1. Background

Adolescence is a period of physical, social, and mood change, as well as autonomy and responsibility regarding health, family, job, and peers (1). In this period, adolescents accept new roles and responsibilities and learn the necessary social skills to take on those roles (2). Nevertheless, adolescence can also be a critical period in one’s life, as important behavioral patterns that affect one’s entire life are formed during this period. In this regard, Juan-Pablo and Stefan argue that in this period, teenagers try to establish their positions amongst family members, friends, and society, which eventually forces them to choose high-risk behaviors in the decision-making process (3).

Risky behaviors are potentially destructive, either deliberately committed by an individual or unintentionally, either committed by an individual deliberately or without knowing the adverse individual and social consequences endangering their health and well-being (4, 5). High-risk behaviors are particularly common during adolescence (6), in a way that they take part in these types of activities as they grow up, and their willingness to consistently conduct such behaviors increases. In this regard, Kloep et al. (7) believe that the most important risky behaviors are substance abuse, unprotected sexual activity, fighting, and violence. However, Boyer considered alcohol and tobacco abuse, unprotected sexual activity, reckless driving, and interpersonal violence as the most important ones (4). Research conducted by Zadehmohammadi and Ahmadabadi (8) also indicated that high-risk behaviors amongst Iranian adolescents include violence, suicide, reckless driving, smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, and high-risk sexual behaviors.

In spite of ever-increasing efforts to prevent and control high-risk behaviors, its related data amongst adolescence is still alarming (9). In this regard, research conducted by Grarmaroudi et al. (10) showed that 8.7% reported smoking, 7.4% alcohol consumption, 2.7% narcotics consumption, and 20.2% sexual activity. Extensive prevalence of high-risk behaviors and its relationship with suicide, early mortality, heart diseases (11), psychiatric disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts (12), and drug addiction, AIDS, and STDs (13) has doubled the importance and necessity to examine the culprit factors and ways to predict them.

In the conducted research, the role of various psychosocial factors in the incidence of high-risk behaviors has been considered, amongst which are the parental monitoring and conflict in the family (14) and high level of thrill-seeking and low self-esteem (15). Within the last decade, motivations for high-risk behaviors are among the factors that have drawn the attention of researchers.

Motivation is a general term that defines the common ground between needs, cognitions, and emotions; each of these inner processes strengthens and guides the behavior. The process of motivation consists of complex forces, drives, needs, stressful situations, or other mechanisms, which are initiated and maintained in pursuing a goal. In other words, motivation is the desire to perform activities necessary to achieve the goals (16). Motivation consists of three main elements: (A) Activating forces: forces in individuals that cause each person to behave in a specific way; (B) guiding forces: directing behavior toward things; that is, they are purposeful; and (C) sustaining forces: which sustain and guide human behavior toward achieving the goal (17).

Individuals’ behaviors in different areas are influenced by their motivations, and one of them is psychological motivation (17, 18). According to Reyna and Farley (19), seemingly illogical behaviors can be logical once the goals and motivations of the decision-maker are considered. Awareness of people’s motivations for committing high-risk behaviors helps to explain the underlying causes and provides a framework for their use in preventive and therapeutic interventions. Effective motivations for the occurrence of high-risk behaviors were investigated in several studies (7). There are various motivations for showing high-risk behaviors in the literature related to these behaviors; among them are thrill-seeking, calculation, audience control, hedonistic, and irresponsibility (20).

Regarding the importance of prevention and management of high-risk behaviors in the individual and social life of adolescents, investigation in this field is crucial and practical. Previous studies have been carried out merely on drug abuse or female adolescents. In other words, no study was found that examined the psychological motivations for high-risk behaviors in Iranian male adolescents.

2. Objectives

Hence, the present study was conducted to evaluate the predictive model of high-risk behaviors in adolescents based on their motivations.

3. Methods

The study has a correlational design and uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to examine the relationships between research variables in the form of a model. The statistical population of the study consisted of all high-school students in Shiraz. According to Krejcie and Morgan’s (21) table and the population size (n > 100000), the minimum sample size was calculated as 384. However, considering the probability of sample drop-out, 450 participants were selected through a convenience sampling method, and 412 participants completed the paper-based questionnaires. The following instruments were applied to collect data.

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Iranian Adolescents Risk-taking Scale (IARS)

This scale consists of 38 items for assessing vulnerability to high-risk behaviors such as violence, drug abuse, alcohol consumption, and sexual behavior. The possible responses were from “totally disagree (1)” to “completely agree (5)”. Using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, the reliability of Iranian Adolescents Risk-taking scale (IARS) was reported as 0.93 for the overall scale, 0.93 for the drug abuse subscale, 0.74 for the risky driving subscale, 0.78 for the violence subscale, 0.93 for the smoking subscale, 0.90 for the alcohol consumption subscale, and 0.87 for the sexual relationship subscale (8). In this study, Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.67.

3.1.2. Motives for Risk-taking Scale (MRS)

It was used to assess the motivations for high-risk behaviors. Kloep et al. (7) designed this scale. This self-reporting instrument is a 25-item scale for measuring an individual’s psychological motivations for committing high-risk behaviors. Scoring this scale is based on the responses by individuals on a Likert scale (from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”) (7). Hosseini and Aminimanesh (22) have reported the psychometric properties of the Persian translation of this scale as acceptable. In this study, the reliability of the subscales of thrill-seeking, calculation, audience control, hedonistic, and irresponsibility was calculated by Cronbach’s alpha as 0.84, 0.78, 0.84, 0.85, and 0.76, respectively.

3.2. Data Collection

With permission from the Education Department of Shiraz, four schools were selected, and the survey was conducted. The inclusion criteria were age from 14 to 18 and willingness to participate in research. The participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and they could leave the study at any time. To enhance confidentiality, all questionnaires were completed anonymously, and only required information was collected. All participants were informed about the goals of the survey and completed paper-based questionnaires with regular supervision to provide reliable and valid data. Also, participants signed the informed consent form, and completed the questionnaires individually in the presence of the researchers at school. In addition, ethical approval with the code IR.IAU.SHIRAZ.REC.1398.004 was obtained.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

To test the research model, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used along with the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method. Also, to investigate the fit of the research model with data, chi-square, chi-square/degree of freedom, the goodness of fit index (GFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), normed fit index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square of residual (SRMR) were used. For data analysis, AMOS V22.0 was used.

4. Results

The participant’s mean and standard deviation (SD) of age was 16.17 and 0.78 years, respectively. All participants were male high school students. Besides, 37.43% and 25.52 % of the students’ fathers and mothers had an associate’s degree or higher, respectively. The descriptive statistics related to the variables of the present model, including the mean and standard deviation, along with a bivariate correlation matrix for the variables, are shown in Table 1.

| Model Variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Independent variables | ||||||

| 1. Thrill-seeking | 1 | |||||

| 2. Calculation | -0.78** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Audience control | 0.56** | 0.57** | 1 | |||

| 4. Hedonistic | 0.67** | 0.71** | 0.56** | 1 | ||

| 5. Irresponsibility | 0.50** | 0.54** | 0.45** | 0.59** | 1 | |

| Dependent variable | ||||||

| 6. High-risk behaviors | 0.54** | 0.45** | 0.37** | 0.51** | 0.46** | 1 |

| Mean ± SD | 12.31 ± 4.40 | 12.92 ± 4.19 | 15.85 ± 5.63 | 15.26 ± 5.42 | 14.16 ± 5.06 | 67.41 ± 21.22 |

a*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Table 1 shows that all predictor variables of the model had a significant relationship with high-risk behaviors. The research model consisted of six variables, including five motivations for high-risk behaviors, which are considered exogenous variables, and the latent variable of high-risk behaviors as an endogenous variable. The model was analyzed using the maximum likelihood estimation method and the fit indices were extracted. This model was found to fit the observed data adequately: χ2/df = 2.89 (< 3), GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.92, NFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95, CFI = 0.97 (all > 0.90), RMSEA = 0.066 (< 0.08), and SRMR = 0.043 (< 0.06). These results show that the fit indices of the model lied within the desirable range; hence, this model fitted the data extracted from the sample group.

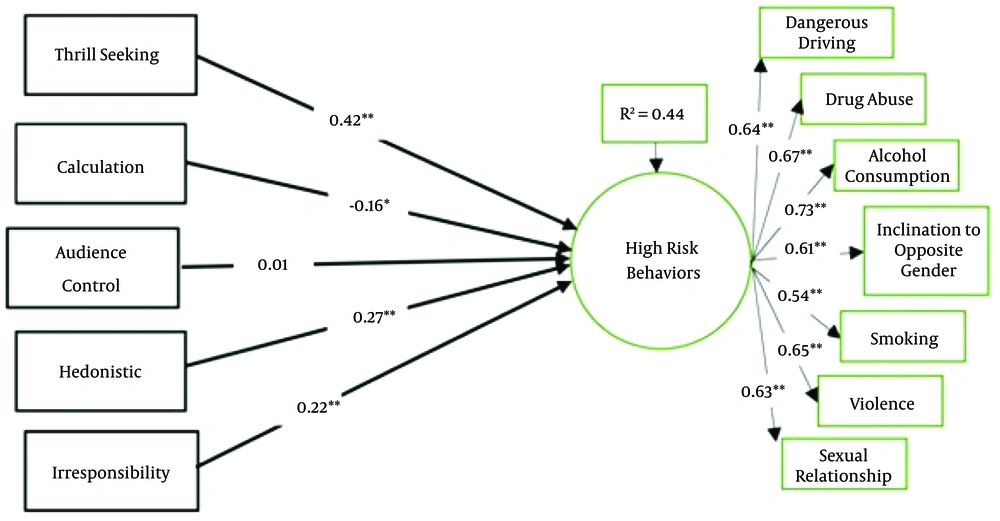

Figure 1 shows the estimated parameters for the predictive model of research using the maximum likelihood method. The standardized path coefficients, the significance of these coefficients, and the factor loadings on the latent variable of high-risk behaviors are presented in Figure 1.

The results shown in Figure 1 suggest that amongst motivations for high-risk behaviors, hedonistic, thrill-seeking, and irresponsibility with a positive path coefficient and calculation with a negative path coefficient could significantly contribute to the prediction of high-risk behaviors. Also, the factor loading of high-risk behaviors on the latent variable showed that motivations had the strongest impact on alcohol consumption and the minimum impact on smoking. Finally, these results indicate that the motivations for high-risk behaviors were generally able to explain 44% of the variance.

5. Discussion

The goal of this research was to assess the predictive model of high-risk behaviors amongst Iranian male adolescents based on motivations. The results of this study showed that among motivations of high-risk behaviors, thrill-seeking, irresponsibility, calculation, and hedonistic could significantly contribute to the predictive model. The results are in line with the findings of Sehat and Aminimanesh (23), Tao et al. (24), Thornberry et al. (25), Draucker and Mazurczyk (26), and Johnson et al. (27).

The role of thrill-seeking in the incidence of high-risk behaviors was reported in numerous studies (28). Thrill-seeking refers to a person’s desire to experience intense and novel pleasures, regardless of possible dangers and long-term consequences (29). Explaining the role of thrill-seeking in predicting high-risk behaviors, one can argue that thrill-seeking individuals have a strong desire to experience new situations and conditions, which gradually makes them unsympathetic and careless regarding the risk factors, which leads to high-risk behaviors (30, 31). Moreover, due to their stronger behavior-activating systems, these individuals require stronger brain stimulation and have a great tendency to participate in curious behaviors compared to those with a weaker desire for excitement (32). Research findings suggest that risk perception can play a mediating role in the relationship between sensation seeking and high-risk behaviors. This means that based on their perception of the risk and the degree of sensation involved, individuals decide on whether or not they should take on these behaviors (30, 33). Lajunen found that thrill-seeking was also a predictive factor for violence. Moreover, there is ample evidence that thrill-seeking individuals are risk-takers while people with a low level of thrill-seeking avoid risky activities (30, 34).

In explaining the role of irresponsibility in predicting high-risk behaviors, it can be said that irresponsible individuals are usually unrestrained, neglect their duties, and do not care what others think about their behaviors, all of which make them more willing to participate in high-risk behaviors (35). According to the literature, irresponsibility is associated with a lack of regard for legal constraints and serious consequences for social and organizational status. By the same token, adolescents with a lower sense of responsibility pay little attention to the long-term consequences of their behaviors, and for this reason, they become more vulnerable to the immediate gratification of high-risk behaviors (7).

Hedonistic and audience control motivations might pave the way for people to enter into new relationships and environments that can expose them to high-risk behaviors. It can also affect a person’s behavior via increased peer pressure (36). Calculated risk motives are also worthy of discussion. As expected, this motivation was negatively associated with risky behaviors. In such cases, interventions should focus on motivations rather than behaviors. On the other hand, certain behaviors might seem to be extremely risky, although the underlying motives are potentially favorable for development. For instance, a young person wanting to embark on a sports career might choose to take ‘calculated risks’, but overestimate their benefits and actually engages in highly dangerous risk-taking. In this case, abilities such as risk assessment should be trained (7).

The limitations of this study are worthy of discussion. Despite the efforts made to expand the sample distribution by selecting different districts of Shiraz, our method could not be regarded as random sampling, and this issue should be considered in the generalization of the findings. Another limitation of this study is that the measurement of research variables was based on participants’ self-report, and there was no independent method for testing the validity of their responses. Future studies would probably benefit from using interviews and observational research data to help researchers understand the connections of adolescent high-risk behaviors and their psychological antecedents in greater depth. Finally, since this research was conducted only on male adolescents, it is suggested that the role of age and gender be also investigated in future studies.

5.1. Conclusions

Considering the role of motivations in doing high-risk behaviors, more attention should be given to thrill-seeking, irresponsibility, calculation, and hedonistic motivations in preventive and therapeutic interventions.