1. Background

According to the fifth edition of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5), binge eating disorder (BED) is characterized by periods of uncontrollable binge eating (on average, at least once a week for three months without regular use of disproportionate weight control compensatory behaviors) and severe feelings of embarrassment and distress afterward (1). The data from the World Health Organization (WHO) collected from 14 countries show that the lifetime prevalence of this disorder for men is 2%, while it is 3% for women. Moreover, approximately 4% of men and 5% of women experience some form of binge eating symptoms during their lifetime (2). Binge eating symptoms are so prevalent that many people who struggle with the symptoms have never been diagnosed with the BED (3). In Iran, many people suffer from symptoms of eating disorders, especially binge eating (4). In a study of students in Shiraz, the prevalence of BED was reported to be 0.3% (5). Binge eating is a general health problem associated with decreased physical health (ie, being overweight and obese) and mental health (2). Despite increasing research on binge eating, scientific studies have not yet been conducted on the underlying factors of these behaviors to better understand and solve this problematic behavior. Additionally, the underlying emotional mechanisms of these behaviors, as well as the differences in these mechanisms between men and women, still need to be explored.

Some theories consider binge eating episodes to be the result of negative emotions, where these episodes act as a strategy to distract from or avoid negative emotions, such as shame, sadness, and guilt. However, as a result, negative emotions increase, and a vicious cycle is formed.

Shame is one of the negative emotions that can cause and trigger binge eating episodes. A source of shame is the body and body-image of the individual. Body-image shame involves perceptions based on which a person is negatively judged and evaluated by himself/herself and others because of his/her physical appearance (6, 7). According to Gilbert's psycho-socio-evolutionary model, the ability to have a positive impact on others and to be noticed by a social group is one of the most important factors in feeling safe, and thus, people want to leave a good image of themselves in the eyes of others. Failure in these areas is considered very threatening, and it provides a basis for activating shame and negative and critical feelings (8). Body-image appears as a central dimension in shame experience due to the importance attributed to physical appearance in modern Western societies, especially due to the globalization of social messages that attribute certain desirable psychological characteristics (eg, power, success, and happiness) to those who are fit. These early shame experiences can be recorded in memory as the center of identity and the life story of a person, and they can play an important role in social interactions as a key component for a person’s perception of himself/herself and his/her expectations (9). Body-image shame can be internal or external. External body-image shame measures perceptions in which a person is negatively judged by others for their physical appearance (eg, I feel uncomfortable in social situations because I feel that people may criticize me for my body shape). Internal body-image shame measures negative self-assessments of one’s physical appearance (eg, my physical appearance makes me feel inferior to others). Feelings of shame, and especially body-image shame (6), play an important role in the development of symptoms of eating disorders in the future, and they are associated with the symptoms of binge eating in people with the BED (10, 11). In a clinical study of women with the BED, shame also affected the severity of the binge eating symptoms (7). Shame is significantly associated with symptoms of eating disorders in non-clinical samples (12, 13) and clinical samples with eating disorders (7, 10, 14, 15). Moreover, shame can play a mediating role in childhood abuse and eating problems (15, 16).

According to some previous research, self-criticism is a variable that is closely related to shame, and it can play a mediating role in the relationship between body-image shame and eating problems. Self-criticism has been conceptualized as a punitive and violent method concerning “self to self”, especially in the face of defects or when things go wrong (17). Although self-criticism can be rooted in the desire for self-improvement and self-correction, it usually backfires because it emphasizes the flaws and feelings of inferiority (17, 18). Self-criticism has two forms with distinct functions, ie, (1) inadequate-self characterized by feelings of inferiority and inadequacy, and (2) hated-self, where self-punishment and hatred are determined by one’s feelings. In contrast to self-criticism, individuals also have the capacity for reassured-self (17). According to Gilbert et al. (17), self-criticism is an ineffective defense strategy associated with pathogenic effects. In other words, this form of self-criticism increases negative emotions and feelings of inferiority and deficiency (19). In particular, self-criticism is considered as an important variable in body and eating-related problems (20). In a study on a non-clinical sample of women in the community and a clinical sample of female patients with BED, self-criticism significantly mediated the relationship between shame and the perception of inferiority and BED (20). In women with the BED, self-criticism played an important role in predicting the symptoms of binge eating (14). In a study on non-clinical females, the type of hatred or self-criticism mediated the relationship between body-image shame and binge eating symptoms (10). In another study, both forms of self-criticism were able to mediate the relationship between self-defined memories of body-image shame and symptoms of binge eating, while only the inadequate-self form was able to mediate this relationship in men (21). Accordingly, self-criticism can be considered as an incompatible defense strategy derived from shame (18, 22), and its purpose is to correct personal characteristics or behaviors to protect oneself (18), which can be accompanied by binge eating symptoms.

A review of past research shows that self-criticism is associated with body-image shame and binge eating symptoms, and it can play a mediating role in the relationship between the two. On the other hand, little research has been performed on the differences between men and women in the forms of self-criticism and their role in mediating eating problems. Moreover, no research has yet examined the mediating role of the two forms of self-criticism and self-reassurance, and their differences between the two genders. Cultural context can also play an important role in this regard, which has not been studied in Iran as a country with an almost collectivist culture and a social structure different from those of Western and Eastern societies.

2. Objectives

This study was conducted to investigate the relationship between external and internal body-image shame and binge eating symptoms mediated by forms of self-criticism and reassured-self in Iranian men and women.

3. Methods

This correlative study was conducted based on structural equation modeling (SEM). The statistical population of the study included all undergraduate, graduate, and PhD students of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Given that the sample size above 200 (23) is recommended for modeling good structural equations and considering three to five samples per parameter (24), 313 participants were selected from September 2019 to April 2020 using the multi-stage cluster random sampling method.

3.1. Research Tools

3.1.1. Body-Image Shame Scale

This 14-item scale was developed in 2015 (6) to assess body-image shame. The BISS is composed of two subscales, including external body-image shame and internal body-image shame. Participants are asked to rate each item according to the frequency they experience body-image shame using a 5-point Likert scale (the scores range from 0 = Never to 4 = Almost always). It has been shown that BISS has perfect construct and discriminant validity, temporal stability (with an estimate of 0.75 in 4-week intervals), and high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.96 (6). In a study in Iran, the two-factor structure of BISS had a good fit, and internal consistency for the total score, internal body-image shame, and external body-image shame were 0.85, 0.79, and 0.82, respectively (25). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.93.

3.1.2. Forms of Self-criticizing/Self-reassuring Scale

This scale was developed by Gilbert and Clarke (17). The FSCRS is a 22-item self-report instrument, assessing how respondents typically think and react when they face setbacks or failures. It assesses two forms of self-criticism, ie, inadequate-self and hated-self. The third subscale is reassured-self. In the original study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.90 for inadequate-self, and 0.86 for both hated-self and reassured-self subscales (17). The Portuguese version also reported good internal consistency (0.62 ≤ α ≤ 0.89) (26). In Iran, the internal consistency for this scale based on Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85, and the test-retest reliability was 0.71 (27). In Iran, internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha calculation was 0.85, and retest reliability was 0.71 (27). For the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. In this study, only the self-criticizing scale was employed.

3.1.3. Binge Eating Scale

This scale was developed by Gormally and Black (28). BES is a 16-item self-report instrument, assessing behavioral, emotional, and cognitive dimensions of binge eating. Each item includes three to four statements that represent a rating of severity, which ranges from 0 (no difficulties with binge eating) to 3 (severe problems with binge eating). The total score ranges from 0 to 46. The scale presented good psychometric properties, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.85 in the original validation study (28). In Iran, the scale’s reliability was reported to be 0.72 using the test-retest method, 0.67 using the split-half method, and 0.85 using Cronbach’s alpha method (29). For this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.87.

3.2. Research Procedure

In this study, using the lottery method, three faculties of medicine, pharmacy, and nursing of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, were randomly selected. Then, five classes were randomly selected from each of the selected faculties. The students were asked to complete the questionnaires if they wished to participate in the study. Before completing the tools, full explanations were given to the participants, both orally and written (by attaching an instruction along with the questionnaires), and the importance of the study in examining the symptoms of overeating and identifying the factors related to them was discussed. Being a student at least at the undergraduate level, not using psychiatric drugs, and willingness to participate in the research were the inclusion criteria of research. Individuals unwilling to complete all research tools were excluded from the study. To meet the ethical considerations, the research objectives were explained to the participants before completing the questionnaires. Moreover, the participants were assured that the collected information would be analyzed in groups to preserve their confidentiality.

3.3. Data Analysis

The obtained data were analyzed based on Pearson’s correlation test and the path analysis of structural equations using SPSS 24 and Liserl-8 software. To determine the significance of the relationship between the bootstrap tests in the macro program, the Preacher and Hayes test in SPSS-24 was also performed. Bootstrap is the most powerful and logical way to determine indirect effects (30). It should be noted that 17 questionnaires were discarded due to incomplete answers; hence, the final data analysis was performed on 313 participants.

4. Results

We included a total of 313 students with an age range of 18 - 40 years and a mean age of 27.64 ± 3.87 years. The mean body mass index (BMI) of the participants was 23.32 ± 3.49. Among the participants, 159 (50.8%) were men, and 154 (49.2%) were women. The age range of men was 18 - 36 years with a mean age of 27.01 ± 3.73 years, while the age range of women was 18 - 40 years with a mean age of 23.35 ± 4.49 years. The mean BMI of the participants was 23.35 ± 3.49 (23.89 ± 3.61 in men and 22.54 ± 3.22 in women). Regarding the educational level, 208 (66.45%) participants had a bachelor’s degree, 88 (28.11%) had a master’s degree, and 17 (43.5%) had a PhD. In addition, 274 (87.54%) participants were single, and 39 (12.46%) were married.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge eating shame scale | 7.63 ± 7.36 | - | |||||

| External body-image shame | 12.06 ± 11.30 | 0.32 a | - | ||||

| Internal body-image shame | 15.34 ± 31.55 | 0.44 a | 0.71 a | - | |||

| Inadequate-self | 16.79 ± 7.83 | 0.29 a | 0.35 a | 0.43 a | - | ||

| Hated-self | 31.55 ± 15.34 | 0.35 a | 0.36 a | 0.53 a | 0.73 a | - | |

| Reassured-self | 16.79 ± 7.83 | -0.22 a | -0.22 a | -0.18* | -0.23 a | -0.34 a | - |

a P < 0.05

As can be seen in Table 1, the severity of binge eating symptoms had a positive and significant relationship with external body-image shame (r = 0.32, P = 0.001), internal body-image shame (r = 0.44, P = 0.001), inadequate-self (r = 0.29, P = 0.001), and hated-self (r = 0.35, P = 0.001), while it had a negative relationship with reassured-self (r = -0.22, P = 0.006) in men. Additionally, while external body-image shame had a positive and significant relationship with inadequate-self (r = 0.35, P = 0.001), and hated-self (r = 0.36, P = 0.001), it had a negative and significant relationship with reassured-self (r = -0.22, P = 0.006). On the other hand, internal body-image shame had a positive and significant relationship with inadequate-self (r = 0.43, P = 0.001), and hated-self (r = 0.53, P = 0.001), but it had a negative and significant relationship with reassured-self (r = -0.18, P = 0.020) in men.

| Variable | Mean ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge eating shame scale | 7.63 ± 7.36 | - | |||||

| External body-image shame | 12.06 ± 11.30 | 0.62 a | - | ||||

| Internal body-image shame | 15.34 ± 31.55 | 0.60 a | 0.84 a | - | |||

| Inadequate-self | 16.79 ± 7.83 | 0.61 a | 0.57 a | 0.64 a | - | ||

| Hated-self | 31.55 ± 15.34 | 0.56 a | 0.57 a | 0.64 a | 0.82 a | - | |

| Reassured-self | 16.79 ± 7.83 | 0.40 a | 0.43 a | 0.35 a | 0.55 a | 0.40 a | - |

a P < 0.05

According to the results presented in Table 2, the severity of binge eating symptoms had a positive and significant relationship with external body-image shame (r = 0.62, P = 0.001), internal body-image shame (r = 0.60, P = 0.001), inadequate-self (r = 0.61, P = 0.001), hated-self (r = 0.56, P = 0.001), and reassured-self (r = -0.40, P = 0.01) in women. In addition, external body-image shame had a positive and significant relationship with inadequate-self (r = 0.57, P = 0.001), hated-self (r = 0.57, P = 0.001), and reassured-self (r = 0.43, P = 0.001). On the other hand, internal body-image shame had a positive and significant relationship with inadequate-self (r = 0.64, P = 0.001), hated-self (r = 0.64, P = 0.001), and reassured-self (r = 0.35, P = 0.001) in women.

In this study, the relationship between the severity of binge eating symptoms and external and internal body-image shame mediated by self-criticism was investigated. Initially, the assumptions for modeling the structural equations were observed, which included the level of data for all the variables, normality of the data, absence of skewed data, linearity, and the absence of multiple alignments. For fitting the proposed models, the ratio of chi-square to the degree of freedom should be less than 3. Values less than 0.10 have also been suggested for the root mean square error index (RMSEA). For comparative fit (CFI), good fit (GFI), and normalized fit (NFI) indices, values of 0.90 to 1 confirm the fitness of the model (24, 31).

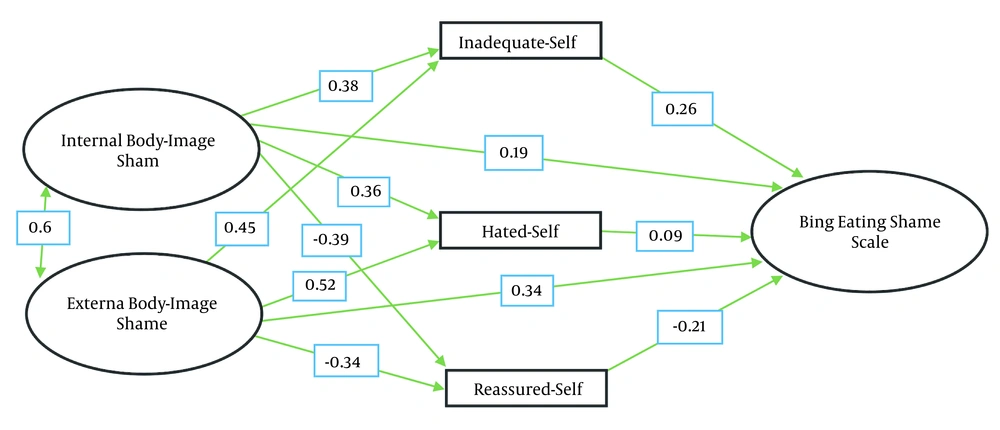

4.1. Mediator Model in Men

The results of the fit indices in Table 3 showed that the mediating model in men had a good fit. As shown in Figure 1, the direct impact coefficients on the severity of binge eating symptoms were (t = 3.61, β = 0.34) for external body-image shame, (t = 2.72, β = 0.19) for internal body-image shame, (t = 3.37, β = 0.26) for inadequate-self, (t = 1.03, β = 0.09) for hated-self, and (t = 2.93, β = 0.21) for reassured-self. Since the path coefficient (ie, the t value in the structural model) was greater than 1.96, the relationship between the two structures was significant. Thus, while the standard coefficient for the direct effects of external and internal body-image shame, inadequate-self, and reassured-self on the binge eating symptoms was significant, the coefficient of the direct effect of hated-self was not significant.

| Measure | RMSEA | NNFI | NFI | GFI | RFI | IFI | CFI | χ2/df | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value for men | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 2.93 | 4837.67 |

As shown in Table 4, the path of external body-image shame with mediated inadequate-self and reassured-self was significant with standard coefficients of 0.12 and 0.07 at the level of 0.05, respectively. The path of external body-image shame mediated by inadequate-self and reassured-self was significant with standard coefficients of 0.10 and 0.08 at the level of 0.05, respectively.

| Independent Variable | Mediating Variables | Dependent Variable | No. of Resampling | Bootstrap Limits | Estimation Error | Effect Size | Significance Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Limit | Lower Limit | |||||||

| Internal body-image shame | ||||||||

| Inadequate-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.05 | |

| Hated-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.09 | -0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | |

| Reassured-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.05 | |

| External body-image shame | ||||||||

| Inadequate-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.24 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.05 | |

| Hated-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.11 | -0.01 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| Reassured-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.15 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | |

4.2. Mediator Model in Women

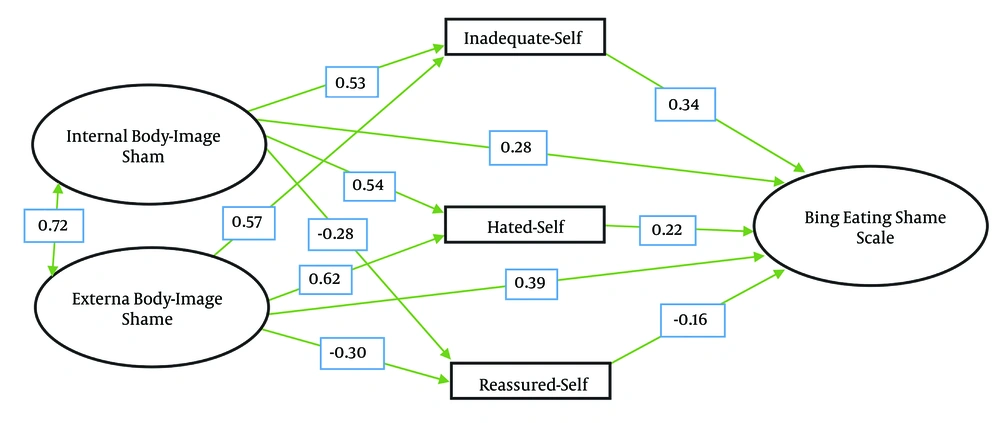

The results of fit indices in Table 5 showed that the mediating model in women had a good fit. As shown in Figure 2, the direct impact coefficients on the severity of binge eating symptoms were (t = 4.01, β = 0.39) for external body-image shame, (t = 3.45, β = 0.28) for internal body-image shame, (t = 3.59, β = 0.34) for inadequate-self, (t = 2.98, β = 0.22) for hated-self, and (t = 2.03, β = 0.16) for reassured-self. Since the path coefficient (ie, the t value in the structural model) was greater than 1.96, the relationship between the two structures was significant. Thus, the standard coefficient of direct external and internal body-image shame, inadequate-self, and reassured-self on the binge eating symptoms was significant.

| Measure | RMSEA | NNFI | NFI | GFI | RFI | IFI | CFI | χ2/df | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value for women | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 2.81 | 5043.21 |

As can be seen in Table 6, the path of external body-image shame mediated by inadequate-self, hated-self, and reassured-self was significant with standard coefficients of 0.19, 0.14, and 0.05 at the level of 0.05, respectively. The path of external body-image shame mediated by inadequate-self, hated-self, and reassured-self was significant with standard coefficients of 0.18, 0.12, and 0.05 at the level of 0.05, respectively.

| Independent Variable | Mediating Variables | Dependent Variable | No. of Resampling | Bootstrap Limits | Estimation Error | Effect Size | Significance Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper limit | Lower limit | |||||||

| Internal-body image shame | ||||||||

| Inadequate-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.05 | |

| Hated-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.05 | |

| Reassured-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| External body-image shame | ||||||||

| Inadequate-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.30 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.05 | |

| Hated-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.26 | 0.012 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.05 | |

| Reassured-self | Binge eating severity | 1000 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the association between internal and external body-image shame and binge eating symptoms in men and women mediated by self-criticism. The results showed a direct and significant relationship between internal and external body-image shame and binge eating symptoms in men and women mediated by self-criticism. This finding is consistent with previous research (7, 10, 12-15), showing that body-image shame is associated with binge eating symptoms, and that it is related to eating and weight regulation problems. However, the current study also adds new evidence to the literature by showing that in men and women, internal and external body-image shame similarly affect the symptoms of binge eating. Moreover, as expected, a positive correlation was found between body-image shame experiences and self-criticism in terms of the severity of the binge eating symptoms. In other words, the body is one of the most important sources of shame as body-image shame focuses on negative self-assessments (internal) or other people’s judgments about one’s physical appearance (external). People can resort to binge eating behaviors to cope with this body-image shame. According to Gilbert’s theory (17), the foundation of shame, especially body shame, is the early childhood experiences that have been threatening and humiliating for the “self”. These threats are internalized, influencing a person’s self-concept, especially concerning body-image. Therefore, binge eating behaviors can be an emotional regulation strategy to reduce these feelings and the negative self-image of one’s body.

The results also showed that forms of self-criticism/reassured-self can mediate the relationship between internal and external body-image shame and binge eating symptoms in men and women These results agree with those of Duarte, Pinto-Gouveia, and Ferreira (10), Pinto-Gouveia, Ferreira, and Duarte (20), and Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia (21), who showed that self-criticism mediated the relationship between body-image shame and binge eating symptoms and eating problems. Early negative experiences related to body-image and the resulting shame forms a sense of defect or imperfection in people because the physical appearance is one of the important factors of attractiveness in the eyes of others. According to the psycho-social-evolutionary model, no matter how different a person’s appearance and body are from what are attractive to the social group, it can be associated with the formation of feelings of shame and subsequent self-criticism (8). When a person is harassed or being bullied and rejected from the social group due to his/her physical appearance, these experiences lead to the formation of shame in that person. Therefore, it can be concluded that body image is one of the important sources of shame because it represents dimensions of self that can be easily evaluated and examined by others (32). People who are ashamed of their body react to this shame in different ways, one of which is that they feel inadequate and hate their body. Additionally, resorting to binge eating may also be used to regulate these difficult emotions.

In other words, unconscious self-criticism and distortion of the body-image may increase negative emotions, which is a strong predictor of episodes of binge eating and intensification of binge eating symptoms (6). Although binge eating is an ineffective strategy for controlling inner experiences, it may be effective in the short term, and it may even be associated with pleasant emotions. However, it still increases negative emotions, and at the same time, it can result in further difficulties in controlling subsequent eating behaviors. This process may be accompanied by shame and increased self-criticism, which in turn exacerbates these binge eating episodes and produces a stable self-cycle.

However, in the mediating model for the forms of self-criticism/self-assurance in the relationship between external and internal body-image shame and the severity of binge eating symptoms, there were significant gender differences in the structural relationships between the variables studied between men and women. In men, only the form of inadequate-self of self-criticism mediated the relationship between external and internal body-image shame and the severity of binge eating symptoms. This finding is consistent with those of Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia (21), who showed that the form of inadequate-self of self-criticism mediated the relationship between early experiences and shame with the symptoms of binge eating. However, in women, both forms of self-criticism (ie, inadequate-self and hated-self) mediate the relationship between body-image shame and the severity of binge eating symptoms. These results agree with those of Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia (21), and Duarte, Pinto-Gouveia, and Ferreira (10). To explain this difference in the mediating variables, it can be said that women are more vulnerable to the destructive effects of social and cultural messages that equate physical attractiveness with social attractiveness and acceptance (33). In a way, for women, the perception that one is far from the social and cultural criteria of beauty and that others see them negatively (eg, as unattractive, low, or imperfect as a social factor) may cause them to experience feelings of inadequacy, anger, self-deprecation, and hatred of their bodies, and ultimately a tendency to damage or hurt themselves.

The results of this study showed that forms of self-criticism, ie, inadequate-self and hated-self, could increase the severity of binge eating symptoms in women. This finding can be explained by considering the high socio-cultural pressures on women to display an attractive physical appearance, which can be associated with eating problems (20). Although these pressures are less prominent for men, when men also experience shame because of their physical appearance, these experiences can affect the way they relate to themselves. This may be accompanied by feelings of inadequacy and inferiority, which, in turn, affect the binge eating symptoms (21). Thus, unlike in women, the association between shame and the severity of binge eating symptoms in men due to the form of hated-self focuses less strongly on self-criticism, on feelings of inadequacy, and on certain aspects of the “self” that need to be corrected.

Alternatively, the results showed that, unlike self-criticism, reassured-self in men and women could play a mediating role, and it could be associated with a reduction in the severity of binge eating symptoms. Based on the results, it can be concluded that the more a person relates to himself/herself when faced with defects and shortcomings with kindness and reassured-self, the less likely he/she is to resort to emotion regulation and ineffective coping strategies such as binge eating.

This study had several limitations. Firstly, the current study had a cross-sectional correlation design, based on which causal results cannot be obtained. Therefore, experimental designs have to be used in future research. Secondly, this study used self-report tools to collect the required data; so social acceptance, self-report orientation, situational effects, poor recall, and errors in self-report measurement may have affected the results. Thirdly, the sample of this study was non-clinical, which limits generalizations to clinical groups. Therefore, future research can consider these limitations and examine clinical samples using objective tools in addition to self-report questionnaires. Fourthly, in this study, the subjects’ depression and its role in the mediating model were evaluated; so, it is recommended that future research examine the role of depression in the symptoms of binge eating as a disorder in emotion regulation. Finally, other variables, such as communication skills, perfectionism, and the like, may have also played a role in this research, and future research can also examine these variables.

5.1. Conclusions

The results of this study showed that forms of self-criticism could differently mediate the relationship between external and internal body-image shame and the severity of binge eating symptoms in Iranian men and women. In other words, inadequate-self in men, and inadequate-self and hated-self in women, mediated the relationship. However, self-assurance in both genders mediated the relationship between external and internal body-image shame and the severity of binge eating symptoms. Given the differences between men and women in the forms of self-criticism mediating the relationship between shame and binge eating symptoms, this finding can be considered in clinical practice, and appropriate treatment methods can be used based on the results of the current study.