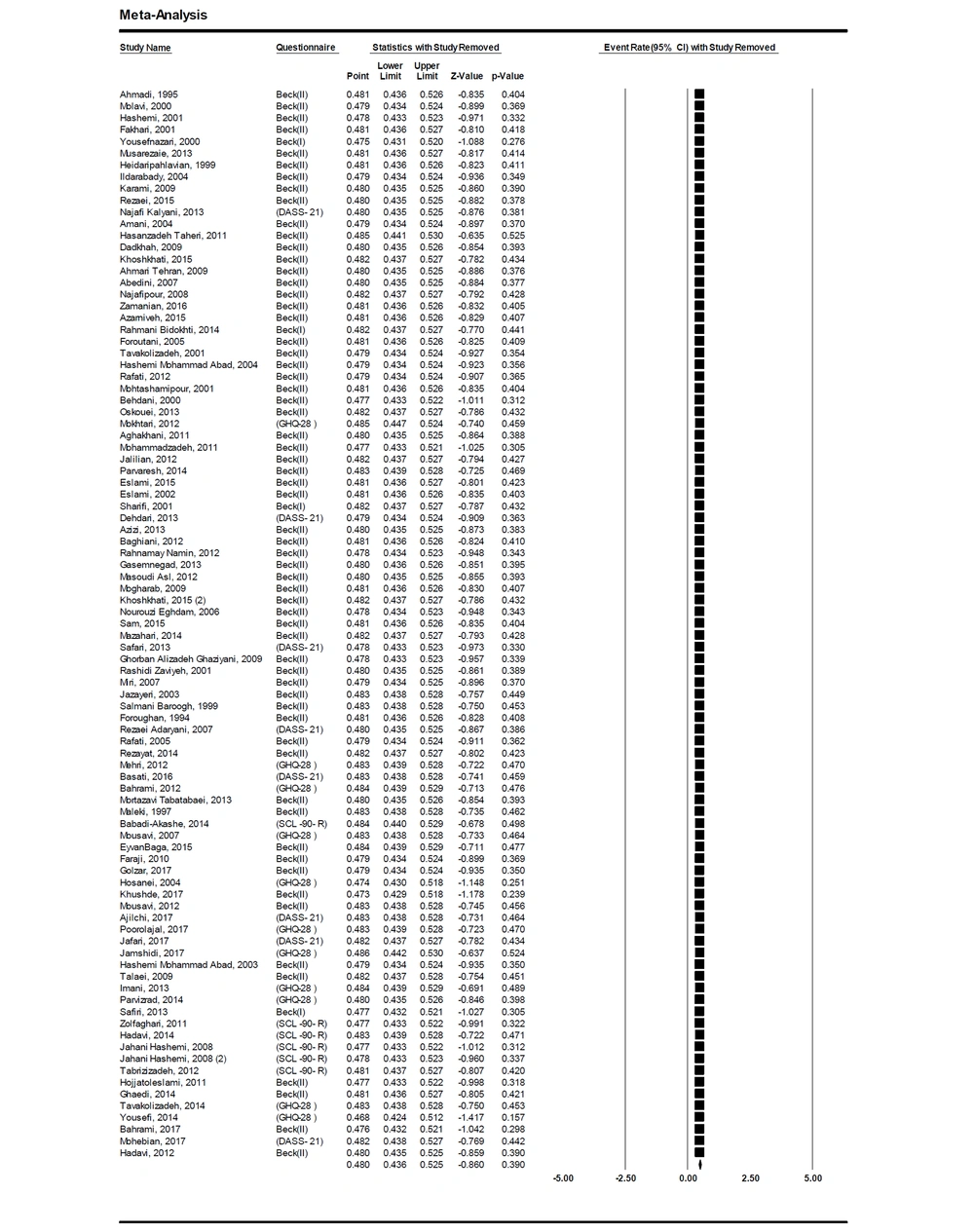

The overall pooled crude prevalence, which was defined as the event rate of depressed people to the total sample of studies on university students, was estimated as 48.0% (95% CI: 43.6 - 52.5%), and the heterogeneity (I2) was 98.08% (P < 0.001 and τ2 = 0.731), (Figure 2). According to the sensitivity analysis for the prevalence of depression, after removing a study at a time, the results were still robust (Figure 3).

4.3. Subgroup Analysis Based on Gender

Prevalence of depression among males and females was 51.3% (95% CI: 41.1 - 61.4%) and 48.9% (95% CI: 41.0 - 54.8%), respectively. The results of the subgroup analysis revealed no significant difference between males and females concerning the prevalence of depression (P = 0.589) (Table 2).

| Variables | Studies (N) | Sample (N) | Heterogeneity | 95% CI | Prevalence (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | P-Value | τ2 | |||||

| Gender a | |||||||

| Male | 33 | 6593 | 97.57 | < 0.001 | 1.390 | 41.1 - 61.4 | 51.3 |

| Female | 41 | 11930 | 97.58 | < 0.001 | 0.778 | 41.0 - 54.8 | 48.9 |

| Intensityb | |||||||

| Mild | 68 | 20861 | 92.90 | < 0.001 | 0.232 | 23.8 - 28.6 | 26.1 |

| Moderate | 68 | 20861 | 96.17 | < 0.001 | 0.634 | 13.1 - 18.3 | 15.5 |

| Severe | 68 | 20861 | 95.06 | < 0.001 | 0.938 | 5.1 - 8.0 | 6.4 |

| Questionnaires c | |||||||

| Beck (II) | 62 | 19709 | 96.10 | < 0.001 | 0.344 | 45.7 - 53.2 | 49.5 |

| Beck (I) | 4 | 1035 | 97.26 | < 0.001 | 1.308 | 38.8 - 88.1 | 68.4 |

| GHQ-28 | 11 | 9088 | 99.09 | < 0.001 | 1.303 | 24.6 - 56.1 | 39.2 |

| DASS-21 | 8 | 1988 | 96.22 | < 0.001 | 0.473 | 32.3 - 55.8 | 43.7 |

| SCL-90-R | 6 | 1744 | 98.56 | < 0.001 | 1.237 | 27.8 - 69.8 | 48.5 |

| Type of university d | |||||||

| University of medical science | 61 | 19819 | 97.14 | < 0.001 | 0.515 | 41.8 - 51.0 | 46.3 |

| Public university | 7 | 3360 | 98.25 | < 0.001 | 0.597 | 44.1 - 71.7 | 58.6 |

| Islamic Azad University | 8 | 2309 | 95.95 | < 0.001 | 0.462 | 41.5 - 66.2 | 54.1 |

| Payame Noor University | 2 | 4259 | 99.85 | < 0.001 | 5.517 | 1.8 - 92.7 | 32.8 |

| Various university | 13 | 3817 | 97.54 | < 0.001 | 0.640 | 37.2 - 58.9 | 47.9 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; N, number.

a Test for subgroup differences; Q = 0.292, df (Q) = 1, P = 0.589.

b Test for subgroup differences; Q = 148.092, df (Q) = 2, P < 0.001.

c Test for subgroup differences; Q = 3.777, df (Q) = 4, P = 0.437.

d Test for subgroup differences; Q = 3.593, df (Q) = 4, P = 0.464.

4.4. Subgroup Analysis Based on the Intensity

According to the definitions provided for levels of depression in the literature, the prevalence of mild, moderate, and severe depression among university students was estimated at 26.1% (95% CI: 23.8 - 28.6%), 15.5% (95% CI: 13.1 - 18.3%), and 6.4% (95% CI: 5.1 - 8.0%), respectively. We also found a significant difference between males and females (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

4.5. Subgroup Analysis Based on Questionnaires

In the present study, the prevalence of depression based on the type of data collection tool (i.e. questionnaire) was also evaluated. According to the findings, the highest and lowest prevalence rates of depression belonged to Beck-I [68.4% (95% CI: 38.8 - 88.1%)] and GHQ-28 [39.2% (95% CI: 24.6 - 56.1%)], respectively. However, there was no significant difference in the subgroup analysis (P = 0.437) (Table 2).

4.6. Subgroup Analysis Based on Type of University

The highest and lowest prevalence rates of depression were found among students of Public Universities (58.6%; 95% CI: 44.1 - 71.7%) and Payame Noor University (32.8%; 95% CI: 1.8 - 92.7%), respectively. The results revealed no significant difference (P = 0.464) (Table 2).

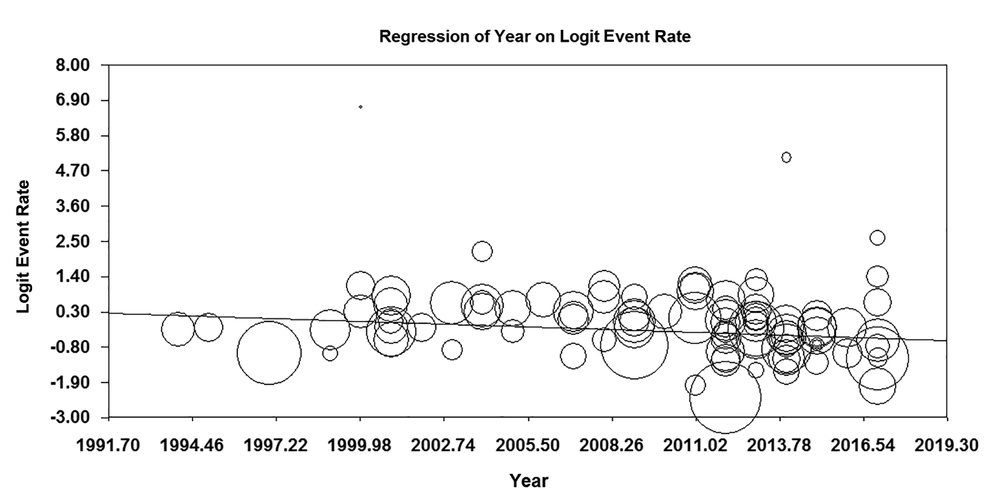

4.7. Meta-regression

According to the results of the meta-regression, the prevalence of depression among Iranian university students has been significantly increased during the study period (P < 0.001) (Figure 4).

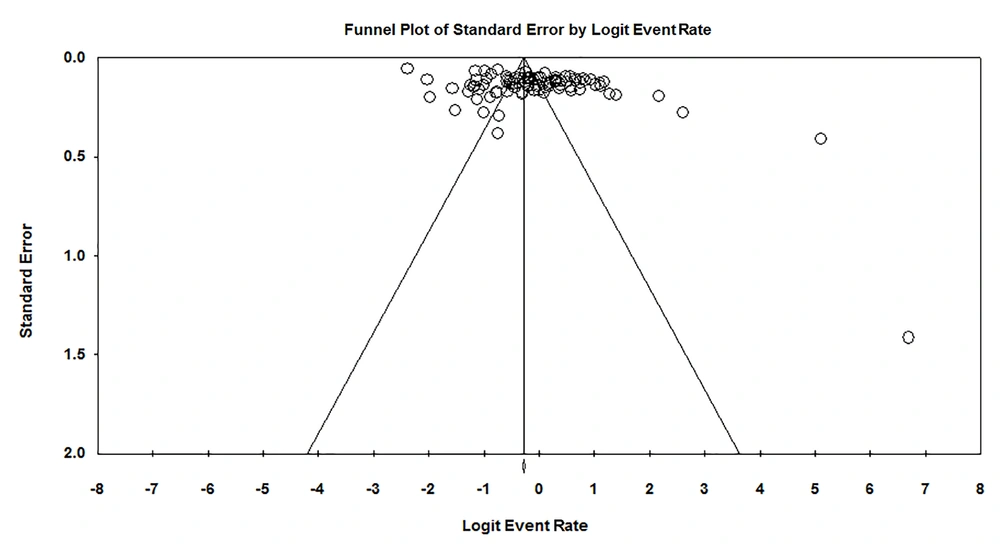

4.8. Publication Bias

The P-value for publication bias in Begg’s tests was estimated at 0.675, which was not statistically significant (Figure 5).

4.9. Factors Related to the Depression

The meta-analysis results of evaluating factors related to depression are provided in Table 3. According to the findings, students ‘interest in the field’ had a significant negative correlation with depression (P < 0.001).

| Variables | Studies (N) | Sample (N) | Heterogeneity | OR (95% CI) | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | I2 | P-Value | τ2 | ||||

| Marital status | 11 | 1894 | 1485 | 91.04 | < 0.001 | 1.363 | 1.25(0.59 - 2.62) | 0.54 |

| Native status | 10 | 1312 | 1074 | 61.82 | 0.005 | 0.188 | 0.70(0.49 - 1.01) | 0.059 |

| Interest in the field | 7 | 683 | 695 | 55.52 | 0.03 | 0.214 | 0.32(0.20 - 0.52) | < 0.001 |

| Age group (y) | ||||||||

| < Or > 20 | 6 | 1394 | 1175 | 66.41 | 0.01 | 0.121 | 0.83(0.58 - 1.18) | 0.31 |

| < Or > 25 | 6 | 1279 | 1228 | 61.10 | 0.02 | 0.208 | 1.03(0.62 - 1.70) | 0.90 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; N, number.

5. Discussion

According to the findings of the present study, about half of the Iranian university students suffer from depression, as evidenced by presented symptoms. Although the results were somehow heterogeneous, the results of the subgroup analysis showed that depression intensity may lead to high heterogeneity. However, this difference may be due to the characteristics (i.e. size) of study samples. It is also accounted for by different measurement tools and various employed methods.

According to the results of systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted in other countries, the prevalence of depression among university students ranges from 20 to 31.8% (108-110), indicating that the prevalence in Iranian college students is higher than that in other countries. Besides, based on previous studies, Asians are less likely to report their depression than people in western countries (111). However, the prevalence of depression among Chinese university students is reported at 23.8% (95%; CI: 19.9 - 28.5%), which is lower than that in our study (108). This difference may be due to cultural differences and ethnicity, lack of suitable good jobs and/or lack of social support in achieving them, as well as unfavorable economic conditions. Failure to meet course requirements is another potential cause of depression. Differences in the investigation and follow-up processes of depressed people in Iran, as compared to other countries, and/or in the quality of provided prevention and treatment services probably have contributed to the observed difference.

On the other hand, a systematic review of 35 studies (with a total of 9,743 subjects) in Iran for the period of 1995 to 2012 reported a prevalence of 33% (95% CI: 32 - 34%) for depression among Iranian university students (8). In the present meta-analysis, which combined 89 studies with a sample size of 33,564 Iranian college students, the prevalence of depression was 48.0% (95% CI: 43.6 - 52.5%). According to previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted on university students, it seemed reasonable to perform a new systematic review and meta-analysis after six years. In Sarokhani’s study, only 35 studies, with 9,743 participants, are reviewed (8), while at that time more than fifty related articles were published. In another previous study, the prevalence of depression has been estimated at about 33%, while in our study, the prevalence of depression was estimated at 48.0%, which indicates a significant increase. By comparing our results with previous findings, it seems that the trend of depression disorder has increased among Iranian university students, especially when findings were interpreted separated by gender, which the prevalence of depression amounted to more than 50% among males. In addition, the strengths of this study, compared to previously published meta-analyses, are benefiting from a relatively larger sample size, investigating more recent studies, and covering studies that have used different data collection tools.

Findings regarding the association between age and the occurrence of depression are inconsistent. Although some studies reported the effect of age on depression, some others mentioned the interactive effect of age with income, childhood abuse index, pain, body mass index, and the number of chronic diseases. That is, the effect of these factors is larger than that of age. In this study, most articles did not mention age, but based on our analysis, we did not find any significant association within age groups. It worth noting that most students cover a limited age range (18 to 30 years old), which may be a reason for not finding any association between age and depression (112).

We found no significant difference between male and female students regarding the prevalence of depression, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (113-115). However, contrary to our findings, some studies reported higher rates of depression among female university students (116). On the other hand, a previous systematic review and meta-analysis found a higher prevalence of depression among male university students than in females (8), which is consistent with our findings. Furthermore, previous findings mentioned male gender as an important risk factor of suicidal ideation (117), as well as alcohol and drug abuse (118).

The association between marital status and depression symptoms is well documented (119). However, the clinical findings mentioned the contribution of other factors. For instance, this association is modified by age and gender (120). Although in the present study little information were available about marital status and most studies did not address the marital status of their participants, we did not find any significant association between marital status and depression. The prevalence rates of depression among Iranian university students at different levels of intensity were estimated at 26.1, 15.5, and 6.4% for mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively. The fact that most of the depressed people have mild symptoms suggests that clinical and psychological programs and treatments could prevent the development of depression among Iranian university students, which in turn prevented the further consequences of the disease.

In the present study, the reported rates of depression prevalence among Iranian university students ranged from 39.2 to 68.4%. The most probable cause of such a wide range of prevalence is the diversity of applied diagnostic tools, including Beck-II, Beck-I, GHQ-28, SCL-90- R, and DASS-21. For instance, in the study by Ghaedi et al. (103), who used the Beck-II questionnaire to assess depression, a prevalence of 40% is reported, while in studies that had used the GHQ-28 questionnaire, a prevalence of 29.7 is reported (104). In our study, the subgroup analysis, according to the applied questionnaires, did not provide significant results.

The highest and lowest prevalence rates of depression were in students of public universities [58.6% (95% CI: 44.1 - 71.7%)] and Payame Noor University [32.8% (95% CI: 1.8 - 92.7%)], respectively. This difference can be attributed to the higher academic pressure in public universities as compared to Payame Noor University. In fact, studying at public universities is much more competitive and highly more demanding than at other universities, including Payame Noor University. In addition, graduates of public universities are expected to find better jobs.

In this study, a meta-regression model was used to find the prevalence of depression among university students vis-a-vis the year of study. There was a significant association between the prevalence of depression among university students and the year of study. This may be due to increased economic pressures and inadequate economic conditions of families, reduced physical activity, as well as nutritional factors like consumption of more fast food during college education. Findings also suggested that negative life events, such as failure in love, separation of parents, and financial problems, are direct sources of depression. University students with more negative life experiences are at an increased risk of developing depression (121). In addition, the study by Lipson et al. (2018), which examined the healthy minds study (HMS) of US students over a ten-year period (2007 - 2017), indicated an increase in depression among college students, which is in line with the results of the present study (122).

Various factors contribute to the development of depression. In the present study, interest in the field of study had a significantly reverse association with depression among Iranian university students, which is similar to the results of other studies (27, 43, 58, 60, 72, 97, 106), which in turn indicates that educating the students on how to select a field of study before entering the university can reduce depression prevalence among university students. The results of these studies also show that families should not force their children to study in a field that they are not interested in. Because studying a field that is not interested, not only prevents them from success, but also may cause health problems (58). Starting university education requires several changes and adjustments in such a way that students can enter their favorite fields of study without too much difficulty. Families, and society at a wider spectrum, should also respect students’ preferences more and simultaneously avoid putting pressure on them in making their academic choices.

5.1. Strengths and Limitations

It is necessary to mention some strengths and limitations of our study. One of the most important strengths is performing a more comprehensive literature review. Besides, a more systematic methodology has been employed in treating the collected data, one that includes a range of meta-analyses. The present study entails, however, a number of inevitable limitations. Firstly, the national databases did not provide the possibility of doing a combined search. Secondly, some risk factors (e.g. the history of depression, religious orientations, and familial economic conditions) could not be included in the analyses as few studies have addressed such issues. This points to the need for more qualitative studies to explore other factors associated with the prevalence of depression among Iranian university students to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the problem.

In Conclusion, the findings of this review point to the fact that the prevalence of depression among Iranian college students is high. The review not only highlights the existing gaps in the literature on depression among Iranian college students, but also the need for interventions to reduce the prevalence rate of depression in universities. Future studies in this field should more focus on the characteristics of the participants to find key factors that contribute to the prevalence of depression. We hope this meta-analysis, which summarized research findings published over the past 25 years, can serve as a warning to university administrations. The results of our study should stimulate not only more research on university students, as a distinct group, but also encourage families, universities, and society, as a whole, to develop and implement strategies to help the young to overcome their difficulties, which in turn leads to a healthier life.