1. Context

Pregnancy and childbirth are essential physiologic, social, and emotional aspects of a woman’s and her family members’ lives (1). Considering its intrinsic nature as an unpredictable and painful event with a high risk of serious complications and even death (2), childbirth is known as a stressful condition (3). This notion regarding childbirth is also applicable to fathers. The comprehension of childbirth and the ways of compromising with it in men are variable (4). Childbirth can lead to both favorable and unfavorable feelings, with the predominance of favorable ones in men. Although the first moments after childbirth have been declared as the best moments of men’s life (4), these moments can turn into dreadful and concerning events (5). The husband of the pregnant woman may experience Couvade syndrome, which is manifested as the loss of appetite, nausea, irritability, anxiety, excitement, headaches, and sleep disturbances that closely simulate those of pregnancy (6, 7).

According to the definition by Barlow, fear and anxiety are the states of helplessness feeling complicating with perceived inability to predict, control, or obtain the desired outcomes in critical moments in the future (8). Anxiety is a response to a risk position that is characterized by doing Ego's work to avoid that position (9). Symptoms are created to prevent anxiety. In fact, symptoms have been created to prevent a dangerous situation that has been reported with anxiety (9).

The Fear of Childbirth (FOC) is a psychological disorder categorized into mild to severe intensities (10). In the case of severe FOC, it can be both physically and emotionally debilitating, leading to pathological conditions such as “tokophobia” (11). Tokophobia is comprised of the words “tokos” (a Greek word meaning childbirth) and “phobia” (12). “Maieusiophobia” and “ parturiphobia” are two other names for this condition (5). Tokophobia is considered by its proponents to be a “non-logical FOC” (9, 13). Although tokophobia was first defined in the 18th century, there is no consensus on its precise definition (14). For the first time, tokophobia was described by British phycologists in 1999. However, the word “tokophobia” as a medical condition was first used by Hofberg and Brockington in 2000 (11). Nevertheless, FOC had also been described by Marcé, a French psychologist, in 1858 (12).

Currently, tokophobia has been assigned the code of F40.9 in 2015, ICD-10-CM, as an unclassified phobic anxiety disorder (14, 15). Primary tokophobia is a dreadful FOC in the first pregnancy (16). Published evidence from India shows that a larger proportion (78.4%) of first-time expectant fathers suffered from tokophobia (3). In contrast to primary tokophobia, “secondary tokophobia” is usually observed after traumatic childbirth (16).

Although tokophobia may also be seen in men, most studies have been focused on mothers (17). The etiology of tokophobia in fathers may be related to fears regarding the safety of the mother and child, the course of labor and childbirth, receiving inadequate medical services, and insecurity regarding his/her spouse’s abilities (3, 11). Fathers play a key role in supporting their partner in pregnancy, labor, and childbirth, and their needs are equally important as the mothers’ needs (3). Considering that anxiety and FOC in fathers may also debilitate them in supporting the spouse and therefore negatively influence childbirth, it is necessary to address this problem. Nevertheless, tokophobia and its related complications have been less studied in fathers (18). Therefore, the present study aimed to address tokophobia (epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment) in fathers.

2. Evidence Acquisition

This comprehensive narrative review was conducted in three steps.

2.1. Identifying Research Question

This study aimed to answer the following research question: What are the epidemiology, etiology, clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of tokophobia in fathers?

2.2. Search Strategies for Identifying and Selecting Studies

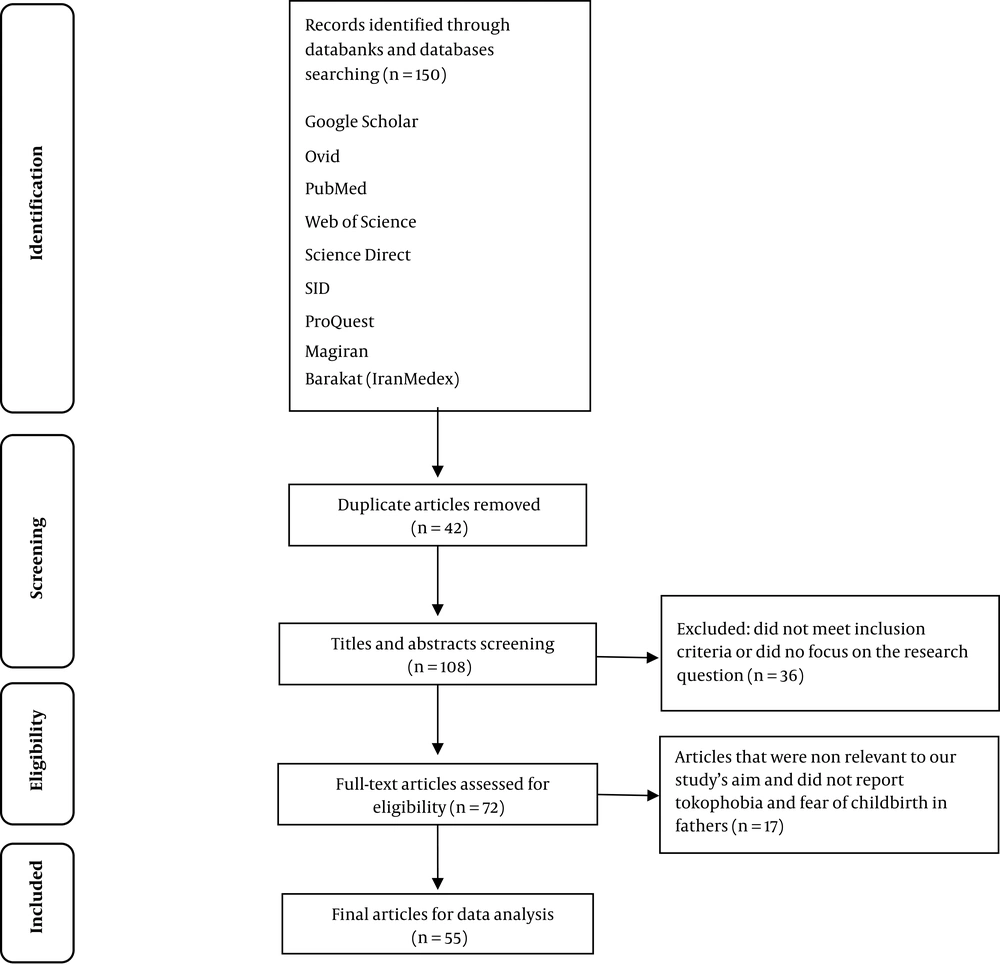

This was a review study in which the literature related to tokophobia and FOC was searched in databanks such as Ovid and Google Scholar, as well as other electronic databases including PubMed, ProQuest, Web of Science, Science Direct, Magiran, SID, and Barakat (IranMedex), without time limit. The search was performed in both “text word” and “Medical Subject Heading (MeSH)” strategies. For example, we used the AND/OR operators to do an advanced search for articles in the international PubMed database, as follows: "Pregnancy" AND ("childbirth" OR "parturition") AND ("tokophobia" OR "fear of childbirth") AND ("related factors" OR "influence factors" OR "contributed factors") AND "fathers" AND "health care providers" AND ("intervention" OR "methods") AND "impacts" AND "health" AND "prevalence". The related studies published from 1988 until 2020 were screened. Also, the reference lists of obtained articles were further screened for acquiring other related papers manually. Then, two authors independently screened the papers with the eligibility criteria. The eligibility criteria for the papers included publications in scientific and valid journals, in Persian and English languages, evaluating childbirth fear in fathers, its epidemiology, related factors, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis addressing the research question. Initially, 150 articles were recruited from the databases. Articles that did not focus on the research question of this study were excluded. Finally, 55 studies were used for reviewing after removing unrelated studies by reading their titles and abstracts (Figure 1).

2.3. Data Extraction and Reporting Data

The full text of each included article was read carefully and relevant information was extracted independently by the authors. A consensus was reached before the final inclusion of papers. Subsequently, the data obtained from the articles were placed into their respective categories.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

After removing unrelated studies, finally, 55 articles related to the purpose of the study were selected. The findings were reviewed for the epidemiology of tokophobia, as well as biopsychosocial etiology, clinical signs, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of tokophobia in fathers. The results of the studies are described in Table 1.

| Author, Year | Country | Type of Study | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency and Related Factors | |||

| Ganapathy et al. 2015 (3) | India | Cross-sectional | 78.4% of fathers suffered from tokophobia. The reported fears included fear related to the safety of the spouses and neonates, fear of delivery, professional competency, receiving inadequate care, and fear of responsibility. |

| Hildingsson et al. 2014 (19) | Sweden | Cohort | The frequency of FOC was 13.6%. The related factors were less positive feeling about approaching labor due, born in a country other than Sweden, preference of a cesarean section, and waiting for the birth of the first child. |

| Hildingsson et al. 2014 (20) | Sweden | Longitudinal regional survey | Expectant fathers with childbirth-related fear (13.6%) reported poorer physical and mental health than their non-fearful counterparts. |

| Schytt et al. 2014 (21) | Sweden | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | Mixed or negative feelings about the upcoming birth were more prevalent in men of advanced age (29%) than in men of average (26%) and young (18%) ages, and they feared the event more than the youngest (P < 0.01). |

| Johansson et al. 2012 (22) | Sweden | Qualitative-Quantitative | Fathers already having children had lower fear of childbirth than first-time fathers (repeat fathers 3.3%, first-time fathers 7.1%). |

| Eriksson et al. 2005 (23) | Sweden | Cross-sectional | Severe phobia was reported in 13% of men. The men with severe phobia were more frequently 40-years-old or higher. They also more commonly had more than 5 years’ interval between the birth of the first and the second children. |

| Szeverenyi et al. 1998 (24) | Hungary | Cross-sectional | More than 80% of men reported some degrees of FOC. Severe pain of partner, surgical aided delivery, delivery-associated fetus trauma, helplessness, and death of the spouse during pregnancy were important reasons for men’s phobia. |

| Vehviläinen-Julkunen et al. 1998 (25) | Finland | Cross-sectional | Only 3% reported that they were afraid their partner might die during delivery. The fears reported by men were related to the attitude of their spouse toward delivery, fear of the spouse’s death, and fear of surgical procedures. |

| Chalmers et a 1996 (26) | Africa | Cross-sectional | 13% of fathers had fears regarding under way childbirth. The main fears were related to fetus abnormalities, spouse’s pain, and fear of mortality of their partner and neonate. |

| Ayers et al. 2014 (27) | London | Editorial | The few research studies that have been carried out suggest that between 10% and 13% of men report intense FOC. |

| Eriksson et al. 2006 (28) | Sweden | Cross-sectional | The FOC in men were categorized in the delivery process, the health of the baby and mother, the partner’s capabilities, and the professionals’ competence and behavior. |

| Ledenfors et al. 2016 (29) | Sweden | Qualitative | Factors related to FOC included inadequate knowledge of pre-delivery events and how to manage labor pain by the mothers. |

| Greer et al. 2014 (17) | England | Qualitative | The most common men's fears included fear of incapability of providing adequate support during labor and harm to their partner or neonate in delivery. |

| Eriksson et al. 2007 (30) | Sweden | Qualitative | The primary reason for men’s phobia was related to the “health and safety of their partner and neonate”. |

| Saisto et al. 2001 (31) | Finland | Cross-sectional | FOC was related to some individual and socioeconomic characteristics (anxiety intensity, vulnerability, low self-esteem, unpleasant marriage, and absence of social support). |

| Boyce et al. 2007 (32) | Australia | Longitudinal | The poor knowledge of fathers regarding pregnancy and childbirth places them in distress. |

| Svensson et al. 2006 (33) | Australia | Longitudinal | Some fathers have had phobia regarding the influence of childbirth on their marital relationship. |

| Hanson et al. 2009 (34) | America | Review | Harm to mother or neonate, spouse’s pain, feeling of helplessness, inadequate knowledge, and fear of intervention were among major reasons for FOC in men. |

| Clinical Signs | |||

| Rondung et al. 2016 (35) | Sweden | Narrative review | The FOC is usually considered an anxiety disturbance clinically characterized by signs similar to emotional disorders (increased respiratory rate, vertigo, auto-negative impressions, and beliefs). |

| Saisto et al. 2003 (36) | Finland | Review | Childbirth presents as a phobic fear in the forms of nightmares, physical ailments, and difficulties in focusing on familial activities. |

| Eriksson et al. 2007 (30) | Sweden | Qualitative | The fear is often described as either “intellectual engagement”, “sleepiness”, or “physical complications” such as restlessness. |

| Treatment | |||

| Bergström et al. 2013 (37) | Sweden | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | Childbirth preparation including training as a coach may help them to have a more positive experience. |

| Wöckel et al. 2007 (38) | Germany | Prospective randomized design | The preparation classes together with partners have a positive effect on the experience of birth. |

| Premberg et al. 2006 (39) | Sweden | Qualitative phenomenological | The illustration can help fathers to accommodate with their experiences during childbirth. |

| Shirani et al. 2009 (40) | United Kingdom | Qualitative | Good information about pregnancy, birth, and beyond was seen as key for helping fathers to feel confident in their abilities. |

| Hildingsson et al. 2011 (41) | Sweden | Longitudinal | The support of midwives, for example, her/his presence in the labor room and giving imparting information, has been important. |

| Nystedt et al. 2018 (42) | Sweden | Cross-sectional | For psychological and non-pharmaceutical treatment, it is important to consider precedent experiences in these situations. |

| Hunter et al. 2011 (43) | United States | Mixed-method, experimental | One of the psychological treatments is the mantram. It has been associated with a significant anxiety reduction. |

| Buist et al. 2003 (18) | Australia | Longitudinal | Childbirth preparedness sessions should provide men with an opportunity to seek a specific role for themselves and their spouses. |

| Prognosis | |||

| Sapkota et al. 2012 (44) | Nepal | Qualitative with semi-structured interviews | Fathers’ fear may interfere with labor progression, particularly in cases of his inability to cope with the fear. |

| Philpott et al. 2017 (45) | Ireland | Systematic review | Fathers with positive feelings toward the approaching childbirth due have reported significantly lower fear levels than fathers with negative feelings. |

| Bergström et al. 2013 (37) | Sweden | RCT | Acute FOC in fathers also affects children’s attachment patterns, emotional, and cognitive development, and relationships between the father and his spouse. |

| Greer et al. 2014 (17) | England | Qualitative | In some men, FOC may lead to a feeling of distress and helplessness, and also, such men are more likely to prefer a cesarean section for delivery. |

3.2. Epidemiology of Tokophobia in Fathers

The frequency of FOC in fathers is unknown. A few studies on this issue have shown that 10-13% of men experience severe FOC (27, 37, 46). In a study on 1,047 fathers, Hildingsson et al. (2014) reported a 13.6% frequency for FOC (19). Evidence from studies on Indians shows that as high as 78.4% of first-time expectant fathers suffered from tokophobia. A recent descriptive study was conducted by interviewing 113 first-time fathers visiting prenatal clinics by using the Childbirth-Related Fear Questionnaire (CRFQ) (3).

In a study in Hungary on men’s experiences toward childbirth, 72-80% of them reported fear at some levels (24). A study in Finland also revealed sadness, fear, and impatience during childbirth in more than half of the respondents (25). In a study by Eriksson et al. in 2005 on 410 and 329 Swedish women and men, respectively, severe fear was reported in 23% of females and 13% of males. Among men with childbirth fear, 29% and 30% had moderate and mild levels of fear, respectively, while 28% declared no fear (23). Besides, 13% of fathers stated FOC in a study performed in South Africa (26). In another study by Bergstrom et al. in Sweden in 2013 on 762 men, 83 (10.9%) of the participants suffered from FOC, which was close to the ratio (13%) reported in similar studies (37). In a study in Africa toward the fathers’ experience about pregnancy and childbirth, 13% of the 46 participants stated fear (26).

In men who already had children and also experienced FOC, frequently more than five years elapsed from the first to the second childbirth (26). Fathers with previous children had a higher level of education and less FOC during pregnancy than first-time fathers (22). Adolescent fathers have been reported to have poorer coping skills during labor and a higher perinatal depression rate than older fathers (4).

3.3. Biopsychosocial Etiology of Tokophobia

3.3.1. Biological Factors

Tokophobia is a relatively unknown anxiety disorder (15, 47). Anxiety disorders can be classified as either panic, specific phobia, or social phobia. An aspect of anxiety disorders is the exquisite interplay of genetic and experiential factors. Biological factors such as the autonomic nervous system are also involved in this disorder. Based on studies and therapeutic responses, norepinephrine (NE), serotonin, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) have been described as the main neurotransmitters associated with anxiety. Heredity has been recognized as a predisposing factor in the development of anxiety disorders. Approximately half of the patients affected with panic have had at least one affected individual in their relatives.

Genetic factors can contribute to specific phobia; indeed, the phobia is an interaction between genetic and environmental stress factors. Longitudinal studies suggest that certain persons are constitutionally predisposed to phobias because they are born with a specific temperament (48). Different hypotheses have been suggested for explaining FOC, including a disturbance in neural-hormonal homeostasis (i.e., disturbed anxiety-regulating mechanisms) (5).

3.3.2. Psychological Factors

The birth of a child is one of the most important interpersonal transitions for couples (36). The feeling of insecurity and anxiety can be related to the relatively unknown, uncontrollable, or inevitable nature of childbirth. From a psychological point of view, this situation may be very distressing for some individuals (49).

The men's phobia may also be related to the concerns regarding the "health and safety of their partner and child” (21, 30). Fathers have stated that there may be events during childbirth leading to serious trauma or even the death of their spouse or child (17, 34, 43). These have been the most important reasons for phobia reported by fathers (25, 34). Another major reason for phobia reported by fathers has been concerns regarding abnormality and neonatal developmental defects (26, 28). Furthermore, some men stated their spouse’s phobia as the reason for their fear, indicating that mothers’ fear can lead to childbirth fear in fathers (30).

Of the psychological factors predisposing to tokophobia is an individual tendency to anxiety and depression (10, 16), low self-esteem (31), mood disorders, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), history of psychological diseases, personality disorders (35), and fear of parental duties (50). The sadness feeling, unresolved distress, and insecurity in fathers have been related to higher anxiety, phobia, and irritability levels. Fathers with positive feelings toward the approaching childbirth due have reported significantly lower fear levels than fathers with negative feelings (19, 45). Factors such as lack of self-confidence, low self-efficacy, and self-deprecation are predictors of severe phobia (23).

Other individual psychological factors related to FOC have been comprehending childbirth as a dangerous event (51), being under pressure to attend childbirth (52), negative view toward pregnancy and childbirth (53), unpleasant experience from previous childbirth (1, 42), disappointment, distrust, and fearing of helplessness in case of needing (11), first paternal experience (25), helplessness (24, 54), fear of losing closeness and marital intimacy (34), fear of failure in being a good father (26, 34), and fear of inability to fulfill the spouse’s needs (4, 20). The other reasons for fears associated with childbirth have been concerns regarding the capabilities of the spouse to cope with the pain (3, 21, 29), fear of failure in calming down the partner during labor and childbirth (38, 44), and fear of not being at the hospital in time (26).

Some fathers have been concerned about the type of childbirth and considered the vaginal method as a dangerous route with the possibility of disproportioned neonates’ body and vaginal space (17). Also, some fathers have had phobia regarding the safety and sexual health following episiotomy (34) and the influence of childbirth on their marital relationship (33). A lower number of fathers had fears that their child might be mixed up with someone else’s child (34). The other factors related to FOC can be poor health self-reporting during pregnancy (27, 51). there were no differences in fear scores related to the planned or unplanned pregnancy or in the situations of the pregnancy being preceded by a period of infertility or assisted gestation (19).

3.3.3. Social Factors

To a large extent, fathers’ phobia has been related to being expatriate. Studies have shown that this can lead to poor communication between fathers and health providers and increase their fear (19). The communication problem is a key concern in fathers with FOC (23). Migrants can be more influenced due to being unfamiliar with the routine procedures and hospital environment (19). The poor knowledge of fathers regarding pregnancy and childbirth places them in distress (19, 32). This necessitates providing appropriate information for fathers regarding pregnancy and childbirth (32). On the other hand, fathers need more support from physicians and obstetricians (44). One of the suitable strategies is to attend antenatal classes. However, some studies have noted that fearful fathers less frequently participated in such sessions than did fearless fathers (20, 27). Avoiding from receiving the information may be a preferred approach in phobic fathers for controlling their fear and anxiety (20). On the other hand, some fathers have doubted the usefulness of antenatal classes and even stated that these sessions boosted their fears on some occasions (34).

Cultural differences may contribute to the FOC in fathers. Of these, one can note the medicalization of childbirth and preferring cesarean section (C/S) (54). Some fathers believe that childbirth is a dangerous situation needing to be replaced by C/S considering available medical care (23). In the study by Hildingsson (2014) et al., half of the fathers with fear had been born in countries in which cesarean prevailed (19). Studies have also shown the importance of information acquired by the family and friends in childbirth-related phobia (35). Describing negative and fearful experiences and stories has been one of the most important contributors (1, 35, 54). Accordingly, media and school-based educations also impact the attitude toward pregnancy (35). Regarding the negative impacts of media, studies have shown that most women and their partners have used the internet as the sole source of information in pregnancy. The information source may be either poor or misleading. In the case of childbirth demonstrations, they can increase the childbirth phobia if being watched without previous knowledge. Those relying on the media as the sole information resource have stated the highest rate of childbirth-related phobia and preferred a cesarean section as twice as those utilized different information sources (15).

Fathers have declared some other factors contributing to FOC, such as the incompetence and misbehavior of health care personnel and midwives (3, 30), fears related to not being treated with respect and not receiving sufficient medical care (3, 28), distrust in the personnel (54), inadequate support during childbirth (11, 28), and fear of being left outside making important decisions (4, 23). These findings indicate that some fear-inducing factors are originated from the healthcare system (28). The hospital may be a very upsetting and fearful environment for many individuals, and this may promote phobia in fathers (34).

3.4. Clinical Signs

The activation of the autonomic nervous system leads to specific signs, including cardiovascular (tachycardia), muscular (headache), gastrointestinal (diarrhea), and respiratory (tachypnea) signs. The autonomic nervous system has been responsible for an increased sympathetic tune, slow adaptation to incessant stimuli, and excessive response to intermediate stimuli in some patients with an anxiety disorder (48).

The FOC is usually considered as an anxiety disturbance clinically characterized by signs similar to emotional disorders. Anxiety disorders are usually characterized by an increased respiratory rate, vertigo, auto-negative impressions, and beliefs (35). This can also be associated with an unpleasant and fearful feeling accompanying by headache, sweating, dyspnea, chest pain, and mild gastric disorder presenting with the inability to long sit or long stand situations (48).

Overall, childbirth presents as a phobic fear in the forms of nightmares, physical ailments, and difficulties in focusing on familial activities (36, 51). The fear is often described as either “intellectual engagement”, “sleepiness”, or “physical complications” such as restlessness (30). A fearful person tries to avoid phobic stimuli. In the psychological evaluation of patients with the phobia, depression is usually observed as a co-existent condition (48).

3.5. Tokophobia Diagnosis

Most fathers do not speak of their FOC to their friends, relatives, or even their partners and try to hide their feelings and concerns (30, 34). The main reason for this has been avoiding making their spouses concerned, believing that talking about the fear may transfer this feeling to the mothers (30). Therefore, they prefer not to disclose their feelings despite great concerns. Furthermore, some have declared social-cultural factors as the reason for hiding their feelings (4). Sexual preferences and social conventions regarding men’s attitude may lead some fathers to believe that a man’s fear is acceptable for nobody (30). It seems that the knowledge of health care providers of this issue (i.e., fathers hiding their fear of childbirth) can be essential. Therefore, seeking anxiety and fear in fathers is of critical importance while providing health care services (23). Continuous midwifery services can seed trust (1). Also, the participation of fathers in prenatal communications with health providers about their experiences and feelings regarding pregnancy and childbirth can provide an opportunity for scrutinizing childbirth-related phobia (20, 30).

The FOC in fathers can be evaluated and diagnosed through either conversation, interviews, or questionnaires (23). After identifying phobic fathers, meetings should be arranged between them and health care providers, giving the fathers a space to divulge their fears and seeking ways to cope with the situation (20, 30). The knowledge of diagnostic criteria of specific phobia can assist in the diagnosis of this disorder. The diagnosis of specific phobia is warranted in situations with great anxiety levels mimicking panic. The fear, anxiety, and avoidance are long-lasting (usually six months or more). Furthermore, such fear and anxiety may lead to remarkable clinical distress or disturbances in social, occupational, and other important situations (48).

3.6. Treatment

3.6.1. Psychological and Non-pharmaceutical Treatment

Tokophobia treatment should be directed toward decreasing anxiety and supporting fathers by providing adequate information, as well as educating, explaining, and managing the possible alternations and complications of pregnancy and childbirth (3). Fathers consider health care experts as their primary information source seeking their support and assurance (34). The health care providers should exude appropriate information in suitable times to avert the fear and anxiety (29), which makes this strategy (i.e., continuous and secure informing by health experts) the most reliable and best way to cope with such fears (17). The support from midwives, for example, their presence in the labor room and imparting information about the labor progress, is important. This is important for prenatal education of couples and health experts (41). Health care providers can educate relaxation to fathers that is useful for reducing anxiety (3, 55).

Childbirth preparedness sessions should provide men with an opportunity to seek a specific and assisting role for themselves and their spouses (18, 38). Some men may feel shame to participate and share an innermost feeling with others. Studies have revealed that this may be easier when the participating fathers have similar educations (40). Adolescent fathers have weaker coping capabilities in expose to labor and are more susceptible to perinatal depression than older fathers, necessitating to provide them with more personal counseling services and educational information. Coping strategies for fathers include social support, cognitive reframing, dissociating their distress from their spouses, taking responsibility for their feelings, and empathetic detachment (4). One of the coping strategies against fathers’ fear has been trying to boost the feeling of under controlled situation. Some fathers have declared that they constantly try to be prepared to deal with possible events and how to react during childbirth. Some men, on the other hand, have had themselves busy with other activities to overcome their fear (30).

The illustration can help fathers to accommodate their experiences during labor and childbirth and prepare for difficult and unpredicted situations. Sharing experiences and group speaking with other men, in the absence of women, has been essential. Men have asserted the effectiveness of men-oriented discussions (39).

Being prepared for childbirth as a coach may contribute to a positive feeling about the event in phobic men. Fathers with FOC undergoing intervention with psych prophylaxis have had a higher preparedness rate for the event (37). Cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychotherapy (to manage emotions) have had promising results (5). The cognitive approach to treat FOC is particularly suitable due to being short-term, dynamic, and focused on one problem (36). Different psychotherapy interventions can be effective and delivered by simple or individualized psychoeducation (36). Other therapeutic methods comprise self-hypnotism and mind-oriented treatments. Constant support and individual screening are also effective in tokophobia treatment (15).

One of the methods of uncertainty is the mantram. It is the mute repetition of a sacred word or phrase chosen by a person himself to be guided to the attention and calm. Studies have shown that the has been associated with a significant reduction in perceived stress, anxiety, anger, and post-trauma stress, as well as improvement of quality of life and spiritual health (43).

3.6.2. Pharmaceutical Treatment

In the case of childbirth, pharmacotherapy can be used to treat anxiety, depression, or serious psychological disorders (5). Beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists may be beneficial in the treatment of specific phobia. Due to the intrinsic long-lasting feature of phobia, a therapeutic pattern should be planned. The four major drugs to be considered for the treatment of anxiety disorder are benzodiazepines, SSRIs, buspirone, and venlafaxine.). Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), or paroxetine (Paxil) are better choices for patients with severe anxiety disorders. Other potentially useful drugs may be tricyclics (e.g., imipramine), antihistamines, and beta-adrenergic antagonists (e.g., propranolol) (48).

Reviewing studies indicates that there are few methods for alleviating FOC in men (51) with no census on the methodology, timing, and the person in charge of performing potential interventions (2). Therefore, more evaluations are required for developing and identifying effective methods for reducing childbirth phobia in men (51).

3.7. Prognosis

Acute FOC and psychological distress in fathers can affect children’s attachment patterns, emotional and cognitive development, and relationships between the father and his spouse (37). Also, childbirth-related fear can affect the ability of fathers to emotionally and physically support their partners (3, 37), as well as their capability to achieve their paternal roles, thereby largely pressuring them (3, 34).

In some men, FOC may lead to a feeling of distress and helplessness (17). Evidence indicates that fathers’ stress and fear may interfere with labor progression, particularly in cases of their inability to cope with the fear (44). Studies also revealed that fathers with a childbirth-related phobia would less likely consider the pregnancy as a positive event in life (19), and also are more likely to prefer a cesarean section for delivery (17, 19).

Our review indicated that stress can negatively affect the fathers’ psychological and physical health, as well as their social relationships. Also, fathers’ anxiety during the prenatal period negatively influenced marital satisfaction (45). There were also positive correlations between childbirth-related phobia and fatigue, sleepiness, and anxiety (50). Furthermore, FOC in men exerts some complications in future deliveries (37). The knowledge regarding individual and social outcomes of childbirth-related fear is rare in both men and women (23).

One of the limitations of the present study was that the authors only reviewed English and Persian articles, and quality appraisal of the articles was not done.

The participation of fathers in the process of pregnancy and childbirth is important. The fear of childbirth and related psychological conditions, even in fathers, can be important in choosing the method of childbirth and may affect their mental health. However, studies have less considered this disorder in fathers. The results of the present study can assist the health care team in identifying and screening fathers at risk of tokophobia and performing the necessary interventions as a guide. The results of this research can also be used in future research.

4. Conclusions

Tokophobia, as a psychological disorder in which multiple factors can contribute to pathogenesis, ought to be brought into focus as a general health issue. Detecting FOC in fathers and applying therapeutic interventions concentrated on the fathers’ needs can be effective in the fathers’ health and also on their support of the mothers and interactions with children. Fathers may not express their fears, and thus, health care providers should particularly consider this and apply some interventions to alleviate this disorder. As there are a few studies addressing tokophobia in fathers, its outcomes, and possible effective interventions, more studies are needed in this field.