1. Background

Suicide is one of the major health problems in the world today, playing an important role in people's well-being and mental health decline (1). Suicide refers to every act with the intention of killing oneself (2). The global incidence rate of suicide has increased. Consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) has provided and developed action plans and programs to prevent and reduce suicidal thoughts and behaviors from 2013 to 2020 (3). The suicide rate is lower in Iran than in other countries (4). However, it has increased in the country in recent decades (5). Also, suicide is the third-leading cause of death among adolescents and youths (6). Regarding the upward trend of individual, family, and social consequences of suicide, it is necessary to identify underlying factors of the phenomenon. Suicidal thoughts can be caused by various factors, including demographic status, social circumstances, family components, and psychological factors (7).

Perfectionism is one of the psychological constructs that has been extensively studied concerning suicide (8). In perfectionist people, the probability of suicidal ideation is increased. That is likely because they feel like a failure and tend to escape from such a distressing state (9). Perfectionism is a personality trait best defined as attempting to be perfect and flawless in all aspects of life (10). A new model proposed by Hewitt and Flett introduces three forms of perfectionism: Self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed. Self-oriented perfectionism includes all efforts to be a perfect person (or self), with unrealistically high performance expectations and black and white thinking, which leaves one with only two options: Total success or total failure. In this form, people are unable to accept their flaws or weaknesses. Another form is other-oriented perfectionism that makes no sense out of interpersonal relationships, expecting others to be perfect and have flawless, complete, and high standards. Finally, socially prescribed perfectionism believes that people have high standards for oneself and that confirmation from and acceptance by others depend on fulfilling these expectations, although complex and problematic (11). Both self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism have an element of criticism directed at oneself. However, other-oriented perfectionism has an element of criticism directed at others.

In recent years, many studies have been conducted to identify psychological consequences of perfectionism (12-14), such as suicide. Research has indicated that a high level of perfectionism is closely related to suicide among adolescents and adults. Indeed, perfectionism is considered a risk factor for suicidality (15). Researchers have found that perfectionist attitudes and sensitivity to criticism, as dysfunctional thoughts, have a strong relationship with suicidal ideation (16). It has also been revealed that individuals with suicidal intentions need essentially to be confirmed by other people and to act in a perfectionist manner (17).

Concerning the findings indicating a relationship between the two variables, it is necessary to investigate its mechanism. On the whole, studies show a mediating variable whose existence better explains the relationship between suicide and perfectionism (18). Empirical research has demonstrated that perfectionists tend to evaluate their behavior and performance critically and do so continually. Also, they express their concern about mistakes and negative evaluations in a self-critical manner (19).

Self-criticism is a self-critical reaction to a perceived mismatch between expected and real outcomes (inconsistency between expectation and reality). Following this mismatch, one cannot tolerate the failure to attain the standards they set for themselves (20). A self-critical person insists on achieving their goals without enjoying their achievements and judge themselves harshly. Hence, they usually feel worthless, guilty, and failure in life (21). The self-criticism process exists in all forms of perfectionism (22, 23). The relationship between perfectionism and some psychological disorders can be explained by self-criticism as a psychological construct (12). A self-critical person creates psychological conditions or states in which ruminating thoughts emerge and develop (24). It has been reported that perfectionists experience ruminating thoughts at higher levels compared to others (25). Self-criticism and its following ruminating thoughts play a role in finding solutions for interpersonal and social problems. In the sense that self-critical people, when facing interpersonal issues, feel that they are in trouble, and this feeling can increase suicide risk (26, 27). Researchers have shown that motivational and cognitive features of self-criticism result in increasing psychological distress (28). They have also claimed that self-critical people have feelings such as guilt, failure, and worthlessness and cannot enjoy their achievements (21). Accordingly, it is hypothesized that the mentioned features of self-critical people may increase the probability of suicidal ideation among them. However, a review of the research background reveals that the question "to what extent do self-critical features in perfectionists increase suicidal ideation?" has not yet been investigated. Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the direct and indirect relationships between perfectionism and suicidal ideation through mediating role of self-criticism.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between perfectionism and suicidal ideation with mediating role of self-criticism in college students.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects and Methods Sample

This descriptive correlational study was conducted on undergraduate and postgraduate students from the University of Science and Culture, Tehran, Iran, in 2018 - 2019. Given that the sample size above 200 (29) is recommended for modeling good structural equations, 300 participants were selected using the convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were willingness to participate in the study and 18 - 35 years of age. Also, all incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the study.

3.2. Data Collection Tools

3.2.1. Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS)

This 19-item scale is a self-report tool developed by Beck, Kovacs, and Weissman (1979) to examine the intensity of suicidal tendencies and thoughts. Each item is rated from 0 (low intensity) to 2 (high intensity), and the total score varies from 0 to 38. According to these items, the severity of opinions, thoughts, and tendencies for suicide is measured. The reliability and validity of this scale are confirmed in different studies. For example, Wasserman displayed high reliability (Cronbach's α = 0.89) and validity (inter-rater = 0.83) for this scale (30). In Iran, Anisi et al. estimated the reliability of this scale using Cronbach's α (= 0.95) and the split-half method (= 0.75) (31).

3.2.2. Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS)

This scale is a self-report tool developed by Hewitt and Flett (23) and standardized and validated by Besharat in Iran (32). Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) consists of three subscales: Self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism. MPS is a 30-item questionnaire in which the first ten items examine self-oriented perfectionism, the second ten items assess other-oriented perfectionism, and the last ten items evaluate socially prescribed perfectionism. The items are scored on a five-point Likert Scale from 0 to 5. Scores in each subscale range from 10 to 50. Hewitt and Flett found the internal consistency of the MPS Scale acceptable, being 0.88 for self-oriented perfectionism, 0.74 for other-oriented perfectionism, and 0.81 for socially prescribed perfectionism (33). In an Iranian sample, the Cronbach's α coefficient was estimated at 0.89 for self-oriented perfectionism, 0.83 for other-oriented perfectionism, and 0.74 for socially prescribed perfectionism, indicating high-scale homogeneity (34).

3.2.3. Self-criticism/attacking and Self-reassuring Scale (FSCRS)

The Self-criticism Scale is a 22-item questionnaire prepared from the forms of the Self-criticizing/attacking and Self-reassuring Scale (FSCRS) of Gilbert et al. (35). FSCRS consists of three subscales: Inadequate self, reassured self, and hated self (35). Response to each item is scored on a five-point Likert Scale (strongly disagree = 0 to strongly agree = 4), and acquired scores vary from 0 to 88. The Cronbach's α coefficient was computed at 0.90% for the scale (35). In an Iranian sample, the Cronbach's α coefficient was calculated to be 0.83 in total, 0.78 in men, and 0.85 in women. Also, divergent validity was examined by correlating the scale with the Rosenberg self-esteem Scale, which supported the validity of this Scale (36).

3.3. Research Procedure

Before completing the scales, the participants received a brief explanation of the purpose of the research. The scales were completed by students who met the required criteria. Concerning the ethical considerations, participation was voluntary. Also, the subjects were assured that all personal information would be anonymous, and the collected data would be analyzed in groups and kept confidential.

3.4. Data Analysis

In the descriptive section, statistical indexes were used to describe the research variables. In the inferential section, the obtained data were analyzed using the Pearson's correlation coefficient test and the path analysis using SPSS version 24 and AMOS version 21 software.

4. Results

The final analysis of the 300 students showed that 50.3% (N = 151) were female and 49.7% (N = 149) were male. Regarding marriage, 95.3% (N = 286) of the participants were single, and 4.7% (N = 14) of them were married. The age range of male students was 18 - 29 years with a mean age of 21.73 ± 2.16 years, while the age range of female students was 19 - 28 years with a mean age of 21.23 ± 1.45 years.

As shown in Table 1, suicidal thoughts had a significant positive relationship with all the variables except perfectionism (P < 0.01). Also, there was a significant positive relationship between self-criticism with self-oriented perfectionism, socially prescribed perfectionism (P < 0.01), and other-oriented perfectionism (P < 0.05). Path analysis was applied to test the designed model.

| Variables | Suicidal Ideation | Self-criticism | Self-oriented Perfectionism | Other-oriented Perfectionism | Socially Prescribed Perfectionism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal ideation | - | ||||

| Self-criticism | 0.55 a | - | |||

| Self-oriented perfectionism | 0.18 a | 0.37 a | - | ||

| Other-oriented perfectionism | 0.10 | 0.15 b | 0.48 a | - | |

| Socially prescribed perfectionism | 0.23 a | 0.38 a | 0.35 a | 0.38 a | - |

| Mean ± SD | 4.51 ± 5.09 | 37.76 ± 12.61 | 31.29 ± 6.84 | 31.09 ± 5.60 | 30.50 ± 7.05 |

a P < 0.01.

b P < 0.05.

As shown in Table 2, other-oriented perfectionism (P < 0.05, β = -0.29) had the highest significant effect on self-criticism, followed by self-oriented perfectionism (P < 0.0001, β = 0.58) and socially prescribed perfectionism (P < 0.0001, β = 0.056). According to the results in Table 2, the path coefficient of self-criticism had a significant effect on suicide (P < 0.0001, β = 0.22), while self-oriented, other-oriented, and socially prescribed perfectionism had no significant effect on suicide. The existence of mediating effect was tested under two conditions: (1) the significant general effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable and (2) the significant indirect effect or effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediating variable.

| Variables | Regression Weights | Standard Error | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Other-oriented perfectionism → Self-criticism | -0.29 | 0.136 | 0.036 |

| Self-oriented perfectionism → Self-criticism | 0.58 | 0.110 | 0.0001 |

| Socially prescribed perfectionism → Self-criticism | 0.56 | 0.101 | 0.0001 |

| Self-criticism → Suicidal ideation | 0.22 | 0.022 | 0.0001 |

| Self-oriented perfectionism → Suicidal ideation | -0.4 | 0.044 | 0.404 |

| Socially prescribed perfectionism → Suicidal ideation | 0.2 | 0.040 | 0.595 |

| Other-oriented perfectionism → Suicidal ideation | 0.3 | 0.052 | 0.615 |

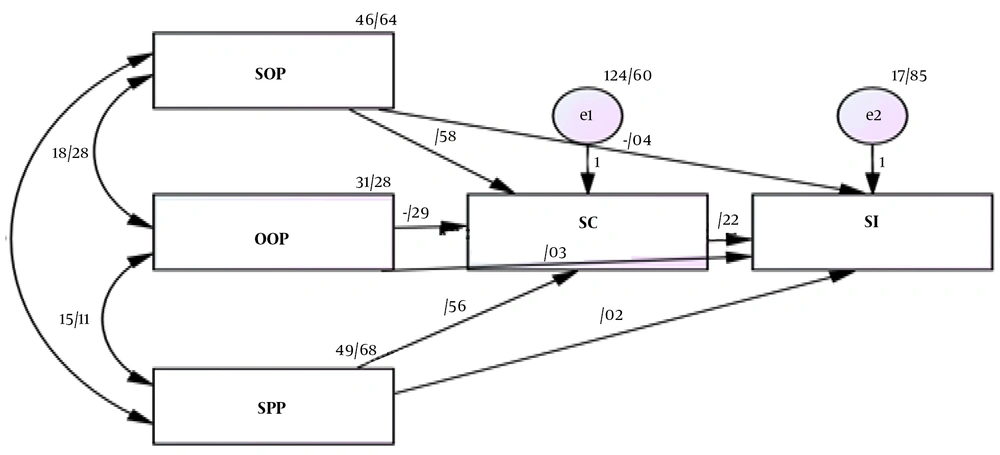

After determining the existence of mediating effect, the type of mediating effect must be examined. The results related to general, direct, and indirect effects of perfectionism components on suicide are presented in Table 3 and Figure 1.

| Effect | Standardized Rate | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall effect of socially prescribed perfectionism | 0.203 | 0.05 |

| Overall effect of self-oriented perfectionism | 0.126 | 0.064 |

| Overall effect of other-oriented perfectionism | - 0.041 | 0.576 |

| Direct effect of socially prescribed perfectionism | 0.030 | 0.485 |

| Direct effect of self-oriented perfectionism | - 0.049 | 0.290 |

| Direct effect of other-oriented perfectionism | 0.029 | 0.687 |

| Indirect effect of socially prescribed perfectionism | 0.173 | 0.004 |

| Indirect effect of self-oriented perfectionism | 0.175 | 0.005 |

| Indirect effect of other-oriented perfectionism | - 0.070 | 0.008 |

The path model showing mediating role of self-criticism in the relationship between perfectionism and suicidal ideation in university students. SOP, self-oriented perfectionism; OOP, other-oriented perfectionism; SPP, socially prescribed perfectionism; SC, self-criticism; SI, suicidal ideation.

According to the table above, general and indirect effects of socially prescribed perfectionism, but not its direct effect, were significant. Thus, there was a mediating effect with full mediation. Regarding self-oriented perfectionism, a mediating effect with full mediation was observed because its general and indirect effects, but not its direct effect, were relatively significant. Finally, other-oriented perfectionism had no mediating role. In summary, as shown in Figure 1, this model explained 30% of the suicide variance. Also, different dimensions of perfectionism predicted 21% of variations in self-criticism.

5. Discussion

The Pearson correlation coefficient results revealed a significant direct relationship between self-oriented and other-oriented perfectionism with suicidal ideation and a significant indirect relationship between the mentioned perfectionism components and suicidal ideation through mediating role of self-criticism. Moreover, a significant relationship was observed between self-criticism with perfectionism components and suicidal ideation separately.

Many empirical studies have supported the link between perfectionism and suicide (37, 38). Tendency to perfectionism causes people to pursue maladaptive thoughts and behaviors. For example, all-or-nothing thinking in perfectionists causes them to see themselves as complete failures in all life stages, leading to suicidal ideation (39). Empirical findings show that among perfectionism components, socially prescribed perfectionism is more associated with suicidal thoughts, perhaps because it leads to feelings of loneliness, isolation, and distress (17, 40, 41). Regarding this form of perfectionism, people feel pressured by society's expectations they have no control over and cannot fulfill well; consequently, they are more likely to experience feelings of loneliness, isolation, and hopelessness (42). It seems that socially prescribed perfectionists find themselves more pressured by people's expectations and opinions and are more likely than others to feel a lack of control over various aspects of their life. Therefore, they may consider suicide to escape from such societal pressures.

On the other side, findings show a significant relationship between self-criticism and suicidal thoughts. Researchers recognize the importance of the self-criticism variable in suicidal ideation (43). Self-critical people view stressful situations as absolute failure due to over-criticizing, likely increasing the risk of suicide, as confirmed in similar studies (44). Overly harsh self-criticism and self-evaluation can create feelings of guilt and worthlessness, providing ground for psychological impairments and distress.

In addition, studies show a significant relationship between perfectionism and self-criticism (45), which is in line with the results of the present study. Rezaei and Jahan found that 33% of the self-criticism variable was determined by self-oriented and other-oriented perfectionism (38). Self-oriented perfectionists seek very high standards and have unrealistic, unreasonable expectations of themselves, and since it is impossible to meet such standards and expectations, they criticize themselves. Other-oriented perfectionists also have unrealistic expectations from people, and as these high standards are not fulfilled, and they are not satisfied, they criticize themselves. By contrast, socially prescribed perfectionists direct their focus on others' standards and expectations and have no considerable personal criteria for evaluation; consequently, they are less self-critical or do self-criticism internally (46).

Abnormal perfectionists' characteristics are as follows: Fear of making mistakes, excessive, unrealistic expectations from themselves and others, fear of failure, and being hesitant. These characteristics are essentially associated with psychological disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorders, depression, and anxiety (47, 48). Perfectionists see their self-worth closely tied to their successes and achieving their goals. As perfectionists set high standards for themselves, they fail to achieve their goals and experience negative emotions (49). As discussed previously, self-criticism is a mental impairment related to self- and other-oriented perfectionism (23). It is associated with feelings of guilt, failure, worthlessness, and excessive self-blame, providing the basis for suicidal ideation. As a result, it can probably mediate the relationship between suicidal ideation and abnormal perfectionism.

Results of path analysis showed no significant relationship between other-oriented perfectionism and suicidal thoughts. Besides, the relationship was significant between self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism with suicidal ideation. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies (50, 51). Perhaps, as a result, other-oriented perfectionists strictly focus on people's shortcomings and weaknesses and attribute their problems and failures to others and sources outside of themselves (23, 52, 53).

Characteristics of other-oriented perfectionists are as follows: Excessive expectations and demands from others, impatience, exploitation, and blaming others (54). Self- and other-oriented perfectionism are related to self-relevant feelings of guilt and shame (55, 56). Self-oriented perfectionists continuously set unrealistic, high standards for themselves and focus on their weaknesses and deficiencies (57). Negative characteristics of self-oriented perfectionism include excessive self-criticism, precise and extreme programming, and over-responsibility leading to feelings of shame and guilt (58). In truth, focusing on personal losses and feelings of shame and guilt causing self-blame may lead one toward suicidal thoughts to escape from inner tensions. Socially prescribed perfectionism, compared to other perfectionism components (i.e., self-oriented and other-oriented), is more related to fear of inferiority. Indeed, observation of others' inferiority or others' experience of inferiority causes the fear of inferiority. Also, fear of failure in such people is due to fear of being judged (42, 56). Socially prescribed perfectionists are susceptible to interpret various situations in a way that leads them to feel the fear of inferiority; this can provoke a suicide crisis. Also, feeling a lack of control over behaviors and feeling trouble may lead to suicidal thoughts and behaviors (59).

Using student sampling is one of the limitations of this study. The present study was conducted on students from the University of Science and Culture in Tehran. Thus, generalizing results should be done cautiously. Accordingly, it is suggested to conduct future research randomly on other populations with different demographic characteristics. In addition, data were collected using self-report tools that increase the likelihood of error in the interpretation of results and evaluation of research. Thus, it is better to use other data collecting tools in future research, such as clinical interviews. It is also suggested to identify students at suicide risk and hold planned training courses for them to prevent suicidal attempts by modify their perfectionistic characteristics and gain knowledge about ruminations and self-critical thoughts.

5.1. Conclusions

Perfectionism is observed to have a significant association with suicidal ideation with the mediation of self-criticism. In addition to the indirect effect of the self-criticism variable, this variable directly correlates with perfectionism and suicidal ideation. Among the three components of perfectionism, self-oriented and especially socially prescribed perfectionism have a significant relationship with suicidal ideation. Perfectionism and self-criticism can predict suicidal thoughts and behavior.