1. Background

The intentional use of physical force, threatened or actual, with arms against another person or group, resulting in loss, injury, death, or psychosocial harm to an individual or individuals, which can undermine a community’s development, achievements, and prospects is called violence (1). Adolescent interpersonal violence victimization is an adverse childhood experience and a serious public health problem for youths, their families, and communities (2). Exposure to violence affects the mental health of young people and leads to their depression and anxiety (3). Economic consequences are another detrimental effect of violence (4). Perrin et al. found that 35.6% of women (95% CI 33.4 - 37.9) reported lifetime experiences of physical or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV), and 16.5% (95% CI 15.1 - 18.1) reported lifetime experience of physical or sexual non-partner violence (NPV) since the age of 15 years (5). Throughout 2000 - 2012, homicide rates were estimated to have declined by just over 16% globally (from 8.0 to 6.7 per 100000 population), and by 39% (from 6.2 to 3.8 per 100000 population) in high-income countries. Women, children, and the elderly bear the brunt of non-fatal physical, sexual, and psychological abuse. A quarter of all adults report having been physically abused as children. One in five women reports having been sexually abused as a child. One in three women has been a victim of physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner at some point in her lifetime (6). According to a 2015 report by the World Health Organization, between 2005 and 2013, the rate of violence among Iranians under the age of 18 was 81.6% (82% in men and 81.3% in women) (7).

Youth risk behavior survey data for 2019 findings revealed that 8.2% of students reported physical dating violence, 8.2% sexual dating violence, 10.8% sexual violence by anyone, of which 50% of cases were by a perpetrator other than a dating partner, 19.5% bullying on school property, and 15.7% electronic bullying victimization during the previous 12 months (2). In the school year 2017 - 18, approximately 38.5 million U.S. public school students (78%) were enrolled in a school where a violent incident occurred (8).

In a cross-sectional study by Reidy et al., a high-risk sample of boys and girls (n = 1149) aged 11 - 17 years completed surveys assessing teen dating violence (TDV) and self-defense (9). More girls reported perpetrating psychological and physical TDV, whereas twice as many boys reported sexual TDV perpetration. Girls consistently reported more fear/intimidation victimization associated with TDV (9).

Despite the magnitude of deaths resulting from violence and the massive scale on which non-fatal consequences of violence affect women, children, and the elderly, there are considerable gaps in data that undermine violence prevention efforts. A growing body of research shows that it is possible to prevent much interpersonal violence effectively and mitigate its far-reaching consequences (6). Preventing injuries to children and adolescents can reduce the burden on public health systems (4). The first step in preventing violence in schools is to identify the factors that affect student violence. To this end, it is necessary to have a questionnaire to identify the factors affecting violence prevention. In recent years, researchers have taken steps to design questionnaires related to violence, one of which is the “Measuring Attitudes and Behaviors Related to Violence and Its Impact Among Youth” Questionnaire developed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in 2005 (10). This questionnaire evaluates the components of violence prevention in four sections: Individual attitudes and beliefs, social and cognitive psychology, violence related behavior, and environmental factors (10). One of the strengths of this questionnaire is that it examines and evaluates four valuable dimensions affecting violence of school students, but it seems to have other dimensions such as family, society, education, etc., that affect the violence of school students. Therefore, the present study first sought to design a more comprehensive questionnaire, which included the dimensions of the qualitative study obtained from students’ experiences, and then assess the psychometrics of the developed questionnaire. Another questionnaire in this field, entitled Assessment of High-Risk Behaviors of Adolescents Aged 15 - 18 Years, was designed by the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) in 2018 (11). Only one part of this questionnaire raises questions about unintentional injuries and violence (11). One of the strengths of this questionnaire is that it examines the prevalence of high-risk behaviors of adolescents, including types of violence, but it does not measure the factors affecting violence in students. Another questionnaire is the School Violence Rules and Regulations Questionnaire, containing 16 questions that investigate the prevalence of violent and delinquent behavior among school students, school rules for providing confidential information to parents and the public, and school programs and activities in the field of prevention and response to violence (12). One of the strengths of this questionnaire is the examination of the frequency of violence in school students, school violence rules and regulations, school rules for providing confidential information to parents and the public, and school programs and activities in the field of prevention and response to violence, but this questionnaire does not consider the factors affecting the prevention of violence in school students. However, there are no Iranian or global research articles focusing on the design of questionnaires of the factors influencing violence prevention. This indicates the need to design a specific questionnaire on factors affecting violence prevention and examine its psychometric properties before using it.

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aimed to design and evaluate psychometric properties (the reliability and validity) of factors affecting violence prevention questionnaire in female students.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The current psychometric research was conducted in Rudsar, Iran during 2017 - 2018. This is a diagnostic accuracy aimed to design and evaluate psychometric properties (the reliability and validity) of factors affecting violence prevention questionnaire in female students. In the first part of this study (designing the questionnaire), data were collected from 50 first- and second-grade high school female students, school staff, and students’ parents by purposive sampling and using Waltz methodology (until data saturation in the qualitative study). In the second part (evaluating psychometric properties of the questionnaire), the study population was 400 first- and second-grade high school students (10 people per structure in exploratory factor analysis), included in the study by cluster sampling. Studying in school with any level of experience of violence and informed consent to participate in the study were the inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria were moving to another school and disagreement to continue participating in the study. The cluster sampling method was used in the second step of the study. At first, 8 schools (all governmental and non-governmental schools in Rudsar) whose lists were prepared through the Department of Education were selected. Then, all students from each school were selected as a statistical sample as far as possible. This research was extracted from the approved plan of the Faculty of Health of the Shahid Beheshti University of Tehran with the code of ethics IR.SBMU.PHNS.1395.95. Other ethical considerations included assuring individuals about the confidentiality of information, describing program objectives for school staff, students, and their parents, coordinating and scheduling appointments, obtaining permission to record audio and notes, and clearing audio after transcribing interviews.

3.2. Procedure

One step of the present research is a psychometric study to design factors affecting the prevention of violence questionnaire in female students using Waltz methodology, which is part of a larger combined study (13).

This part of the research performed a qualitative study using the content analysis approach. In the first step, participants received semi-structured interviews, for which a general guide or review list was prepared. Based on the provided list, the general axes of the interview were determined in advance, and other questions were asked during the interview if necessary. The interviews were conducted and recorded with the permission of the study participants. At this stage, the information was implemented, categorized, and arranged after each interview, and then the title, objectives, and research questions were edited and reviewed if necessary, followed by conducting data analysis (coding and continuous comparison) and note-taking. This step continued back and forth until data saturation, which indicated sampling completion; otherwise, it returned to the participant selection stage and went through these steps again. Data analysis in the first step of the research was performed using the conventional qualitative analysis method. The selected method for qualitative content analysis was the Granheim and Landmann method (14).

Data analysis in the first step of the research led to the extraction of 1858 primary codes, 43 categories, 27 subcategories, 9 main categories, and 2 themes. The constructs or main categories (safe family, student-specific experiences, model peers, efficient educational organization, stimulus provoking, and safe community) of this conceptual model, extracted from the first part of the study, were considered as factors influencing the prevention of students’ violent behavior.

To determine the construct validity and perform structural equation modeling (SEM), 10 students were selected for each structure by the cluster sampling method. Thus, the list of Rudsar girls’ schools was first prepared for the first and second grades. Each school formed a cluster, and the size of each cluster was proportional to the required sample size and the total number of female high school students. Then, the required clusters and eligible students from each cluster were randomly selected. A conceptual model was extracted in the first step of the present study, using an inductive approach. The objectives of the questionnaire were determined in the second step based on the dimensions and domains of violent behavior. The third step determined the specific domains of measurable dimensions of the concept while identifying the number of items necessary for the measurement of each construct. The number of initially proposed items was 212.

In the fourth step, the theoretical definitions of each dimension (theme) were provided based on the general concepts obtained from the qualitative study to convert concepts and features into appropriate items, immediately followed by the practical definition of each dimension using objective and measurable features. Finally, an attempt was made in the inductive method to write the items in the question bank as propositions (Table 1). At the end of this step, the 212-item questionnaire entered the psychometric steps after reviewing the questionnaire by members of the research team. The answers to the questions were on the Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree (15). In this section, data were collected using the questionnaire designed by self-reporting method. In this part of the study, the questionnaire for preventing violent behavior of students was designed based on the concepts and structures of the proposed model. However, the designed questionnaire needs evaluation.

| Main Classes | Categories | Subcategories | Main Code | Item | Strongly Agree | Agree | Opinion | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insecure family | Improper parenting methods | - | Family attention to student education | Q: I feel that my family members pay enough attention to my upbringing. | |||||

| The broken family | - | Parental discrimination between children | Q: I feel like my parents differentiate between their children. |

An Example of an Articulation Process for One Theme of Violent Stimulus

3.3. Item Analysis

Item were analyzed using the Waltz method. Then, the practical definition of each dimension was presented using objective and measurable features of the same dimension.

3.4. Validity and Reliability

The Validity of questionnaire was examined using face content validity (qualitative and quantitative), construct validity, content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI). Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and intra-class correlation coefficient, and SPSS 20 software was used for data analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Findings

The average age of students was 15.99 years. 30.2% of students were in the first and the rest in the second grade of high school. The mean age of the fathers and mothers was 46.74 and 42.85, respectively, and the students’ birth rate was 1.68. The highest frequency belonged to the level of education of the father (university education (30.8%)), the level of education of the mother (diploma (33.8%)), the job of the father (free work (53.7%)), and the job of the mother (housewife (81%)).

4.2. Face and Content Validity

The questionnaire included 212 questions, which needed evaluation. Assessment of the quantitative content validity led to the removal of 4 questions. Also, the qualitative content validity assessment led to the omission of 50 questions. It is noteworthy that the General Directorate of Education of Guilan Province removed question 36 from the questionnaire. In the quantitative face validity assessment by the students, 27 items did not score the required points and were eliminated. The researcher decided to remove or integrate similar questions. The mean CVI and CVR were 0.94 and 0.88, respectively.

4.3. Construct Validity (Using Exploratory Factor Analysis and Varimax Rotation)

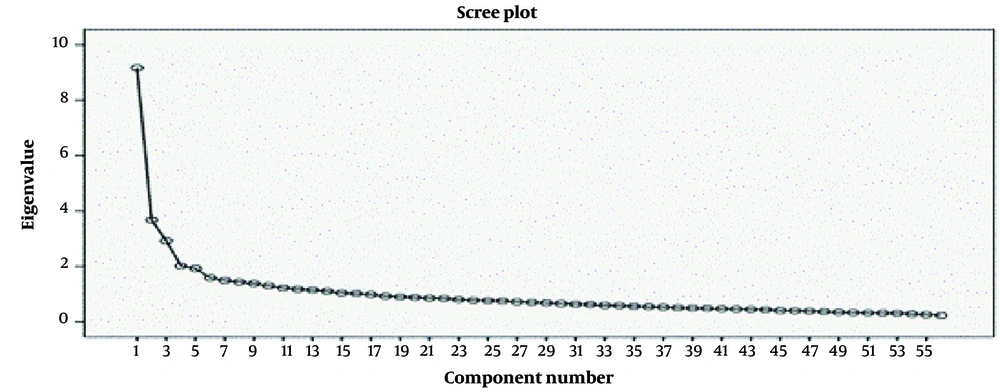

For this purpose, the data were identified as suitable for exploratory factor analysis using Kaiser’s index and Bartlett’s Test and reported in six components of the safe family (11 items), student-specific experiences (7 items), model peers (8 items), efficient educational organization (10 items), emotion-provoking (7 items), and safe community environment (5 items) using the varimax rotation for factor analysis (Table 2). For this purpose, the data were first identified as suitable for heuristic factor analysis, using Kaiser’s index (0.838) and Bartlett’s Test (χ2 = 7161.763; df = 1540; P < 0.0001), and then reported in six components of the safe family (11 items), student-specific experiences (7 items), model peers (8 items), efficient educational organization (10 items), emotion-provoking (7 items), and safe community environment (5 items) using the varimax rotation for factor analysis (Table 3). The scree plot of explaining the factor construct suggested six factors effective in preventing violence in female students (Figure 1).

| No. of Item | Items | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|

| Safe family | ||

| 1 | My mother gives me enough time. | 0.790 |

| 2 | Intimate relationships prevail in our family. | 0.787 |

| 3 | My father gives me enough time. | 0.741 |

| 4 | I am satisfied with the way my family treats me. | 0.717 |

| 5 | I am comfortable expressing problems with my parents. | 0.694 |

| 6 | My family can meet my financial needs. | 0.601 |

| 7 | My mother’s words calm me down. | 0.594 |

| 8 | My parents’ upbringing is the same. | 0.591 |

| 9 | I feel that my family members pay enough attention to my upbringing. | 0.422 |

| 10 | I feel that my parents differentiate between their children. | 0.284 |

| 11 | Most of the time, my parents overestimate the power of my friends. | 0.260 |

| Efficient educational organization | ||

| 12 | My school has taught me how to deal with violence. | 0.715 |

| 13 | I enjoy attending school. | 0.681 |

| 14 | The staff of the school give me enough time. | 0.669 |

| 15 | I accept the advice of the school staff. | 0.654 |

| 16 | The staff of the school plan recreational activities for me. | 0.637 |

| 17 | I like my school’s physical environment (such as physical space, equipment, lighting, ventilation, etc.). | 0.604 |

| 18 | Education sponsors a school violence prevention program. | 0.586 |

| 19 | As a student, I participate and help in many school affairs. | 0.586 |

| 20 | There is a school violence prevention program. | 0.582 |

| 21 | There are harsh disciplinary policies in the school. | 0.194 |

| Emotion-provoking | ||

| 22 | Sometimes I feel that there is no justice between me and others. | 0.667 |

| 23 | I feel something in my life upsets me. | 0.608 |

| 24 | Sometimes I get jealous of those around me. | 0.591 |

| 25 | I have hated a certain person in my life. | 0.567 |

| 26 | I distrust everyone. | 0.511 |

| 27 | I feel like I have no one in the world. | 0.507 |

| 28 | I became very sensitive during puberty. | 0.436 |

| Safe community | ||

| 29 | My religious beliefs are in line with most of my relatives. | 0.697 |

| 30 | I am a religious person. | 0.651 |

| 31 | My religious beliefs are in line with my family. | 0.622 |

| 32 | I avoid meeting bad friends. | 0.454 |

| 33 | My religious beliefs are in line with most of my friends. | 0.446 |

| Student-specific experiences | ||

| 34 | I always eat enough. | 0.251 |

| 35 | I like to behave like boys. | 0.242 |

| 36 | I become calmer by performing religious duties (such as praying, fasting, etc.). | 0.182 |

| 37 | I am a bully. | 0.147 |

| 38 | Sometimes I suffer from my illness. | -0.164 |

| 39 | I am very sensitive to the behavior of others. | -0.166 |

| 40 | I get bored when I have a learning problem. | -0.192 |

| Model peers | ||

| 41 | I like my friends to avoid gossiping about me. | 0.108 |

| 42 | I like my friends to avoid slandering me. | 0.143 |

| 43 | Bullying students upset me at school. | -0.173 |

| 44 | I avoid hanging out with friends who make me violent. | 0.131 |

| 45 | Compassion for a friend calms me down. | 0.733 |

| 46 | The support of my friends affects my peace of mind. | 0.729 |

| 47 | Confidentiality is very important to me. | 0.596 |

| 48 | Good friends can help solve my problems. | 0.572 |

Factor Loading of Questionnaire Items Based on Factor Analysis with Varimax Rotation (n = 400)

| Factor | Item | Number of Items | Eigenvalue | Percentage of Variance | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Safe family | 11 | 5.785 | 10.330 | 10.330 |

| 2. | Efficient educational organization | 10 | 4.247 | 7.584 | 17.914 |

| 3. | Emotion-provoking | 7 | 3.769 | 6.731 | 26.645 |

| 4. | Safe community | 5 | 2.853 | 5.294 | 29.739 |

| 5. | Model peers | 8 | 2.355 | 402.6 | 38.165 |

Eigenvalues and Percentages of Variance of Rotating Factors with Varimax Rotation of Questionnaire Structures (n = 400)

Eigenvalues and percentages of the variance of recurring factors in all variables were > 0.1, indicating the questionnaire’s appropriateness for research on factors affecting the prevention of violence by female students given the significance of all questions (Table 3). The results of exploratory factor analysis with the help of principal component analysis and varimax rotation led to the extraction of six hidden factors that explained a total of 38.165% of the variance of the violence structure in female students. Finally, 48 items met the necessary criteria concerning quantity and concepts to be included in 6 factors at this stage. In the second analysis, these 8 questions were removed due to factor loading < 0.1 and conceptual incompatibility with the factor in which they were loaded. The re-analysis of the exploratory factor was performed on 6 hidden factors using principal component analysis and varimax rotation, after which the remaining 48 items explained 38.17% of the total variance of the violence structure in female students.

4.4. Questionnaire Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha method and intra-category correlation were usedto measure the reliability of the questionnaire. Based on the results, the questionnaire has sufficient reliability (α = 0.88; ICC = 0.92) (Table 4).

| Domain | Number of Questions | Cronbach’s Alpha (n = 400) | Correlation Coefficient ICC (n = 30) | Level of Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Safe family | 11 | 0.85 | 0.91 | < 0.001 |

| Efficient educational organization | 10 | 0.82 | 0.81 | < 0.001 |

| Emotion-provoking | 7 | 0.78 | 0.93 | < 0.001 |

| Safe community | 5 | 0.71 | 0.90 | < 0.001 |

| Model peers | 8 | 0.66 | 0.73 | < 0.001 |

| Student specific experiences | 7 | 0.44 | 0.74 | < 0.001 |

| Total questions | 48 | 0.88 | 0.92 | < 0.001 |

Results of Internal Consistency Measurement (Cronbach’s Alpha) and Test-Retest Instrument (ICC)

5. Discussion

This study aimed to design and evaluate the questionnaire of factors affecting the prevention of violence by female students. According to the results, this questionnaire consisted of six main categories: Safe family, student-specific experiences, model peers, efficient educational organization, and emotion-provoking. The research data showed the safe family as one of the effective factors in preventing violence against female students. Family abnormality was one of the main factors forming the children’s personality and individual and social character (16). Hence, variables of the unsafe family would have a significant relationship with student violence (17, 18).

Intervention programs may benefit from an approach that aims to reduce exposure to violence in the family while targeting the buffering potential of teacher control and student-student relationships regarding aggression toward parents (19).

Another factor influencing the violence of female students is their specific experiences. Interviewed students stated that abnormal physical changes (such as physical and mental changes in puberty and physical changes due to physical and mental illness), unhealthy lifestyles (such as hunger and insomnia), unpleasant life events, and academic problems leading to specific experiences were effective in the violence of female students. One of the participants’ abnormal physical changes was the effect of physical and psychological changes of puberty that affected the violence of female students. The results of Cow et al. also showed a significant relationship between physical and psychological changes of puberty and the incidence of violence (20). The data also showed that one of the subclasses of abnormal physical changes was physical and mental illness. There was a link between the students’ physical and mental illness and violence. The study results by Hegarty showed that the vast majority of people with severe mental illness had been sexually and physically abused during their lifetime and often have a history of drug and sexual abuse (21). Academic problems were another factor influencing violence. The results of a study showed that students considered classroom environments and academic failure as the most important factors causing violence in school (22, 23).

Insomnia is an important predictor of suicide attempts and successful suicide. Insomnia is very common in adolescents and girls. Insomnia is associated with depression and other psychiatric disorders and an independent risk factor for suicide and substance use in adolescents, raising the possibility that treating insomnia symptoms in early adolescence may reduce the risk for these adverse outcomes (24). There is significant relationship between insomnia and the mental health of high school students (25).

Another factor influencing female students’ violence was the effect of emotion-provoking. Extrinsic feelings are a mediating variable for the phenomenon of violence. Thoughts, feelings, emotions, and behaviors interact (26). The results of Fernández-González et al., showed that the strongest predictor of dating violence perpetration with the previous level of aggression was Emotional Intelligence (27).

Lenzi et al., also examined the association of two characteristics of school climate and students’ feelings of being unsafe at school (28). Results showed that at the individual level, students perceiving higher levels of sense of community and teacher support at school were less likely to feel unsafe within the school environment. At the school level, sense of community was negatively associated with unsafe feelings (28).

The roots of aggression and violence can be found among society’s cultural components. nonviolent attitudes actualized through nonviolent models and non-punitive childrearing practices can help socialize children to become nonviolent adults (29). The data showed that the unsafe community environment is one factor affecting the incidence of violence among female students.

Violence prevention interventions that address environmental and social contexts have the potential for greater population-wide effects, yet research has been slow to identify and rigorously evaluate these types of interventions to reduce violence (30).

The data showed that an inefficient educational organization is another effective factor in causing violence. Various studies have pointed to the role of the school environment and human and non-human factors in student violence (26, 31). The violence of adults is caused and controlled by several subjective reasons mainly related to the student’s personality, family, and school (32). Also, teacher violence is the most important predictor of depression through loneliness and encourages peer victimization and the emergence of aggressive behaviors. Teachers from educational centers play a crucial role in the prevention of student violence (33).

Model peers were effective in preventing violence. Peer violence increases the risk of physical and non-physical violence (34). In a study by Oriol et al., exposure to violence exercised by support sources (teachers and classmates) explained more than 90% of the total variance in bullying behavior of students (33).

One of the limitations of this study was the decrease in the instrument external validity, mainly due to the characteristics of the sample because the findings of this study were based only on data obtained from female students in Rudsar, Iran. Other limitations of the present study included the difficulty to interact and cooperate with some education officials, the process of obtaining satisfaction from students and parents, and reducing students’ fear and anxiety to express their feelings and perceptions until reaching their trust. The results of this study can be used as a questionnaire to measure the prevention of violent behavior of female adolescents in Iran. It is suggested that practitioners and researchers take action on the validity of the questionnaire in other examples.

5.1. Conclusions

Factors extracted from factor analysis reflect the factors affecting the prevention of violence in female students, and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and intra-class correlation indicate the acceptable reliability of the questionnaire. Effective factors that can predict the risk of violence in female students include safe family, efficient educational organization, stimulus provoking, safe community, and model peers. The questionnaire can predict the risk of violence in female students.