1. Context

Advancements in medical disease treatment and control of fertility rate during recent decades have been led to a continuously increasing number of older adults (1). World health organization introduced the chronological age 60 and over for less developed and the age 65 and over for developed countries, as the onset of late life (2). Depression is a major health problem in late life. It is defined as a clinical entity, presented by pervasive feeling of sadness at least for 2 weeks and some additional symptoms such as feelings of guilt or worthlessness, difficulty with concentration, feeling restless or fidgety, sleep difficulties, change in appetite, and/or loss of interest in people and activities (3). Depression is as prevalent in the aged and even more, compared to other age groups, and has a lot of devastating consequences, too. It may lead to increased rates of morbidity and mortality, impaired quality of life and functioning as well as delayed improvement of concomitant medical conditions (4).

The prevalence of major depression in community dwelling older adults was reportedly about 1% - 4%, but some believe that mild depressive symptoms and sub threshold depression are more prevalent in older adults. However, symptoms of depression often fail to meet the diagnostic criteria, so they usually are not considered as clinical (5). The reported prevalence of geriatric depression was variable; from 19.5% in western countries (6), 27.8% in Sri Lanka (7) to 23% in Pakistan (8), 58% in Iran (9) and 20% - 34% in South Korea (10).

Although diagnosis and treatment of geriatric depression are very important concerns, they may not be adequate to resolve its impact because depression can become considerably burdensome even after treatment. Some symptoms of depression are not relieved by treatment and geriatric depression has some adverse effects such as impaired cognitive and social functioning that may remain indefinitely (11). These consequences can be avoided by making prevention of depression a top priority. Therefore, recognition of risk factors and factors that protect against depression in later life is necessary for health policymakers and care providers. Many studies have investigated risk factors of geriatric depression and some factors and biological mechanisms have already been identified (12-14). Some believe that late life depression mainly affects older people with chronic diseases, disability and loss. They have also stated that there is a wide spectrum of psychosocial factors that can empower older adults against stressful life events and prevent depression (15). Social network support and spirituality are two of the most effective modifiers that are worth mentioning (13, 16). International reports present a wider range of protective factors. In this study, a systematic search was done to identify recent findings through a review of the literature on protective psychosocial factors of depression in community dwelling older adults. It is believed that promoting knowledge of health care providers about these factors can be effective in helping to prevent later life depression.

2. Evidence Acquisition

This review was done as part of a more comprehensive one with the aim of recognizing the psychosocial factors associated with late life depression in community dwelling older adults. We collected the data through an extensive search in the reliable scientific data bases and analyzed the results in a narrative review format.

2.1. Search Strategy

A systematic search was done on Pubmed and Science direct WebPages from 2002 to 2016 using the key words: (depression OR “depressive disorder”) AND (geriatric OR elderly OR “late-life” OR “old age”) AND (“associated factor” OR “related factor” OR “predict*”). These key words were searched in titles and abstracts of articles.

2.2. Selection Criteria

Inclusion criteria were; original articles, those written in English and articles that investigated psychosocial factors associated with late life depression in community dwelling older adults. Exclusion criteria were; articles on hospitalized and institutionalized older people, those on biological mechanisms of depressive disorder, and those on treatment of depression and articles that involved depression related to special diseases.

2.3. Analyzing the Data

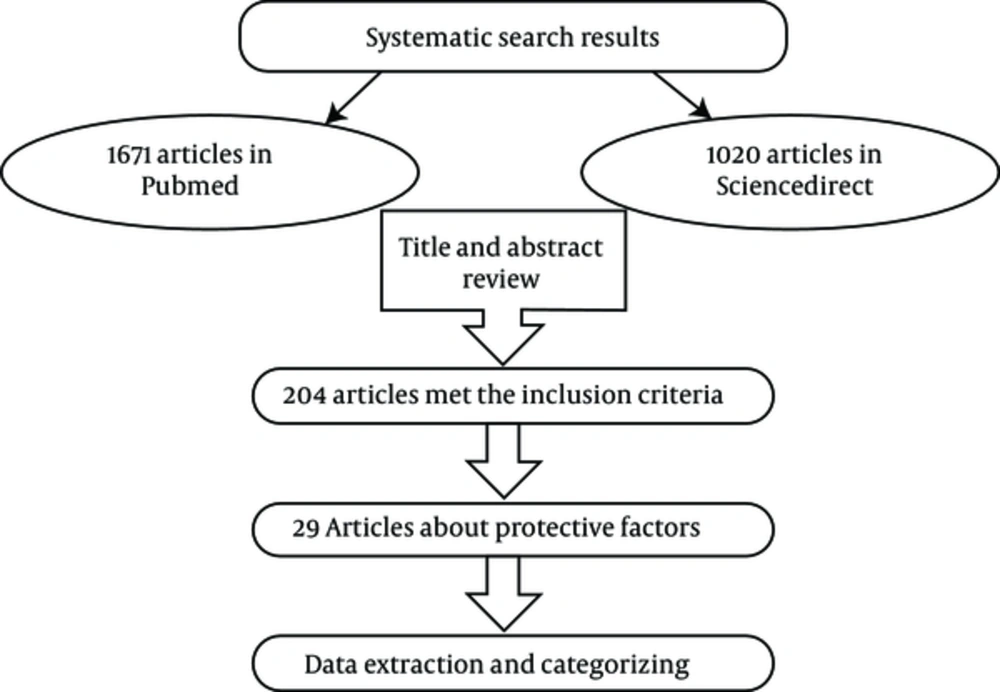

First, two members of the research team reviewed the titles and abstracts to identify relevant factors in the qualified studies based on the inclusion criteria. In case of disagreement between them, we used another researcher’s opinion. Then full texts of the selected articles were reviewed and the associated protective psychosocial factors were extracted by two researchers. In the next step, all the extracted factors were categorized and re-categorized during several meetings of team members to produce an agreed version of the geriatric depression psychosocial protective factor categorization. Summary of method is shown in Figure 1.

3. Results

Our first search results contained 1,671 and 1,020 articles in Pubmed and Science direct websites respectively. There were 204 articles remaining after titles and abstracts had been revised for relatedness and repeated articles had been withdrawn.

Among these, 29 studies were about protective psychosocial factors or modifiers of later life depression (Table 1). Thus 29 articles were analyzed, including 20 cross sectional and 9 longitudinal studies.

| No | Author | Study Design | Sample Size | Age | Depression Scale | Year | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jang Y. | Cross sec. | 406 | > 60 | GDS1 | 2002 | USA |

| 2 | Chou K.L | Cross sec. | 2003 | > 60 | GDS | 2006 | Hong Kong |

| 3 | Cheng S.T | Cross sec. | 205 | > 60 | CES-D2 | 2008 | Hong Kong |

| 4 | Choi N.G | Cross sec. | 213 | 58 - 95 | GDS | 2008 | USA |

| 5 | Kim J.I | Cross sec. | 295 | > 65 | GDS | 2009 | S. Korea |

| 6 | Okamoto K. | Cross sec. | 754 | > 65 | CES-D | 2010 | Japan |

| 7 | Jogerst G.J | Cross sec. | 1115 | > 60 | PHQ3 | 2011 | International (Korea, USA, Russia) |

| 8 | Li N. | Cross sec. | 460 | > 60 | GDS | 2011 | China |

| 9 | Chiao C.Y | Cross sec. | 116 | > 65 | GDS | 2011 | Taiwan |

| 10 | Rosmarin D.H | Cross sec. | 34 | > 55 | MADRS4 GDS | 2011 | USA |

| 11 | Olutoki M.O | Cross sec. | 350 | > 60 | GDS | 2012 | Nigeria |

| 12 | Chang C | Cross sec. | 427 | > 65 | GDS | 2012 | Taiwan |

| 13 | Kim B.J | Cross sec. | 210 | > 65 | GDS | 2012 | USA( Korean immigrants) |

| 14 | Lloyd S.J | Cross sec. | 128 | > 65 | GDS | 2012 | USA |

| 15 | Bozo O. | Cross sec. | 102 | > 60 | Beck | 2014 | Turkey |

| 16 | Jameson K | Cross sec. | 105 | Average 74.24 | HRSD5 | 2013 | USA |

| 17 | Guo. M. | Cross sec. | 1224 | > 60 | CES-D | 2014 | China |

| 18 | Fastame M.C | Cross sec. | 149 | > 65 | CES-D | 2015 | Italy |

| 19 | Bhamani M.A | Cross sec. | 953 | > 60 | GDS | 2015 | Pakistan |

| 20 | Aflakseir A.A | Cross sec. | 108 | > 55 | GDS | 2016 | Iran |

| 21 | Pitkala K.H. | longitudinal | 491 | 75/80/85 | Zung DS6(DSM-III) | 2004 | Finland |

| 22 | Mancini A.D | longitudinal | 1532 | > 65 | CEDS | 2006 | USA |

| 23 | Bots S | longitudinal | 526 | 70 - 84 | Zung SRDS | 2007 | Europe (Finland, Italy, Netherland) |

| 24 | Ahern M.M | longitudinal | 102 | 64 - 66 | CES-D | 2008 | USA |

| 25 | Turvey C.L | longitudinal | 5289 | > 70 | CESD-8/CIDI-S | 2009 | USA |

| 26 | Tsai A.C | longitudinal | 1609 | > 65 | CES-D | 2011 | Taiwan |

| 27 | Sun F | longitudinal | 1000 | > 65 | GDS | 2011 | USA |

| 28 | Chao S.F | longitudinal | 4049 | > 60 | CES-D | 2011 | Taiwan |

| 29 | Santini Z.I | longitudinal | 6105 | > 50 | CES-D | 2016 | Ireland |

a1- geriatric depression scale; 2- center for epidemiologic studies depression rating scale; 3-patient health questionnaire; 4-Montgomery and Asberg depression rating scale; 5- Hamilton rating scale for depression; 6- Zung self rating depression scale.

Categorization of the extracted data identified five main categories including demographic factors, social factors, physical health related factors, psychological factors and spiritual factors which are shown in Table 2. Those in bold in Table 2 are the psychosocial protective factors derived from longitudinal studies and are more strongly evidence based.

| Category | Protective Factors |

|---|---|

| Demographic factors | Being married |

| Living with others such as spouse, child, etc | |

| Older age | |

| higher education | |

| Better Socioeconomic status/ higher income | |

| Psychological factors | Higher level of environmental mastery |

| Greater emotional intelligence | |

| Preservation of cognitive function | |

| Downward social comparison | |

| Greater optimism and less pessimism | |

| Positive life orientation including being satisfied with life, having zest for life, havingplans for future, | |

| feeling needed, rarely feeling lonely or depressed Internal health locus of control | |

| Social factors | Pride in long and strong marriage |

| Marital closeness | |

| Having multiple children | |

| Social network support and satisfaction with it | |

| Community participation and activities such as voluntary engagement in valued activities | |

| Care giving communication | |

| Greater network size and More frequency of contacts | |

| Providing financial and short term instrumental support to others | |

| Being employed | |

| Supportive residential environment | |

| Spiritual factors | Being religious |

| God health locus of control | |

| high intrinsic religiosity | |

| private prayer | |

| Religious attendance | |

| Religious or spiritual involvement | |

| Health related factors | Higher perceived health status |

| Higher ADL | |

| Health promoting behaviors and self protection | |

| Active life style | |

| Better cognitive and physical function |

4. Discussion

4.1. Protective Psychosocial Factors in Community Dwelling Older Adults

4.1.1. Demographic factors

While loneliness is one of the most important risk factors of geriatric depression (17), being married and living with a partner can modify symptoms of depression effectively (5). Also, Chao et al. showed that in Chinese families the eldest son was responsible for the care of his parents, so living with a married son was the ideal situation for older parents and was associated with less symptoms of depression (18).

Li et al. and Vanonoh et al. reported that people with a higher level of education were less exposed to depression (19, 20). However this relationship may be due to the benefits of education. Education increases people’s knowledge about health and healthy life style choices, it, also provides better access to resources and helps develop better skills to cope with old age and protect against depression.

In the study of Jogerst et al. on older people in America, age was reported as a protective factor, so that with increasing age, incidence of depression was decreased (OR = 0.88, P < 0.01) (5). Conversely another study showed that among older people in Malaysia, those who were younger had better mental health (21). These controversies are difficult to explain but it must be considered that age is not just years added to life but a combination of variables that encompass many aspects of life, such as health problems, economic hardship, social networking and other considerations such as the characteristics of the community that a person lives in, his/her culture and specific cultural attitudes to aging. These considerations also change the impact of getting older on mental health. Better socioeconomic status and a higher income were also associated with less symptoms of depression (22). This has been confirmed in Brinda et al. reporting that this is also the case in low and middle income countries. It was reported that having a pension and health insurance had a negative association with depression in older adults (23).

4.1.2. Psychological Factors

Stressful life events expose older adults to more depressive symptoms. Increased life concerns and psychological tension also impose barriers to achieving a good level of mental health (24). Environmental mastery is one determinant of an individual’s perception about his/her functioning and is related to emotional wellbeing. Pearlin and Schooler defined mastery as the extent to which a person feels that he or she has control over his or her life and environment (25, 26). It also enables a person to cope more successfully with stress. Jang et al. reports that mastery has an inverse relationship with depression and indirectly, it can also decrease the effect of disability on development of depression (25). In relation to the context of health, the term “health locus of control” refers to the degree of control that an individual believes to have over his or her life. Health locus of control consists of three major dimensions: internal, chance and powerful others. Aflakseir et al. reported on the importance of an internal health locus of control in preventing depression in older people suffering from chronic disease. It means that older people who believe that they have more control over their physical health status are better able to cope with disease and are less prone to experience depression (27).

Positive life orientation is a psychological concept including being satisfied with life, having zest for life, having plans for the future, feeling needed, and seldom feeling lonely or depressed which was measured by Pitkala et al. They showed that this construct was effective in preventing depression in a longitudinal design. It was suggested that these positive feelings can motivate old people toward self care and an active lifestyle (28). Positive life orientation, considered as a cognitive self concept, is somehow close to the concept of optimism; however in optimism the components of emotion and motivation are more prominent and it is more used in areas of social relations (28). Hirsch et al. found that when confronted with family criticisms, older people who are more optimistic and have a less pessimistic outlook present less symptoms of depression (29). They also believed that encouraging old people to achieve meaningful and attainable behavioral goals and educating them with problem solving techniques helps them face their problems and remain optimistic. Also involving family members in intervention can enhance the effectiveness of such training (29). In general, having a positive view of the future can help old people cope with their problems and family challenges and prevent depression.

Emotional Intelligence refers to the important role of emotions in our environmental and social relations. Higher emotional intelligence can enable a person to use effective adaptive coping skills in the face of stressful events and protect him/her against depression (30).

Downward social comparison is another psychological concept that has a modifying role in geriatric depression; meaning that a person evaluates his/her situation as better being than that of others. According to the social comparison theory, comparing ones situation with that of others, and having a feeling of being in a better situation, is a defense mechanisms against the losses of old age (31).

4.1.3. Social Factors

Loneliness is one of the most frequent complaints made by older people. It is associated with more severe depressive symptoms and poor prognosis (32). Many older people live alone and there is a strong relationship between loneliness and depression in old age (33). Social relations, having a close confidant, higher quality of relations, larger network and more frequent contact are factors known to protect people against geriatric depression (18). As the relationship with a spouse is the first relational circle of older adults, the presence of a considerate spouse has a key role in old age mental health. Not only the physical and emotional presence of a spouse is helpful in discharging negative feelings and daily stresses, but also the quality of this relationship and a sense of belonging and even pride in having a long and strong marriage have shown to be effective in modifying the symptoms of depression (34, 35). According to the socio emotional selectivity theory, having a close relationship, especially with a spouse, has an important role in the establishing a mechanism for older adults to cope with daily stress (36). Chao et al. considers the policy of using foreign care givers for older people in Taiwan and found that having a foreign care giver was not associated with depression, but the older people who cannot communicate well with their care givers were more prone to depressive symptoms (22). In later life, finding meaningful relations with others is much more important, and life satisfaction is strongly associated with social activity (33). A larger network, broader relations and greater integration to a social network are associated with less symptoms of depression (18, 37). These relations may lead to social interaction and make an older person’s life more meaningful.

Fastame et al. studied the role of residential environment in preventing depression by comparing the mental health status of older people in two different areas in Italy. Living in a supportive society with a more involved social context and having more opportunities for leisure time spent on farming, gardening, sport and social activities can prevent depression in old age (38).Community participation in the form of volunteering and engaging in non-profit community organizations have also been mentioned as protective factors (39, 40). This kind of participation depends greatly on context and the available resources, thus such activities may be limited in less developed communities. Social participation can prevent geriatric depression by enhancing social interaction as well as fostering a sense of being useful.

Another important function of a social network is provision of social support and many studies have investigated the effect of social support in psychological wellbeing and prevention of geriatric depression (18, 41-43). Despite extensive studies on social support and development of many scales to measure it, there is no unique agreement about its definition and measurement. Chao et al. measured social support in older Chinese adults using a model with the following seven components; network size, composition of social support, frequency of contact, proximity, type of support, helping others and satisfaction with the social support received. All of these components were associated with less symptoms of depression and the strongest among these was satisfaction with the social support received (18). Those older people who’d received financial, instrumental and emotional support, especially from family members, had more emotional resources for coping with stressful life events and such support can protect them against depression. For instance, in acculturation stress of Korean immigrants in US, those people who had greater social network support, showed less symptoms of depression.

4.1.4. Physical Health Related Factors

Some believe that depression in later life mainly affects those with chronic medical illness, cognitive impairment and disability (15, 44). Therefore enjoying better physical health can prevent symptoms of depression. On the other hand, behavior that promotes good health such as taking responsibility for one’s own health, a healthy diet such as consumption of more fruit and vegetables (45); self care behavior such as wearing suitable shoes, getting enough sleep and regular daily meals and an active life style are all related to less symptoms of depression (40). Chang et al. also considered “social participation” as a health promoting behavior which could be a preventive factor (40). However, as those factors were assessed mostly with cross sectional studies, the direction of these effects may have a reverse affect. It means that people who have better mental health status are more interested in their health and try to take care of themselves by adopting behavior that promotes good health. So these factors should be evaluated in longitudinal designs before a general conclusion can be inferred. Beside objective health status, a person’s sense of their health status is also important. Perceived health status is a powerful predictor for depression, which has been frequently studied (10, 31).

Disability is also one of the most important risk factors for geriatric depression (44). Turvey et al. found that the older people with better physical and cognitive functions, presented less symptoms of depression (46). The activities of daily living (ADL) index provides evaluations of physical function and was negatively related to depressive symptoms in several studies (22, 47, 48). This effect may have been aroused from a sense of autonomy and usefulness compared to disabled older people who feel themselves as dependent and less valuable.

4.1.5. Spiritual Factors

Belief in God and religion are very powerful preventive factors against depression. This effect may be due to making life meaningful and improving a person’s coping ability (49). Jogertst et al. studied the relationship between spirituality and depression in an international study and showed that this relation was not limited to a special geographical region However some studies have investigated the dimensions of religion and stated that intrinsic religious belief was more effective, not only in prevention, but also in recovery from depression (49). An intrinsic religious attitude reflects an individual’s perception of the importance of religion. People with intrinsic religious attitude make all of their decisions based on their religious beliefs and having powerful faith helps people cope with adverse life events. Religious attendance has also been studied as one aspect of religion and was recognized as a preventive factor in one study (49). However, in another study, general religious faith and attendance of religious service were not associated with less symptoms of depression, whereas private religious activity was (50). It means that private prayer can buffer the adverse effects of stressful life events and prevent depression.

Although the aim was to select studies with acceptable quality, this was not assessed with standard critic questionnaires. Both longitudinal and cross sectional studies were considered and factors derived from both designs were placed in the same category. As in a cross sectional design, the cause and effect relationship cannot be studied well, some of the derived factors needed to be studied more. As the study search was done as a part of a bigger study on risk factors of depression, we did not use the word “protective” in our key word search and some studies about protective factors may have been overlooked. Anyway, as the present study is not a systematic review, results of this narrative review just portray an overall picture of the existing identified protective factors of geriatric depression and present researchers with some ideas for further study on controversial areas.

4.2. Conclusions

Depression is a bio-psychosocial disorder and so there is a wide spectrum of psychosocial factors that affect it (51). Using the results of this study, it seems that intervening on some modifiable aspects of psychosocial factors can reduce depression in later life. Many biological risk factors of depression such as genetics are not modifiable, however general health status, especially perceived health status, can be modified. Education for a healthy life style such as having physical activity and a healthy diet, can not only decrease the risk of vascular depression, but it can also make people feel better about their general health. Also educating self-care to all age groups especially in middle aged and older people, can prevent some adverse health consequences. However, depression can be prevented by giving counseling to patients with a recent diagnosis of chronic disease.

Maintaining social relations is a very important factor for protection against geriatric depression. Engaging older adults in social activities to promote their relations, especially family relations, as well as participation in voluntary activities and charity organizations can be effective. Developing social clubs and making them more available for older adults is another useful preventive strategy worth mentioning.

Changing people’s perspective of life may be challenging. Positive life orientation is a characteristic that develops through the whole course of life but there are some techniques such as training in decision making and problem solving that may help individuals to feel more effective and in control of their lives. These abilities empower older people with chronic diseases and help them be safeguard against depression (15).

Many protective factors have been studied by cross sectional designs and these designs have some limitations such as failure to determine cause and effect in relations, further investigation that includes longitudinal study is necessary to clarify factors that protect against depression in later life.