1. Background

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disease affecting 100 - 150 million persons per year worldwide (1). This multifactorial disorder is affected by diverse environmental, allergic, infectious, and psychological factors. The effect of allergic, infectious, and environmental factors are well-established; nevertheless, psychological factors require further precise investigations (2). The concept of asthma control has been clearly depicted by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines encompassing 3 aspects of asthma severity, asthma education, and step-down/up pharmacological management of the disease (3). Access to appropriate treatments may lead to well-controlled asthma; however, evidence shows that most patients experience ongoing symptoms and fail to achieve ultimate control (4).

Studies have demonstrated a significant association of asthma with psychiatric mood disorders, anxiety, and depression in particular (5). These correlations are 2-sided. Uncontrolled asthma leads to an increased risk of dyspnea, wheezing, nocturnal awakening, the requirement for bronchodilator use, and poor pulmonary functioning, altogether leading to a decline in the ability to perform social/physical activities and, thus, person isolation. Therefore, asthmatic cases present an elevated rate of depression and anxiety (6). On the other hand, mood disorders, depression, and anxiety cause deterioration of symptoms, functional limitations, and more referrals to health care centers (7). Mentioned conditions negatively affect asthmatic patients’ quality of life (QOL); besides, asthma patients struggle in all moments of life, days, and nights (8, 9).

Several psychological-behavioral approaches have been proposed to treat mood disorders occurring due to underlying conditions such as asthma. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been introduced as one of the most effective approaches (10, 11), aiming to manage depression, anxiety, and asthma symptoms by relaxation, increasing awareness of anxiety and depression, determination of inefficient thoughts, cognitive reconstruction, and training how to solve problems and express skills (12).

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is one of the newest behavioral approaches, aiming to improve QOL by accepting one’s chosen values (13). Therefore, the principal goal of this approach is to increase the psychological acceptance of subjective experience of thoughts and emotions while gaining control of ineffective thoughts to reduce them and react toward them by psychological awareness at the exact moment (14). This approach is one of the subcategories of a cognitive behavioral therapy approach that has been successfully administered in different medical conditions such as diabetes mellitus (15), chronic pain (16), and rheumatoid arthritis (17), as well as psychological conditions such as suicidal thought (18), depression/anxiety (19), and interpersonal problems (20). Although this approach has not been well documented in asthma, a limited number of studies have shown promising outcomes (21, 22).

In a case-control study, Chong et al. investigated a 4-session-ACT intervention on parents whose children had asthma; in a 6-month follow-up, they found not only diminished parental anxiety but also fewer hospitalizations due to asthma exacerbation (21). Further, Aliasgari and Saghei’s study also showed positive results in this regard (22).

2. Objectives

The mechanism of ACT, including acceptance, desensitization, improving awareness, judgment-free observation, living at the moment, confrontation, and release (15, 23), as well as the promising results of the previous studies, came up with a theory about the use of this approach among asthmatic patients. In this regard, the current study is one of the first studies to assess the use of ACT in asthma to improve symptoms, mood disorders, and QOL.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Population

This randomized clinical trial study was conducted on 40 asthmatic patients referred to university-affiliated clinics from July to December 2019.

The Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (code: IR.MUI.MED.REC.1398.356). In addition, the study protocol was registered on the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (code: IRCT20200512047411N1). After explaining the study protocol to the patients, they were reassured about the confidentiality of their personal information; written consent was also obtained.

Patients aged over 18 years with a documented diagnosis of asthma (based on physical examination, spirometry, and response to the beta 2 bronchodilator test) (24) who had been on medical therapy for at least 3 months and adhered to treatments were included in the study, without any clinical records of major psychiatric disorders irrelevant to underlying asthma (ie, major mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and drug abuse). Patients’ reluctance to participate in the study and a previous history of participation in any psychological intervention for asthma control were considered as unmet criteria. Besides, the deterioration of symptoms requiring hospitalization and more than 2 sessions’ absence in the group therapy courses were exclusion criteria.

The asthma diagnosis and adherence to medications were made by a pulmonologist, and ACT was performed by a skillful psychologist in different types of cognitive-behavioral therapies.

3.2. Study Protocol

The study population was included through convenience sampling until achieving the desired number of patients. Then, spirometry was performed for all patients, and forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1) was recorded for all of them. After that, the patients were allocated to either the intervention or control group using Random Allocation Software, by which each patient was provided with a particular number that assigned him/ her to one of the groups.

At the beginning of the study, primary assessments included demographic information (age and gender), asthma-related symptoms, pulmonary function status based on FEV1, asthma control status using Asthma Control Questionnaire (ACQ), mood status using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire (HADQ), and patients’ QOL using Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ).

After that, the intervention group, besides medical treatments, attended 8 sessions of ACT with a week interval between the sessions, and the control group was medically treated only. By the end of ACT therapy, in order to assess the efficacy of this technique, the questionnaires of ACQ, HADQ, and AQLQ were refilled, and the second spirometry was performed to remeasure the pulmonary function based on FEV1.

3.3. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

The ACT course consisted of 8 sessions, each lasted for 90 minutes and performed with intervals of a week. The ACT protocol in each session was presented as follows: As there was no unified ACT approach for asthmatic patients, the current approach was designed based on the original version of ACT by Hayes and Pierson. However, some terms were altered to make a tangible concept for asthmatic patients if needed (25).

Session 1: Greeting, reviewing the basic rules, getting to know each other, introducing the mind and its products (thoughts, feelings, bodily senses, memories, and impulses), and teaching the task of recording them

Session 2: Introducing the concept of “the control is the problem,” weakening previous dysfunctional methods by using metaphors and examples, showing the inefficiencies of avoidance and controlling mental experiences, and presenting creative hopelessness

Session 3: Teaching differences between pain and suffering, increasing psychological acceptance or willingness to thoughts and feelings by metaphors (such as “the unwelcome party guest”)

Session 4: Clarification of values and goal setting applying “passengers on the bus metaphor,” providing a table of values to members, help them to identify values and set goals in the path of their values

Session 5: Defusion, teaching the concepts of fusion with mental products, providing exercises to defuse the mental products, and following goals and values

Session 6: Introducing the concept of self-conceptualization and practicing the concept of self as a context by metaphors such as Chessboard

Session 7: Introducing the concept of “Commitment” in order to participate in valuable and purposeful activities based on specified values

Session 8: Conclusion of the 7 previous sessions by introducing “psychological flexibility” and psychological pathology from the perspective of ACT, posttest implementation

3.4. Means of Assessment

3.4.1. Asthma Control Questionnaire

This questionnaire assesses 7 asthma-related items, including 5 self-administered items based on symptoms such as night awakenings, the severity of symptoms when waking up in the morning, restrictions in daily activities, shortness of breath, and wheezing while breathing; another self-administered item was based on rescue in the bronchodilator use, and 1 item was completed by the pulmonologist based on FEV1 derived from spirometry. Each of the items was scored from 0 (the best asthma control) to 6 (the worst condition) (26). The Persian version of this questionnaire has been validated with a Cronbach α of 0.89 (27).

3.4.2. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

This questionnaire contains 14 items, among which 7 items are dedicated to depression and 7 to anxiety according to symptoms in the previous week. Each question is scored from 0 to 3; therefore, each of the depression and anxiety entities scores from 0 to 21 interpreted as healthy from 0 to 7, mild from 8 to 10, moderate from 11 to 14, and severe from 15 to 21 (28, 29). The Persian version of this questionnaire has been validated with a reliability of 0.78 and validity of 0.86 (30).

3.4.3. Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

This questionnaire contains 32 questions, including 4, 5, 11, and 12 questions targeting symptoms, activity limitations, emotional functioning, and environmental exposure. Each question is scored on a scale of 1 (no impairment) to 7 (the highest level of impairment). Therefore, the higher scores indicated worse conditions (31). The Persian version of this questionnaire has been validated with a Cronbach α of 0.90 (32).

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The obtained data were entered into SPSS version 23 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill, USA). The descriptive data were presented as mean, SD, absolute numbers, and percentages. For data analysis, the independent t test, chi-square, and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were utilized. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered as a significant level.

4. Results

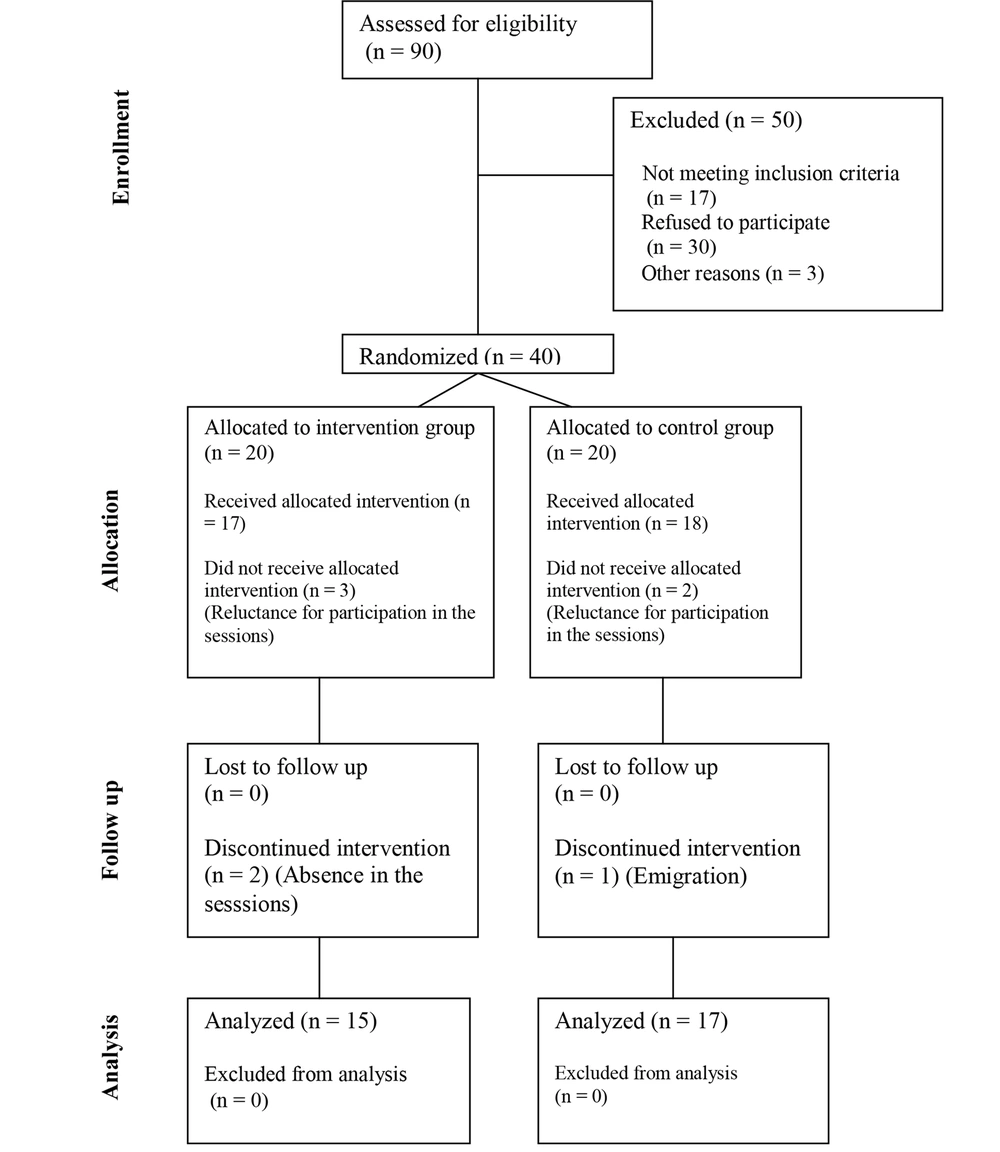

In the current study, the eligibility of 90 asthmatic patients was evaluated, among which 40 subjects met the study criteria and were divided into 2 groups, each containing 20 participants. In the intervention group, 15 patients fulfilled the protocol, and 5 patients withdrew from the study (2 patients because of reluctance to participate in the ACT sessions and 3 due to absence in more than 2 sessions of the intervention). The control group consisted of 20 participants, among which 1 and 2 patients withdrew from the study because of reluctance to participate and emigration. All of the intervention group members ended the protocol, while among the controls, 17 members completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and AQLQ, and only 10 members referred for spirometry (Figure 1).

The mean ages of cases and controls were 47.0 ± 2.59 and 47.53 ± 3.86 years (P = 0.916).

The evaluation of ACQ, HADS, and AQLQ revealed significant alterations in the ACT group (P < 0.05) by the comparison of the baseline outcomes with the findings after the intervention, while insignificant changes were detected in the control group (P > 0.05). The comparison of patients in the intervention group with those in the control group showed statistically significant higher scores of ACQ (P = 0.008), lower scores of anxiety (P = 0.002) and depression (P = 0.019) as subscales of HADS, and lower scores of AQLQ (P = 0.012) in patients under ACT. Detailed information is demonstrated in Table 1.

| Variables | Before the Intervention | After the Intervention | P Value (Time) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma Control Questionnaire | |||

| Intervention group | 16.69 ± 4.80 | 20.61 ± 3.64 | 0.002 |

| Control group | 17.25 ± 4.28 | 18.52 ± 3.74 | 0.198 |

| P value | 0.74 | 0.008 | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | |||

| Depression subscale | |||

| Intervention group | 10.38 ± 3.22 | 5.46 ± 2.02 | < 0.001 |

| Control group | 7.47 ± 3.67 | 8.21 ± 3.37 | 0.321 |

| P value | 0.031 | 0.002 | |

| Anxiety subscale | |||

| Intervention group | 12.61 ± 2.84 | 8 ± 1.95 | 0.001 |

| Control group | 11.41 ± 4.71 | 10.18 ± 3.97 | 0.256 |

| P value | 0.42 | 0.019 | |

| Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire | |||

| Symptom’s subscale | |||

| Intervention group | 49.08 ± 15.92 | 32.31 ± 15.65 | 0.002 |

| Control group | 38.08 ± 16.36 | 33.43 ± 12.88 | 0.035 |

| P value | 0.07 | 0.17 | |

| Activity limitations subscale | |||

| Intervention group | 44.99 ± 10.26 | 32.61 ± 14.97 | 0.001 |

| Control group | 42.53 ± 11.75 | 38.04 ± 11.71 | 0.004 |

| P value | 0.55 | 0.006 | |

| Emotional functioning subscale | |||

| Intervention group | 18.20 ± 6.78 | 11.58 ± 6.90 | 0.001 |

| Control group | 16.06 ± 6.31 | 15.52 ± 5.79 | 0.705 |

| P value | 0.38 | 0.029 | |

| Environmental exposure subscale | |||

| Intervention group | 22.44 ± 4.23 | 15.22 ± 6.41 | < 0.001 |

| Control group | 16.58 ± 7.02 | 17.28 ± 5.93 | 0.416 |

| P value | 0.013 | < 0.001 | |

| Total | |||

| Intervention group | 134.71 ± 32.29 | 91.74 ± 39.71 | < 0.001 |

| Control group | 113.27 ± 36.23 | 104.28 ± 32.33 | 0.051 |

| P value | 0.104 | 0.012 | |

The Comparison of Asthma Control Status, Mood Status, and Quality of Life Between the Intervention and Control Groups a

The latter evaluation of the current study targeted respiratory function assessed via spirometry, in which the 2 groups were different in FVC (Forced vital capacity), forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1, FEV1/FVC, and (forced expiratory flow) FEF 25 - 75 at baseline (P < 0.05). In the assessments after the intervention, the 2 groups were only different in FVC assessments (P = 0.019), while the other measurements revealed insignificant differences (P > 0.05; Table 2).

| Variables | Intervention Group | Control Group | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forced vital capacity | |||

| Baseline | 74.53 ± 16.58 | 105.46 ± 18.89 | < 0.001 |

| End of the study | 99.41 ± 19.11 | 93.90 ± 26.21 | 0.019 |

| FEV1 | |||

| Baseline | 66 ± 19.94 | 101.84 ± 19.66 | < 0.001 |

| End of the study | 91.75 ± 18.27 | 90.80 ± 23.70 | 0.06 |

| FEV1/FVC | |||

| Baseline | 72.14 ± 14.12 | 80.04 ± 8.54 | 0.09 |

| End of the study | 77.09 ± 9.13 | 85.45 ± 6.07 | 0.26 |

| Forced expiratory flow 25 - 75% | |||

| Baseline | 48.76 ± 16.95 | 75.30 ± 21.25 | 0.002 |

| End of the study | 66.50 ± 24.63 | 87.70 ± 36.98 | 0.66 |

The Spirometric Changes in the Study Population a

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the current report is one of the first studies to assess the impact of group ACT on diverse aspects of asthma, including control of symptoms, asthma-related mood disorders, and asthma-related QOL. The outcomes of our study revealed that the group ACT intervention could efficiently lead to improved asthma-related complications in patients suffering from this chronic disease. These findings were achieved both subjectively using questionnaires that determined symptoms control, mood status, and QOL related to asthma and objectively via spirometric evaluations.

Chong et al. (21) performed a group ACT study on parents of children with asthma in 4 sessions and, similar to the current study, utilized the primary protocols suggested by Hayes and Pierson (25), while it was modified on the basis of Hong Kong parental cultures. They used Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II), Parent Experience of Child Illness (PECI) Scale, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), Asthma Knowledge Questionnaire (AKQ), Parent Asthma Management Self-efficacy Scale (PAMSES), and Pediatric Asthma Caregiver’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (PACQL) to investigate the efficacy of their therapeutic approach. They achieved reasonable outcomes, whereas contrary to the design of our study, they believed in less than 5 sessions of group ACT for the parents who should take care of children with chronic illnesses (21). These findings are in line with other investigations conducted on parents with Asthma children as well (33-35).

Aliasgari and Saghei were the other group of researchers who performed 9 60-minute sessions of group ACT on asthmatic patients and used a QOL questionnaire to assess the effectiveness of ACT in different aspects, including physical, psychological, and environmental health, as well as social interactions, and favored this approach due to remarkable improvement in all of the mentioned entities (22).

Depression, psychological well-being, and feeling guilty were the assessed entities by Moghanloo et al. following 10 sessions of group ACT on diabetic children, an investigation that led to promising consequences among 7- to 14-year-old diabetic children (15). Naseri Saleh Abad et al. showed that group ACT in patients with breast cancer significantly improved the acceptance of the disease, which led to a remarkable decrease in cancer-related anxiety and stress (19); these findings were also supported in another study on cancer survivors (36). Consistently, similar findings were achieved in other medical conditions such as hemophilia (37), infertility (38), and fibromyalgia (39) as well.

In agreement with our findings, the literature revealed promising outcomes about the use of group ACT to manage mood disorders, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, and type of disease (40, 41). Mood disorders have a 2-sided association with asthma; therefore, we assume that symptom relief following ACT may be responsible for the improvement in the mood of the patients, or conversely, improved mood led to symptom relief in our patients. Nevertheless, regardless of the correlation between mood and symptoms, we believe that group ACT helped patients to accept asthma-related complications and, therefore, get over them.

Mindfulness and acceptance interventions in addition to routine cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) have previously been recommended because it has been demonstrated to effectively improve mental health and decrease medical symptoms along with disease-related distress. The mindfulness and acceptance approach helps patients face bothering thoughts, which have been routinely avoided. In this way, patients try not to judge the irritating condition before exposure, and eventually, these patients learn to allow the conditions to act as “they are now and here,” not more than real and not similar to previous experiences (42, 43). By developing self-regulation, worries regarding stressful conditions diminish, and patients accept conditions without any judgment, which improves the patients’ attitude of self-compassion in contrast to guilt or shame (44). The psychological disturbances are among the most prominent reasons for the asthmatic person isolation from social activities (45), a fact that deteriorates asthmatic patients’ QOL and other etiologies, including the chronic nature of the disease, irritating symptoms, feeling of being sick, being different from other members of a community, and inability to perform activities in a similar pattern to the others.

In general, our theory, along with improvement in symptoms as the primary outcome, let our patients accept their disease and its nature; therefore, they may favor attending in social activities, performing their daily life chores, and improving their adherent to medications with better insight regarding the response to the treatments, which can promote their social performances by disease control. Accordingly, patients would experience improved self-esteem and confidence, which helps them to get rid of isolation and return to social life. This condition not only rehabilitates their depressed moods (as seen in the present study) but also dramatically improves their QOL. This hypothesis has been confirmed by other studies, in which mood disorders and QOL were improved due to a significant reduction in symptom complaints, improved mood quality, and reduced hospitalization (46, 47).

Therefore, one of the strengths of this study is that it is one of the first studies to assess ACT on asthma control; this study also assessed the effects of ACT on asthma both subjectively through the self-administered questionnaires and objectively by spirometry.

Our study assessed ACT consequences on diverse aspects of asthma, including somatic symptoms, mood entities, and QOL in 4 subscales of symptoms, activity limitations, emotional functioning, and environmental exposures.

However, limitations of the current report can be attributed to the small number of the study population and requiring further investigations to follow the patients to assess the long-term efficacy of ACT on asthma rather than its short-term outcomes. In addition, a number of confounding variables could affect ACT results, such as adherence to medical therapy. Thus, to generalize the outcomes to a larger population of asthmatic patients, further evaluations with a greater number of patients with controlled analysis of the effective factors are strongly recommended.

5.1. Conclusions

We observed significant positive effects of group ACT in controlling asthma symptoms and related mood disorders, including depression and anxiety. The other valuable outcome of ACT on asthma was an improvement in QOL that may have been achieved due to ACT itself or its positive consequences on asthma symptoms and mood status. Besides, ACT favorable results were achieved not only through subjective assessments by the patients, but also through objective measurements by spirometry. Further evaluations with a longer period of intervention are strongly recommended.