1. Background

Today, one of the widespread social harms with ever-increasing importance is violence. Violence is the root cause of many assassinations and crimes previously learned in the community (1). In 2012, violence caused an estimated 475,000 deaths worldwide, based on which the Global Peace Index (GPI) indicated an increase in the rate of violence. The number of deaths from violence has reached its highest level in recent 25 years (2).

Investigations on high-risk behaviors among adolescents in the Qazvin province of Iran show that about 33.6% and 13.8% of adolescent boys and girls, respectively, have been beaten or physically assaulted outside the school at least once in the past year (3). Although anger is a common emotion among children and adolescents, it may lead to aggression. Many researchers in recent years have explored the importance of aggression among children and adolescents to predict their future psychosocial adjustment problems and understand the critical factors affecting the prevalence of aggressive behaviors among them (4). In this regard, some factors have been noted to be associated with aggression and violence among adolescents, such as familial issues, gender, age, media, and video games (5).

Some studies have indicated a relationship between watching violent movies and perpetrating violent behaviors, suggesting media/TV or cinema movies as the main factors contributing to violence. It has been noted that individuals, especially children and adolescents, may react to violent behaviors by characters in movies or video games by committing such behaviors, leading to more struggles and violent acts on days when they have watched such movies (6, 7). In contrast, other studies have reported no relationship between watching violent videos and committing violent behaviors, finding no evidence for the impacts of these movies on long-term violent behaviors and even, in some cases, a considerable decline in crime rates in the short term (8, 9). As both aggression and violent behavior are major public health challenges, it is critical to understand the prevalence of these behaviors and their influencing factors among adolescents.

2. Objectives

Regarding differences in the results of various studies in this field, the current research was conducted to investigate the association between watching violent scenes and the tendency to act violently among adolescents in Isfahan province (Iran).

3. Methods

This study was approved under the ethics code of IR.MUI.MED.REC.1398.022 and relied on the information retrieved from a research project (No. 188169) aiming to investigate high-risk behaviors among students in Isfahan in 2016. The data on seven types of violent behaviors were investigated and analyzed. This cross-sectional study was conducted on an adolescent population of junior and senior high school students in Isfahan province in 2016. Inclusion criteria comprised residing in the province, studying in public or private high schools (excluding schools for adults), and being in the age group of 11 to 18 years. Expressing unwillingness to participate by the adolescents or their guardians, not answering more than 10% of the questionnaire’s questions, and providing inaccurate information were regarded as exclusion criteria.

In this study, a multistage sampling method was carried out to select students, in which every city was initially considered a cluster proportionate to its size, and then an appropriate population size was assigned to each city relative to the whole province (parity sampling). After that, the ratio of urban to rural population in each city was specified, and then the sample share of each city was determined according to the number of junior and senior high schools in urban and rural regions. In the next step, a list of randomly selected schools in each city was prepared, and the total sample size assigned to each city was divided by the number of selected schools in urban or rural areas to determine the number of samples in each individual school. Finally, in each school, adolescents were randomly selected using a random number table and requested to fill out the questionnaire. The sampling design and methods used have been previously reported elsewhere in detail (10).

The sample size was calculated considering a confidence coefficient of 0.95 and an estimate of 0.50 against 2800 students. The required data were gathered using a questionnaire designed by the researchers. In order to confirm the questionnaire’s content validity, the following steps were taken: (1) extraction of relevant items by an extensive literature review; (2) verification of content validity by an expert panel consisting of social, medical practitioners, psychiatrists, public health professionals, law enforcement experts, statisticians, school health experts, and psychologists (each item was assessed using a 3-point scale with the response options of essential, useful but not essential, and not necessary); (3) calculation of the content validity ratio (CVR) for each item; and (4) removing the items failing to reach the critical level. In order to confirm the tool’s face validity, 30 adolescents were asked to evaluate the appearance of each item for any unambiguity. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to determine the reliability of the questionnaire, retrieving an alpha value of 0.80. The validity and reliability of the questionnaire have been previously affirmed (10, 11).

The final questionnaire consisted of two groups of questions. The first set of questions included queries about the demographic and social characteristics of the student's parents. The second part of the questionnaire enclosed queries related to the student’s performance regarding violence, threat level, and verbal, physical, and psychological conflicts. Ultimately, a performance score was determined based on “yes” or “no” responses, where a “yes” answer to the questions was considered a positive reply. Physical violence was defined as either perpetrating physical violence or being physically assaulted. Verbal violence was defined as either perpetrating verbal violence or being verbally assaulted. Finally, psychological violence was defined as committing threatening behaviors or feeling unsafe.

Afterward, a number of experts were chosen from each city by school health experts and trained in a one-day, 8-hour workshop on how to integrate the data obtained from 50 questionnaires. In addition, supervisors were selected to monitor the completeness of questionnaires and the quality of the data, and the data collection process after participating in a coordinated 8-hour training session. After training, the interviewers attended the selected schools and then provided the necessary details on the protocols. Then questionnaires were distributed among students to be completed. Any question or ambiguity was resolved by the interviewer. Questionnaires were then provided to the observers for quality assessment before being sent to the provincial health center. At the center, about 10% of the questionnaires were randomly re-evaluated by the central ventricle for the quality of the response.

After completing the questionnaires, the information collected was entered into SPSS 21 software. At a significance level of 0.05, appropriate tests were conducted to analyze the data. The chi-square test was used to examine differences in the frequency distribution of the independent (watching violent scenes) and dependent (violent behaviors) variables among adolescents at various levels in terms of educational level, gender, and place of residence. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between watching violent movies and violent behaviors (physical, verbal, and psychological) while adjusting for covariates (education level, gender, place of residence) to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

4. Results

This study was performed on 2800 adolescent junior and senior high school students in Isfahan province. Overall, 2727 students completed the questionnaire (a response rate of 97%). Of the participants, 50.8% were female; 38.1% were junior students, and 87.3% were urban dwellers. The mean age of the participants was 15.31 ± 1.5 years. Most of the students’ mothers were housekeepers (82%), and their fathers were employed (83.7%). Most of the parents had education levels lower than a diploma.

Regarding the relative frequency of watching violent movies among the students, the frequency of watching crime, police, and romantic movies was significantly higher among boys and village dwellers (Table 1), as well as among junior high school students compared to their senior counterparts (P = 0.001).

| Variables | Crime and Police Movies | Romantic Movies | Comedy and Family Movies | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | < 0.001 | |||

| Junior high school | 280 (29) | 165 (17.1) | 521 (53.9) | |

| Senior high school | 335 (22.4) | 208 (13.9) | 951 (63.7) | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | |||

| Female | 274 (21.4) | 73 (5.7) | 933 (72.9) | |

| Male | 341 (28.9) | 300 (25.4) | 539 (45.7) | |

| Residency | 0.04 | |||

| Urban | 521 (24.3) | 319 (14.9) | 1301 (60.8) | |

| Rural | 94 (29.5) | 54 (16.9) | 171 (53.6) |

The Frequency Distribution of Watching Violent Movie Scenes in Adolescents by the Educational Level, Gender, and Place of Residence a

Table 2 shows the overall relative frequency of various types of violent behaviors, including verbal, physical, and psychological violence, based on the educational level, gender, and place of residence. All verbal, physical, and psychological violent behaviors were significantly higher among junior students, boys, and villagers (P < 0.01).

| Violent Behaviors | P-Value b | Physical Violence | P-Value b | Verbal Violence | P-Value b | Psychological Violence | P-Value b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| Junior high school | 765 (73.6) | 553 (53.2) | 596 (57.4) | 612 (58.9) | ||||

| Senior high school | 1091 (64.6) | 711 (42.1) | 893 (52.9) | 832 (49.3) | ||||

| Gender | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||||

| Female | 849 (61.3) | 453 (32.7) | 704 (50.8) | 591 (42.6) | ||||

| Male | 1007 (75.1) | 811 (60.5) | 785 (58.5) | 853 (63.6) | ||||

| Residence | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.004 | ||||

| Urban | 1598 (67.1) | 1079 (45.3) | 1281 (53.8) | 1237 (52) | ||||

| Rural | 258 (74.6) | 185 (53.5) | 208 (60.1) | 207 (59.8) |

Violent Behaviors by Educational Level, Sex, and Place of Residence a

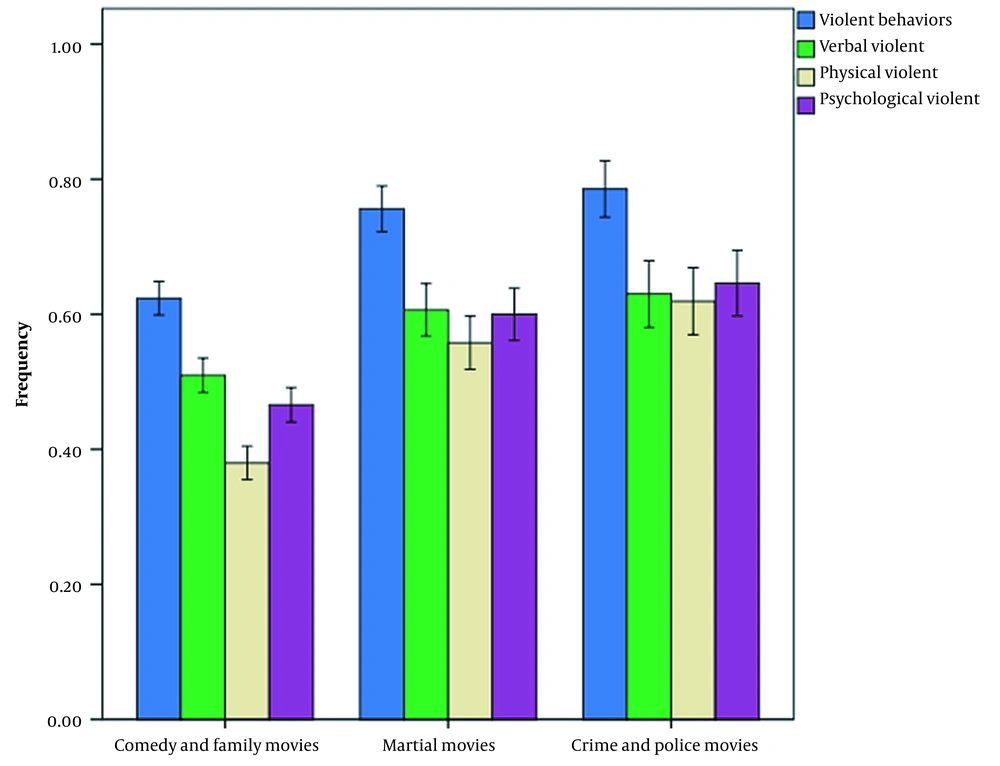

As illustrated in Figure 1, depicting the relative frequency of watching violent movies and violent behaviors among the students studied, verbal, physical, and psychological violent behaviors were significantly higher in the adolescents watching crime, police, and romantic movies than those watching comedy and family movies.

Moreover, Table 3 summarizes the results of logistic regression analysis regarding the independent association of seeing violent movies and violent behaviors (physical, verbal, and psychological) in adolescents after controlling for gender, educational level, and place of residence. Violent behaviors were significantly higher in the adolescents who watched more violent movies (adjusted OR = 1.6, CI: 1.3 - 2.1). Adjusted ORs for physical, verbal, and psychological violence were obtained as 1.6 (CI: 1.3 - 2.05), 1.3 (CI: 1.1 - 1.6), and 1.07 (CI: 0.8 - 1.3), respectively.

| Variables | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent Behavior | Physical Violence | Verbal Violence | Psychological Violence | |

| Movie genre (comedy and familial as the reference) | 1.6 (1.3 - 2.1) a | 1.6 (1.3 - 2.05) a | 1.3 (1.1 - 1.6) a | 1.07 (0.8 - 1.3) |

| Crime and police | ||||

| Romantic | 1.6 (1.2 - 2.2) a | 1.6 (1.3 - 2.1) a | 1.4 (1.1 - 1.8) a | 1.02 (0.7 - 1.3) |

| Gender (female as the reference) | 1.7 (1.4 - 2.1) a | 1.8 (2.4 - 3.4) a | 1.2 (1.1 - 1.5) a | 0.9 (0.7 - 1.1) |

| Educational level (junior high school as the reference) | 0.7 (0.6 - 0.8) a | 0.6 (0.5 - 0.8) a | 0.9 (0.7 - 1.1) | 0.9 (0.8 - 1.2) |

| Place of residence (urban as the reference) | 1.3 (1.03 - 1.7) a | 1.3 (1.04 - 1.7) a | 1.2 (0.9 - 1.6) | 1.2 (0.9 - 1.6) |

Logistic Regression Analysis for Assessing the Relationship Between Watching Violent Movies and Violent Behaviors (Physical, Verbal, and Psychological) Among Adolescents After Controlling for Education, Gender, and Place of Residence

5. Discussion

In this paper, we explored the association between watching violent movie scenes and perpetrating violent behaviors in adolescents. The results of this study confirmed that violence was a major challenge among junior and senior high school students. In the current research, watching crime-police and romantic movies was significantly correlated with violent behaviors, including physical and verbal violence in adolescents, especially among those living in rural areas, boys, and junior high school students.

We used logistic regression analysis to adjust for the effects of confounding variables, including sex, educational level, and place of residence. By eliminating these covariates, committing violent behaviors showed a significant relationship with watching movies displaying violent scenes. Committing violent behaviors was 1.8 times higher among those watching crime-police and romantic movies than individuals watching comedy and familial movies. After adjusting for the confounding variables mentioned, the likelihood of perpetrating violent behaviors while watching crime, police, or romantic movies still remained higher (1.6 times) compared to when watching comedy and familial films.

The results of our study showed that watching violent scenes was significantly associated with violent verbal and psychological behaviors. In a study investigating the understanding of students of violence in American public schools, the results showed that displaying violence in the mass media was one of the major factors influencing the tendency for violence (12). Feigelman et al. studied the environmental and psychological factors associated with youth violence among American urban residents and stated that violence in movies was directly and significantly related to violent behaviors among youth (13). In another study by Khorshidi et al., the factors affecting aggressive behaviors in junior high school students (n = 299) were investigated, demonstrating that watching violent movies was one of the main factors influencing the incidence of violence among students (14).

The results of other studies indicated a lack of association between watching violent movies and the tendency to act violently. For instance, in a study by Dahl and DellaVigna, violent movies were shown to increase violent behaviors, and regarding the relationship between watching violent movies and violent behavior, their results revealed that watching such movies could decrease violent crimes in the short term (less than three weeks). The recent study also found no evidence supporting the impact of these movies on individuals’ violent behavior in the long run (8).

Aghili et al. investigated the impact of violence in TV series on adolescents’ behavioral patterns. They assessed 150 juvenile delinquents in a behavior modification facility in the west of Tehran and witnessed no significant relationship between the rate of broadcasting and distribution of violent TV serials and movies and juvenile delinquency and the crimes committed by the subjects investigated (9). In the recent study, only delinquent adolescents were assessed, and the study population was small, which may be one of the main reasons for the differences observed between its findings and the results of the current study. Regarding violent behaviors, the role of other factors should also be taken into consideration, including exposure to stressful social events in the community and mental disorders, which can increase self-reported violence and suicide rates (15).

There are different reasons why watching violent movies can be associated with increased violence. Children watch TV three to four hours daily on average, where 60% of the movies have violent scenes, and 40% of them have exaggerated violence. Studies show that children and adolescents imitate and learn what they see in the media, which can be annexed to their behavioral reserve and further shape children’s attitudes and behaviors (16). In this regard, some measures, such as promoting life skills, including communication skills, may help reduce violent behaviors (17). Studies reveal that violence in science fiction movies can increase violence and aggression among young audiences (18). The association between media violence and violent behavior is moderated by media characteristics and social effects on the individual exposed to that content (19). Most theorists now agree that the short-term effects of watching media violence seem to be due to the immediate arousal and imitation of violent behaviors (20). In contrast, the long-term effects of watching media violence are mostly due to the observational learning of behaviors, as well as the cognition, desensitization, and activation of emotional processes (20). Obviously, not all audiences of violent films are equally affected by what they see at any given time. Studies have demonstrated that the effects of media violence on children are moderated by situational factors and personal characteristics, including the level of attention, aggressive talents of people, physical and human context characteristics, the form and content of the scene, and possibly other determinants (20).

This study has some limitations that must be considered when utilizing the results. Despite the confidentiality of the participants’ information, the accuracy and validity of the responses provided were considerable due to their self-reporting nature. Also, we had no data about the frequency and duration of exposure to violent scenes or the time limit of the types of violence studied. On the other hand, although we controlled demographic factors during regression analysis, the potential effects of unknown factors on the link between watching violent movies and violent behavior could not be ruled out. This study was conducted only among junior and senior high school students in one province of Iran, so further studies are needed to elaborate on cultural differences and their impact on students’ violent behaviors. Furthermore, it is advisable to explore this link in other age groups, including youth.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, according to the results obtained in the present study, it can be noted that watching violent movies can noticeably increase the frequency of violent behaviors among adolescents, particularly among boys and students living in rural regions.